Fair work schedules for the U.S. economy and society: What’s reasonable, feasible, and effective

This essay is part of Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, a compilation of 21 essays presenting innovative, evidence-based, and concrete ideas to shape the 2020 policy debate. The authors in the new book include preeminent economists, political scientists, and sociologists who use cutting-edge research methods to answer some of the thorniest economic questions facing policymakers today.

To read more about the Vision 2020 book and download the full collection of essays, click here.

Overview

Scheduling practices in low-wage jobs are the focus of increasing public concern in the United States, as awareness has grown of their potential harmful effects on workers and families. Changing work schedules requires changing the behaviors of frontline managers because they are the ones who schedule employees. Policymakers in the next Congress and administration can enact new federal laws to shift incentives on the frontlines of firms to help establish work-hour standards that benefit both employers and employees.

In this essay, I first detail the problematic scheduling practices prevalent in today’s U.S. economy and their serious ramifications for firm productivity and worker well-being. I draw on recent evidence indicating that improving work schedules can be good for families, employees, and employers alike. I then suggest two promising directions for public policy: legislating new work-hour standards in low-wage jobs and helping businesses meet them.

Problematic scheduling practices: Serious ramifications, widespread prevalence, and unproductive results

Research tells us that several dimensions of work schedules in today’s jobs—instability, unpredictability, inadequacy, and lack of input—undermine worker health and family economic security. Specifically:

- Schedule instability and unpredictability make it difficult to fulfill a host of family responsibilities, from arranging childcare and attending parent-teacher conferences to securing benefits through public safety-net programs.1

- Shortfalls in weekly work hours fuel financial insecurity and distrust in societal institutions, including Congress.2

- Problematic scheduling practices are more strongly associated with psychological distress, sleep quality, and unhappiness than are low wages.3

These problematic scheduling practices are widespread in today’s labor market, especially among low-paid workers. More than three-quarters of hourly-paid workers in the bottom third of the wage distribution report fluctuations in weekly work hours that average more than a full day of pay.4 Fully 40 percent of hourly workers say that they “know when they will need to work” one week or less in advance, and 1 in 6 know their schedule a day or less in advance.5 What’s more, between 2007 and 2015, involuntary part-time employment increased almost five times faster than voluntary part-time work and about 18 times faster than all work.6 And about half of hourly workers report that they have little or no input into the number or timing of the hours they work.7

Work scheduling problems are multidimensional problems. The most disadvantaged workers experience fluctuating, unpredictable, and scarce hours, determined by their employers. A larger proportion of black than white workers have highly fluctuating work hours at the behest of their employer, not by choice.8 And a larger proportion of low-paid than higher-paid workers, and black than white workers, experience the “triple whammy” of work-hour volatility, short advance notice, plus lack of schedule control.9

Importantly, evidence indicates that scheduling practices that are problematic for employees can also be problematic for employers. The latest research on the operations of retail firms reveals an inverted U-shaped curve between store-level labor flexibility and profit, demonstrating that too much labor flexibility undermines business goals.10 A recent randomized experiment at the U.S. retailer Gap, Inc. finds that improving schedule stability and predictability for hourly sales associates increased labor productivity and store sales, suggesting that improving scheduling practices can yield positive business benefits.11

Policy answers to problematic scheduling practices

Depending solely on employers to improve work schedules voluntarily is risky if policymakers are to improve the quality of jobs and quality of life for all U.S. workers and their families.12 The business models revered by Wall Street emphasize the importance of minimizing the cost of labor in order to maximize returns to shareholders.13 These pressures trickle down to frontline managers who are held accountable for operating within increasingly tight labor budgets.14

Frontline managers adopt practices that allow them to keep their workers’ schedules flexible so they can readily adjust staffing levels to perceived business needs. Key among managers’ labor-flexibility tools are the scheduling practices that create the problems for workers: posting schedules with little advance notice, making last-minute changes, and maintaining a large pool of workers just in case they need more.15 The incentive structures of firms make it difficult for frontline managers to change their scheduling behaviors.

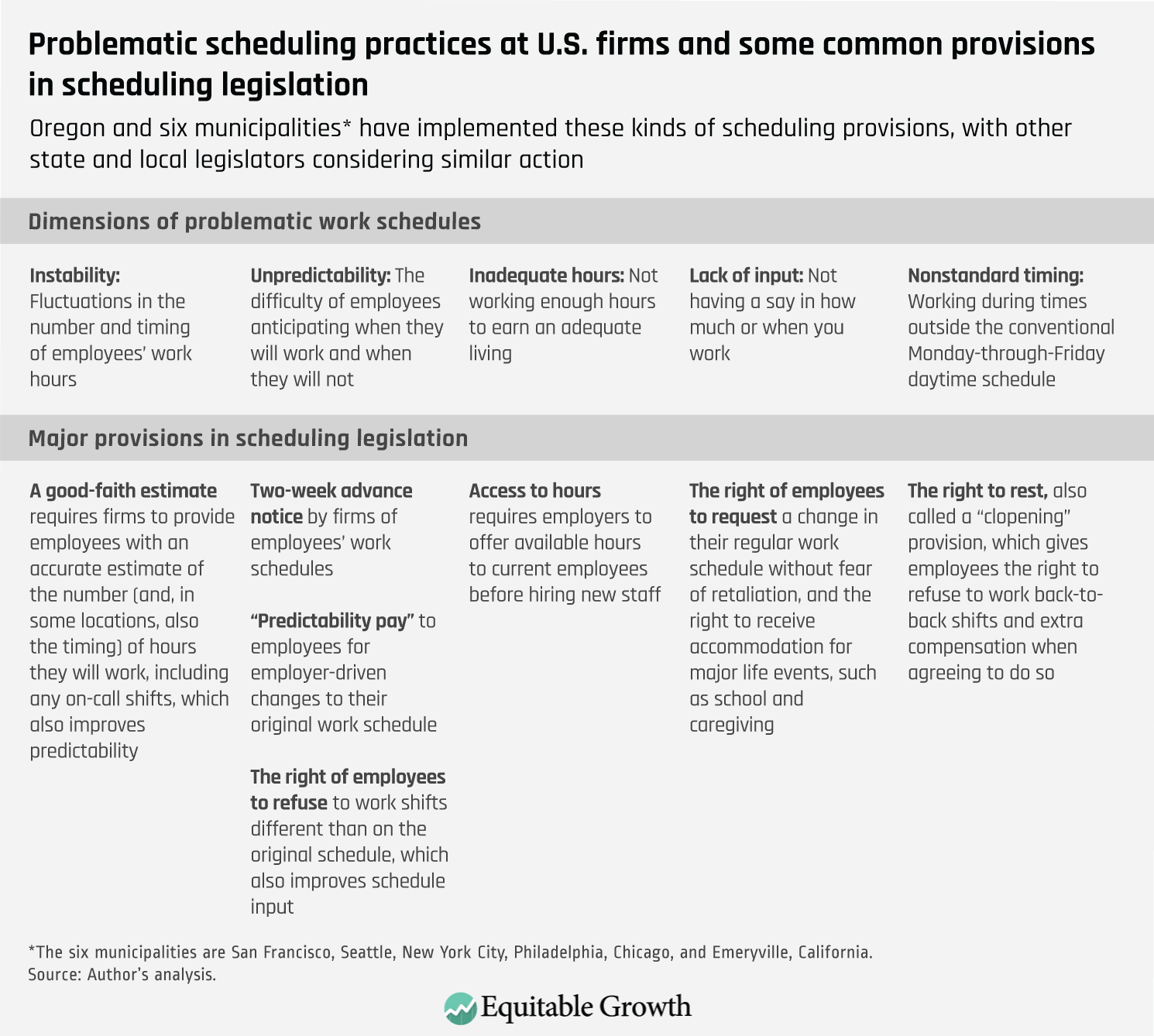

Public policy can shift incentives on the frontlines of firms. Since 2014, one state (Oregon) and six municipalities (San Francisco, Seattle, New York City, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Emeryville, California) have passed comprehensive scheduling laws, and more than a dozen additional cities have legislative initiatives underway. The new regulations are intended to establish universal standards for scheduling hourly employees in targeted industries, primarily in retail, food service, and hospitality, and in large corporations.16

Although the administrative rules vary across municipalities, these laws are coalescing around common provisions that align with the problematic dimensions of work schedules. By addressing multiple dimensions of work schedules, the laws are consistent with social science research indicating a multidimensional approach is needed to accomplish meaningful change. The major provisions included in current legislation and the scheduling dimension each one is intended to improve are compiled in Table 1.

Table 1

Scheduling legislation is designed to preserve flexibility for both employers and employees

One concern of employers is that regulating scheduling practices will impede profitability by limiting their ability to adjust labor to changing demand. But the provisions of the laws place more emphasis on improving schedule predictability rather than schedule stability. This focus on predictability preserves labor flexibility for employers. Notably, even though workers’ schedules are to be posted two weeks in advance of each workweek, these laws do not prohibit employers from making changes to the schedules once they are posted. Instead, the laws require employers to provide a premium—“predictability pay”—to workers when a manager requests a change, commonly an extra hour of pay.

Predictability pay for schedule changes is a risk-sharing approach. It acknowledges that schedule changes create costs for workers such as by disrupting childcare arrangements, school and training schedules, and transportation arrangements. Just as an overtime premium compensates hourly employees for working beyond what is conventionally viewed as a reasonable workweek, predictability pay helps to compensate employees for the adjustments they have to make when accommodating employer requests for flexibility. Predictability pay also provides an incentive to managers to limit schedule changes to those literally worth it to the business.

Of equal concern is that by increasing the cost to employers of schedule changes, scheduling legislation will reduce flexibility for employees. But the predictability premium only pertains to employer-driven schedule changes. The laws do not require that employers pay a premium when employees swap shifts with one another or actively initiate a change, including requesting additional hours or even leaving work early.

And, although it may seem logical that employers may become hesitant to grant an employee’s request for time off out of fear that they will have to provide predictability pay to another employee who works those hours, the administrative rules governing the implementation of current laws outline procedures employers can follow to respond to such employee-driven schedule changes without having to pay a predictability premium. Moreover, the “right to request” and “access to hours” provisions, along with the “right to refuse” to work hours not on the original work schedule, expand employee control over work hours.

In sum, the concern that scheduling legislation will necessarily curtail employer or employee flexibility appears overstated, as does the assumption that low-paid jobs provide substantial flexibility to begin with—more than 50 percent of low-paid hourly workers say they have little or no input into the number or timing of their work hours.17 Nonetheless, such concerns are important and are being addressed in ongoing research on the implementation and effects of current scheduling legislation, described below.

Problematic scheduling practices are often driven by factors under employers’ control

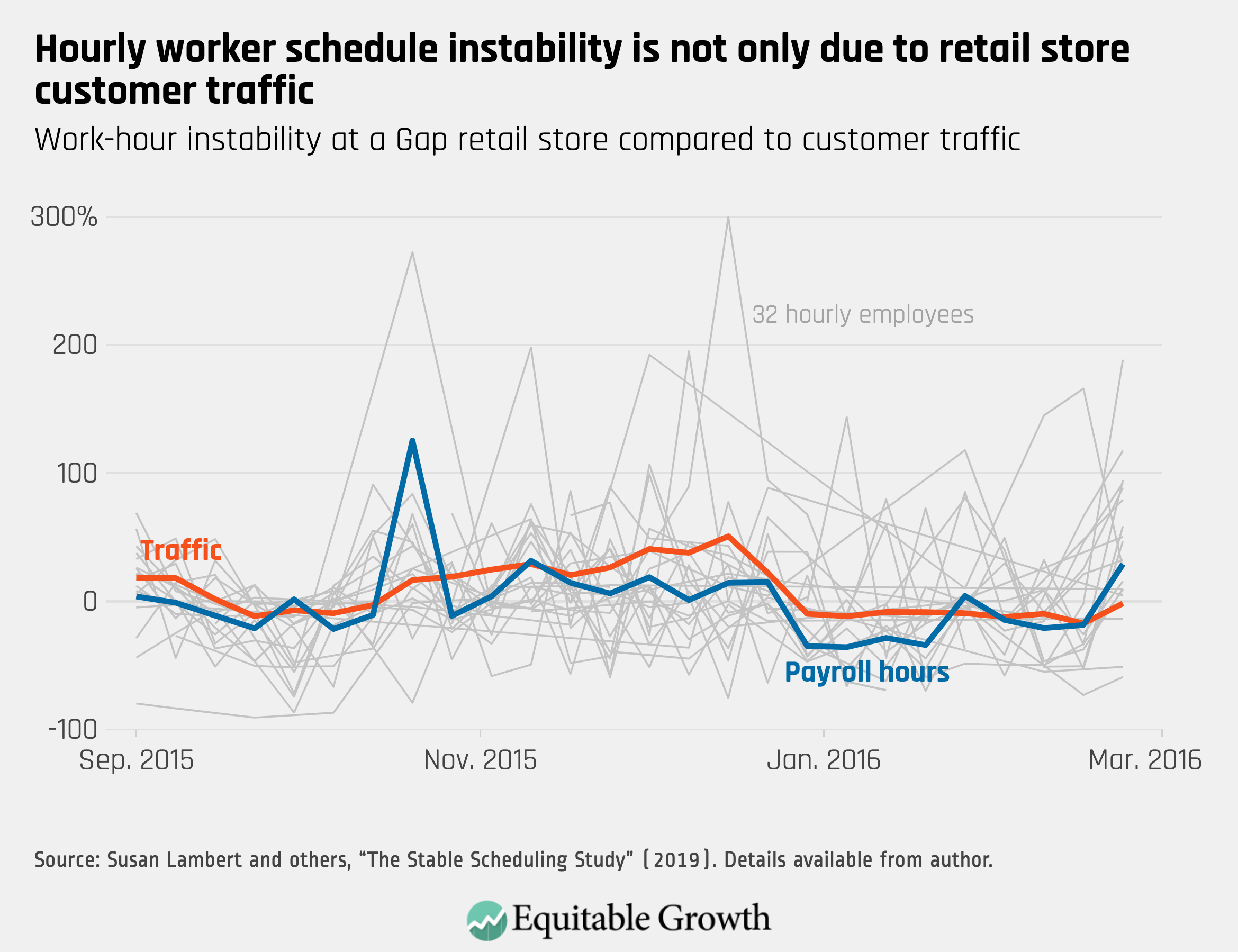

The common view is that schedule instability and unpredictability are driven by factors outside the control of employers, notably variations in consumer demand. But research indicates that much of the variation in employees’ schedules is driven by internal corporate processes, such as the accountability practices discussed above and adjustments to scheduled sales promotions and deliveries rather than by changing consumer demand.18

A telling case in point is data from one store that participated in the Gap scheduling experiment referenced above. Specifically, the data show that although there are certainly peaks and valleys in traffic and overall store labor hours, individual employees’ hours vary much more dramatically. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Each thin line represents a store employee and shows how much an individual employee’s hours diverged from his/her average hours over a six-month period. The thick blue line graphs how much the store’s overall labor hours varied from its mean over the months. And the orange line shows how much customer traffic varied. As is evident, although there are certainly peaks and valleys in traffic and overall store labor hours, individual employees’ hours vary much more dramatically. This and other evidence indicates that there is more stability and predictability already in business that can be passed on to workers by improving basic business and scheduling practices.19

Is scheduling legislation effective?

Given that scheduling legislation is new, so too is research on its effects. To date, state-of-the-art studies conducted in Seattle and Emeryville, California suggest these laws are making a difference in the lives of workers in jobs in retail and food service. By comparing survey responses of retail and food-service employees working in the same firms but in municipalities with and without scheduling legislation, sociologists Kristen Harknett and Véronique Irwin at the University of California, San Francisco and Daniel Schneider at UC Berkeley are able to isolate changes in workers’ scheduling experiences due to Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance, which became law in 2017. They find that just eight months after the new scheduling law went into effect, the share of covered employees reporting at least 14 days advance notice increased by 20 percent (more than 9 percentage points). The new law also more than doubled the reported receipt of “predictability pay” for schedule changes (a 7 percentage point increase relative to baseline).20 In the second year of the evaluation of Seattle’s scheduling ordinance, Schneider and Harknett will examine the possible effects on employee health and well-being.

In Emeryville, economist Elizabeth Ananat at Columbia University and child development expert Anna Gassman-Pines at Duke University have fielded time-diary studies with mothers of young children that enable them to track the effects of scheduling legislation on parents’ daily well-being. They find that the Emeryville Fair Workweek Ordinance decreased daily instances of schedule unpredictability overall and also reduced last-minute schedule changes. They also find an overall effect on the well-being of working parents, with the law improving subjective reports of sleep quality.21

Research conducted by myself and my colleague Anna Haley at Rutgers University on the implementation of scheduling laws by frontline managers in Seattle, New York City, and Philadelphia indicates that compliance will take time. The laws are complex, and firms and managers are still figuring out strategies of implementation.22 The full effects of the laws may not be realized for some time.

A consistent challenge for managers is complying with requirements for documentation of the scheduling process, especially documenting schedule changes. Even though most covered employers are part of large chains, not all use sophisticated software, and the manager/owners of franchises are often left to develop their own systems. The federal government could help businesses by subsidizing research and development of technology to ease compliance and documentation, facilitating enforcement too.

Is federal legislation a useful next step?

The federal-level Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 was informed by decades of prior state-level legislation demonstrating that businesses could, in fact, thrive without child labor and testing employer incentives to reduce the punishingly long work hours characteristic of the industrial revolution—what is now our overtime premium. Eight decades later, similar policy innovation at the state and local level to improve the quality of U.S. jobs in the 21st century lays a foundation for federal legislation, providing evidence of the feasibility of changing employer scheduling practices and the consequences for workers, families, and firms of doing so.23

In addition to establishing universal work-hour standards, federal legislation might also lessen implementation challenges. Both corporate representatives and software vendors express a reluctance to change their scheduling and “workforce optimization” technologies, given that administrative rules vary from one city to another.24 Perhaps most importantly, without federal legislation, there is no clear incentive for corporations to change the labor-cost accountability structures that drive these practices.

Download FileFair work schedules for the U.S. economy and society: What’s reasonable, feasible, and effective

Conclusion

Workers in low-paid hourly jobs often face a constellation of problematic scheduling conditions, among them fluctuating hours, short notice of their work schedules, too few scheduled hours, and little input into when and how much they work. Research is clear that the consequences of these conditions can be grim. Unstable, unpredictable hours over which workers have little control make it difficult to care for loved ones, do well in school, and achieve economic security.

But change is feasible. The best available evidence indicates that it is possible for employers to improve the predictability and stability of employees’ schedules while also meeting business imperatives. Currently, firms’ accountability metrics focus managers’ attention on the instability and unpredictability in business demands, leading managers to discount the substantial stability and predictability that also exists. Scheduling legislation shifts incentive structures and the focus of managers. With the right tools and assistance, managers can learn to identify and deliver greater stability and predictability to workers. The federal government has an opportunity to provide leadership in transforming problematic scheduling practices into fair scheduling standards that will support the vitality of U.S. families and firms.

—Susan Lambert is a professor at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration.

End Notes

1. Dan Clawson and Naomi Gerstel, Unequal Time: Gender, Class, and Family in Employment Schedules (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014); Anna Haley-Lock and Linn Posey-Maddox, “Fitting It All In: How Mothers’ Employment Shapes Their School Engagement,” Community, Work & Family 19 (3) (2016): 302–321; Julia R. Henly and others, “Determinants of Subsidy Stability and Child Care Continuity” (Washington: Urban Institute, 2015), available at https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/65686/2000350-Determinants-of-Subsidy-Stability-and-Child-Care-Continuity.pdf.

2. Susan J. Lambert, Julia R. Henly, and JaeSeung Kim, “Precarious Work Schedules as a Source of Economic Insecurity and Institutional Distrust,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5 (4) (2019): 218–57.

3. Daniel Schneider and Kristen Harknett, “Consequences of Routine Work-Schedule Instability for Worker Health and Well-being,” American Sociological Review 84 (1) (2019): 82–114.

4. Lambert, Henly, and Kim, “Precarious Work Schedules as a Source of Economic Insecurity and Institutional Distrust.”

5. Ibid.

6. Lonnie Golden, “Still Falling Short on Hours and Pay: Part-time Work Becoming New Normal” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2016), available at https://www.epi.org/publication/still-falling-short-on-hours-and-pay-part-time-work-becoming-new-normal/.

7. Lambert, Henly, and Kim, “Precarious Work Schedules as a Source of Economic Insecurity and Institutional Distrust”; Schneider and Harknett, “Consequences of Routine Work-Schedule Instability for Worker Health and Well-being.”

8. Susan J. Lambert and others, “The Magnitude and Meaning of Work Hour Volatility among Millennials in the U.S. Labor Market” (under review; available from author).

9. Ibid.

10. Kesavan Saravanan, Bradley R. Staats, and Wendell Gilland, “Volume Flexibility in Services: The Costs and Benefits of Flexible Labor Resources,” Management Science 60 (8) (2014): 1884–1906.

11. Joan C. Williams and others, “Stable Scheduling Increases Productivity and Sales: The Stable Scheduling Study” (2018), available at https://www.ssa.uchicago.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/2018_Stable_Schedules_Study_Report.pdf.

12. Susan J. Lambert, “The Limits of Voluntary Employer Action for Improving Low-level Jobs.” In Marion Crain and Michael Sherraden, eds., Working and Living in the Shadow of Economic Fragility (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

13. Francoise Carré and Chris Tilly, Where Bad Jobs are Better: Why Retail Jobs Differ across Countries and Companies (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2014); Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt, Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2017).

14. Carré and Tilly, Where Bad Jobs are Better: Why Retail Jobs Differ across Countries and Companies; Arne L. Kalleberg, Precarious Lives: Job Insecurity and Well-being in Rich Democracies (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2018).

15. Susan J. Lambert, “Passing the Buck: Labor Flexibility Practices that Transfer Risk onto Hourly Workers,” Human Relations 61 (9) (2008): 1203–1227.

16. In addition to jobs in retail, food service, and hospitality, the Chicago Fair Workweek Ordinance covers janitorial, maintenance, and security services, healthcare, manufacturing, warehouse services, and nonprofit organizations. Jobs must pay less than $26 per hour or $50,000 a year. The Chicago ordinance goes into effect July 1, 2020.

17. Lambert, Henly, and Kim, “Precarious Work Schedules as a Source of Economic Insecurity and Institutional Distrust.”

18. Williams and others, “Stable Scheduling Increases Productivity and Sales: The Stable Scheduling Study”; Zeynep Ton, The Good Jobs Strategy: How the Smartest Companies Invest in Employees to Lower Costs and Boost Profits (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014).

19. Marshall Fisher, Santiago Gallino, and Serguei Nestessine, “Retailers are Squandering their Most Potent Weapons,” Harvard Business Review (2019), available at https://hbr.org/2019/01/retailers-are-squandering-their-most-potent-weapons; Susan J. Lambert and Julia R. Henly, “Managers’ Strategies for Balancing Business Requirements with Employee Needs” (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2010), available at https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/voices.uchicago.edu/dist/3/1174/files/2018/06/univ_of_chicago_work_scheduling_manager_report_6_25_0-1gq8rxc.pdf; Ton, The Good Jobs Strategy: How the Smartest Companies Invest in Employees to Lower Costs and Boost Profits.

20. West Coast Poverty Center, “Evaluation of Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance: Year 1 Findings” (Seattle: University of Washington, 2019), available at https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/CityAuditor/auditreports/SSO_EvaluationYear1Report_122019.pdf

21. Elizabeth O. Ananat, Anna Gassman-Pines, and J. Fitz-Henley, “The Effects of the Emeryville, CA Fair Workweek Ordinance on the Daily Lives of Low-wage Workers and Their Families,” Paper presented at the Society for Research in Child Development Biennial Meeting, Baltimore, MD, 2019.

22. West Coast Poverty Center, “Evaluation of Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance: Year 1 Findings.”

23. The Schedules That Work Act has been introduced into Congress during three sessions: 2015–2016, 2017–2018, and 2019–2020. The lead sponsors are Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) in the Senate and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) in the House. The bill incorporates most of the provisions included in municipal-level legislation.

24. West Coast Poverty Center, “Evaluation of Seattle’s Secure Scheduling Ordinance: Baseline Report and Considerations for the Year 1 Evaluation” (Seattle: University of Washington, 2018), available at https://www.seattle.gov/Documents/Departments/CityAuditor/auditreports/SecureSchedulingReport.pdf.