COVID-19 lockdown policy in the United States: Past, present, and future trends

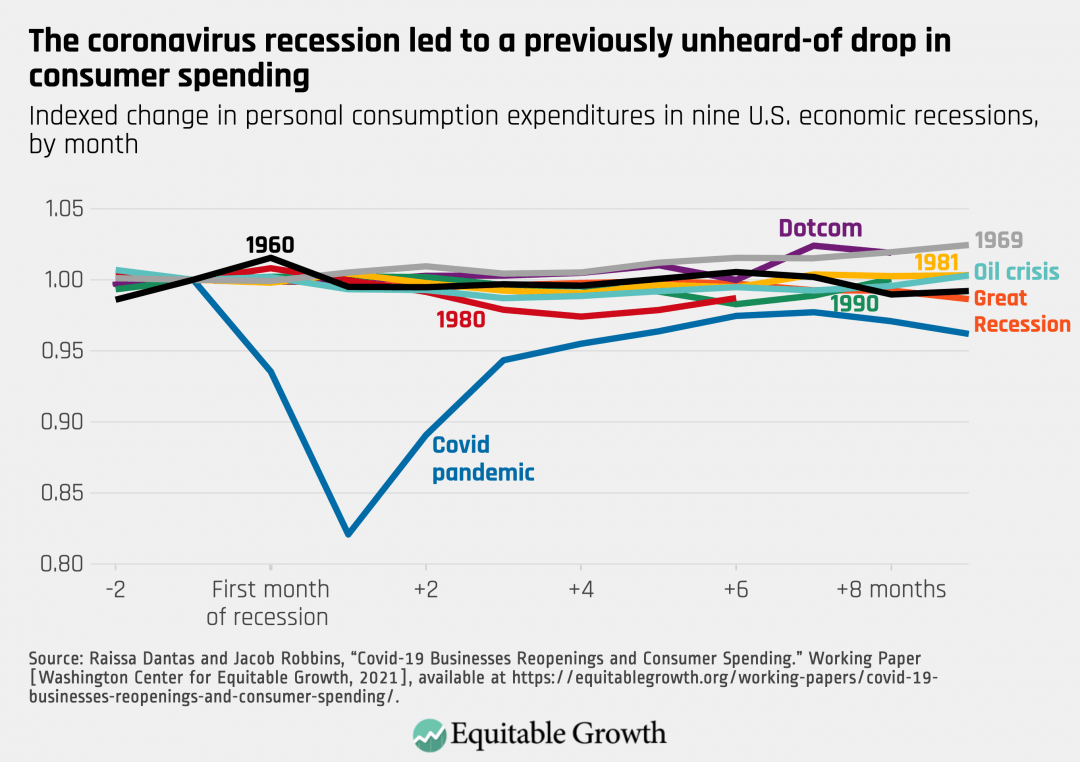

The onset of the coronavirus pandemic and the rising death toll from COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, initiated an unprecedented decline in consumer spending in the United States, dwarfing the effects of any previous recession. Understanding what is driving consumer spending—and, in particular, the effects of lockdown policies—is crucially important in designing policies for a full economic recovery, as consumption is two-thirds of Gross Domestic Product.

Yet policies that maximize GDP and employment do not maximize welfare because crowded stores and restaurants can cause widespread COVID-19 infections in customers and workers, leading to further outbreaks. As many countries and states have learned by hard experience, a premature reopening is a recipe for a dramatic rise in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. The very purpose of restrictions on retail and restaurant activity is to decrease visits, and thus spending decreases. As such, the declines in consumer spending that restrictions bring are not the costs of these policies; in fact, they are the benefits.

In our new working paper, I and my co-author, Raissa Dantas, a Ph.D. candidate in economics at the University of Illinois at Chicago, analyze the causes of the decline and rise in retail spending in the United States—a striking decline of almost 20 percent 2 months after the crisis, followed by a rapid recovery and then a transition to a slow increase. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

We find equally striking results about the interplay between fear of COVID-19 and restrictions on consumer behavior. In the early weeks of the pandemic, spending declines were driven fully by fear of catching the coronavirus, and not by restrictions on consumer behavior such as stay-at-home orders. In April and May, however, fear of COVID-19 declined while restrictions on nonessential shopping remained in place. We find the retail and restaurant spending restrictions caused substantial declines in spending for the categories directly affected by restrictions, such as nonessential in-store retail items and full-service in-restaurant dining. Even in recovery, consumption remains depressed, compared to previous recessions.

These results show that the restrictions put in place by governments had their intended effect. The restrictions successfully deterred a large majority of consumers from behavior that would have been beneficial to a superficial measure of welfare—aggregate GDP—but which would have led to the increased spread of the coronavirus and COVID-19. Two studies by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Johns Hopkins University demonstrate that allowing indoor dining is associated with a substantial rise in COVID cases and that stay-at-home orders are effective in reducing COVID-19 infections.

In our working paper, we analyze the effects of business restrictions on consumer spending using data from Earnest Research, a company that analyzes spending data from a panel of 6 million U.S. households. The data allow for a detailed look at how consumers are spending their money. Importantly, the panel distinguishes between spending that is done in-store, and will therefore be affected by stay-at-home orders and retail shutdown policies, and online/essential retail, which is not affected by the laws.

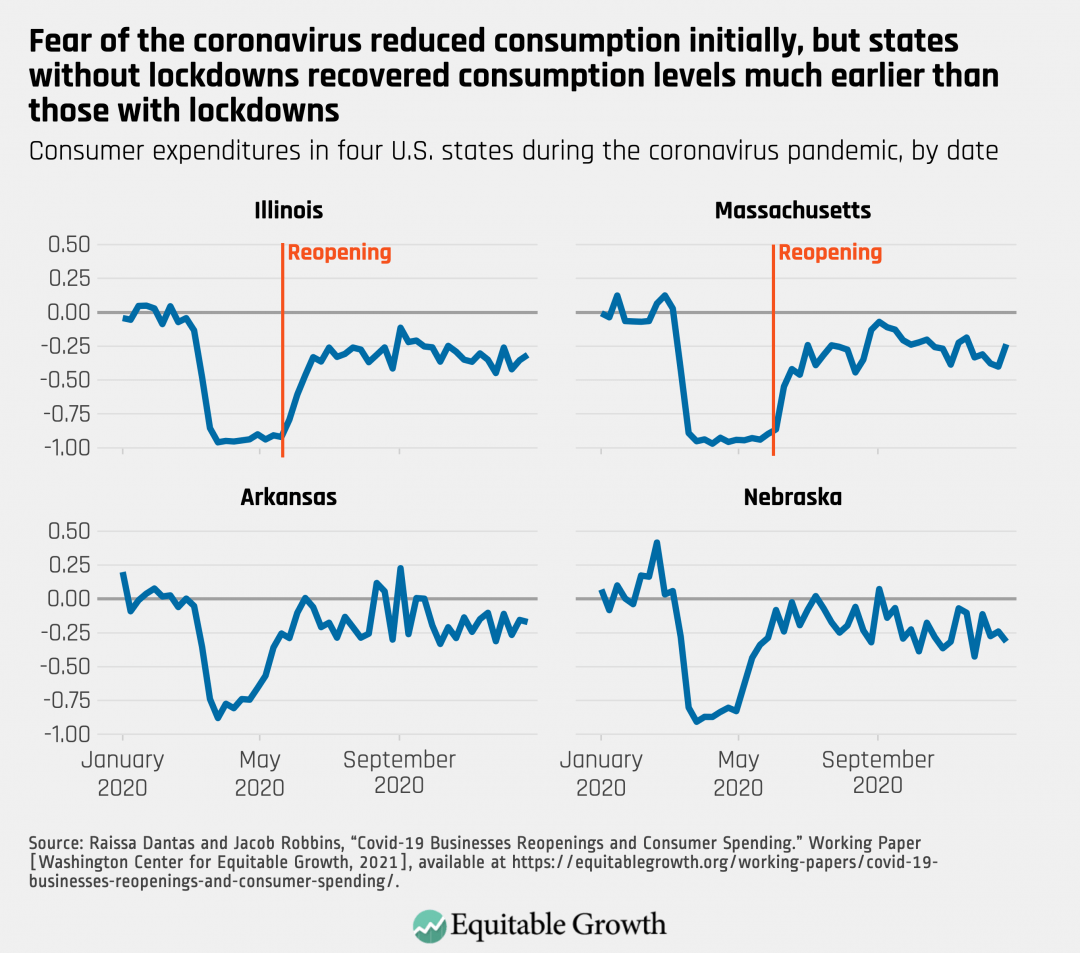

To summarize our findings, we present a case study of four states in Figure 2 below. Two of them—Illinois and Massachusetts—instituted retail shutdowns, while two others—Nebraska and Arkansas—did not. At the beginning of the lockdown, nonessential in-store spending fell close to zero in all four states, even those that did not institute shutdowns. In these early weeks, the fear of COVID-19 was the driving force behind the decline in retail spending, since spending declined by similar amounts even in states without lockdowns. After a few weeks, however, spending sharply increased in the two states without lockdowns, Nebraska and Arkansas, while spending remained near its lows in Illinois and Massachusetts, where lockdowns were still in effect. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

We find that when states reopen, the effect on consumption is immediate, with sharp and large increases in spending. The raw data thus suggest that in the early weeks of the spread of COVID-19, spending declines were mainly driven by fear of the disease, and the restrictions put in place by governments were not “binding,” meaning that even in their absence, spending would have decreased. By mid-April and May, however, the fear of COVID-19 had somewhat subsided, and the restrictions on consumer behavior were binding constraints and, when lifted, caused large increases in retail spending.

The restrictions on nonessential in-store spending did not simply shift spending into other retail categories. Retail shutdown policies are associated with a 10 percent decline in aggregate retail spending and restaurant shutdown policies with a 9 percent decline. The recovery in retail spending displayed in Figure 1 is thus partially driven by the end of the lockdowns. We estimate that 34 percent of the trough-to-peak recovery was caused by retail reopenings and 15 percent of the trough-to-peak recovery in restaurant spending was due to restaurant reopenings.

As the coronavirus vaccines continue to proliferate and consumers become comfortable dining indoors, shopping in stores, and going to movies, spending will continue to recover, and it is likely that the remaining constraints on restaurant and entertainment capacity will become binding. In making reopening decisions, then, state and local governments must not chase the false idol of aggregate GDP growth and unemployment policies that punish workers, but rather, should wisely choose public health and long-term prosperity.

The Biden administration has prioritized fighting the coronavirus pandemic and resulting recession through vaccinations and supporting those who cannot work through expanded federal unemployment benefits and economic recovery payments. This is the way forward as scientists and vaccine manufacturers continue to assess the threats to public health posed by new variants of the coronavirus. These priorities must continue.