“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other social scientists to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability.

In this installment, Equitable Growth’s Executive Director and Chief Economist Heather Boushey talks to Brad DeLong of the University of California, Berkeley and Marshall Steinbaum of the Roosevelt Institute, her fellow editors of the soon-to-be-released After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality. The three co-editors talk about the arguments in Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, what Piketty might have missed in the book, and what work the book and the new edited volume might inspire.

Heather Boushey: I am so excited that we are here finally to discuss After Piketty. Many of the people who may be reading this column may not actually have kept a copy of Piketty on their night stand and may not remember all the ins and outs, so I want to start off our conversation by asking you, first, what are the key takeaways from Piketty about the effects of inequality on our economy and our society, and second, how does the election of Donald Trump strengthen or weaken Piketty’s analytical, political, economic case?

Brad DeLong: Well, let me just deal with the second, and let me begin by saying that I think the election of Donald Trump significantly strengthens Piketty’s case. There is the view that democratic governments are kind of rational or semirational processes in which voters have preferences and those preferences are based on the assessments of issues, and that politicians who have both ideological goals but also careerist goals find themselves pushed to hug the center so that they can get re-elected so that they can do good things, and that in a democratic republic, policy evolves forward in a rational way, very much in contact with the will of the median voter.

That just doesn’t fit the election of someone like Donald Trump at all. He just does not come out of that particular view of the world. Instead, it’s much more congenial to the view underlying Piketty, which is that when the rich have an enormous amount of wealth, they are able to broadcast their point of view through society, and that the natural state of an industrial market economy with high inequality is that inequality reinforces itself.

BOUSHEY: It’s so striking how quickly it’s changed. Marshall, do you want to take a stab at these questions?

Marshall Steinbaum: I agree with Brad that certainly the idea that the political system represents a natural check on the growth of inequality has definitely been drawn into question by the election outcome, and more generally by the recent political history in the United States. I think what the election showed is you can have an economic policy consensus that yields higher and rising inequality, but doesn’t necessarily mean that you are immunized against the sort of political backlash that we experienced with the election of Donald Trump. The consensus that has governed American economic policy for decades is sort of radically overthrown by the voters when they get the chance.

So, to answer the first question, I would say that politics does not represent some sort of natural check on rising inequality. And that was certainly borne out with the election results. What Piketty might see as the natural operation of a capitalist economy yields ever-rising inequality, until some sort of external force comes to intervene and have some sort of crisis that destroys the accumulation of capital. I think that’s probably the most controversial aspect of Piketty’s argument. What is the economic force that yields ever-rising inequality through what Piketty would call the natural operation of capitalism, and then what form does the course correction take that ends up reducing inequality, and is that the sort of thing that is guaranteed to happen?

I think Piketty would say no. So, you have an economic system that has some sort of order to it, but that order is not a stable one because inequality continues to grow. And then you have the chaotic political phenomena that may or may not intervene in unpredictable ways.

DELONG: So, what’s wrong with simply “r is greater than g” as the thing that drives it? That the standard neoclassical economic response that r is greater than g doesn’t matter because people want to spend something like 3 percent of present discounted value of their wealth every year, doesn’t really apply to a plutocracy, or it’s very hard to spend that much money on yourself.

And so whether you do spend money, it’s because you have other purposes—political or transformational or one sort or another—in mind. And one of those other purposes might well be to continue the ability to transform society the way you want it over and over again. And then, as long as r is greater than g and as long as there is no strong consumption motive, that serves to push the rate of accumulation back below the average rate of profits. That’s Piketty’s argument, and why isn’t that a clearly complete explanation right then and there?

BOUSHEY: Both of you in your answers about Trump’s election seem to imply that many people who voted for Trump did so because they wanted to see a change in the way the economy works so that it actually benefits more working people.

DELONG: Well, the guy did lose by 3 million votes, to start with. So it’s not that bad. The guy did lose by 3 million votes.

BOUSHEY: Right.

STEINBAUM: I would say that this was just a rejection of the status quo and the establishment, and when that happens from the right, it takes the form of a racist demagogue. Trump is a new phenomenon in the United States, but it is not a new phenomenon in world history, whereby essentially a radical challenge to the political establishment rises up. And when those challenges are successful, it’s because some element of the mainstream tries to co-opt them and ally themselves in order to gain leverage in the political game that that mainstream faction has been playing.

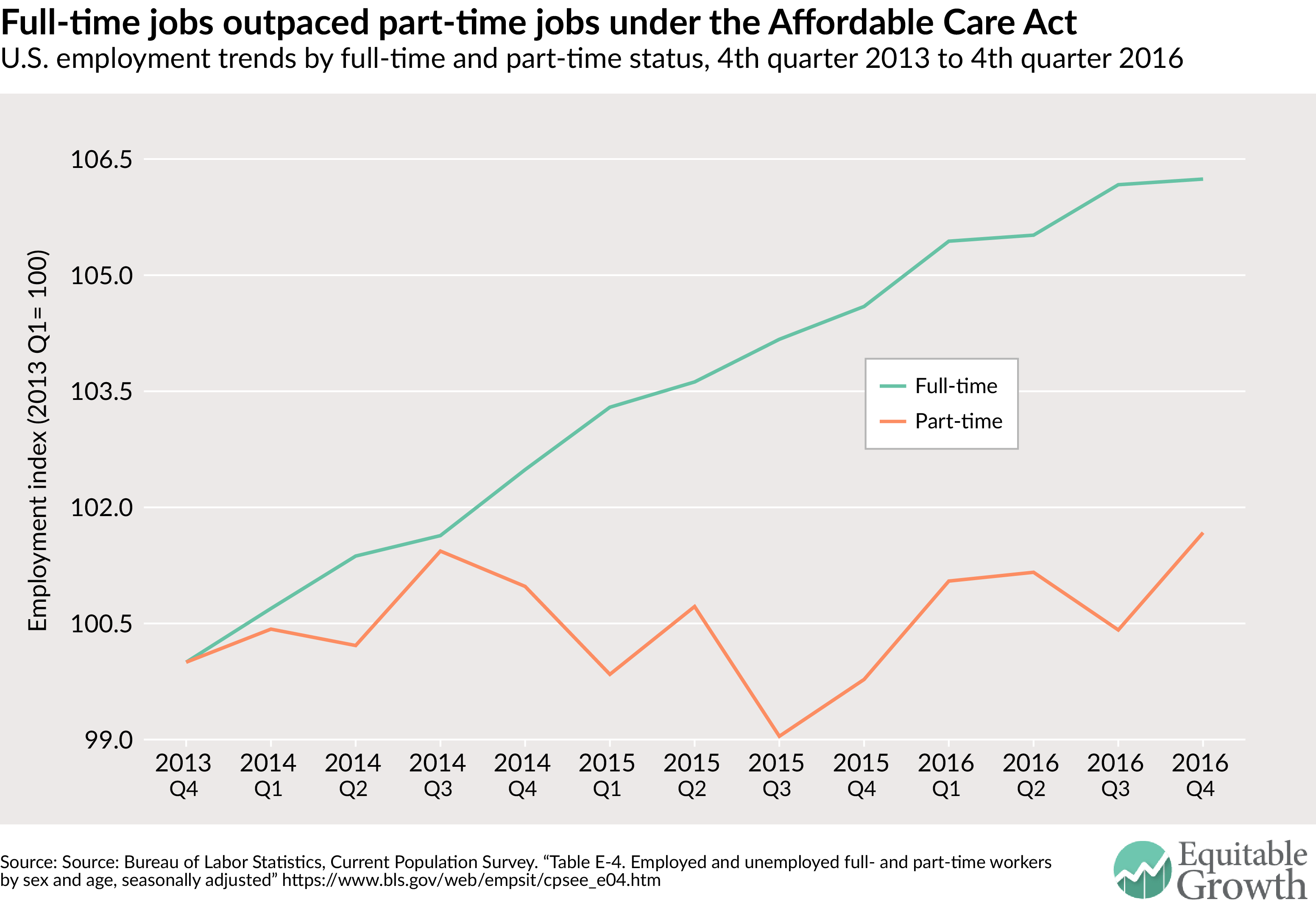

DELONG: If you take the canonical unusual Trump voter, he’s supposed to be some kind of working-class guy in semirural Pennsylvania whose life really hadn’t turned out the way he thought it would because the unionized jobs that he thought were inevitable in the prosperous community he thought he was going to be living in kind of vanished underneath his feet. We can argue back and forth over whether that’s actually what is going on or whether that’s simply journalists grabbing for a story that sounds good, no matter how much or little empirical support it has. But for that guy, the thing that changes his life chances the most is the Affordable Care Act—something that gives someone who doesn’t have stable employment in a relatively high-wage job the access to the healthcare system that adverse selection has been blocking him out of, just at the time when he’s too young for Medicare and yet too old to be able to plausibly afford any private insurance off of his own dime.

That’s a huge distributional move. So, to the extent that you are actually changing people’s lives, the Affordable Care Act did it. And as we’ve seen over the past three weeks, when all of a sudden what [Speaker of the House] Paul Ryan thought initially was a slam-dunk—repeal of large parts of the Affordable Care Act—turned to run into a huge buzz-saw, as the exchanges had Republican constituencies. Similarly, the Medicaid expansion had beneficiaries who called Republican office holders. And Republican state governors such as John Kasich of Ohio made it clear that they valued the Affordable Care Act’s freedom to extend Medicaid to a truly remarkable degree.

So, Obama did it. Obama did it big time. And yet it did not trickle down into the gestalt of the election, or indeed, is not reflected in what people thought they were voting for.

BOUSHEY: Well, there are benefits and there are jobs. I think that the counterpoint to your argument is the way people felt about trade and manufacturing, where it still is not clear to me that they are going to get what they want, but at least they’ve gotten the president who’s gotten up many days and said that he’s created real manufacturing jobs in those communities and is elevating that. And I think that that’s an interesting distinction as well, that healthcare is a benefit versus a lot of these Trump voters also really can be focused on the job component of their standard of living.

DELONG: Ronald Reagan was absolutely awful for the manufacturing jobs of the Michigan Reagan Democrats. He pushed the dollar up by 50 percent. And lo and behold, that just sent Midwestern manufacturing a signal that it should shut down. Today, the dollar is up by 10 percent since Trump’s election, and whatever legislation rolls through Congress is likely to involve a large tax decrease for the rich, in which case we will see another bigger dollar cycle than we have now. Let the dollar go up by another 10 percent, and that’s a hit to the manufacturing employment that is much, much larger than China’s entry into the World Trade Organization or any plausible effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

BOUSHEY: Do we think that we know yet whether Piketty’s core argument is correct? What tweaks to Piketty’s argument need to be addressed more thoroughly, moving more thoughtfully and thoroughly moving forward?

STEINBAUM: I think the key question is basically, in Piketty terms, why does r not fall as capital is accumulated as a neoclassical model of the macroeconomy would predict? This is a very clear finding in the aggregate data that Piketty presents over this long time horizon—that the return to capital is more or less constant even as the amount of capital in the economy is not constant at all. And that’s a huge challenge to a Ricardian classical or neoclassical theories that come from it.

I don’t think that we have the definitive answer to that. I think where the research has gone, concurrently with the publication of this book and then subsequently, is essentially, why is the capital share or the profit share in the economy so high, and what are the strategies by which owners of capital have redirected the flow of rents to themselves, when supposedly competitive pressures would have been pushing down the return to capital.

I think that there’s a lot of different dimensions on which that has transpired, but the one that I think is kind of the overarching theme in what could possibly explain that phenomenon is the unification of the ownership of capital and the management of firms into one interest through various corporate structures that facilitate the increased ability of that unified ownership-management alliance to essentially operate the economy to its own benefit and to the detriment of every other stakeholder.

DELONG: Am I the only person who thinks the answer to this is pretty obvious—that Piketty made a mistake in calling the book Capital in the Twenty-First Century rather than Wealth in the Twenty-First Century? Because you may well believe—and in fact I firmly do believe—that the rate of return on actual useful machines and buildings declines as the proper physical capital-to-labor ratio increases.

The problem is that these marginal products of real physical capital, machines, and buildings is only a small part of the returns flowing to wealth, which are composed of monopoly rents of one sort or another, either acquired by antitrust forbearance on the one hand or by government license on the other, plus a whole bunch of other things, all the way down to the middle class and rich of the previous generation who don’t really understand that their investment advisors do not act as though they have a fiduciary duty toward them. Wealth deployed in order to maintain its own rate of return is a much easier thing to understand than how is it that if there are four machines competing for each worker, then workers are unable to drive down the price of renting any one of them.

BOUSHEY: That’s a very good point, Brad, and one of the things that I know Marshall has written about recently—the market concentration at the top of the income spectrum is a part of what that wealth is. Marshall, you’ve thought about that issue a lot recently and you’ve written on it. Do you want to speak to that?

STEINBAUM: Sure. I think that a lot of the anticompetitive behavior that we observe in the economy operates through some version of the unification of ownership and management, such that firms are increasingly run to the benefit of their shareholders/managers since they are the same, and at the expense of all the other stakeholders. So, that takes the form of classic anticompetitive behavior, higher prices than the market would otherwise bear if it were fully competitive—say because of common ownership at the shareholder level—across all the firms in an industry, giving rise to an incentive on the part of the managers of those firms not to compete very hard on price.

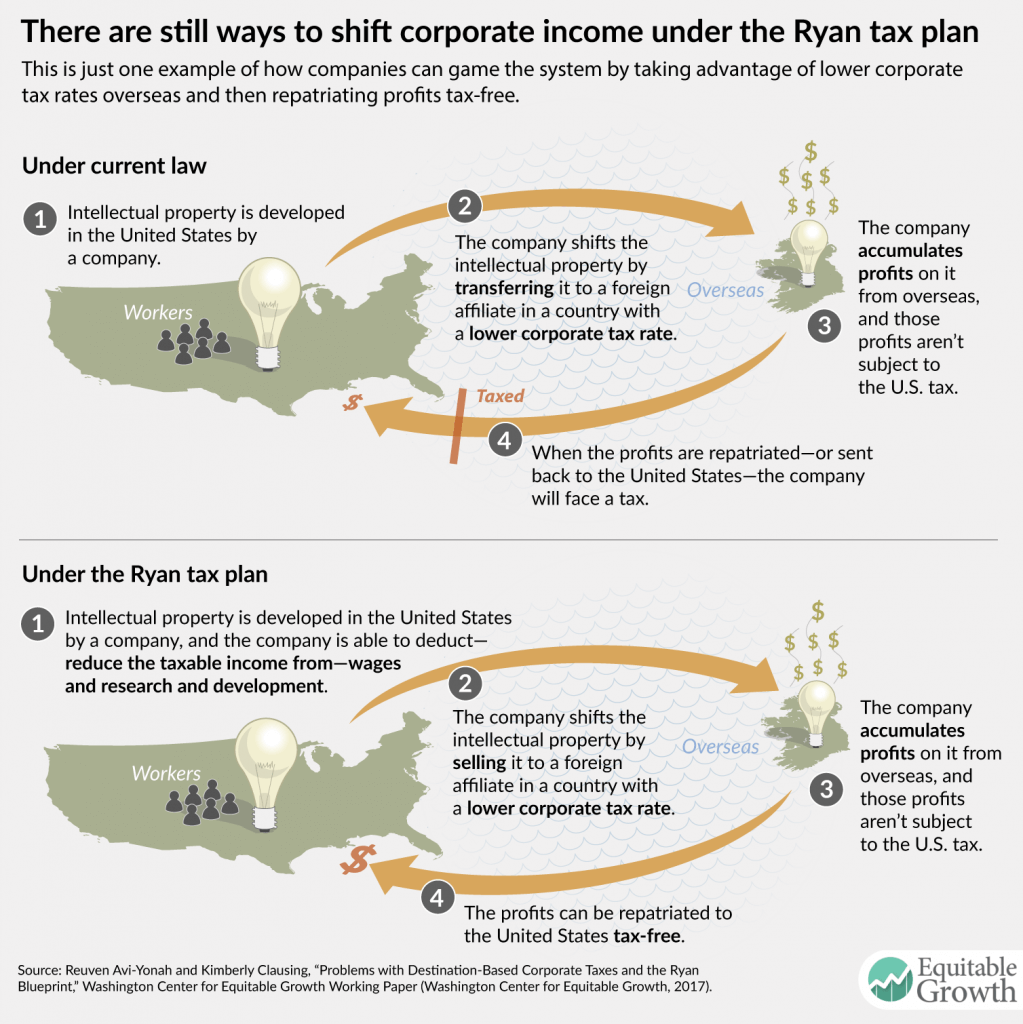

I think the interesting phenomenon here in the context of the corporate tax debates is why aren’t firms investing and what’s going on with these huge piles of retained earnings and profits that are not being plowed back into the firm to expand operations or engage in research and development. There’s a very interesting literature that’s growing up about essentially the rise in corporate net savings worldwide, but especially in the United States. This has a lot to do with [University of California, Berkeley economist] Gabriel Zucmans’s excellent research on tax havens, and in general the incentive to accumulate capital on the balance sheets of large incumbent corporations and/or pay it out to shareholders in the form of buybacks and dividends.

There’s an excellent new paper by German Gutierrez and Thomas Philippon [at New York University’s Stern School of Business] about trying to explain the rise of corporate net savings, and specifically the fact that corporate investment is well below what a Tobin’s q-type theory would predict. That means you’re going to need some sort of version of changing corporate governance that is going to say, well, if you want to engage in this new project, you’ll have to pass a higher bar in terms of the return on that project versus the much more present and powerful claim that the shareholders have to those earnings that you’ve gotten from past activities—and that, in many contexts, you don’t want to actually pay it out because thanks to tax havens, the corporation becomes the most effective tax shelter. So better to just earn it and keep it in an overseas subsidiary.

There’s another paper by Steven Kamin and Joseph Gruber at the Fed that more or less looks at the same phenomenon but across countries. There’s a paper by Loukas Karabarbounis [at the University of Minnesota] and Brent Neiman, and Peter Chen [at the University of Chicago] that also talks about the rise of corporate net savings. I think this is an as-yet unexplained phenomenon but definitely it has a lot to do with this unification of shareholder and management control. So, that is a totally distinct story about how you might keep r high even as capital is accumulated than the technological substitution story that Piketty tells.

BOUSHEY: How do you hope to reignite the debate with After Piketty? Brad, let’s go to you first. What do you want to accomplish with our book?

DELONG: Simply keep plugging away. All one has to do is argue a little more coherently and get a slightly better megaphone, and we can change people’s minds and actually have a huge effect on the political economy of the 21st century.

STEINBAUM: Yes, I thought that what Brad just said was interesting because he more or less didn’t talk about what I would call the mainstream frontier of the academic economics research agenda. I think Capital in the Twenty-First Century is very much intended as an economics book, and its ambivalent reception among academic economists tells you a lot about a lot of things. And one of them is that it’s doubtful that the grand solutions to our problems—if you can characterize them that way—are not going to be found in that intellectual milieu. So, I think that if you ask the average academic economists, say of my generation of people who are getting started and trying to get tenure in departments, they would tell you that Piketty has had no effect, that we are all just continuing to do what we were doing before, and essentially that’s going to be it from now on.

Whereas, I think where we started this conversation talking about high electoral politics and then the federal election of 2016, and from there down to public debate at every level in the United States, Piketty had a tremendous effect. He had a huge influence on public debate about economics and the issues before us. And that disconnect between the heights of the academic economics profession and the life that all of the people in the rest of the economy live, and certainly in the conversations about the economy that they talk about, does not bode well for the economists. I think essentially they are used to having influence that derives from a position of prestige and public trust that does not survive in the Trumpian era, or you can say survive in the Pikettian era. And so I think that’s kind of the situation where we are now.

I feel like we are shaking our book and shaking Piketty’s book in the faces of academic economists and saying, you know, pay attention. And if you weren’t paying attention before, you should be paying attention now, after Trump. Plenty of scholars that have done original work in that area have, at least on their face, pitched their work as being in opposition to Piketty’s theory of rising inequality, though whether it is in fact in opposition to it I think is much less clear. So, there is definitely new empirical research that has gotten a lot of attention, has gotten a lot of young graduate students their first job, that you could tie to Piketty’s own agenda, if not directly to Capital in the Twenty-First Century itself.

But I do think that it will be interesting to see if what might be considered the most publicly influential and ground breaking work in economics in the next 10 years emerges possibly not from academic departments.

DELONG: Well, I think it has had one important impact on mainstream economics in that mainstream economics always tends to head for aggregates of wealth and say that distribution is an interesting question and we should research it. But it’s overwhelmingly a political question, and so except for us economists reporting elasticities and offsets, we should leave it to the political scientists. And Piketty pushes us back toward a more utilitarian view, that economics is not about piling up wealth but piling up utilities, and in any world in which there is decreasing marginal utility to wealth, which economists certainly believe there is, then inequality matters a great, great deal.

STEINBAUM: Yes. I mean, I would put it less theoretically than that. I think that, you know, the best new research in economics is being done with large data sets in which inequality is just an obvious fact. And that is the main phenomenon to be explained. And so we will have lots of arguments about whether Piketty’s theory of inequality is right.

I mean, in fact you could say that the book is not really about a theory of why some people are rich and other people are poor, but by presenting the inequality statistics that he has spent his life putting together, he made that question and the fact that economics does not have a very convincing answer to that question front and center.

And so anybody who writes a paper about this or articulates a theory about why some people are rich and other people are poor owe something to Piketty, whether or not they want to admit that.

BOUSHEY: I’m going to stop us right there because that was a great sentence to end on. It has been a real pleasure to work on this with the two of you. Thank you both.

DELONG: Thank you very much.

STEINBAUM: Thanks.