Must-See: (November 18, 2015): Do Millennials Stand a Chance? Giving the Next Generation a Fair Shot at a Prosperous Future:

Wednesday, November 18, 2015 from 8:00 AM to 11:00 AM (PST) :: California Memorial Stadium :: 210 Stadium Rim Way

Must-See: (November 18, 2015): Do Millennials Stand a Chance? Giving the Next Generation a Fair Shot at a Prosperous Future:

Wednesday, November 18, 2015 from 8:00 AM to 11:00 AM (PST) :: California Memorial Stadium :: 210 Stadium Rim Way

Must-Read: I’m with Larry Mishel here: Why do people think Uber-type companies are an important deal, again? Uber, Airbnb, Craigslist… and what else?

: Uber Is Not the Future of Work: “The rise of Uber has convinced many… that freelancing via digital platforms is becoming increasingly important…

…[But] a look at Uber’s own data about its drivers’ schedules and pay reveals them to be much less consequential than most people assume… distracts from the central features… that should be prominent in the public discussion: a disappointingly low minimum wage, lax overtime rules, weak collective-bargaining rights, and excessive unemployment, to name a few…. Curiously, the best evidence of Uber’s relatively small impact on the American labor market comes from data released and publicized by the company itself. David Plouffe, an Uber strategist… ‘Here in the U.S., there are more than 400,000 active drivers… half the drivers work less than 10 hours per week… a third of drivers said they used Uber to earn money while looking for a job.’… Driving mostly for supplementary income on a transitory basis conflicts with the notion, promoted by the company, that Uber, and gig work more generally, are a major feature of how people will earn a living in the future…

Must-Read: Something very, very peculiar is going on with middle-aged American whites in the Bush 43 and Obama years–much more so for women–and it is distinctly odd:

Andrew Gelman: : Asking the Question Is the Most Important Step: “I worked super-hard to make the graph… that helped me understand what was going on…

…But, from the social science perspective, what’s far more important is asking the question in the first place, which is what Case and Deaton…. That’s what got the ball rolling. (And, to be fair, they also rolled the ball most of the way.) I’m happy to have refined their analyses and, as noted yesterday, I wasn’t so thrilled by one of Case’s offhand remarks, but let me emphasize that all this discussion is predicated on their effort, on their knowing what to look at, which in turn derives from their justly well-respected research on public health and economic development. That’s the big picture….

Statisticians such as myself have our place in the research ecosystem, but all the bias correction and modeling and clever graphics in the world won’t help you if you don’t know what to look at. And in this particular example, I had no idea of looking at any of this until I was pointed to Case and Deaton’s work…. None of our contributions could’ve happened without the work by the original authors. It’s not Us vs. Them. It’s never Us vs. Them. It’s Us and Them. Or, perhaps more accurately, THEM followed by a little bit of us. And that’s one reason I want them to respect and understand us, not to fear us and be defensive”

Must-Read: The question I always find myself going back and forward on is this: Do strong unions primarily reflect or primarily cause a high labor share of income? And I find my views on this question both disturbingly ungrounded in evidence and disturbingly volatile…

: The Decline of Labor; The Increase in Inequality: “Between the end of the Second World War and the early 1970s, the American labor movement was one of the reliable signposts…

…that defined the parameters of American life. But if history has taught us anything, it’s that the signposts of our culture, economics, and politics are continually evolving, even as we believe they will be perennially rooted…. No less a figure than Dwight Eisenhower assumed an America that would always have strong unions…. Timothy Noah, relying on the work of economists Claudia Goldin and Robert Margo, describes this period in his book about American inequality, The Great Divergence (2012), as one in which “incomes became more equal and stayed that way.” Union density peaked at about 1/3rd of the non-farm workforce in the decade following the second world war…. States like Alabama and Tennessee had “low” union density rates in the high teens that were equal to the “high” density rates of “union states” like Michigan today….

During the 1972 election, Meany’s AFL-CIO, enraged by George McGovern’s opposition to the Vietnam War and the influence of the New Left and the counter-culture that permeated his campaign, remained neutral rather than endorse the Democratic candidate. Organized labor was so important to the Democrats that the wily Republican president, Richard Nixon, had courted Meany over several rounds of golf and sought to identify the administration with what Nixon and his top aides took to be the cultural symbols of blue collar, white manhood. The Federation’s neutrality was his reward…. By the middle of the 1980s, history had fooled the present again: the “secure place” of American labor which Ike had spoken of so confidently in 1952, turned out to be, in fact, evanescent. By 1991, union density had declined to just 16%. (It is now about 11%.)… In 1978, despite the most massive lobbying drive in union history, Carter placidly watched a modest labor reform bill be filibustered to death by Republicans and Southern Democrats in an overwhelmingly Democratic Congress….

Why did this happen?… For some of the same structural, macro-economic reasons it has declined in almost every advanced country… but… also occurred for reasons intrinsic to the American political economy…. Just as labor and the economic base of much of its membership lost altitude, unions faced the egalitarian necessity to modernize themselves. This was not without complications. Title VII of the1964 the Civil Rights Act accelerated a much longer struggle by black workers to have full and equal representation within unions. Arguments against racial (and gender) discrimination, especially in building trades and manufacturing unions, that had mostly been ignored by the NLRB, gained salience before the new Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)….

Labor… today… remains the most effective institutional bulwark against income inequality. Within its blue state zones of urban power, labor has, effectively, fought inequality via the “fight for 15” led by the still formidable SEIU, and promoted the passage of minimum wage laws in states and cities around the country. Unions, despite their inability to win legislation of direct benefit to themselves, still lead efforts to augment social insurance and regulate companies and banks…. Advancing beyond their previous racism and sexism, unions are, in significant ways, better advocates for such concern today than they were when George Meany was refusing to endorse the March on Washington and, then during the McGovern campaign, railing about the Democratic party being seized by “people named Jack who look like Jill and smell like johns.”…

The numbers of union members and the dollars in the stagnant paychecks of millions of American workers tell an unhappily congruent story. If, in subsequent years, union membership numbers don’t increase dramatically, workers’ paychecks aren’t likely to increase very much either.

Must-Watch: (November 18, 2015): Do Millennials Stand a Chance? Giving the Next Generation a Fair Shot at a Prosperous Future:

Wednesday, November 18, 2015 from 8:00 AM to 11:00 AM (PST) :: California Memorial Stadium :: 210 Stadium Rim Way

Must-Read: : America’s Labour Market Is Not Working: “In 2014… close to one in eight…

…of US men between the ages of 25 and 54 were neither in work nor looking for it… far higher than in other members of the group of seven leading high-income countries: in the UK, it was 8 per cent; in Germany and France 7 per cent; and in Japan a mere 4 per cent…. The proportion of US prime-age women neither in work nor looking for it was 26 per cent, much the same as in Japan and less only than Italy’s…. Participation rates for those over 16. These fell from 65.7% at the start of 2009 to 62.8% in July 2015… 1.6 percentage points of this decline was due to ageing and 0.3 percentage points due to (diminishing) cyclical effects…. Yet… the UK experienced no decline in labour-force participation after the Great Recession, despite similar ageing trends…. Back in 1991, the proportion of US prime-age men who were neither in work nor looking for it was just 7 per cent. Thus the proportion of vanished would-be workers has risen by 5 percentage points since then…. What has been happening to participation of prime-aged women is no less striking….

The comforts of idleness cannot be a plausible explanation since the US has the least generous welfare state among high-income countries. High minimum wages cannot be blocking job creation…. In the case of prime-aged women, the absence of affordable childcare would seem a plausible explanation…. The numbers with criminal records created by mass incarceration might also help explain the difficulty in finding jobs…. The relentless decline in the proportion of prime-aged US adults in the labour market indicates a significant dysfunction. It deserves attention and analysis. But it also merits action.

Must-Read: : Quality Early Childhood Education: Enduring Benefits: “The recent debate around the new Vanderbilt study…

…Opponents and proponents of early childhood education alike are quickly turning third-grade assessments into a lopsided and deterministic milestone instead of an appropriate developmental evaluation in the lifecycle of skills formation. There is a reoccurring trend in some early childhood education studies: disadvantaged children who attend preschool arrive at kindergarten more intellectually and emotionally prepared than peers who have had no preschool. Yet by third grade, their math and literacy scores generally pull into parity. Many critics call this “fadeout” and claim that quality early childhood education has no lasting effect. Not so…. Too often program evaluations are based on standardized achievement tests and IQ measures that do not tell the whole story and poorly predict life outcomes.

The Perry Preschool program did not show any positive IQ effects just a few years following the program. Upon decades of follow-ups, however, we continue to see extremely encouraging results along dimensions such as schooling, earnings, reduced involvement in crime and better health. The truly remarkable impacts of Perry were not seen until much later in the lives of participants. Similarly, the most recent Head Start Impact Study (HSIS)…. The decision to judge programs based on third grade test scores dismisses the full range of skills and capacities developed through early childhood education that strongly contribute to future achievement and life outcomes…. Research clearly shows that we must invest dollars not dimes, implement high quality programs, develop the whole child and nurture the initial investment in early learning with more K-12 education that develops cognition and character. When we do, we get significant returns…. Yes, quality early childhood education is expensive, but we pay a far higher cost in ignoring its value or betting on the cheap.

Nick Bunker says:

: A Kink in the Phillips Curve: “Look at the relationship between wage growth and another measure of labor market slack, however, [and] the [Phillips-Curve] relationship might hold up. Take a look at Figure 1:

This is entirely consistent with inflation-expectations anchored near 2%/year–or inflation so low that shifts in inflation expectations are not a thing–and a Phillips Curve that gradually loses its slope as wage growth approaches the zero-change sticky point:

This is entirely consistent with inflation-expectations anchored near 2%/year–or inflation so low that shifts in inflation expectations are not a thing–and a Phillips Curve in which the right labor slack variable is some average of prime-age employment-to-population and the (now normalized) unemployment rate:

It is really not consistent with any naive view that holds that the Phillips Curve has the unemployment rate and the unemployment rate alone on its right-hand side, and that inflation is about to pick up substantially with little increase in the employment-to-population ratio.

Thus not only does the right wing of the Federal Reserve expecting an imminent upswing of inflation because of MONEY PRINTING! have it wrong, it strongly looks as though the center of the Federal Reserve has it wrong too…

Must-Read: It seems to me that there are two questions: 1. Should the the aggregate of the minimum wage and the earned income tax credit add up to a living wage? Answer: yes. 2. what is the right mix and balance between raising the minimum wage (which will, if it is raised high enough, diminish the total number of jobs) and increasing the earned income tax credit (which will, once we are away from the zero lower bound in interest rates, require raising taxes somewhere in the system)? The minimum wage should not be considered in isolation.

Of course, minimum-wage advocates are fearful of the following: We say raise the minimum wage, they say increase the earned income tax credit instead. We say increase the earned income tax credit, they say it is more important to reduce the deficit. We say fund the earned income tax credit by raising taxes, they say lower taxes promote entrepreneurship. we say cut defense spending, they say ISIS and Iran. The shift of attention to the earned income tax credit is then seen as–which it often is–part of the game of political Three Card Monte to avoid doing anything while not admitting you are opposed to doing anything.

That is all very true.

So raise the minimum wage, and then bargain back to a lower minimum wage and a higher income tax credit if it turns out that there are significant disemployment affects.

: The Fight for 15: “Whenever I hear an argument about the possibility of raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour…

…it sounds like this. Person A, who is for it, makes the case that it’s too difficult to live on minimum wage earnings, and it doesn’t make sense for someone working full time to struggle so much to feed their kids. Person B, who’s against it, says that 15 is too high, that too many employers will be unwilling to pay for unskilled workers at that rate, and they will replace such people with machines instead of doing so. Essentially, they argue the bad will outweigh the good…. I am often Person A…. I think about what I could theoretically live on, if I had a minimum wage job, and I have extreme sympathy for people who try to.

Let’s get back to Person B’s argument. It’s weird because it sounds like Person B is arguing for the sake of the poor, but they’re ignoring the vital question of what is a living wage…. For the sake of holding on to crappy jobs that pay below living wages, and where the employees need food stamps to survive, we don’t raise the bar so they can actually sustain someone in a basic way…. As long as we live in a country where the model is that a job is supposed to support you, we should make sure it actually does.

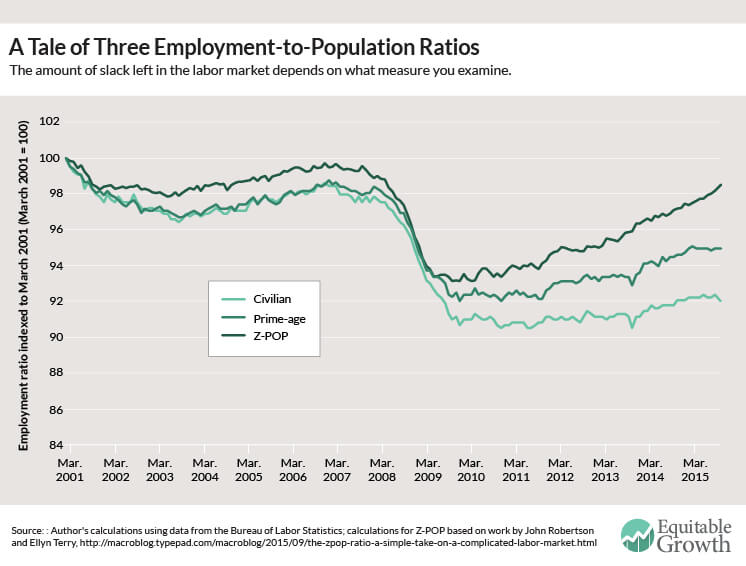

The press received the most recent labor market data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics late last week as unexpected bad news because employment growth slowed and wage growth continued to be weak. Yet the U.S. unemployment rate sits at 5.1 percent, around its range before the Great Recession. Given the lack of wage growth in the economy, it’s become quite obvious that the current unemployment rate is overstating the health of the U.S. labor market.

But exactly how much further do we have to go? A look at a few different metrics, specifically employment-to-population ratios, might shed some light on the answer.

Perhaps the surest way to know the labor market is approaching full employment is to look at wage growth. Full employment really can’t be pinned down to one specific number, but one would expect to see strong nominal wage growth (before accounting for inflation) consistent with long-run productivity growth. Given that labor productivity growth in the long run is about 1.5 percent, and the inflation rate per the Federal Reserve’s target should be 2 percent over the long term, nominal wage growth should be 3.5 percent at the very least in a healthy labor market. Current wage growth isn’t even close to that threshold yet.

But the problem in waiting for wage growth is that you really don’t know until you get there. As University of Michigan economist Justin Wolfers points out, monetary policy acts on a lag and therefore it shouldn’t ease too much for too long given the potential for inflation to pick up. Now, that might not be so terrible given central banks’ tendencies to take away the punch bowl too early in recent years. But it’d still be nice to have an idea of how much further the labor market has to go.

Enter a new statistic from researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta: the Z-POP. The statistic, formally known as the utilization-to-population ratio, is an attempt by senior policy adviser John Robertson and economic policy analysis specialist Ellyn Terry to build a more accurate representation of how well labor is being used.

The ratio counts a member of the population fully utilized unless they are officially unemployed, working part-time but wanting full-time work, or out of the labor force but wanting a job. So workers who don’t want a job—say, because they’re in school or retired—are counted as fully utilized. As Josh Zumbrun of The Wall Street Journal said on Twitter, it’s like somewhere between the U-6 unemployment rate and the employment-to-population ratio. The Z-POP in September 2015 was 92.1 percent, still below its pre-Great Recession level of 92.7 percent in December 2007.

What does this new statistic tell us about the labor market compared to more traditional measures? Take a look at Figure 1, which looks at the relative changes in the Z-POP, the civilian employment-to-population ratio, and the prime-age (25-to-54 year old) employment-to-population ratio since March 2001, the peak before the dotcom-bust recession.

Figure 1

The three measures tell different stories about the pace of the current labor market recovery. The civilian ratio, which looks at the entire working-age population, shows almost no recovery. The obvious problem with this measure is that the population has undergone a demographic transformation as the Baby Boomers have started to retire, pushing down the share of the population with a job. To adjust for this demographic change, we can look at the employment-to-population ratio for workers in their prime working years. That metric shows a more significant recovery, but it has stalled out over the course of 2015. While the Z-POP is also below its pre-recession peak, it’s much closer to that March 2001 level.

So should we believe the Z-POP or the prime-age EPOP? At this point, frankly, it’s hard to tell. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio has a history of predicting wage growth well, but it doesn’t distinguish between workers out of the labor force who want to stay there and those who’d like to jump back in. Either way, both measures indicate that we have a ways to go before seeing a truly healed labor market.