Overview

Is the U.S. unemployment rate as low as it can go? After years of a very weak labor market, during which many jobless workers gave up trying to find employment due to the lack of employer demand, many economists and analysts now believe the labor market is now as tight as it can sustainably be. The unemployment rate is close to 4 percent, and most of the participants of the policy committee of the Federal Reserve believe the unemployment rate is at or below its long-term rate.

Download File

Just how tight is the U.S. labor market?

Read the full PDF in your browser

What’s more, recent research by economist Alan Krueger of Princeton University argues that fewer workers will actively search for jobs these days due in part to opioid addiction. This kind of view, also articulated by New York Times columnist Eduardo Porter, holds that the problem in the labor market now is one of supply—a lack of available workers eager to work—rather than demand for labor among employers.

But if the current unemployment rate is indicative of a very tight labor market, then why does wage growth continue to be so tepid? If the supply of potentially employable workers is tapped out, then the price of labor—wages—should grow at an increasingly faster pace. Yet as the unemployment rate has declined and hit levels many associate with “full employment,” wage growth has yet to break out of the range of 2 percent to 2.5 percent per year. One simple explanation of this anomaly of a tight labor market with weak wage growth is that the labor market is not actually that tight.

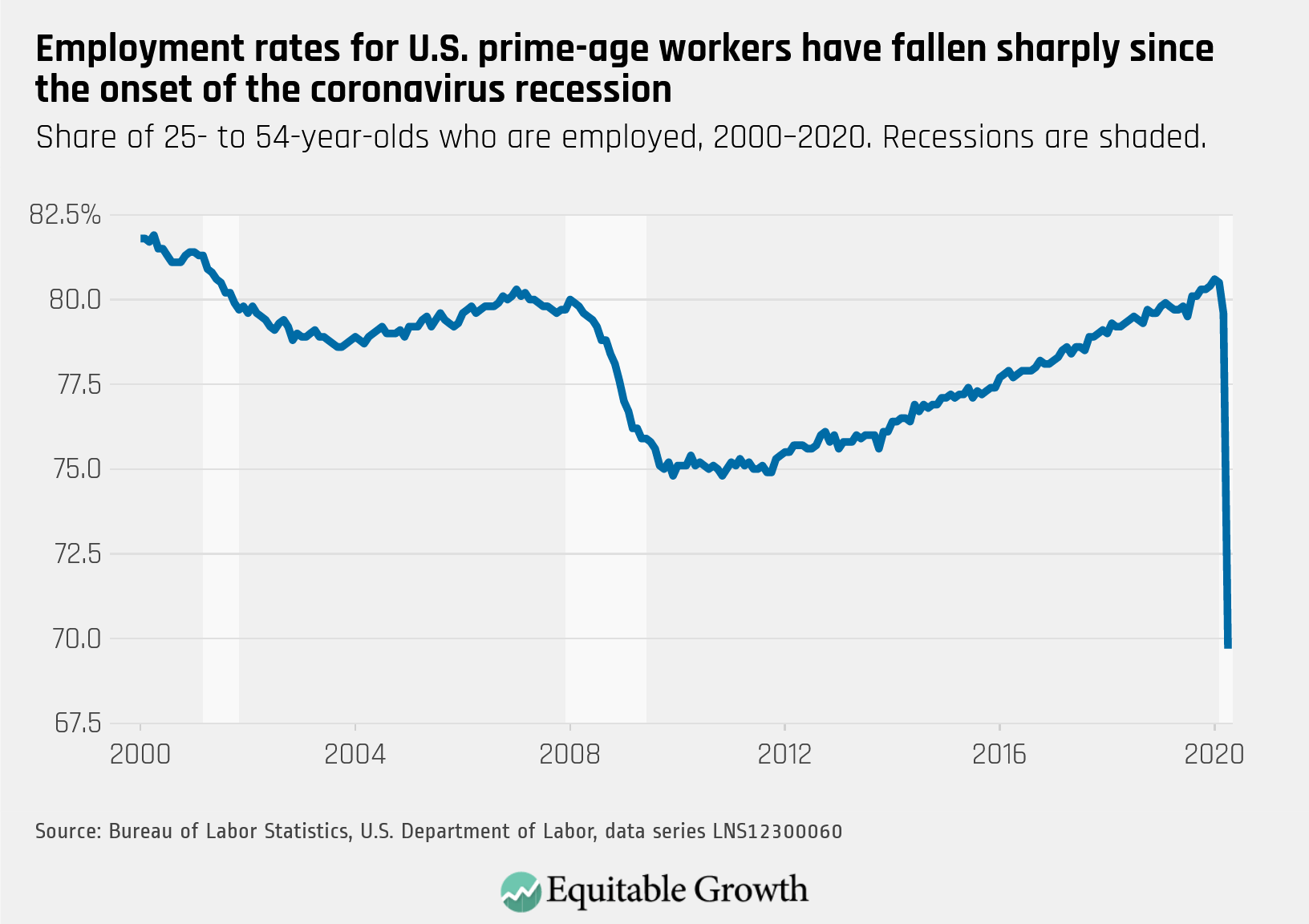

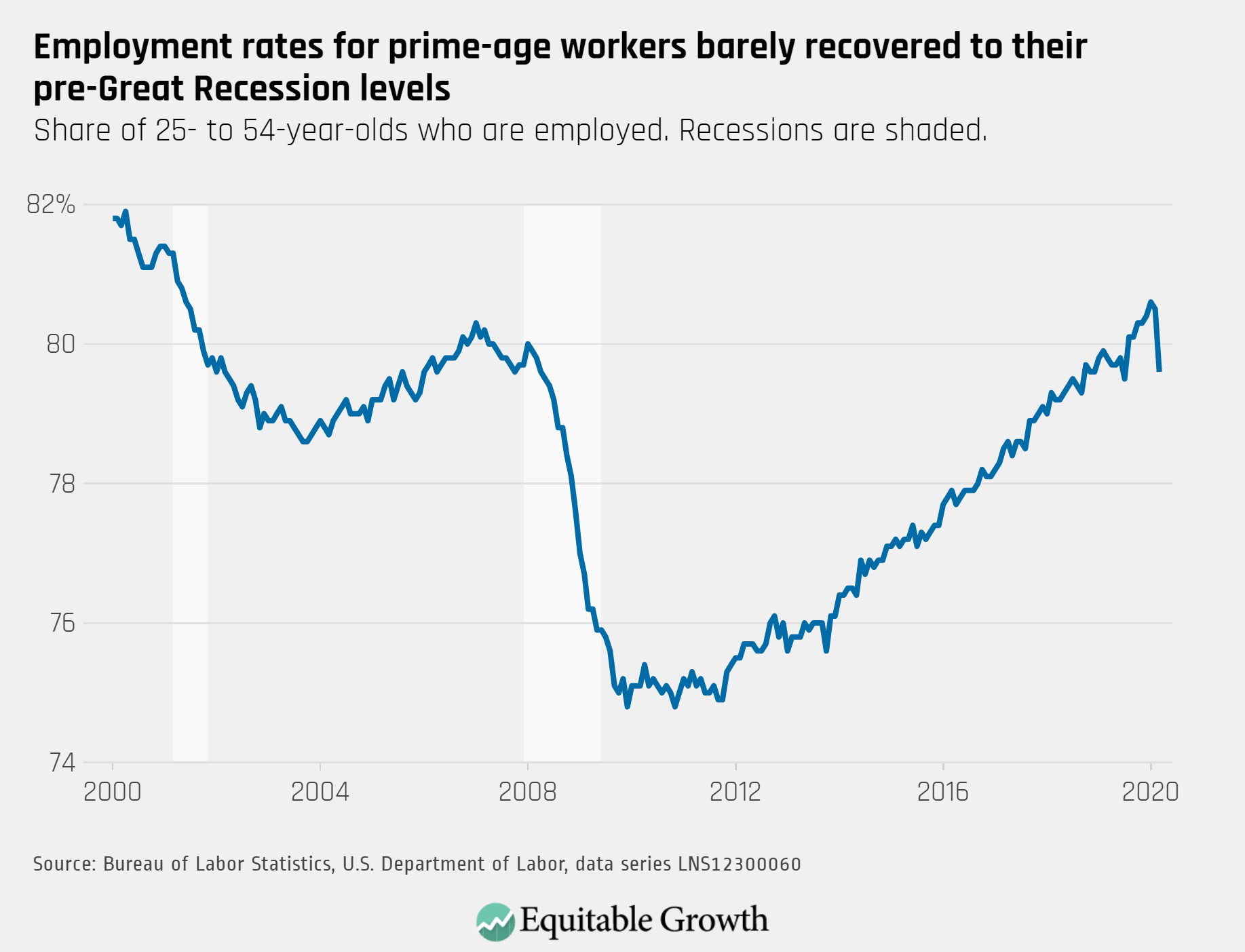

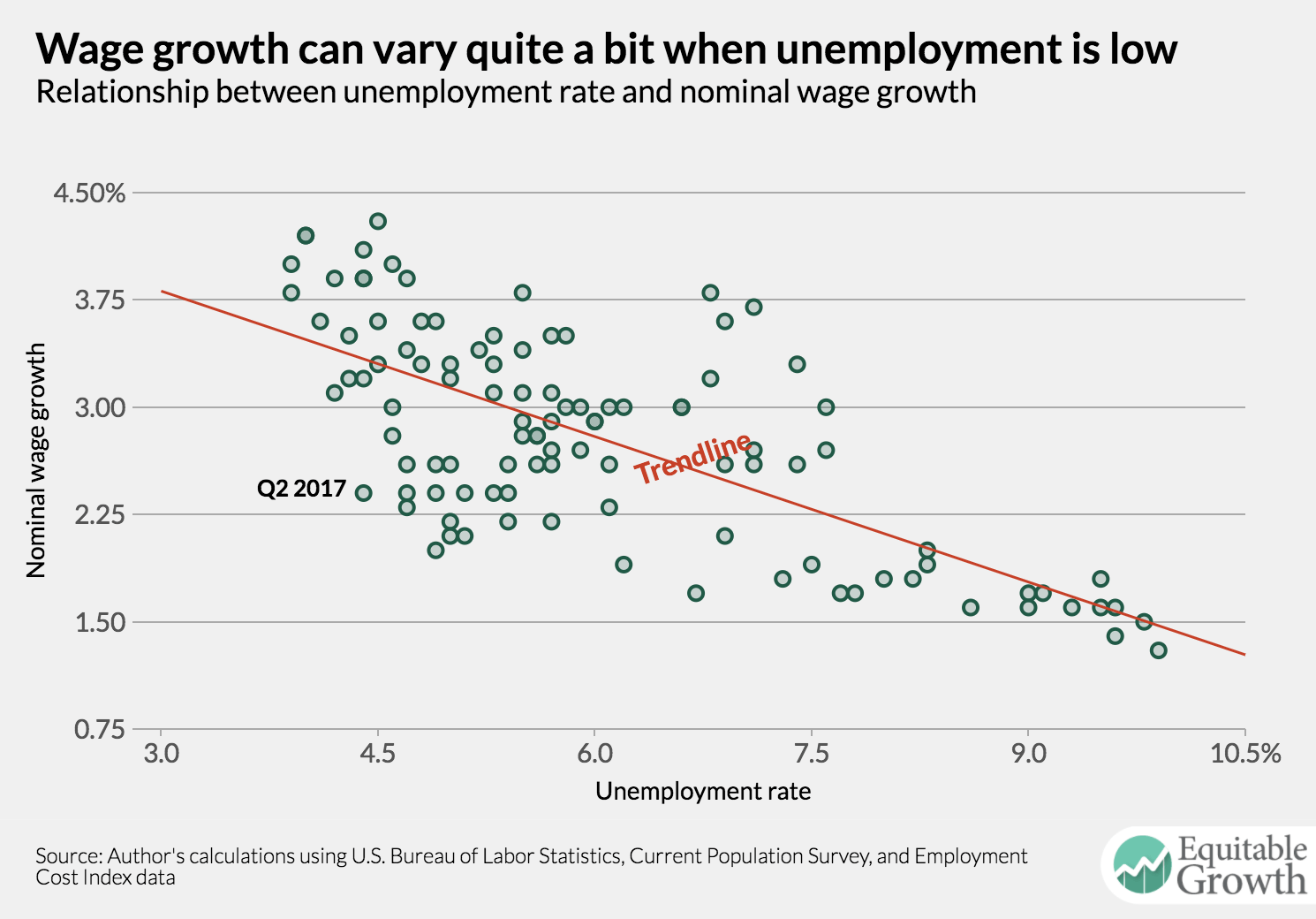

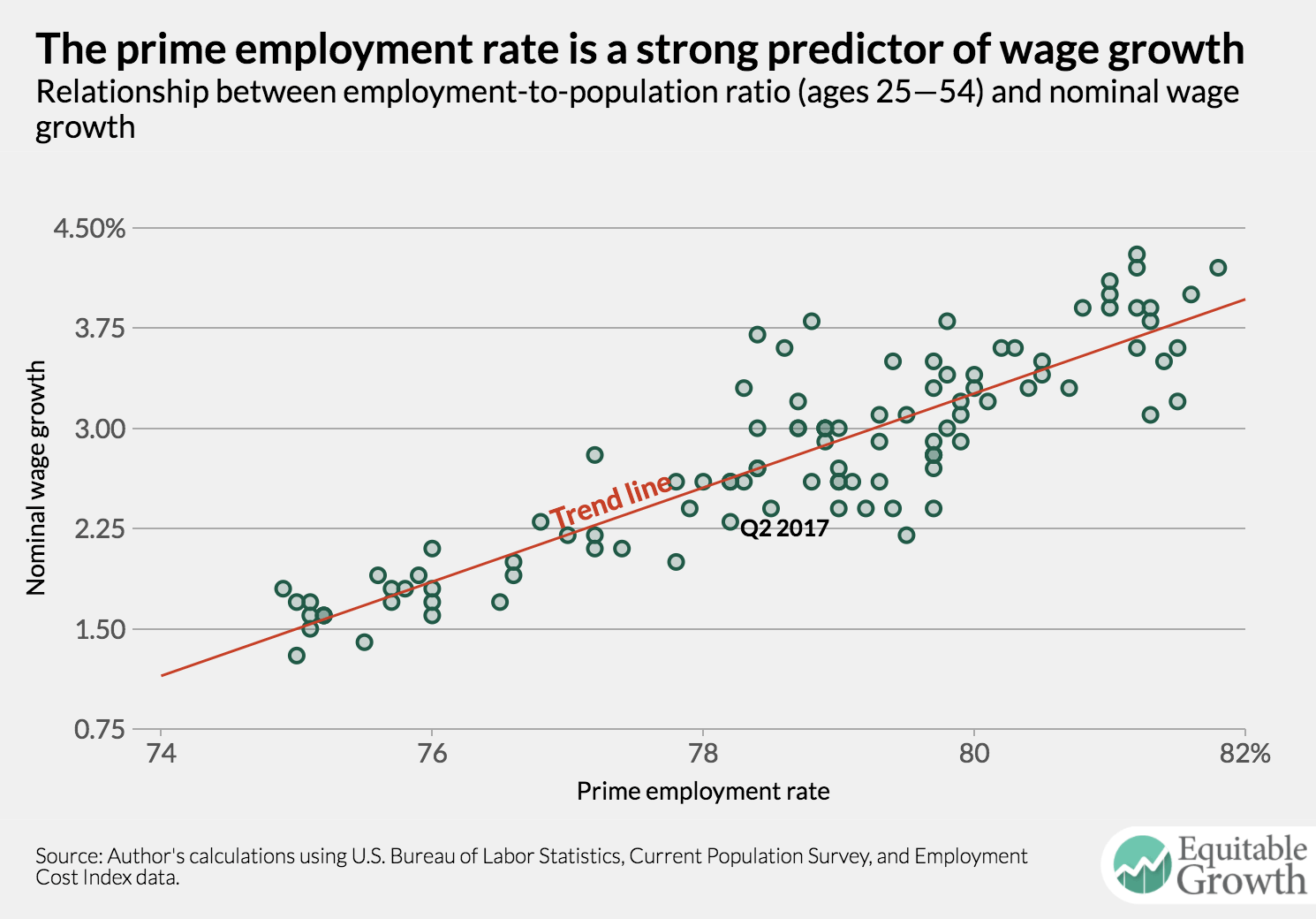

Indeed, the unemployment rate currently does not do a good job of predicting wage growth. What the data show is that a given unemployment rate can be associated with a wide range of wage-growth levels. This issue brief examines, through regression analysis, the strength of the relationships between various measures of labor market slack and wage and compensation growth. The strongest association for wage and compensation growth is with the prime employment rate, the share of workers ages 25 to 54 with a job. This statistic still stands below its pre-recession peak, suggesting the U.S. labor market is not yet at full employment.

The unemployment rate is still a useful measure of the health of the labor market. But it should be taken in the context of other measures. Even if two labor markets have the same unemployment rate, one will be tighter than the other if their employment rates vary significantly. When assessing the health of the labor market, policymakers have to look at both unemployment and employment. If the U.S. labor market still has room to run, then policymakers should look favorably at monetary and fiscal policies that would increase aggregate demand. This information is particularly important for policymakers at the Federal Reserve as they consider the pace at which they raise interest rates.

Measures of labor market tightness

The unemployment rate is by far the most commonly cited labor market statistic. Using responses from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly Current Population Survey, workers are reported as unemployed if they do not have a job and have been actively searching for a job in the recent past. The unemployment rate is the number of officially unemployed workers as a percentage of the total labor force. The labor force is the combined ranks of these unemployed workers and workers with a job.

This is why the unemployment rate is a very appealing measure of the health of the labor market. It’s trying to capture the share of workers who want a job (the labor force) but don’t have one (the unemployed). A declining share of the labor force who are unemployed means a tighter labor market because those who want a job are increasingly finding them. It’s possible, however, that there are many workers who are not actively searching but are willing and able to take a job if they think they can find one. If there is a significant number of these workers, then the unemployment rate could be overestimating the health of the labor market.

A measure of the labor market that doesn’t have to make a judgement call about who is or is not likely to get a job is the prime employment rate. This statistic—better known as the prime-age employment-to-population ratio—is simply the share of the population ages 25 to 54 with a job. It, similar to the unemployment rate, comes from the Current Population Survey. By simply counting a worker as employed or not employed, it avoids the ambiguity of the unemployment rate. Whereas a declining unemployment rate may be due to more workers leaving the labor force, a rising prime employment rate will always mean more workers with a job.

The restriction of only looking at prime-age workers helps eliminate potential biases by looking at all workers. Lower employment rates for younger individuals and older workers are mostly for reasons society looks upon favorably: education and retirement, respectively. Looking at workers in their prime working years means the prime employment rate doesn’t see these positive phenomena as a sign of a weak labor market. Indeed, as the U.S. population ages with the baby boomer generation, more workers will retire and push down the employment rate for all workers. Again, that’s not necessarily an indication of a weakening labor market, while including these workers would bias the employment rate toward underestimating the health of the labor market.

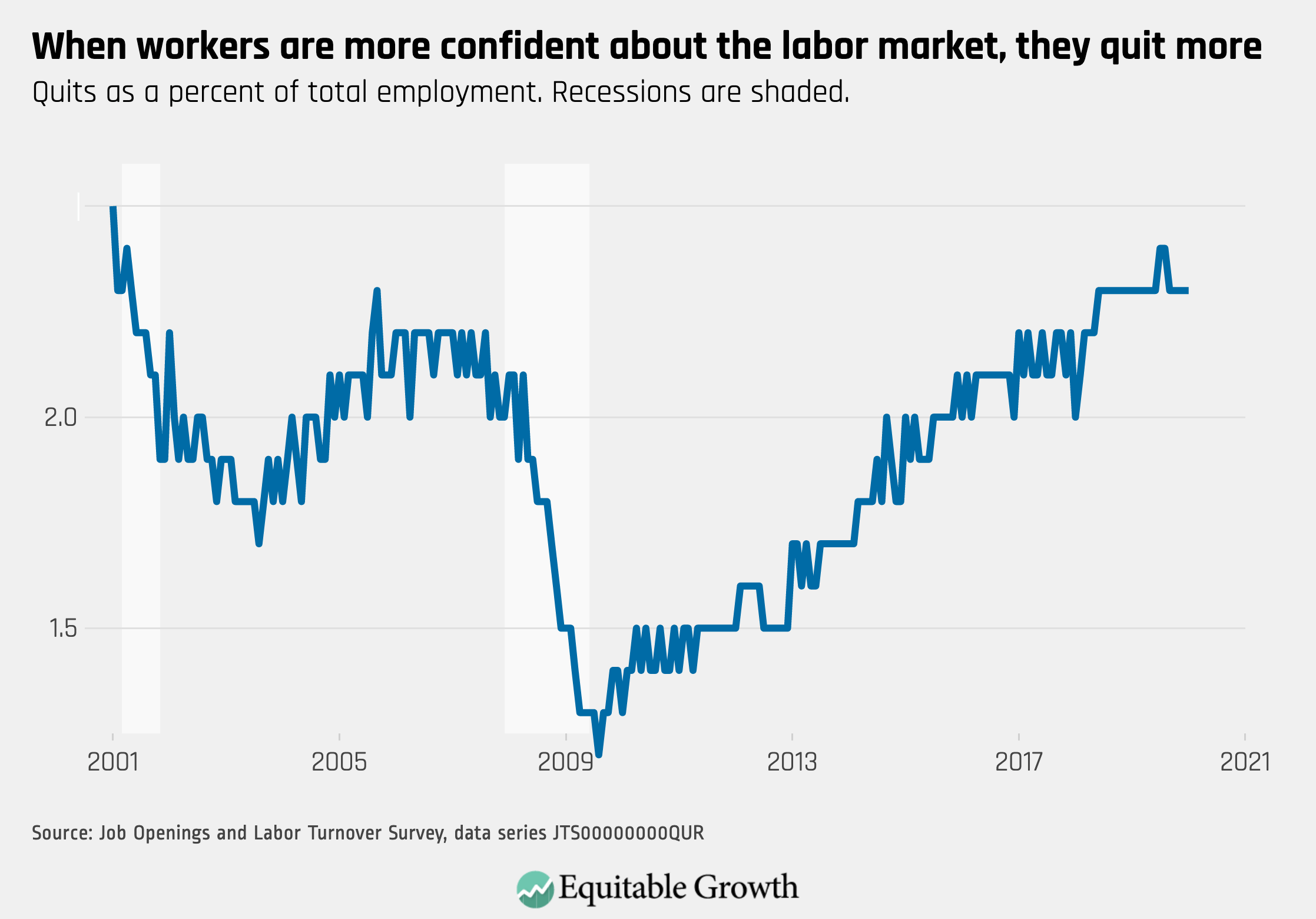

Both the unemployment rate and the prime employment rate are “stock” measures of the labor market. They compare the total pool of employed or unemployed workers to the total pool of potential workers. Compare that to “flow” measures that look at the movement of workers between unemployed and employed, or from job to job. These flow statistics not only help us understand what’s driving changes in the two stock measures. Looking at flows can also tell us, for example, if the unemployment rate is increasing because more workers are moving from employment to unemployment or if it’s because of more flows out of the labor force into unofficial unemployment.

A particularly useful group of flow measures is the statistics that capture the movement of workers between jobs. An employment rate can tell us how many people have a job, but data on job switching tell us how frequently already-employed workers are moving to new jobs. Job switching moves with the health of the labor market. As the labor market strengths, employers will poach employees from other firms, adding to the amount of job switching. As more already-employed workers switch jobs, unemployed workers are likely to be hired. But because data on job switching only directly looks at the already employed, it’s useful to think about this measure as showing the tightness of the labor market for already-employed workers. The Job-to-Job Flows (J2J) data from the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics complied by the U.S. Census Bureau is a good source for job switching data.

Measures of wage growth

Before we can determine which labor market indicator can best predict wage growth, we need to decide on what measure of wage growth to use. The most commonly cited measure of wage growth is the average hourly earnings series from the monthly Current Employment Statistics survey. This series measures the average hourly wage rate for workers using data from the payroll of their employers. This means the data are only for cash wages and do not include other forms of compensation such as employer-provided health insurance or employer contributions to retirement savings vehicles such as 401(k) plans.

The lack of coverage of other forms of compensation might be a concern for using the average hourly earnings series, as nonwage compensation has become a larger share of total compensation in recent decades. A data series that had comparable data for both wage growth and compensation growth would be quite useful. Alas, the Current Employment Statistics series only looks at wages.

Another potential issue with average hourly earnings is that it does not adjust for the composition of workers. Why would this matter? Consider the changes in demographics of the workforce. Let’s say a lot of jobs that are created during an economic recovery go to younger workers, who tend to get jobs in occupations with lower wages. The growth of the average wage would be reduced, as the average wage gets pushed down by the addition of these new jobs. Yet there could be stronger wage growth within occupations that gets washed out by the changes in worker composition. Again, the average hourly earnings data from the Current Employment Statistics series does not adjust for composition.

Luckily, though, data from the Employment Cost Index overcomes these limitations. The dataset has series for both wages and total compensation, and adjusts for the compensation of the workforce. But one downside to the series is that these data are released on a quarterly basis, so they are updated less frequently than the monthly Current Employment Survey. In this analysis, we will use the series that cover only private-sector workers.

Another question is whether wage and compensation growth should be adjusted for inflation or left in nominal terms. The argument for keeping the wage and compensation in nominal terms notes that changes in inflation that seemingly change wage growth may be transitory in the short-term. But workers care about how much their wages will be able to purchase in the future, so adjusting for inflation also makes sense. This analysis will present results for both nominal series and series adjusted for consumers’ expectations of future inflation, using data from the Survey of Consumers by the University of Michigan.

What measures best predict wage and compensation growth?

The analysis in this issue brief uses two ways of seeing how well various labor market statistics can predict wage and compensation growth. Both involve running what’s known as an Ordinary Least Squares regression analysis on the data to calculate a linear relationship between the labor market statistics and wage or compensation growth. First, the analysis looks at how much of the variation in wage and compensation growth each labor market statistic can explain on its own. Second, the exercise shows how much explanatory power each statistic has when tested in conjunction with other statistics.

A fuller description of the analysis is below, but the results are quite clear. The prime employment rate is the single strongest predictor of wage and compensation growth, both in nominal and inflation-adjusted terms. This is true both when looking at a period starting in the early 1990s, covering the past three expansions, or in early 2000s, covering the past two. When all three variables are included in a regression, a percentage point increase in the prime employment rate is associated with a larger or at least as large an increase in wage or compensation growth as the other two variables.

First, let’s run through the results for the explanatory power of each individual labor market statistic. From the end of the 1991 recession until the second quarter of 2017, the prime employment rate explains about 80 percent of the variation in nominal wage growth, about 52 percent of variation in nominal compensation growth, roughly 60 percent of variation in wages adjusted for inflation expectations, and about 43 percent for adjusted compensation growth.

Compare that to the results for the unemployment rate during that same time period. It explains 50 percent of the variation in nominal wage growth, about 25 percent of variation in nominal compensation growth, roughly 37 percent of variation in wages adjusted for inflationary expectations, and about 22 percent for adjusted compensation growth. (For full results of the regressions covering this time period, see Table 1 in the Online Appendix.)

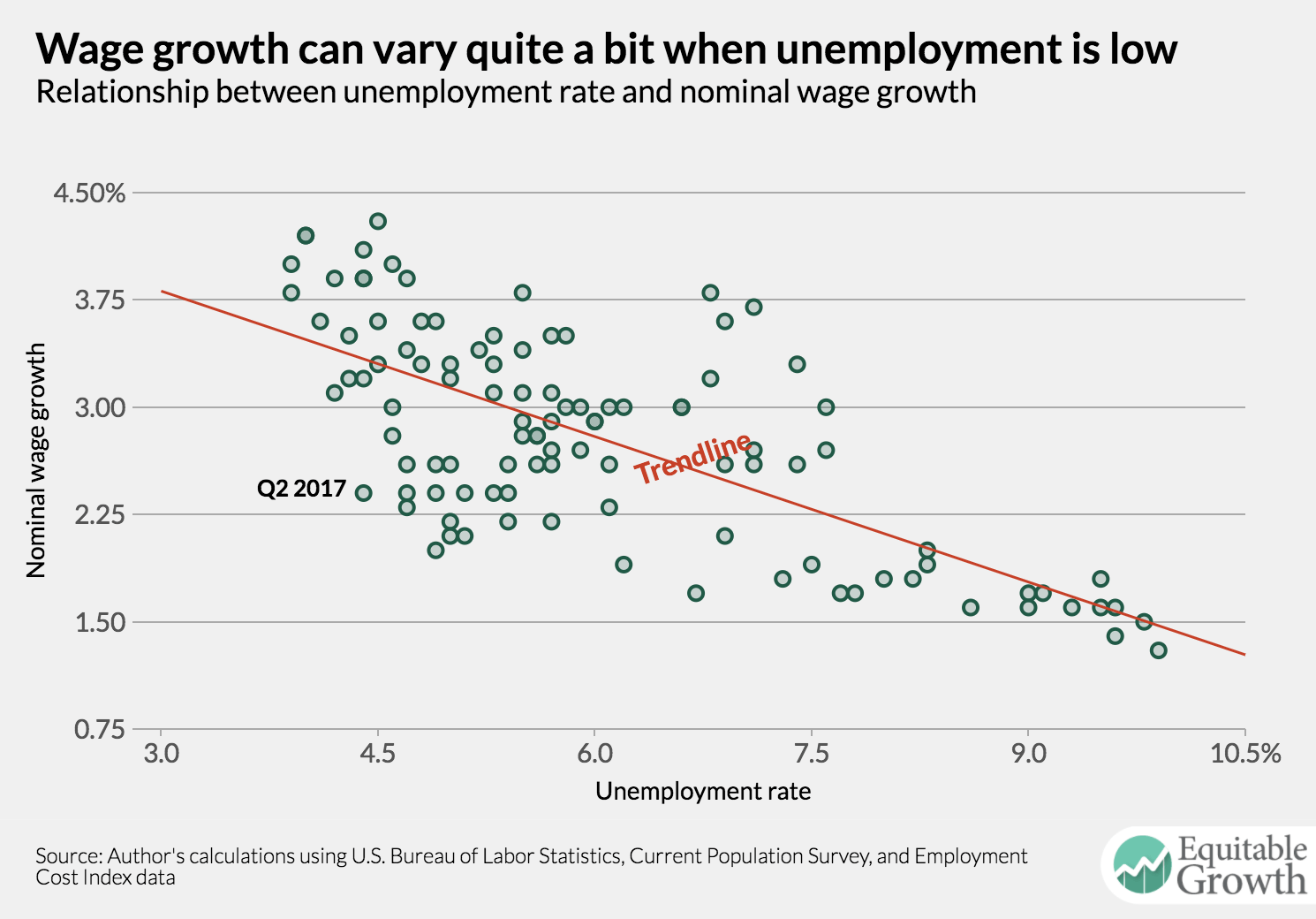

Figures 1 and 2 below show the relative predictive power of the two different statistics. Figure 1 looks at the relationship between the unemployment rate and nominal wage growth. Not only are the dots spread farther apart, indicating a weak relationship, but the most recent data (the second quarter of 2017) also show wage growth is much lower than would be expected from the historical relationship (the red trend line). Using the trend line, we would have expected 3.2 percent nominal wage growth in the second quarter of 2017 with a 4.4 percent unemployment rate. In reality, wage growth was 2.4 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

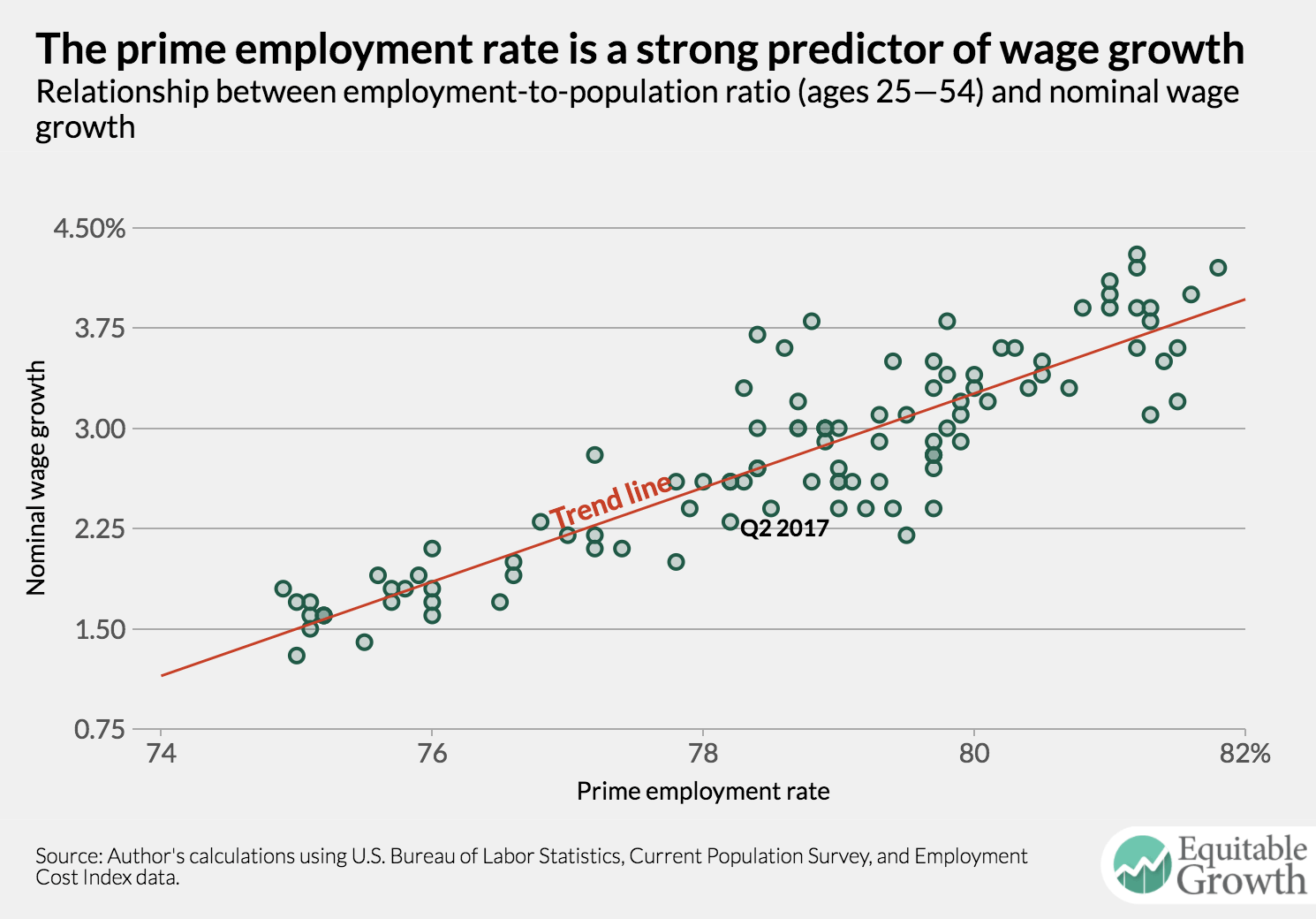

Figure 2 shows much tighter plots for the prime employment rate and a much smaller difference between the actual most recent data and the prediction from the trend line. We would have expected 2.7 percent nominal wage growth using the prime employment rate as a predictor, which was close to the 2.4 percent of reality. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

When we restrict the time period for which we have data from the J2J data (the second quarter of 2000 until the fourth quarter of 2015), the prime employment rate still explains the most variation. For nominal wages, the prime employment rate explains 85 percent, the unemployment rate explains 65 percent, and the job-switching rate explains 67 percent. For inflation-adjusted compensation, the prime employment rate explains 50 percent, the unemployment rate explains 31 percent, and job switching explains 37 percent.

As Tables 3 and 4 in the appendix show, when all three labor market statistics are included in the analysis, the prime employment rate is associated with the strongest increase in wage or compensation growth. Models that include both the unemployment rate and the job switching rate explain less of the variation in wage or compensation growth than the prime employment rate by itself. Interestingly, the job-switching rate seems to have about the same explanatory power as the unemployment rate, with job switching explaining more of the variation in several regressions. (See the Online Appendix for more details on the results from the regressions used in this analysis.)

The results for the unemployment rate are particularly interesting in these regressions. When unemployment is included with the prime employment rate, an increase in the unemployment rate is associated with an increase in wage and compensation growth—the opposite of what we might expect. By including the prime employment rate, these regressions are calculating the relationship between wage and compensation growth and the unemployment rate for a given prime employment rate. In other words, it’s asking how wage growth would change if the unemployment rate went up or down while the prime employment rate stayed the same.

The only way for the unemployment rate to change while the overall employment rate is constant is for either a shift of workers into the labor force from unemployment or from unemployment to out of the labor force. An increase in the unemployment rate in this case would be due to more workers joining the ranks of the officially unemployed, most likely because they are feeling optimistic about the chances of getting a job. In the flip case, a decline in the unemployment rate would be due to flows from unemployment out of the overall labor force. The association with wage and compensation growth makes more sense in this interpretation. (Though, of course, this analysis uses the prime employment rate, so there could be something else going on here. But regressions using the unemployment rate for workers ages 25 to 54 also show a positive relationship). A rising unemployment rate with a constant employment rate would likely be a sign of more labor market optimism—and conversely, a declining unemployment rate in that situation probably indicates pessimism.

Implications

The analysis in this issue brief demonstrates that the U.S. labor market is not as tight as the unemployment rate would have us believe. While this analysis does not directly look at the possibility of workers moving into the labor force, the strong relationship between the prime employment rate and several measures of wage and compensation growth suggest a number of nonemployed workers who can and may find a job are not being counted in the unemployment rate.

As of the third quarter of 2017, the prime employment rate was 78.7 percent. The level of the employment rate associated with a nominal wage growth of 3 percent—the lowest level that could reasonably be called healthy—is 79.2 percent. It would take roughly six more months to get to that level if the prime employment rate grows at the same rate as the previous year. And that would only get the labor market to the lower edge of acceptable nominal wage growth. The labor market does not yet appear to be at full employment.

Many workers who seem locked out of the labor force may, in fact, be able to get a job if the labor market continues to tighten. Research by University of California, Berkeley economist Danny Yagan finds that about three-fourths of the decline in the age-adjusted employment rate was caused by the still-reverberating shocks from the Great Recession of 2007–2009. It’s possible that these shocks can be reversed by increasing labor demand via monetary or fiscal policy, bringing workers back into the labor force. Overestimating the strength of the labor market and leaving these workers unemployed would be a tragedy not only for those workers, but for the U.S. economy as a whole.