This is not a drill. The infections and deaths from the new coronavirus are climbing rapidly. Public events that bring us together are being cancelled or postponed every day to protect our public health—March Madness, NBA and NHL and MLB games, the St. Patrick’s Day Parade in Chicago, South by Southwest in Austin, and counting. Stock prices plunged again yesterday and were down more than 25 percent from their peak in February. More than $5.5 trillion in household wealth has been erased in only three weeks.

For everyone—especially those who had finally gotten a job—the end of the decade-long economic expansion is a financial tragedy. This month and in the months to come, the incomes of families across the country will fall, making it impossible for some to make ends meet. As a result, spending will fall, hitting the bottom line hard at restaurants, car dealerships, construction companies, and many more. State and local governments will see their revenues dry up, while demands on their social safety net programs surge. State balanced-budget requirements could force a choice between fighting the public health crisis or supporting people in financial crisis.

Bold action from federal policymakers is urgent. Policymakers had advance notice about the new coronavirus, and they did not act. Likewise, they had early warnings of the financial crisis in 2008. People saw the dark clouds gathering. They knew that the music was about to stop. Policymakers, if they had listened, had a chance to act before the Great Recession began. They knew mortgage debt was historically high relative to household income, even before house prices began to decline in 2006. They knew that people were quickly losing confidence in the U.S. economy. Policymakers did not act with urgency. They are repeating that grave mistake today. People will suffer again.

Policymakers have no excuse. We had the unfortunate experience of watching people suffer over a decade ago, first as the housing markets unraveled, then as the financial markets went into free fall, and then as the Great Recession took hold. Fiscal stimulus then was too late, too little, and cut off too soon. Bad policy hurt families then and cast a long shadow into the future.

The thin silver lining for the economic threats we face today is that we know how to fight a recession. We know what economic policies will work. Recession Ready: Fiscal Policies to Stabilize the American Economy, a book recently published by the Hamilton Project at The Brookings Institution and the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, is full of policies to fight a coronavirus recession that will work. The polices are backed by evidence, cutting-edge research, and lived experience.

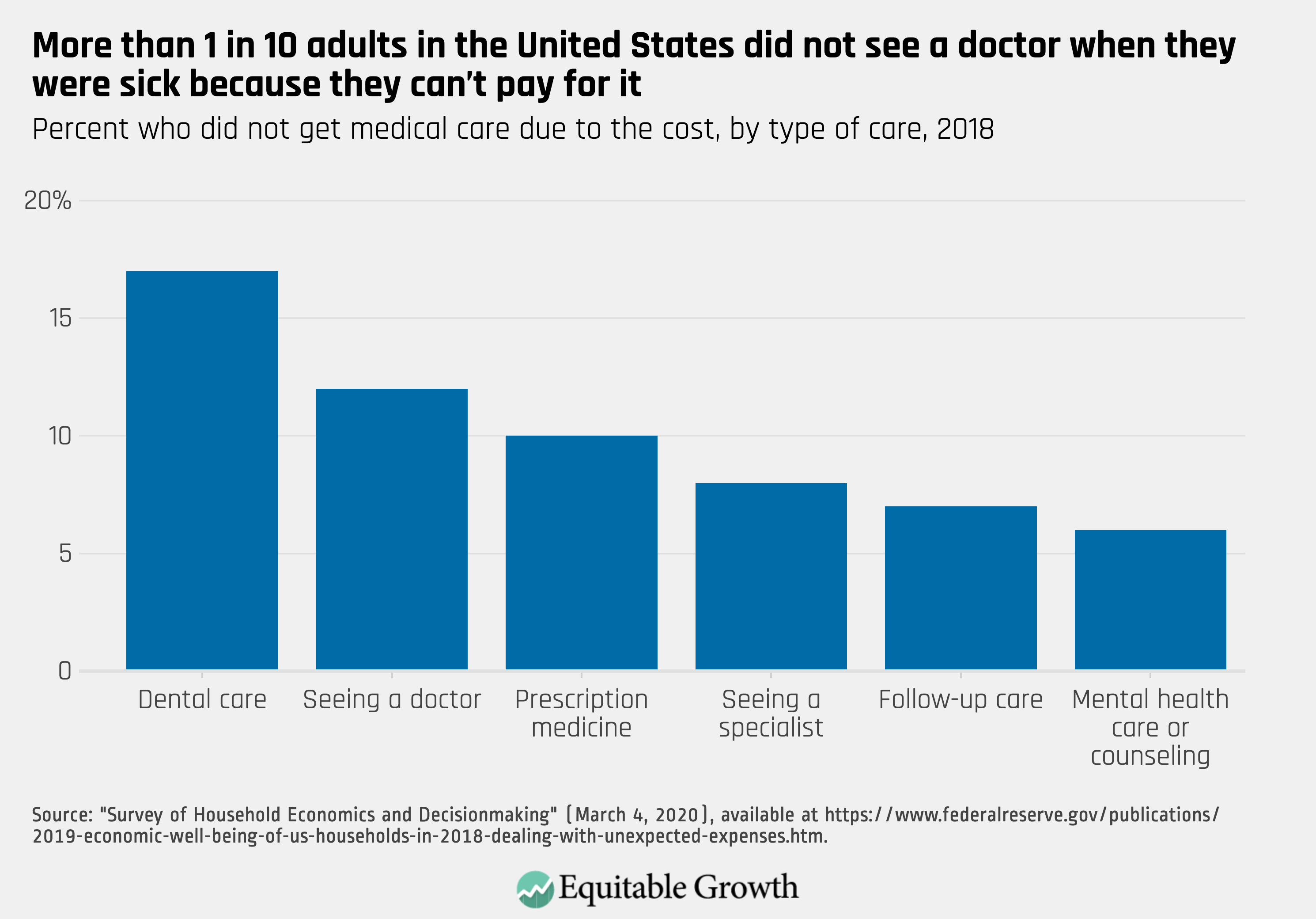

U.S. policymakers need to act now, go big, and tell people that the federal government has their backs. The government must fight the new coronavirus, and it must fight for people. Above all, it must fight for the families who cannot fend for themselves. Things will get worse in the weeks ahead. Families will suffer, especially workers in low-wage industries, families without health insurance, the people doing gig work, and everyone else who remains marginalized across the U.S. economy.

Democrats in the U.S. Congress proposed legislation earlier this week that would fight back. It would support those directly affected by the new coronavirus and those most vulnerable to its many threats. This support is essential. Everyone—from those who cannot afford the medical tests to those who cannot afford to miss work—needs direct, comprehensive help. We must fund these efforts with hundreds of billions of dollars.

The Trump administration has discussed a large cut in payroll taxes for the rest of the year. The president is right to go big, but he needs to go better. A payroll tax cut won’t do it. It will be too slow and its effects too small—so small, most won’t even notice it. Those who don’t have or will lose their jobs won’t get it at all. Most importantly, workers with high incomes will receive the most money. They don’t need it. We need to help people who do. The payroll tax cut is bad policy. We know its shortcomings from the Great Recession. We must not repeat that mistake.

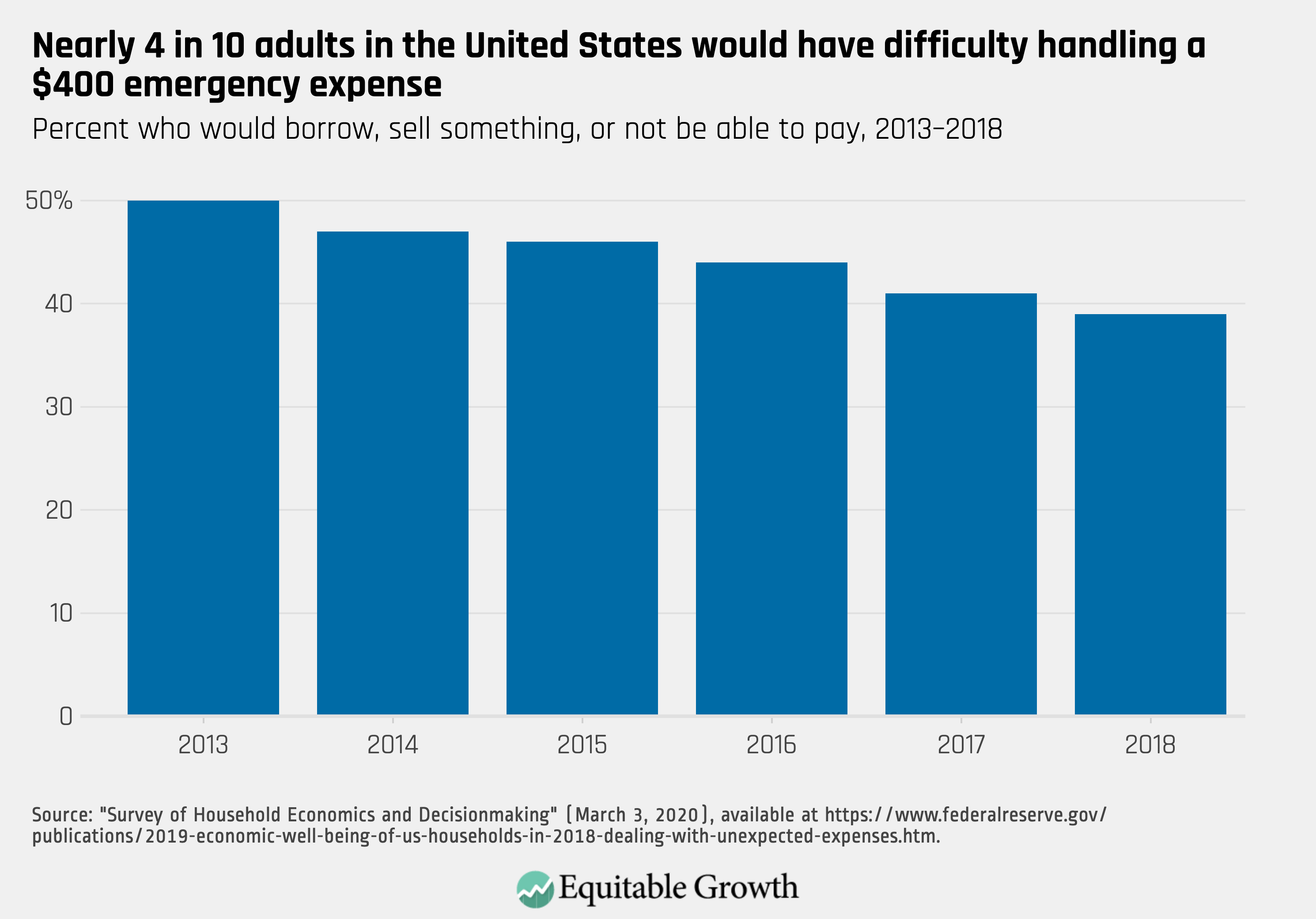

We can do so much better than the administration’s payroll tax cut. We absolutely must get a lot of money to families if the new coronavirus affects them directly. But that is not enough. We need to send money to everyone now. People do not know today if they are going get the coronavirus, miss a paycheck, or lose their job. All these outcomes were unthinkable a month ago. Now, they are real. People are scared. They need a financial cushion right now, and many do not have one. They need some extra money.

Policymakers can deliver, and they must. One effective way is to eliminate the first $500 of withholding for federal income taxes and Social Security payroll taxes for workers in April, May, and June. This policy would increase take-home pay by $500 per month. This novel approach would get money in people’s pockets within weeks. Congress and the Trump administration can do this, and it will work.

Money to all workers is only a front line not a battle plan for a coronavirus recession. We need much more aggressive and durable support for families without breadwinners in the workforce who suffer the most during recessions. That support will require far more than $500 a month in paychecks and more than our current safety net programs offer. We need additional comprehensive social supports. Protections for workers, individuals, and small businesses are grossly insufficient in the United States, and many families cannot handle any drop in income.

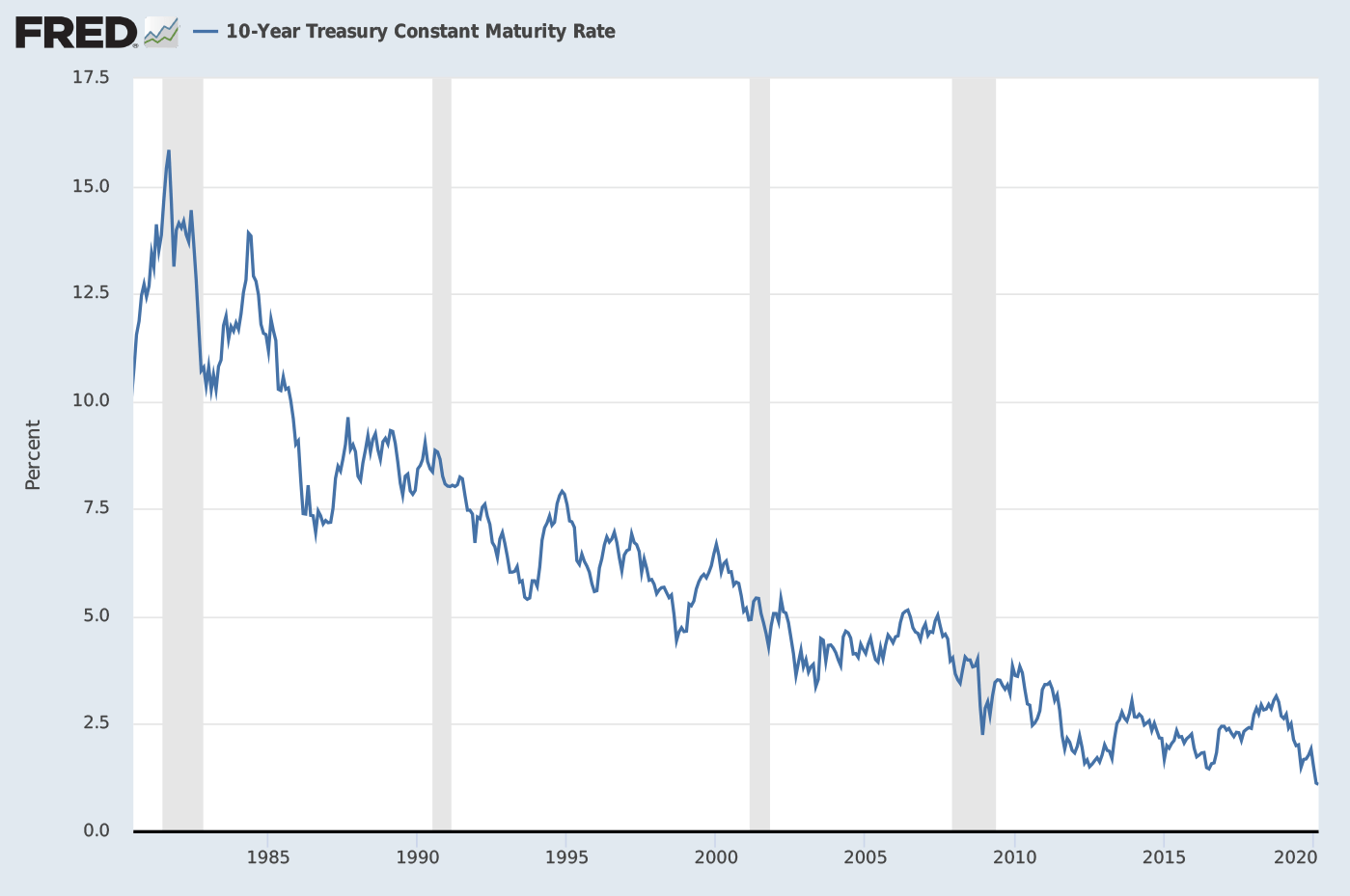

Both Democrats in Congress and the president want paid sick leave. Moreover, Democrats have proposed commonsense paid family leave, free medical testing, and other aid that recognizes just how little a buffer most families have to weather this recession. The investment by the federal government in people is worth it, both from a moral perspective and an economic perspective. Today, with the cost of borrowing at historic lows for the federal government, it is also an ideal time to do so.

Perhaps most importantly, we need to enact long-lasting policies that make the U.S. economy more resilient in the years to come. Luckily, we know what works. Economists have studied the previous recession and arrived at a set of policy recommendations in Recession Ready that will make our economy stronger and nimbler when the next crisis hits. Each one was used in the Great Recession and worked. Policymakers can improve upon these programs by making them start automatically when economic indicators say a recession is coming. And those programs will stay in place until people and businesses are back on their feet.

Fight the new coronavirus today. Get automatic stabilizers that always fight a recession in place for the future. Policymakers in the nation’s capital must go deep and wide. They must go now.