Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Jonathan Sallet has authored this month’s contribution.

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

Between September 2018 and June 2019, the Federal Trade Commission conducted a series of public hearings to study the landscape of competition and consumer protection. The next step—and the crucial one—is for the FTC to integrate the lessons learned from those proceedings into its day-to-day work.

Here are five building blocks for successful antitrust enforcement that the FTC should embrace in order to, as its Chairman Joseph Simons said (quoting his predecessor Bob Pitofsky), “restore the tradition of linking law enforcement with a continuing review of economic conditions to ensure that the laws make sense in light of contemporary competitive conditions.”1

Antitrust enforcers should pay attention to growing market concentration

On the first day of the hearings, Jonathan Baker, a law professor at American University’s Washington School of Law and author of the new, indispensable book The Antitrust Paradigm, laid out nine reasons to conclude that “market power is substantial and has been growing.”2 Baker emphasized that the growth of oligopolies in markets that include airlines, brewing, and hospitals are all outcomes that he said cannot be explained simply by growth in scale economies.3

Economists Joshua Wright at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia School of Law and Steven Berry at Yale University took different views. Wright said that his review of the evidence of market concentration led to the conclusion that “we do not know much that is relevant to formation of antitrust policy” and emphasized that he would not equate market concentration with the presence or absence of competition.4 Berry cautioned against overreliance on market concentration as the explanation of the increase in corporate profits.5

But Berry also emphasized that in light of the evidence of higher markups, “[w]e cannot just wave our hands and say it is all fine.”6 Rather, he said that “sophisticated context-sensitive antitrust policy is clearly important.”

What to do in the face of these competing viewpoints? In her testimony that same day, economist Fiona Scott Morton at the Yale University School of Management emphasized that uncertainty does not justify antitrust inaction. Rather, she said that the evidence of growing market power suggests that underenforcement is today a greater risk than overenforcement.7

Underenforcement can lead, of course, to familiar kinds of competitive harm, such as higher prices and reduced innovation. But there is more. The United States is in its fifth decade of increasing income inequality—on September 26, 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau released figures showing that income inequality had reached its highest level in more than 50 years of measurement. Baker and Steven Salop at Georgetown Law opined that “[m]arket power contributes to growing inequality.”

Scott Morton’s point is fundamental. Antitrust is law enforcement, and law enforcement rests on case-specific evidence. But larger trends should surely impact the prioritization of antitrust resources and the questions that antitrust enforcers ask. Indeed, if the right investigations are not opened and the right questions are not asked, then we may never know whether a problem ever existed.

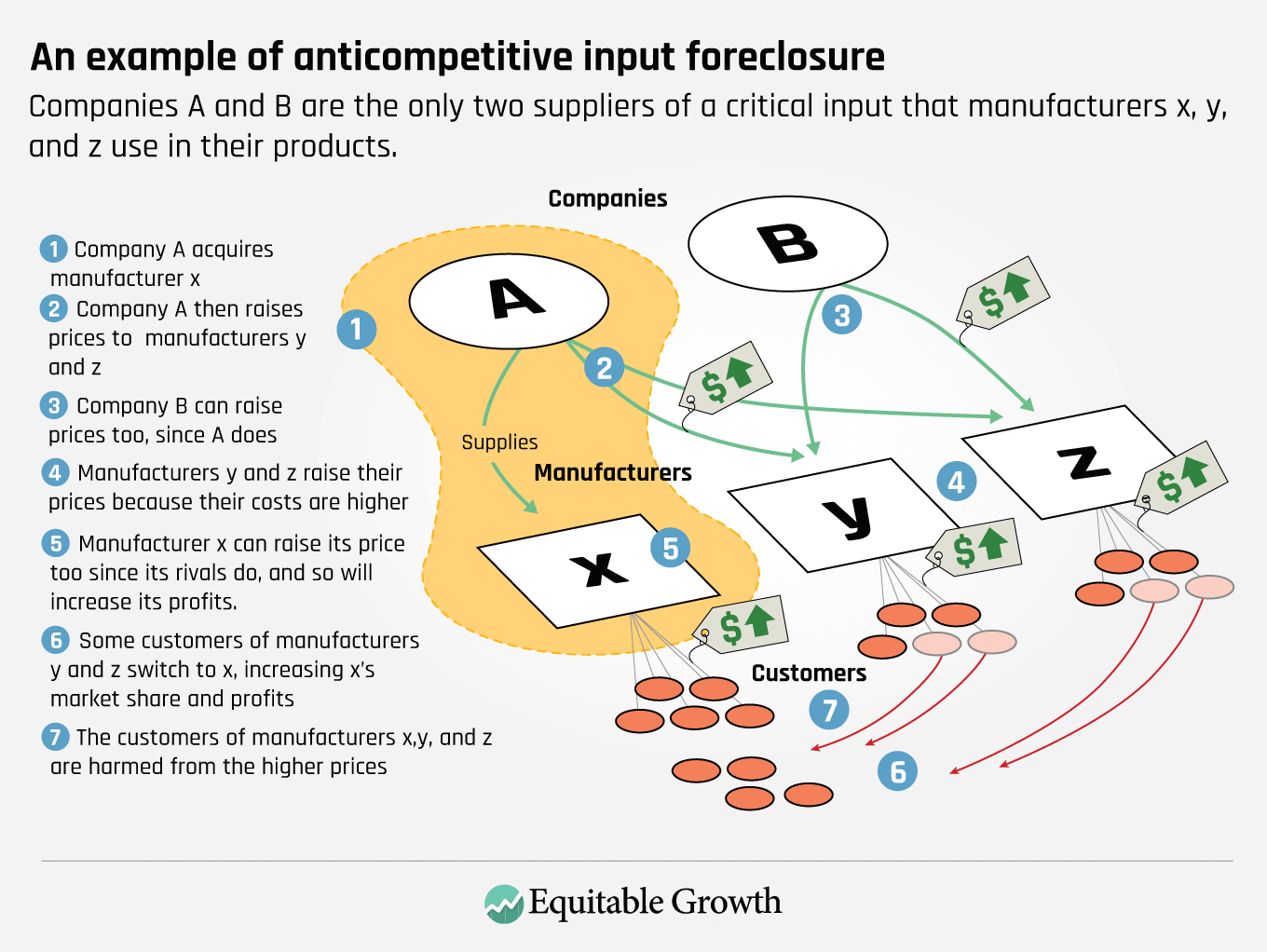

Vertical merger transactions are a good example. As Salop explained at the hearings, vertical mergers may look benign in a world of unconcentrated upstream and downstream markets, where customers at both levels face a plethora of competitive alternatives, but such transactions require much greater scrutiny when a new vertical relationship is created in a world of oligopolies. 8 That’s because the existence of oligopolies make it more likely that an input supplier can harm some of its customers in order to aid its downstream affiliate and harm consumers as a result. Salop argued that anticompetitive presumptions should apply to vertical mergers in some circumstances.

Daniel O’Brien, former deputy director of the FTC’s Bureau of Economics and now executive vice president at the consultancy firm Compass Lexecon, didn’t see it the same way. He told the commission that he did not contend there could never be input foreclosure, but contended that mergers of companies offering complementary products would normally be procompetitive.9 An example of complementary products would be razors and razor blades—if you use one, you’re more likely to use the other. O’Brien also said that procompetitive presumptions should apply to some vertical mergers.

In my view, the discussion of vertical mergers illuminates why antitrust enforcement should recognize the changing nature of markets and, in particular, the manner in which the existence of oligopolies increases the need to consider theories of harm when considering vertical arrangements. Understanding broad changes in the U.S. economy helps antitrust agencies formulate theories of harm, focus their economic analysis, and consider, early on in an investigation, what facts will likely be most important. The forthcoming FTC competition report should consider how best to recognize the implications of these broad economic trends.

Business models are evolving, which can change the terms of competition

Two-sided business models aren’t new. Think of the coffee house in London in the early 1700s that, profiting from the aggregation of ship owners and the insurance brokers, morphed into Lloyd’s of London. But today, multisided business models intersect with other economic trends that include network effects, the aggregation of data, and vertical integration. That’s a reason why merger enforcement should look more closely at the acquisition of potential or nascent competitors.

If Microsoft Corp. in the early 1990s had tried to buy the then-independent web browser company Netscape in order to protect its monopoly in personal computer operating systems, would enforcers have then understood the competitive implications of blunting the ability of new browser rivals to attack the market for PC operating systems? Such potential or nascent competition is particularly important in winner-take-all markets that often (and without any necessary trace of anticompetitive conduct) tip toward single-firm dominance—an outcome that emphasizes competition for the market, not just competition for greater share within a market. When dominance becomes embedded, markets are much less likely to self-correct.

Also, antitrust enforcement should fight any extension of the U.S. Supreme Court opinion in Ohio vs American Express Co. (wrongly decided in my view) to multisided business models generally. Any expansion of American Express would leave consumers and competitors vulnerable to a range of anticompetitive actions that are justified by a company sharing its increased profits with one out-of-market group of users at the expense of others.

The American Express decision paired this error with another one—the suggestion that direct evidence of harm to competition isn’t enough in an vertical case without the separate presentation of a properly defined antitrust market. The forthcoming FTC competition report could usefully untangle these knots by explaining how to identify the narrow slice of multisided markets actually at issue in American Express, and then offering thoughts on how to identify competitive harm in vertical cases generally.

Antitrust enforcement protects competition, not just consumers who buy things

Multiple speakers explained that antitrust protects the competitive process, not just direct purchasers or final consumers. Carl Shapiro, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, proposed in the hearings that a business practice be judged to be anticompetitive if it harms trading parties on the other side of the market as a result of disrupting the competitive process.10 For Shapiro, this approach would give structure to antitrust law and economics in a world in which the dangers of horizontal agreements, exclusionary conduct, and anticompetitive horizontal and vertical mergers have all grown.11

Think about the potential impact on workers from the market power of employers. University of Pennsylvania economist Ioana Marinescu proposed in her work, including with UPenn Law School professor Herbert Hovenkamp, that when merging employers in the same place hire workers with the same kinds of qualifications to do the same kind of job, traditional antitrust principles appropriately ask whether the workers would be harmed by a labor monopsony.

The extent to which labor monopsonies are generally the cause of lower wages for workers was hotly debated. Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Nancy Rose, for example, questioned whether market concentration is generally the cause of low wages. At the same time, she recommended the study by Elena Prager at Northwestern University and Matt Schmitt at the University of California, Los Angles of hospital merger effects on labor as the type of study that can shed light on this question. And enforcement activity has recognized circumstances, concerning nurses and Silicon Valley workers for example, in which antitrust injury has been inflicted upon employees.

That recognition is the basis, for example, for the joint 2016 Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission policy treating as illegal “no poach” agreements among companies not to hire each other’s workers. Similarly, in United States v. Anthem, Inc., the Department of Justice challenged a healthcare merger asserting, in part, that the increased buyer power of the new firm would “enhance Anthem’s leverage,” which would likely reduce the rates that hospitals and physicians would be able to earn.

So, there appears to be a broad consensus that merging employers could hold market power over labor and that where that would occur, the transaction should be examined using well-established antitrust principles.

Indeed, monopsony, as a concept generally, deserves more attention. Monopsony is monopoly turned upside down—with market power being directed by a buyer at a seller to force input prices artificially lower than they would be in a competitive market. As the Supreme Court said a long time ago, antitrust enforcement is not just about protecting consumers from rising prices but also about guarding more broadly against anticompetitive disruption of competitive pricing (and nonpricing terms).12 That understanding reaches monopsonies, too.

Another example of antitrust enforcement ensuring competition arises when harm is to a business, not directly to a consumer. For example, the FTC successfully blocked the proposed Staples-Office Depot merger that would have harmed business customers. The FTC should not narrow its search for competitive harm to consumers only.

Modern economic analysis is up to the challenge

Of course, knowing more is always better than knowing less. But law enforcement agencies need to make the best judgements they can because justice delayed is justice denied. So, it’s important to recognize that modern economics offers analysis fit for these times. As Scott Morton said at the FTC hearings, “I think we have the tools. I do not think we need to spend ten years developing the tools.”13

Indeed, in 2018, Scott Morton wrote, along with Jonathan Baker and me in the Yale Law Journal, that in the aftermath of the Chicago School critique of antitrust enforcement, the economics profession has developed “many tools that identify and measure anticompetitive conduct.” Economics can now explain why it does not make sense to presume that markets will self-correct from monopoly or collusion, exclusionary vertical conduct cannot be anticompetitive because there is only a single monopoly profit, or most mergers in concentrated markets are efficient and therefore procompetitive. The FTC hearings featured important perspectives on the best way that antitrust agencies can apply today’s economic learnings in a manner that ensures that antitrust fully recognizes today’s competitive conditions.

Congress gave the FTC broader enforcement tools than just the Sherman and Clayton Acts

An important aspect of Federal Trade Commission authority is the scope of Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914, which establishes the agency’s power to halt “unfair methods of competition.” I suggested at one hearing that Section 5 should be re-examined and applied to reach anticompetitive harms beyond the reach of the Sherman Act. This might include unilateral conduct that, as Steven Salop has written, “leads to achievement, maintenance, or enhancement of market power that likely harms consumers on balance.”

In its administrative complaint filed against Intel Corp., for example, the FTC alleged that Intel’s conduct constituted a “stand-alone” violation of Section 5 (that is, without reference to the Sherman Act). UPenn’s Hovenkamp has suggested that the FTC consider the use of Section 5 to attack monopoly in its incipiency, reach collusion-like activity (including through the use of certain most-favored nation clauses), and halt anticompetitive behavior outside a firm’s primary market, where these is no actionable threat of achieving market power in that other market.

So, for example, the FTC commissioners could consider whether input foreclosure is harmful to competition when conducted by an integrated firm with market power in a concentrated market for the production of a critical input where its upstream affiliate (the supplier of that input) is a substantial supplier of that input to downstream rivals.

After all, the FTC was given its authority in 1914 under the Federal Trade Commission Act precisely because Congress decided that the Sherman Act didn’t go far enough. Similarly, although the FTC’s Section 5 prohibition of “unfair and deceptive acts and practices” has traditionally been applied to consumer protection issues that are separate from competition questions, the agency should be alert to circumstances in which anticompetitive conduct is also unfair and deceptive. Imagine false statements by a seller to consumers that effectively prevent rivals from competing effectively to the detriment of those consumers.

Conclusion

These five lessons should inform the full spectrum of the FTC’s competition work, from framing the issues to be examined in a merger or conduct investigation to creation of remedies, the use of rulemaking authority, and competition advocacy. These five lessons also should apply to litigation, the ultimate test for antitrust enforcement. And they should also help generalist judges understand what antitrust law and economics have already established.

As the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s Director of Markets and Competition Policy Michael Kades explains, government antitrust enforcement is hampered when courts require antitrust enforcers to spend their time and resources proving water makes things wet rather than bringing cases on behalf of consumers.

This is the moment when the FTC can again demonstrate the intellectual curiosity that was the basis for its creation—as an expert agency that rigorously analyzes markets and competition. The FTC’s competition hearings provide both a map for antitrust enforcement and a benchmark against which to measure future administrative and judicial decisions. Publication of a strong, pro-enforcement report and the integration of its learnings into the day-to-day work of the FTC will be an important and necessary step in the right direction.

—Jonathan Sallet is a senior fellow at the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society. I am appreciative to Jonathan Baker, Michael Kades, Steven Salop, Carl Shapiro, and Fiona Scott Morton for their review of this essay in draft form.