A Canary in the Coal Mine for the Failure of U.S. Competition Law: Competition Problems in Prescription Drug Market

Michael Kades

Director, Markets and Competition Policy, Washington Center for Equitable Growth

Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights:

Prescription for Change: Cracking Down on Anticompetitive Conduct in Prescription Drug Markets

July 13, 2021

Thank you, Chairwoman Klobuchar and Ranking Member Lee, for the opportunity to testify about the critical issues of competition and prescription drug markets. Antitrust is, to quote Sen. Klobuchar, “cool again.” The president’s executive order signed last Friday and his accompanying remarks are testament that we are in an antitrust moment as dramatic as any since 1914, when Congress passed the Clayton Act and created the Federal Trade Commission.

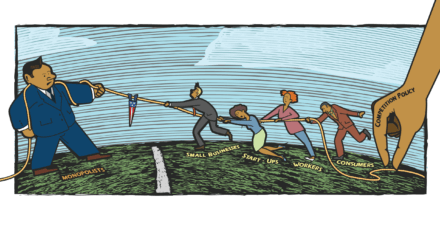

All too often in the press or on social media, competition and monopoly are synonymous with digital platforms. Without doubt, those markets raise important competition issues and deserve the attention that they are receiving. Market power and its abuse, however, extends across the U.S. economy.1 This subcommittee should be commended for its investigation into market problems throughout the economy. The substantial antitrust reform proposals offered by both Chairwoman Klobuchar and Ranking Member Lee, respectively, reflect a judgment that the antitrust laws, as currently interpreted and enforced, are failing to protect competition.

The subcommittee is correct to examine competition in prescription drug markets. Prescription drugs cost nearly $370 billion a year, forcing too many Americans to choose between their health and other necessities. Further, the impact is often borne by those least able to bear it: lower-income Americans and those from historically disadvantaged groups.

It is an important industry, and one that is rife with anticompetitive conduct. Although not the sole cause of high prescription drug costs, abusive practices that distort competition contribute to the problem. Too many companies exclude competition through a variety of anticompetitive tactics, including rebate traps, product hopping, sham litigation, citizen petition abuse, and pay-for-delay patent settlements.

Anticompetitive activity is prevalent for two related reasons. First, the economic dynamics of prescription drug markets make anticompetitive conduct both uniquely effective and profitable. Second, the courts have increasingly stripped the antitrust laws of their potency. As a result, too often, anticompetitive conduct escapes condemnation. Rather than deterring anticompetitive conduct, the antitrust laws, as currently interpreted by the courts, almost invite it.

It would be wrong, however, to think anticompetitive conduct and market power are uniquely a prescription drug market phenomenon. Rather, prescriptions drug markets, where these problems have existed for decades, were the canary in the coal mine. We are seeing similar problems across the economy, including in agricultural markets, digital markets, and labor markets. Although the competitive dynamics and potential anticompetitive conduct differs across industries, one common thread exists. The antitrust laws, as enforced and interpreted, do not sufficiently deter anticompetitive conduct. As the letter to the House Judiciary Committee that I signed with 11 other economists and lawyers explains: “current antitrust doctrines are too limited to protect competition adequately, making it needlessly difficult to stop anticompetitive conduct in digital markets.”2 The same judgment applies to prescription drug markets and many others.

As Equitable Growth’s antitrust transition report explains, “Without new legislation, the agencies can still address these issues, but the task will be more challenging and take far longer.”3 The courts have made it clear that they believe the antitrust laws have, at most, a limited role in protecting competition because the market can fix itself. And, therefore, do no harm is the prevailing approach. Unless Congress takes a different view by passing legislation, dominant firms will have little concern about the antitrust laws limiting their conduct.

For prescription drug markets, there are two broad types of reform. Congress can restore the vitality of antitrust laws generally, which will, when combined with vigorous enforcement, deter much of the anticompetitive conduct occurring in prescription drug markets and in other industries. Current economic research strongly supports such reforms. The Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act would address most of these problems.

Second, certain problems that are unique to pharmaceutical markets may require specific legislation, as the CREATES Act effectively eliminated two specific anticompetitive strategies that delayed lower-cost, generic competition.4 Existing legislation—such as the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act, which addresses pay-for-delay patent settlements; the Stop STALLING Act, which addresses abuse of the Food and Drug Administration’s citizen petition process, and the Affordable Prescriptions for Patients through Promoting Competition Act, which would address product hopping and patent thickets—are examples of this approach.

Stopping anticompetitive conduct has the additional advantage that it is unlikely to deter innovation. As Competition itself drives innovation. In contrast, anticompetitive conduct often spurs rent-seeking activity. In pharmaceutical markets, weak antitrust enforcement may encourage companies to engage in minor product development as a tool to exclude competition.5 Although policy makers should consider the trade-off that can occur between lower costs and promoting innovation, effective antitrust laws should avoid that choice and lead to lower costs and increased innovation.

The remainder of statement discusses why prescription drug costs matter, the nature of competition in these markets, the prevalence of anticompetitive conduct, the failure of antitrust to deter such conduct, and proposals for address these problems.

- Why prescription drug costs matter

In 2019, the United States spent almost $370 billion on prescription drugs, accounting for roughly $1 out of every $10 spent on healthcare.6 Prescription drug costs are not just a pocketbook issue.7 When prescription drugs are unaffordable, it affects the patient, not just her pocketbook. Twenty-nine percent of people report not taking their medicines as prescribed at some point in the past year because of the cost, which rises to 35 percent of people with household incomes of less than $40,000. Across the country, people are making choices about which medicines they can afford or are choosing between life-saving dugs and necessities such as food or rent.8

The burden of prescription drug costs disproportionately affects lower-income Americans and historically disadvantaged groups. Prior to the pandemic, 25 percent of White Americans said they do not take prescriptions due to costs, compared to 30 percent of Black Americans.9 In a 2019 AARP survey, 48 percent of Hispanic/Latinx respondents said they did not fill prescriptions provided by their doctor, the main reason being cost. Twenty-seven percent of Latinx respondents said that they cut back on necessities such as food, fuel, and electricity to be able to afford a prescription drug.10

Prescription drugs fall into two broad categories. The more traditional and common ones are called small molecule drugs (ibuprofen, antibiotics, etc.). A newer but growing category is biologics, which are protein-based and derived from living matter or manufactured in living cells using recombinant DNA biotechnologies (Humira).11 Critically, price competition, whether for small molecule drugs or biologics, comes from a limited set of potential competitors. And the incentives to prevent that competition are large.

- Generic competition for small molecule drugs

The impact of the Hatch-Waxman Act on competition for small molecule drugs cannot be overstated. Prior to its passage, few generics were available. Today, generic competition has a dramatic impact. A generic product, on average, captures 90 percent of the market within a year of entering the market,12 and the branded company’s profits plummet.

Simply delaying generic competition can be very profitable. Generic competition leads to substantial price decreases. Eventually those prices fall to roughly 15 percent of the branded price.13 While generic companies earn profits, the big winners are consumers, who end up receiving the same therapeutic benefit at a far lower cost. Conversely delaying or preenting that competition is profitable for the branded company.

- Biosimilar competition for biologics

Biologics drugs such as Humira represent an increasingly large portion of prescription drug costs. Currently, the biologic market is more than $210 billion.14 They offer great promise in combating debilitating and rare diseases.15 But they tend to be very expensive, costing patients tens, or even hundreds, of thousands of dollars per year.

In biologic markets, price competition to a branded product comes from a biosimilar product. Like generic small molecule products, biosimilars have no clinically meaningful difference from the corresponding biologic drug.16 Biosimilar drugs, however, are more expensive to develop than generic small molecule products, and they require more testing. Experts expect that biosimilar production would be priced at less of a discount and achieve a lower level of market penetration than generic small molecule drugs.17 With many biologics having high prices and large revenues—in 2020, Humira sales exceeded $16 billion18 and Keytruda (an oncology treatment) exceeded $14 billion19—biosimilar competition can save hundreds of millions of dollars per year per drug even if the biosimilar product is priced at a modest discount (25 percent) and gains only a modest share (30 percent).

That competitive dynamic for biosimilars is more complicated than for small molecule generic drugs because there are many decision-makers and overlapping legal and regulatory structures. Successful competition means the product has obtained approval from the Food and Drug Administration, the product has a preferred status on the insurer’s formulary, and a doctor, who has little or no financial incentive, has prescribed it. If competition breaks down at any point in that chain, prescription drug costs increase.

Anticompetitive conduct in prescription drug markets is both prevalent and persistent. Even in areas where antitrust enforcement has had moderate success, such as with pay-for-delay settlements, it has taken more than a decade, the success is fragile, and it requires substantial resources. In other areas, antitrust enforcement has been less successful at stopping anticompetitive conduct at all.

The list of anticompetitive conduct is large; here, I discuss three types of common practices.

- Rebate traps

A rebate trap can effectively deter competition or limit its impact in pharmaceutical markets, particular biologic ones.Pharmaceutical companies give pharmacy benefit managers (companies that manage drug benefits for insurers) rebates for a preferred status on the formulary. It might seem like a larger rebate means lower prices. Sometimes it does, but not always. Facing biosimilar competition, the incumbent company can raise its list price, increase its rebate, and make it dependent on market share (say, 95 percent). If the share of the incumbent biologic falls below that, the PBM receives no rebate and must reimburse the incumbent based on the list price for all units. Alternatively, the incumbent can offer a bundled discount across a range of products, which the new entrant cannot match.

The strategy can harm competition in at least three ways. First, there can be a large installed base. For example, 80 percent of patients are unwilling to switch to a new product because they are on a long-term regime. In principle, a new product should be able to compete for the other 20 percent of the market. Even if the new product is less expensive, however, the PBM may be worse off because it loses the rebate for the 80 percent of the market that will not shift. More generally, particularly with biosimilar products, it may take time for doctors and patients to become comfortable with a new product. Finally, the incumbent could be sharing its monopoly rents with the PBM. The economic theory is well-accepted.20

Questionable rebates are common in prescription drug markets. According to a Senate staff report, rebating “appears to be contributing to both increasing insulin WAC prices and limited uptake of lower-priced products.”21 Mylan Pharmaceuticals used rebating to combat lower-prices competition to its Epipen product, which treats severe allergic reactions. Rebates may also explain why significantly less-expensive biosimilar versions of Remicade had difficulty gaining traction in the market.22

Notably, courts have struggled with this rebate trap. In the Epipen antitrust case, for example, the District Court granted the defendant’s summary judgment motion and dismissed the antitrust case. It did so, even though it agreed that the plaintiff could prove the following at trial: Epipen had a monopoly. Mylan Pharmaceuticals, the manufacturer of Epipen, and Sanofi, the manufacturer of the competing product, both expected Sanofi’s product to gain 30 percent or more of the market within 3 years. Instead, Mylan, through a rebate trap, prevented Sanofi’s success while increasing both Epipen’s net price and profits.23 If proven, those facts are the very definition of exclusionary conduct.

- Product hopping

Product hopping is another anticompetitive tactic used to prevent or delay competition. A brandedcompany makes a small change to its product shortly before a generic competitor enters. For example, the new product might be a different form of the medication (switching from tablet to capsule), different dose, or a once-a-day version of the product. It then takes a range of actions to move the franchise from the old product to the new, tweaked product. At the most aggressive, it can withdraw the original product from the market. Less draconian tactics can be just as effective. The company could increase the price of the original product well above the price of the new product. It could tell doctors the original product is not safe or has worse side effects.

Why would a company disparage and disadvantage its own product? The answer lies in the dynamics of pharmaceutical competition. A pharmacist can fill a prescription for a branded product with a bioequivalent generic. That is why a branded product loses share so quickly to its generic alternative. But the generic of the original product is not bioequivalent to the new version. Therefore, there is no substitution, and the branded company maintains its sales. According to one study, product hopping on just five products increased prescription drug costs by $4.7 billion a year.24

In an industry that prides itself on taking risks to develop life-saving drugs, product hopping is the opposite. The modifications are minor and involve little risk of value, but they provide little value to the patients. One need look no further than Asacol, a product used to treat ulcerative colitis, a chronic disease of the colon. As part of a product hop, Allergan, the manufacturer, put an Asacol tablet inside of a capsule and obtained approval for a new product, Delzicol. That is not innovation; it is just anticompetitive gaming of the system.

- Pay-for-delay patent settlements

Even when antitrust enforcement has had success, it is incomplete. A pay-for-delay patent settlement occurs when a branded company pays the generic or biosimilar company to delay launching its competitive product. The settlement eliminates the potential for competition. Both the branded and generic company profit at the expense of consumers.

The antitrust battle over these settlements has raged for roughly two decades. In a series of decisions that began in 2003, various courts concluded that this practice was acceptable.25 In these courts’ view, the fact that the branded company’s patent might exclude the generic meant that the branded company could pay the generic not to compete for any period of time until the patent expired.

These rulings had a devastating impact on generic competition. The number of potential pay-for-delay deals with significant payments increased from zero in fiscal year 2004 to a high of 33 in fiscal year 2012.26 The deals increased prescription drug costs by $63 billion.27

In 2013, in the Androgel case (FTC v. Actavis), the Supreme Court rejected the lenient view that patent holders could simply pay potential infringers to stay off the market. According to the Supreme Court, an agreement in which the branded and generic companies eliminate potential competition and share the resulting monopoly profits likely violates the antitrust laws, absent some justification.28 The Supreme Court’s decision has limited pay-for-delay deals. In fiscal year 2017, the most recent year of reported data, the number of potential pay-for-delay deals with significant payments fell to three.29

That success has been incomplete, and it overlooks the cost of enforcement. The Supreme Court approach requires a case-by-case analysis of a practice that virtually always is anticompetitive. That allows companies to find new ways to hide compensation or offer a plethora of alternative justifications for their conduct. Based on the past mistakes and some open hostility to the Supreme Court’s decision, courts could accept one of these defenses and create a costly loophole.

Further, the approach is resource intensive. Indeed, the FTC resolved the Androgel case itself almost 6 years after the Supreme Court decision allowing the case to go forward and more than a decade after the case was filed. The FTC continues to litigate multiple cases against the same parties over the same product.30

Anticompetitive conduct in prescription drug markets has been occurring for decades and has flourished despite the Federal Trade Commission having devoted substantial resources to trying to stop the conduct. It regularly litigates to judgment to stop egregious anticompetitive conduct with only limited success. The obstacles to successful enforcement are likely to increase because the Supreme Court has taken away the FTC’s ability to seek monetary remedies.

We are in this situation because “antitrust enforcement faces a serious deterrence problem, if not a crisis.”31 Judicial decisions have contributed to this problem. They “have thrown up inappropriate hurdles that limit the practical scope of the antitrust laws’ application to anticompetitive exclusionary conduct, including monopolization, and to anticompetitive mergers.”32 These developments make it less, not more, likely that antitrust law will condemn harmful conduct.

- Hostility to direct evidence of market power

In most antitrust cases, the plaintiff must prove that the defendant had market or monopoly power. A plaintiff can infer it by proving the relevant market and establishing that the defendant has a high market share. The alternative is to prove the actual anticompetitive effect of the conduct—such as higher prices, lower quality, and lower output.33 As the Supreme Court explains, “proof of actual detrimental effects, such as a reduction of output can obviate the need for an inquiry into market power, which is but a surrogate for detrimental effects.”34

Courts, however, increasingly shy away from direct effects evidence, making plaintiffs go through the often pedantic process of defining markets, particularly in pharmaceutical cases. Invariably, the impact of delaying or limiting competition is obvious. Delaying a generic or biosimilar competitor prevents prices from falling. That should end the market power inquiry. Courts, however, reject the obvious direct evidence for the less reliable market definition evidence.

In Mylan Pharms. Inc. v. Warner Chilcott, the court ignored the substantial impact generic competition would have on pricing. Instead, it relied on its own assessment of the qualitative similarities between the product at issue and other branded products. It defined the relevant market to include many products and found that the defendant’s market share was too small to establish market power.35 Even hen the court reaches the right result using the wrong methodology, it unnecessarily complicates the case and increases the cost of litigation.36

- Leniency toward dominant firms

In various ways, courts over the past four decades have limited the role of antitrust law in regulating conduct by dominant firms. A series of policy judgments have driven this development. Courts too often believe that monopolies spur innovation and discount the value of potential competition. Judicial doctrine reflects these policy choices. Courts are highly skeptical of refusals to deal and predatory pricing, even though modern economics establishes that such conduct can be successful in limiting competition and profitable.37 Exacerbating this tendency, courts often focus on the wrong facts.

These developments help explain why antitrust enforcement has struggled to stop anticompetitive conduct in prescription drug cases. In loyalty rebate cases, courts focus on issues such as whether the rebates increased and whether the practice eliminated competition completely, not whether the rebates allow the defendant to maintain its monopoly power by limiting competition. In product hopping cases, too often courts accept any proffered justification to dismiss the case, ignoring the obvious anticompetitive incentive and impact.38 In the pay-for-delay context, the fact that the eliminated competition was potential or uncertain led many courts to discount the harm.

One doctrine, refusals to deal, or when a firm refuses to deal with its competitor, deserves special mention. According to some courts, a refusal to deal can violate the antitrust laws only if the defendant has terminated an existing relationship. Under that standard, it is at least questionable whether the government would have been successful in breaking-up AT&T’s phone monopoly in the 1980s.39 This development should shock anyone who supports free markets and competition.

It also helps explain the rise of an anticompetitive strategy in prescription drugs. Some branded companies would prevent their potential generic competitors from obtaining samples of the branded product. Without those branded samples, the generic company could not conduct the tests necessary for approval. Members of the Senate Judiciary Committee identified the problem and introduced legislation, the CREATES Act, to solve the problem, which it did.40 If the courts had not whittled away the restrictions on monopolists’ refusing to deal with competitors, however, the practice may have never arisen.

- Weaker deterrence

Federal government antitrust enforcers have limited options to address the harm caused by anticompetitive activity, which is particularly problematic in prescription drug markets. The rewards are large. Delaying competition by a single year can generate hundreds of millions (and potentially billions) of dollars in additional revenue. If the government’s only remedy is an order forbidding the defendant from repeating the conduct, violating the law has little downside.

A recent Supreme Court decision exacerbated this dynamic. The Court determined that the Federal Trade Commission lacks the authority to seek monetary remedies for violations of the law. The FTC can not seek to compensate victims or deprive companies of the profits they earned by violating the law.41 This development will simply encourage pharmaceutical companies to adopt profitable, anticompetitive tactics that will further increase prescription drug costs.

The courts have made antitrust enforcement too difficult, although not impossible, and prescription drug markets are a prime example. The question for this committee and Congress is whether to accept the approach the courts have taken. Congress can correct these errors, restore the vitality of the antitrust laws, and deter anticompetitive conduct, which would inject competition into prescription drug markets. Two types of reforms exist: general antitrust proposals and laws tailored specifically to prescription drug markets.

- General antitrust reforms

There are broad principles Congress should enshrine to improve antitrust enforcement. First, direct evidence of anticompetitive effect should be sufficient for an antitrust case. Second, Congress can correct courts’ willingness to defer to dominant firms’ conduct by changing legal standards to stress that the risk of eliminating potential competition can violate the antitrust law. Congress should establish legal rules that, in appropriate cases and based on sound economics, require defendants to prove their conduct does not harm competition, and new legislation should nullify existing precedents that inappropriately limit antitrust law, such as precedents on refusal to deal and predation. Finally, Congress should restore the FTC’s authority to seek monetary remedies and give the government the ability to obtain civil fines for antitrust violations.42

Existing legislative proposals would address these issues. The Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act takes precisely this approach and would dramatically improve competition in prescription drug markets in particular, and throughout the economy generally.43 Although more limited, the Tougher Enforcement Against Monopolists Act would increase penalties, limit courts’ ability to rely on speculative justifications, and would require courts to find a violation where there is direct evidence of intent to harm competition.44

- Pharmaceutical-specific reforms

As the CREATES Act establishes, targeted solutions can be effective. A number legislative proposals are pending. Although the current Supreme Court rule on pay-for-delay settlements protects competition better than the lower courts had, it still has required the FTC to spend substantial resources to prevent clearly anticompetitive conduct. Congress should pass legislation that creates a strong presumption against pay-for-delay deals such as the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act. Not only would such legislation stop the practice, but it would also free up resources so that the FTC could investigate and challenge other anticompetitive activity in the pharmaceutical industry. Other specific legislation could address patent thickets, where a company accumulates substantial patents for the purposes of blocking entry, citizen petition abuse, and product hoping.

Conclusion

Anticompetitive conduct in pharmaceutical markets is a serious problem that increases costs and undermines healthcare, particularly for the most vulnerable in society. The competition problems in these markets flow, in substantial part, from four decades of judicial decisions that have enfeebled the antitrust laws. Prescription drug markets were one of the first areas to feel the effects of this development, but more industries are exhibiting similar problems. Congress needs to stem the tide of anticompetitive conduct by restoring the vitality of the antitrust laws.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify about this important question, and I am happy to answer any questions.

End Notes

1. See, generally, Nancy L. Rose, “Opening Statement of Professor Nancy L. Rose,” Testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Antitrust, Consumer Protection, and Consumer Rights, “Competition Policy for the Twenty First Century: The Case for Antitrust Reform,” March 11, 2021, available at https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/meetings/competition-policy-for-the-twenty-first-century-the-case-for-antitrust-reform; J. B. Baker and others, “Joint Response to the House Judiciary Committee on the State of Antitrust Law and Implications for Protecting Competition in Digital Markets,” April 30, 2020, available at https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiPhpf1itzxAhXUElkFHZdRAZcQFjABegQIBBAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fequitablegrowth.org%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2020%2F04%2FJoint-Response-to-the-House-Judiciary-Committee-on-the-State-of-Antitrust-Law-and-Implications-for-Protecting-Competition-in-Digital-Markets.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0tTA1Os9olu1tf91QjHBMH; Jonathan B. Baker, The Antitrust Paradigm: Restoring a Competitive Economy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019); Fiona Scott Morton, “Reforming U.S. antitrust enforcement and competition policy” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020). On labor market power, see Suresh Naidu, Eric Posner, and E. Glen Weyl, “Antitrust Remedies for Labor Market Power,” Harvard Law Review 132 (2) (2018).

2. Baker and others, “Joint Response to the House Judiciary Committee on the State of Antitrust Law and Implications for Protecting Competition in Digital Markets.”

3. Bill Baer and others, “Restoring competition in the United States: A vision for antitrust enforcement for the next administration and Congress” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2020), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/restoring-competition-in-the-united-states/?longform=true#promoting_competition_as_a_federal_government_priority.

4. Michael Kades, “The CREATES Act Shows legislation can stop anticompetitive pharmaceutical industry practices” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-creates-act-shows-legislation-can-stop-anticompetitive-pharmaceutical-industry-practices/.

5. For an example, see the discussion on product hopping, infra.

6. See Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditure by type of service and source of funds. CY 1960-2019” (n.d.), available at https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html.

7. Ashley Kirzinger and others, “KFF Health Tracking Poll – February 2019: Prescription Drugs” (San Francisco: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2019), available at https://www.kff.org/health-costs/poll-finding/kff-health-tracking-poll-february-2019-prescription-drugs/.

8. Patients for Affordable Drugs and its founder, David Mitchell, have put a human face on this issue by collecting and publishing the stories of individuals bearing the burden of high-cost prescription drugs See “Featured Stories, available at https://p4ad-main.friends.landslide.digital/our-stories/ (last accessed July 12, 2021).

9. Tomi Fadeyi-Jones and others, “High Prescription Drug Prices Perpetuate Systemic Racism. We Can Change It” (Washington: Patients for Affordable Drugs Now, 2020), available at https://patientsforaffordabledrugsnow.org/2020/12/14/drug-pricing-systemic-racism/.

10. AARP, “2019 Prescription Drug Survey – Hispanic/Latino Likely Voters” (2019), available at https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/health/2019/hispanic-latino-voters-prescription-drug-survey-fact-sheet.doi.10.26419-2Fres.00295.004.pdf.

11. Federal Trade Commission, “Emerging Health Care Issues: Follow-on Biologic Competition” (2009), available at www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/emerging-health-care-issues-follow-biologic-drug-competition-federal-trade-commission-report/p083901biologicsreport.pdf.

12. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “Some Observations Related to the Generic Drug Market” (2015), available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/139331/ib_GenericMarket.pdf.

13. Ibid.

14. IQVIA Institute, “Biosimilars in the United States” (2020), available at https://www.iqvia.com/insights/the-iqvia-institute/reports/biosimilars-in-the-united-states-2020-2024.

15. BIO, “What is Biotechnology” (n.d.), available at https://www.bio.org/what-biotechnology.

16. U.S. Food and Drug Administration, “What is a Biosimilar?” (n.d.), available at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/UCM585738.pdf.

17. Federal Trade Commission, “Emerging Health Care Issues: Follow-on Biologic Drug Competition.”

18. Kevin Dunleavy, “Special Reports: Humira” (New York: Fierce Pharma, 2021), available at https://www.fiercepharma.com/special-report/top-20-drugs-by-2020-sales-humira.

19. Merck and Co. Inc., “Financial Highlights Package Fourth Quarter 2020” (2021), p.9, available at https://mms.businesswire.com/media/20210204005437/en/857100/1/Final_~_Financial_Highlights_Package_01272021.pdf?download=1.

20. See Fiona Scott Morton and Zachary Abrahamson, “A Unifying Analytical Framework for Loyalty Rebates,” Antitrust Law Journal 81 (3) (2017): 777–836; Gianluca Faella, “The Antitrust Assessment of Loyalty Discounts and Rebates,” Journal of Competition Law and Economics 4 (2) (2008): 375–410, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=1146721.

21. U.S. Senate Finance Committee, “Insulin: Examining the factors driving the rising cost of a century old drug” (n.d.), p.66, available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Grassley-Wyden%20Insulin%20Report%20(FINAL%201).pdf. WAC is the wholesale acquisition cost.

22. Ronny Gal and Sanford Bernstein, “Biosimilars (June update): Market growth moderating as pricing offsets unit growth and innovators compete” (U.S. Biopharmaceuticals, 2021), ex. 3.

23. See, generally, Brief for the American Antitrust Institute, Sanofi-Aventis v. Mylan, No. 21-3005, 10th Cir., June 4, 2021, available at https://www.antitrustinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/TSAC-AAI-No.-21-3005.pdf.

24. Alex Brill, “The Cost of Brand Drug Product Hopping” (Washington: Matrix Global Advisors, 2020), available at https://www.affordableprescriptiondrugs.org/app/uploads/2020/09/CostofProductHoppingSept2020-1.pdf.

25. Federal Trade Commission v. Watson Pharms., Inc., 877 F.3d 1298 (11th Cir. 2012); Ark. Carpenters Health and Welfare Fund v. Bayer AG, 544 F.3d 1323 (Fed. Cir. 2008) In re Tamoxifen, 466 F.3d 187 (2nd Cir. 2005); Valley Drug Co. v. Geneva Pharms., 344 F. 3d 1294 (11th Cir. 2003).

26.

Federal Trade Commission, “Agreements Filed with the Federal Trade Commission under the Medicare

Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003” (2020), available at https://www.ftc.gov/reports/agreements-filed-federal-trade-commission-under-medicare-prescription-drug-improvement-10.

27. Michael Kades, “Competitive Edge: Underestimating the cost of underenforcing U.S. antitrust laws” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2019), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/competitive-edge-underestimating-the-cost-of-underenforcing-u-s-antitrust-laws/.

28. Federal Trade Commissionv. Actavis,570 US 136, 158 (2013).

29. Federal Trade Commission, “Emerging Health Care Issues: Follow-on Biologic Competition.”

30. Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Again Charges Endo and Impax with Illegally Preventing Competition in U.S. Market for Oxymorphone ER,” Press release, January 25, 2021, available at https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/01/ftc-again-charges-endo-impax-illegally-preventing-competition-us.

31. Baer and others, “Restoring competition in the United States: A vision for antitrust enforcement for the next administration and Congress.”

32. Ibid.

33. Federal Trade Commission v. Indiana Federation of Dentists, 476 U.S. 447 (S.Ct. 1986).

34. Ibid, pp. 460–61.

35. Mylan Pharms., Inc. v. Warner Chilcott, 838 F.3d 421 (3rd Cir. 2016).

36. Federal Trade Commission v. Abbvie, Inc., 976 F.3d 327 (2020).

37. For a discussion of these issues, see Baker and others, “Joint Response to the House Judiciary Committee on the State of Antitrust Law and Implications for Protecting Competition in Digital Markets.”

38. Mylan Pharms., Inc. v. Warner Chilcott, 838 F.3d 421 (3rd Cir. 2016).

39. Howard Shelanski, “The Case for Rebalancing Antitrust and Regulation,” Michigan Law Review 109 (5) (2011).

40. Kades, “The CREATES Act shows legislation can stop anticompetitive pharmaceutical industry practices.”

41. AMG Capital Management v. Federal Trade Commission, 144 S. Ct. 1341 (2021).

42. In this statement, I am focusing on reforms that would improve competition in the prescriptions drug markets. There are other reforms discussed in Baker and inBaer that would address problems in other areas such as monopsony. For a more detailed discussion, see Baker and others, “Joint Response to the House Judiciary Committee on the State of Antitrust Law and Implications for Protecting Competition in Digital Markets.” See also Baer and others, “Restoring competition in the United States: A vision for antitrust enforcement for the next administration and Congress.”

43. Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act of 2021, S. 225, 117th Cong. 1st sess. (2021), available at https://www.klobuchar.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/e/1/e171ac94-edaf-42bc-95ba-85c985a89200/375AF2AEA4F2AF97FB96DBC6A2A839F9.sil21191.pdf.

44. Tougher Enforcement Against Monopolists Act, S. 2039, 117th Cong. 1st sess. (2021), available at https://www.lee.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/23028e91-a982-43d0-9324-f6849c7522fc/hen21863.pdf.