Major federal ‘Big Tech’ antitrust case against Google will test the strength of current U.S. antitrust laws in new digital markets

A high-profile antitrust enforcement action taken in January by the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice against Alphabet Inc.’s Google unit—one of the largest technology companies in the world—could well determine whether existing U.S. antitrust laws remain relevant in the world of Big Tech.

Most immediately, the action will test the proposition that existing antitrust doctrines are applicable in these new, high-tech markets. More broadly, an eventual court decision in the case could help inform the U.S. Congress whether it will need to update U.S. antitrust laws to deal with Big Tech digital market concentration after the previous Congress failed to do so.

The new federal case alleges that Google consolidated its market power by acquiring its potential competitors, then used its market power to manipulate auction markets—where advertising space is sold to the highest bidder in real time—playing one side against the other. The Antitrust Division argues this is not a coincidence, but rather was a deliberate strategy by Google to thwart competition for its own gain.

To remedy these harms, the agency is asking the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia to break the connection between Google and its advertising business. Breaking up a company is a serious remedy but not an unprecedented one. Where a breakup is the goal, though, enforcers must have it in their sights from the outset and build their case around it.

But will the federal government be able to effectively address competition concerns in these modern markets with tools designed in another era? U.S. antitrust law, which dates back to the late 19th century and has been refined by the U.S. Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court since then, is well-suited to handle routine antitrust enforcement in traditional industries. But the business practices and strategies playing out across the U.S. digital technology sectors and beyond are not always easily connected to the historic applications of U.S. antitrust law.

That’s why this new enforcement action by the federal government is so important. The Google case will test whether the analytical tools that Justice Department antitrust lawyers present can make sense of these (and other) digital technology markets and the competitive dynamics within them—and thus, whether courts and antitrust enforcers can apply longstanding, fundamental U.S. antitrust laws to allegedly monopolistic practices in the context of new technologies. The antitrust laws are broad and designed to evolve with markets and technologies, but applying them to these new technology markets still raises hard questions.

Applying evidence in antitrust cases in digital markets

A new book published in late 2022 by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Judging Big Tech: Insights on applying U.S. antitrust laws to digital markets, offers the judge who will handle this case and the attorneys who will prosecute it some useful ways to think about how to present and assess the evidence.

In the first chapter of the book (beginning on page 10), legal scholar Harry First, the Charles L. Denison Professor of Law at New York University School of law, uses the lens of the 2001 antitrust case, United States v. Microsoft Corp.,to examine tech remedies. First makes a compelling case that only by developing the right kind of evidence and thinking creatively about the tools to be deployed can antitrust enforcers realistically hope to obtain structural relief of this nature. Because the case for a breakup must be built throughout the case, First emphasizes that enforcers must start their case with that ultimate goal in mind.

To get to a remedy, though, the question of liability must first be resolved. The Justice Department’s complaint against Google draws on another theme addressed by the book: the acquisitions of nascent competitors. In the second chapter of the book (beginning on page 38), Doug Melamed, a professor of the practice of law at Stanford Law School, provides a much-needed framework for distinguishing problematic acquisitions of nascent or potential competitors from the overall run of productive acquisitions of small companies that provides the engine for dynamic U.S. start-up industries.

Melamed also explains why antitrust enforcers must steadfastly pursue problematic acquisitions, even though they are the exception to most nascent acquisitions. He presents detailed technical analysis of the ways in which enforcers can distinguish between these run-of-the-mill acquisitions and those with the potential to extinguish a true competitive threat, where the costs to innovation and to consumers are enormous.

The importance of intent evidence in the case of Big Tech antitrust cases

In the fourth chapter of the book (beginning on page 97), Marina Lao, the Edward S. Hendrickson Professor of Law at Seton Hall University’s School of Law, adds a forceful argument for the central role of evidence of intent. Even where it is not an element of a violation, traditional evidence of intent can be a powerful window into how those who know the industry and the players best—the players themselves—view acquisitions and other conduct.

The Department of Justice’s complaint against Google reflects this understanding of the evidence in the case, including citations to internal Google emails to show that those within Google were aware of the competitive implications of Google’s strategy and conduct. This kind of evidence is sometimes dismissed as “unscientific” in favor of quantititative evidence—the result of the influence of the so-called Chicago School of conservative legal antitrust scholars, notes Lao.

Beginning in the late 1970s and early 1980s, “under the influence of the Chicago School, economic efficiency became antitrust law’s main objective and neoclassical economic (or price) theory the preferred analytical tool,” she writes. “During this time, antitrust law also turned strongly in favor of quantitative evidence and economic analytical tools.” Yet intent evidence is the type of documentary evidence that is particularly valuable in the context of rapidly evolving and highly complex tech markets, where the players are arguably better able to perceive the impact of their conduct than economic modeling.

Quantitative evidence often fails to paint a clear picture of competitive effects when innovation and other nonprice harms to competition defy quantification or easy measurement. This creates major problems of proof for antitrust enforcement in digital technology markets, where there is a growing consensus that a narrow focus on price effects fails to capture the scope of competitive harm. Lao argues that reviving recognition of intent evidence in monopolization cases in markets marked by rapidly changing technologies—such as those involving digital platforms—can help strengthen antitrust enforcement by enabling judges to use traditional documentary evidence and the defendants’ own expertise about their products and markets to contextualize quantitative economic evidence and evaluate competitive dynamics in complex and rapidly changing markets.

The salience of anticompetitive conduct across multiple markets

A final issue of particular salience, in light of the nature of the federal antitrust allegations against Google, is how courts should address conduct that impacts multiple interrelated markets. The core allegation in the Department of Justice’s lawsuit is that Google controls all of the platforms that mediate advertising transactions between website publishers and advertisers, and exercises its power across these platforms to harm both publishers and advertisers—and competition generally.

But this raises the tough question of whether and how the impacts of Google’s conduct across multiple markets should be weighed against each other. As Erika Douglas, an associate professor of law at Temple University’s Beasley School of Law, argues in chapter 3 of the book (beginning on page 67), there is currently no clear framework for reconciling these varied effects across markets. Douglas interrogates and rejects the idea that clear precedent precludes balancing harms and benefits across different markets but argues that from first principles and sound reasoning, courts should nonetheless exercise extreme caution in this area.

Indeed, in the vast majority of antitrust cases, she writes, conduct should be evaluated based on its impact (good and bad) on a single market. Only in very particular circumstances should courts consider cross-market effects, and when they do so, they should do it forthrightly, not by stretching market definition to its breaking point, as in the highly criticized Supreme Court decision in Ohio v. American Express Co. Instead of distorting market definition principles, the American Express case should have directly addressed cross-market justifications, Douglas argues. The Department of Justice’s current case against Google includes the same cross-market issues.

Conclusion

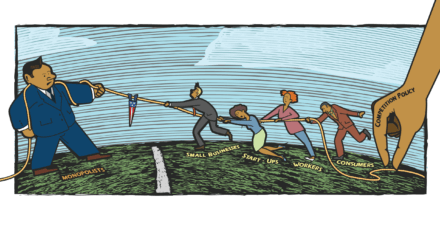

The importance of digital information technology and communications giants to the U.S. economy and society today is undeniable, which is why the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission—the two federal enforcers of antitrust law—are carefully examining the business strategies of these Big Tech companies. This increased focus is appropriate, given that Google, alongside Meta Inc. (the parent company of Facebook), Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc., and Microsoft Corp., are the main arteries for the U.S. public’s social and commercial engagement online.

Antitrust enforcement agencies are particularly interested in these companies because of the ways in which the dominant technology firms are expanding their businesses and how those decisions affect U.S. consumers, businesses, and workers. How the antitrust case against Google plays out in court will have outsized significance to U.S. economic competitiveness—and consequently to future economic productivity and growth and broader U.S. societal well-being. It will also prove to be a critical bellwether, indicating just how relevant antitrust remains in modern markets. Judging Big Tech provides new and valuable legal tools and insights from antitrust experts that judges and others can use to guide the way through this first wave of digital platform antitrust cases and plot a course for antitrust’s future.