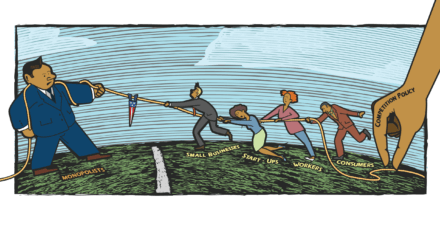

New research suggests connections between market concentration and the exercise of political power in the United States

Consolidation of markets at the hands of U.S. companies that are actively engaged in mergers and acquisitions raises an important question about the political ramifications of market concentration. Do mergers and acquisitions impact the lobbying clout of these acquisitive firms? A new working paper delves into this connection and finds some intriguing, if also preliminary, affirmative evidence.

“Political Power and Market Power,” by Bo Cowgill and Andrea Prat at Columbia Business School and Tommaso Valletti at the Imperial College Business School, documents a positive association between mergers and lobbying activities, and finds some evidence for a positive association of mergers with political campaign contributions. These findings and the economic model the co-authors employ in their research are not robust enough, as is, for U.S. antitrust enforcers to measure these connections between political power and market concentration quantitatively, though the findings advance conceptional frameworks for better understanding this nexus in the qualitative context of the political economy of the United States.

But first, let’s briefly examine the findings and methodology of the new working paper. Cowgill, Prat, and Valletti develop a model that extends a standard theoretical model of industrial organization and competition to include government regulatory variables. They then use two different empirical approaches to study the relationship between merger data and lobbying spending data. Specifically, they match data from 1999 to 2017 of companies registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission with data on federal lobbying from the nonprofit data science firm LobbyView, campaign contributions tracked by the nonprofit government transparency organization OpenSecrets, and mergers and acquisitions transactions from the SDC Platinum Financial Securities Data, provided by Refinitiv (formerly Thomson Reuters).

The co-authors find that increases in lobbying spending associated with mergers is modest, at around 22 percent, or around $74,000 to $106,000 per 6-month period of analysis. The increase in campaign contributions is only $4,000 to $10,000 per 6-month period and is not statistically significant in all specifications. But the authors do find that larger mergers and mergers between companies in the same industry are more strongly associated with increased lobbying spending, which is consistent with the idea that the increase in this spending is associated with increased market power.

The topline result of their findings is that mergers and lobbying spending are positively correlated. The stronger correlation observed when mergers occur within a single industry suggests, at a high level, that increased market concentration correlates with increased spending on political influence.

Yet there are some caveats worth noting. First of all, a lot of spending on lobbying activity goes unreported to the IRS. Secondly, this spending often occurs through trade associations. Both of these lobbying dynamics means the data used in “Market Power and Political Power” is far from complete.

A third caveat is that one might expect merged firms with more market power to become better at exerting political influence outside of traditional lobbying. This is particularly relevant when attempting to measure the impact of mergers and lobbying in legislative outcomes, where the spend on lobbying may not reflect effective political clout.

Nonetheless, Cowgill, Prat, and Valletti advance ways in which economists and political scientists alike can examine the connection between market power and political power in the United States. How does rising market concentration directly affect consumers through market power—potentially raising prices and reducing output—but also indirectly, through the increased political influence of merged firms and these firms’ abilities to influence regulations governing their operations?

Indeed, this new working paper is a strong theoretical first step in understanding the nexus between political power and rising market concentration due to mergers and acquisitions. Of particular interest is a new unit of analysis the co-authors develop called a composite firm, or a cluster of multiple firms that eventually merge together by the end of the data analysis period. This is a potentially useful tool for future study of the impacts of mergers over time.

Importantly, though, economists and political scientists are not limited to looking at political influence in antitrust analysis through quantitative economic tools alone. Quantitative modeling is a critical part of merger analysis, but federal antitrust enforcers at the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice do not need to rely solely on quantitative economics in assessing merger impacts. Qualitative evidence is equally important, as several authors note in Equitable Growth’s most recent book, Judging Big Tech: Insights on applying antitrust laws in digital markets.