Tax evasion at the top of the U.S. income distribution and how to fight it

How much taxes do high-income Americans evade? And what kinds of evasion tactics do they use? These questions are important for tax enforcement policies and the measurement of income inequality in the United States. Answering them can improve tax enforcement policy and the fairness of federal fiscal policies more broadly, a key priority as policymakers attempt to build a more equitable economy in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

In a new study conducted in collaboration with researchers at the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, we show that American taxpayers with incomes in the top 1 percent are much more sophisticated than the other 99 percent at tax evasion. As a result, conventional estimates significantly underestimate the income and taxes evaded by the rich.1

Our findings point to several key steps that policymakers could take to combat widespread tax evasion by the very top income earners in the United States. First and foremost is the need for greater fiscal support for the IRS. Second, the IRS and Congress can target the ways in which the rich hide their incomes and obscure their actual tax obligations via so-called pass-through businesses and hidden offshore accounts.

Random audits and the tax gap

The IRS estimates that about 16 percent of all federal taxes go unpaid. A 16 percent tax gap means that $1 out of every $6 of taxes that should legally be paid is not paid. The IRS estimates that about 60 percent of the tax gap comes from underreporting of income on individuals’ tax returns. Conventionally, researchers at the agency and academics estimate this part of the tax gap with data from random audits. Most IRS audits are, of course, not random. The IRS generally prioritizes tax returns that it expects, based on a variety of factors, to be noncompliant. But to estimate the size of tax evasion and study its nature, the IRS also audits a number of returns randomly.

Our research shows that random audits may paint an accurate picture of the tax gap for 99 percent of taxpayers, but not for the top 1 percent. According to random audit data, all groups of the population underreport about 4 percent to 5 percent of their income on average. The only exception is the very top of the income distribution. Within the top 0.1 percent—taxpayers with income of more than $1.7 million—detected tax evasion falls to extremely low levels.

Interpreted naively, these data suggest that high-income people evade little when paying taxes. But substantial evidence from other sources of data, and many headlines that readers might recall, suggest that high-income tax evasion is far from minimal. Our new research provides concrete evidence that at least two types of tax evasion are quantitatively significant at the top of the U.S. income distribution and typically not detected through random audits.

What random audits miss

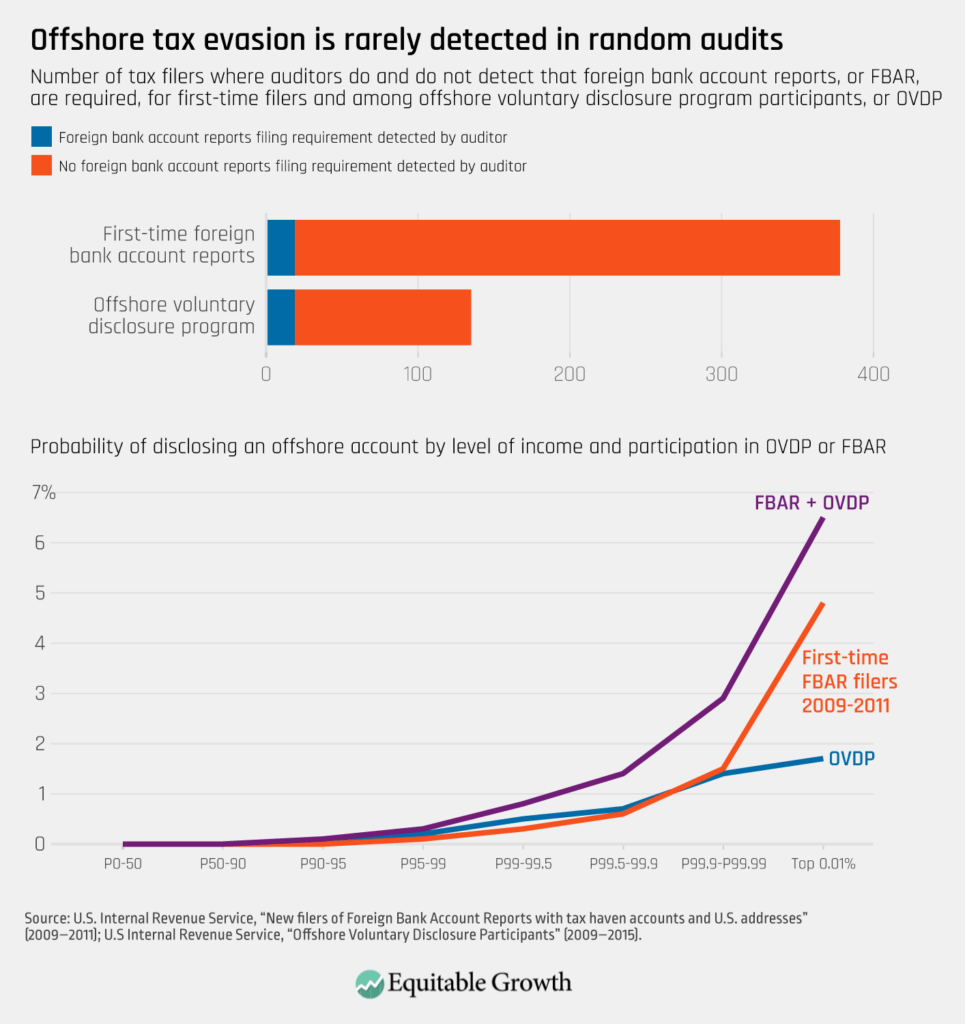

One type of tax evasion missed by random audits involves concealed offshore wealth.

Starting in 2008 and culminating in the Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act of 2010, the IRS conducted an ambitious initiative to crack down on offshore tax evasion. As documented in a prior study, this initiative led tens of thousands of U.S. taxpayers to disclose previously hidden offshore assets, such as bank accounts in Switzerland, either in the context of the IRS “Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program” or by wealthy U.S. individuals filing Foreign Bank Account Reports for the first time around the time of the crackdown in 2009–2011.

Among these taxpayers, hundreds had been randomly audited in the years immediately preceding their disclosure of unreported offshore assets. These individuals’ offshore tax evasion had not been detected in random audits, however, because even excellent auditors have difficulty detecting hidden offshore wealth. Moreover,offshore tax evasion is extremely concentrated at the top of the U.S. income distribution. Less than 1 in 1,000 individuals in the bottom 99 percent of the income distribution appear on our lists of taxpayers disclosing an offshore account following the crackdown. In contrast,about 1 in 15 people in the top 0.01 percent appear on these lists—lists that, according to the prior study, probably only capture 10 percent to 15 percent of all offshore evasion. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Another source of tax evasion missed by random audits involves so-called pass-through business income.

Pass-through businesses (partnerships and S-corporations under the U.S. tax code) do not remit their own income taxes but rather this income “passes through” to their owners for tax purposes. Pass-through business income is highly concentrated at the top of the income distribution. Partnerships in particular can be highly complex because the owners of partnerships can be other pass-through businesses. And when an auditor encounters pass-through income during an individual random audit, we observe that they only proceed to audit the pass-through businesses themselves in less than 5 percent of cases. Consequently, random audits uncover very little pass-through business tax evasion, even though the complexity of these businesses can facilitate substantial evasion.

Our research shows that correcting, conservatively, for these two forms of undetected sophisticated tax evasion significantly changes the picture of tax evasion at the top of the income distribution painted by random audit data. Accounting for sophisticated tax evasion approximately doubles the tax gap for the top 0.1 percent of the U.S. income distribution, compared to conventional estimates. Additionally, accounting for underreported income increases estimates of the share of all income received by the top 1 percent by about 1.5 percentage points, which highlights the value of our findings for the measurement of inequality with data from tax returns.

Why is sophisticated tax evasion so concentrated at the top? In our working paper, we propose a new theoretical explanation based on three ideas. First, the concealment of tax evasion from auditors is costly, requiring substantial financial sophistication. Second, high-income people can save huge amounts of tax with little risk by adopting sophisticated strategies, which makes it worth the cost. Third, audit rates are relatively high at the very top of the income distribution, so if the audits are not thorough enough to correct sophisticated evasion, then frequent audits themselves incentivize the concealment of tax evasion.

Policy implications

Our results are important for the effective enforcement of tax evasion among very high-income Americans. First, existing statistics on total tax evasion at the very top of the U.S. income distribution are substantially underestimated. Second, the sophistication of top-end tax evasion suggests that increasing audit rates of high-income individuals alone may limit our progress.

Effective tax enforcement at the very top of the U.S. income distribution requires a more comprehensive approach. Strategies that would improve enforcement of tax evasion include:

- Greater scrutiny of pass-through businesses

- More comprehensive audits, such as those conducted in the IRS Global High Wealth program

- More thorough litigation of tax disputes

- New regulations to explicitly prohibit legally dubious “avoidance” strategies

- Programs to encourage whistle-blowing

The IRS already invests in many of these enforcement strategies, but budget cuts have severely curtailed the agency’s ability to conduct them efficiently and effectively.

We conservatively estimate that increased enforcement to close the income tax gap for the top 1 percent could yield $175 billion in currently uncollected income tax revenue per year. To put that in perspective, this would be enough revenue to make permanent the $3,000 to $3,600 annual child allowance in the American Rescue Plan and then make it about 50 percent more generous. Even modest success at enforcing taxes on the richest Americans could dramatically improve the fairness and progressivity of our tax system.

—Daniel Reck is an economist at the London School of Economics. Max Risch is an economist at the Carnegie Mellon University Tepper School of Business. Gabriel Zucman is an economist at the University of California, Berkeley.

End Notes

1. The paper is a collaboration between ourselves and two IRS co-authors, John Guyton and Patrick Langetieg. The views in the working paper and this article are our views and not the official position of the IRS.