Competitive Edge: The future of vertical mergers and the thing called ‘EDM’

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Jonathan Sallet has authored this contribution.

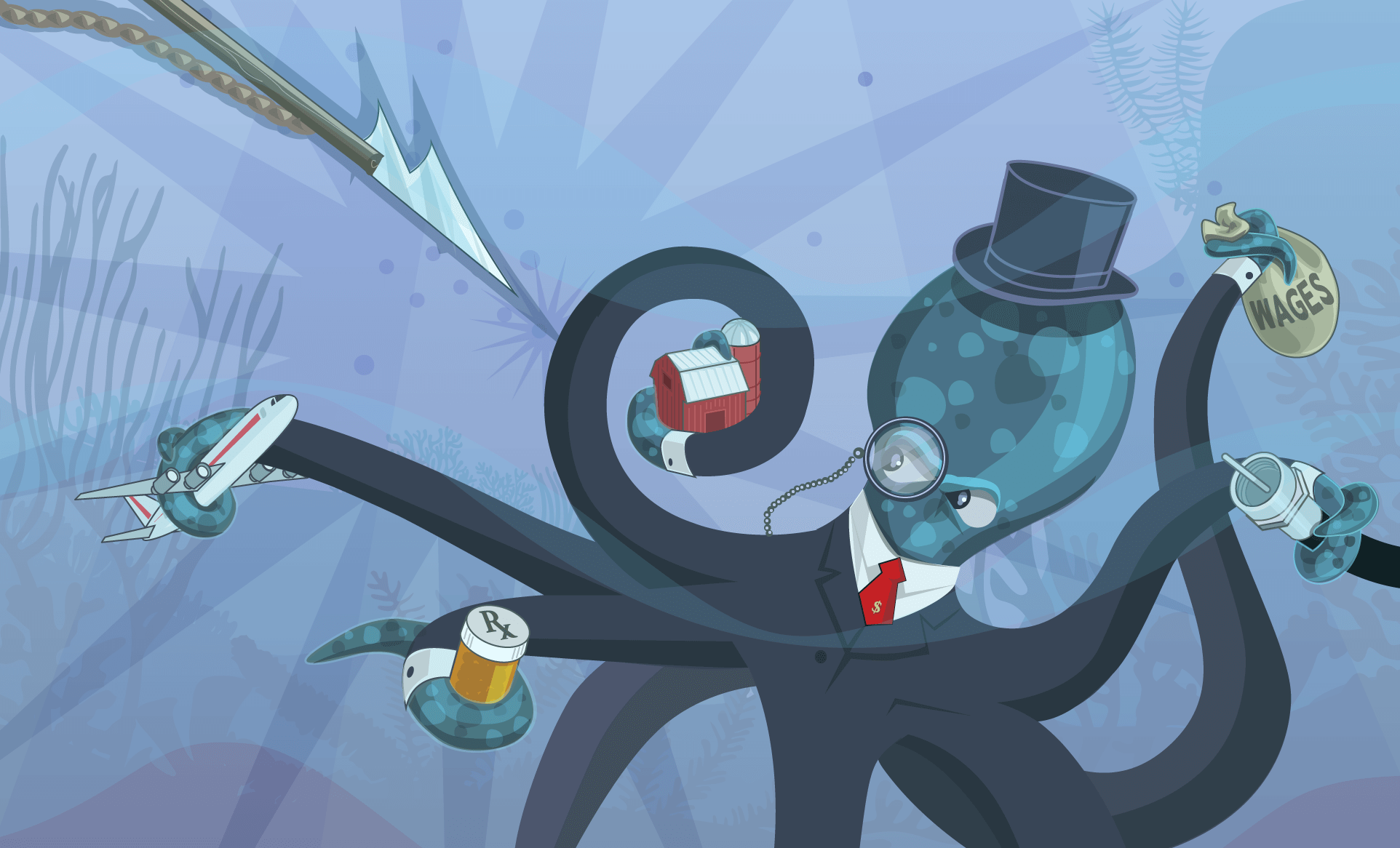

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

The previous time federal antitrust agencies issued formal merger guidelines dealing with vertical mergers was in 1984. They and the entire antitrust community have learned a lot in the past 36 years.

Economic analysis of vertical mergers has evolved and been refined, and the thinking at the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division and the Federal Trade Commission has similarly advanced. During that time, in a series of consent orders, antitrust enforcement carefully explained how vertical mergers can harm competition in industries ranging from agriculture to aerospace to energy to the internet and telecommunications. In 2019, the Federal Trade Commission, for example, confronted vertical merger issues in its decisions in two merger cases: office supply firm Staples Inc.’s acquisition of Essendant Inc. and UnitedHealth Group’s acquisition of DaVita Medical Group. The UnitedHealth Group/DaVita merger also made history when, for the first time, the Colorado attorney general entered into a separate consent decree in a vertical merger to protect competition in that state.

In January, the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division issued draft Vertical Merger Guidelines to capture their learnings and experience. Importantly, these guidelines paid no mind to the often-claimed and ill-supported notion that vertical mergers are inherently procompetitive. Instead, the two agencies explained carefully that Section 7 of the Clayton Act, which bars mergers “the effect of which may be substantially to lessen competition,” applies just as much to vertical as to other mergers.

Yet, an issue that is, even by antitrust standards, relatively arcane threatens to undo that progress and resurrect the notion that vertical mergers are presumptively procompetitive. The antitrust agencies need to reject that notion—in whatever form it appears.

The issue is called EDM. This is not an acronym for electronic dance music or even a garbled reference to a ‘90s rock band. EDM stands for “elimination of double marginalization,” which sounds harder than it is.

Consider a supplier of television programming and a cable system. The TV programmer makes a profit (which is to say, a margin) on its sales to the cable system, and the cable system makes a profit (another margin) by selling Pay TV packages to consumers. If the price to consumers of the Pay TV package were lowered, then the cable system might sell more and make more and so, too, might the TV programmer. So, that TV programmer might agree to lower its price to the cable system, allowing them to share the burden of lowering their profits but also sharing the extra revenue that comes from selling cooperatively to more consumers at a lower price.

But let’s say, for some reason, the TV programmer and the cable system can’t reach a deal. Then, if the cable system acquires the TV programmer, the merged firm could implement the same strategy by eliminating the margin on the sale of television programming and selling the Pay TV package to consumers at a lower price. This, simply put, is elimination of double marginalization. If EDM actually occurs, then there’s no doubt it’s a competitive benefit that can be weighed against the risk of anticompetitive harm.

That’s what merger analysis does. It looks at the likelihood of competitive harm and then considers whether there are offsetting competitive benefits that negate the risk of harm. These kinds of competitive benefits typically include so-called efficiencies, such as the ability of the merged company to produce more with less.

But now there is doubt whether the agencies will treat EDM the same as other claimed benefits. That’s because the agencies organized the draft Vertical Merger Guidelines in a way that separates EDM from efficiencies. And some comments to the agencies argue that EDM should be assumed, meaning that some such margin reduction will occur. Assuming there will be a reduction in margins is effectively a presumption in favor of EDM.

A presumption that EDM exists would vastly complicate the ability of federal and state antitrust enforcers to challenge vertical mergers and would lead to underenforcement. That’s because a judge might start by presuming that competitive benefits exist and then would assess whether there’s a risk of competitive harm. The government, in other words, could start off behind.

For five separate reasons, that’s wrong, and the antitrust agencies need to clarify their final guidelines to make plain that claims of EDM are to be presented and assessed the same as any other claimed procompetitive benefit. These five reasons are:

- Vertical Merger Guidelines will be important to future litigation of vertical merger challenges.

- The Department of Justice has spoken plainly that merging parties must support and quantify EDM as a defense.

- The Department of Justice’s view is amply supported by antitrust statute and precedent.

- Merging parties have the information and incentive to develop facts about their own internal operations, including EDM.

- Economic models and analysis do not support a contrary conclusion.

Let’s consider each in turn.

Vertical Merger Guidelines will be important to future litigation of vertical merger challenges

As a technical matter, the Vertical Merger Guidelines will apply only to the agency investigations, but the federal courts are sure to look to them for guidance. That’s been the case in horizontal mergers, which have been litigated with some frequency, so the guidance supplied to courts will be even more important for vertical mergers, where litigated challenges have been exceedingly rare. And that means any implication of differential treatment of EDM could adversely impact the federal and state enforcers’ ability to successfully challenge vertical mergers. This also could have the effect of pushing federal and state enforcers toward a more permissive stance toward the vertical mergers that come in the door.

The Department of Justice has spoken plainly that merging parties must support and quantify EDM as a defense

The implication that EDM is a different kind of antitrust animal is demonstrably wrong. The Department of Justice has made plain that if merging parties “want credit for EDM, then they have to do the work, and have the evidence necessary to support it.” Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim explained last year very forthrightly that “[o]ur approach at the Antitrust Division is this: as the law requires for the advancement of any affirmative defense, the burden is on the parties in a vertical merger to put forward evidence to support and quantify EDM as a defense.” The Antitrust Division at the Justice Department took the same position in the AT&T Inc./Time Warner Inc. litigation when it discussed “efficiencies—such as the elimination of double marginalization.”

The Department of Justice’s view is amply supported by antitrust statute and precedent

The U.S. Congress designed Section 7 of the Clayton Act to stop anticompetitive conduct before it harms consumers. As the D.C. Circuit Court said in its AT&T/Time Warner opinion, “Congress acted out of concern with ‘probabilities, not certainties’ and charged the courts with ‘halting incipient monopolies.’” That’s why the government wins if it establishes a “reasonable probability” of harm to competition because it doesn’t have to eliminate every possibility to meet its burden. As Assistant Attorney General Delrahim said, “the Antitrust Division is not required to present, in its case-in-chief, evidence rebutting or anticipating the defendants’ affirmative claim that EDM will cause a price decrease.”

Merging parties have the information and incentive to develop facts about their own internal operations, including EDM

The burden of demonstrating EDM belongs on the merging parties because it’s the merging parties that have the information and incentive to develop facts about their own internal operations. The comments of 28 state attorneys general on the draft Vertical Merger Guidelines explain in detail that the merging firms have superior knowledge on topics such as what margins have existed, past actions (such as contracts) that have been considered or tried, the incentives and opportunities to reduce margins in the future, and, of course, how their plans will change as they plan the operations of the merged company. All of this goes to merger specificity, according to the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines issued jointly by the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission: “The Agencies credit only those efficiencies likely to be accomplished with the proposed merger and unlikely to be accomplished in the absence of either the proposed merger or another means having comparable anticompetitive effects.”

For any inquiry into the elimination of double marginalization, facts are critical. As the Department of Justice has said, “it is impossible to tell at first blush whether a vertical merger will eliminate double marginalization and, if it does, how large a savings that would create for consumers.” EDM might be small or nonexistent; indeed, Steven Salop at Georgetown Law School presented eight separate reasons to support that conclusion at the Department of Justice’s Workshop on Vertical Mergers held on March 11, 2020.

So, for example, as the draft Vertical Merger Guidelines expressly note, the downstream affiliate may not be able to efficiently use the upstream affiliate’s product. Or the new firm may instruct its upstream and downstream affiliates to operate independently. Or the upstream affiliate, which would give up its margin for the good of the new firm, may have limited capacity, which means that it could not produce more units even if its downstream affiliate cuts its retail price. The upshot: Without the ability to produce more units, there would be no incentive to lower retail prices.

And what if the price reduction reduces input sales that the upstream affiliate would have made to other downstream competitors? In that case, the merged firm might raise prices to coordinate higher prices, rather than lowering prices through the elimination of double margins.

Thus, “EDM must be shown to be merger specific to be credited,” which is “a factual question that must be assessed on a case-by-case basis.” For example, in the successful union of Comcast Corp. with NBC Universal, the Department of Justice procured a consent decree limiting the action of the merged firm after considering an EDM defense, but concluding that “[d]ocuments, data, and testimony obtained from Defendants and third parties demonstrate that much, if not all, of any potential double marginalization is reduced, if not completely eliminated, through the course of contract negotiations.”

These are all fact-specific questions that the merging parties are best positioned to answer. They have better access to facts and a healthy incentive to find them. By contrast, according to the Department of Justice, if antitrust enforcers “bore the burden on efficiencies, ‘the efficiencies defense might well swallow the whole of Section 7 of the Clayton Act because management would be able to present large efficiencies based on its own judgment and the Court would be hard pressed to find otherwise.’” Moreover, if the government had the burden of disproving EDM, companies might have the incentive to not cooperate.

Economic models and analysis do not support a contrary conclusion

I recognize the contention that the existence of EDM may be linked to the existence of incentive to harm competition (specifically by raising rivals’ costs). But in their Vertical Merger Guidelines comments, professors Jonathan Baker at American University’s School of Law, Salop at Georgetown Law, Nancy Rose at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Fiona Scott Morton at Yale University tell us that “the economics literature does not support the proposition that there is a reliable relationship between EDM and raising rivals’ costs.” Salop specifically has explained that not all models treat EDM and raising rivals’ costs as linked. And Scott Morton, with Marissa Beck at Charles Rivers Associates, submitted comments in which they carefully reviewed past studies and concluded that vertical mergers are not generally procompetitive and that “the effects of a vertical merger will depend on the specifics of the transaction and markets at issue.”

Conclusion

In sum, as professor Martin Gaynor at Carnegie Mellon University has told the agencies, “EDM is not, in general, a necessary consequence of vertical (non-horizontal) integration. All of this is why, as Carl Shapiro, the government’s testifying expert in the AT&T/TWE case, said in his comments, ‘EDM, like all other efficiencies, must be shown to be cognizable before it can be credited.’”

That’s correct. EDM should be treated like any other claim of competitive benefits arising from a merger, through the analysis traditionally applicable to efficiencies. And that is what, in accordance with the Department of Justice’s repeated views, the final Vertical Merger Guidelines should say.

—Jonathan Sallet is a senior fellow at the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society. He also assists the antitrust work of the Colorado attorney general’s office as a special assistant attorney general. The views expressed here are his own.