Weekend reading: Working to close racial gaps in economics, the workforce, and education edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

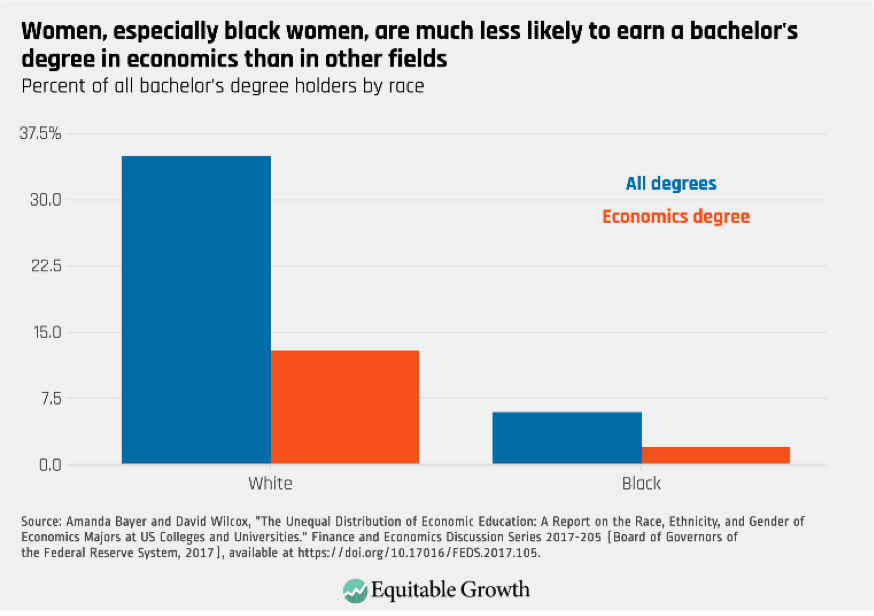

We need more black women economists in the United States, argues Claudia Sahm in her most recent column covering the Federal Reserve. Not only is there just one black woman economist working at the Federal Reserve Board, but black women also make up a miniscule percentage of undergraduate economics students and recent Ph.D.s. This lack of diversity in the profession and in the ranks of decision-makers means that economists don’t have as wide a perspective on certain issues that are necessary to accurately study them, and that race has played less of a role than it should in the Fed’s policy discussions. And while the Fed is working to change that fact through efforts to improve staff diversity, more needs to be done to increase the number of women, and black women in particular, who enter the field. Sahm concludes by discussing her recent experience with the Sadie Collective, a group working to do just that.

In the latest “Equitable Growth in Conversation,” Kate Bahn talks with sociologist Adia Harvey Wingfield about racial and gender inequality in the U.S. labor market, the consequences of that inequality, and policies that can work to improve it. Bahn and Wingfield’s conversation dives into Wingfield’s research, which looks at the intersections of race and gender in service industries in the United States, particularly in healthcare, and how the work of making these fields more accessible and equitable for people of color tends to fall on the shoulders of people of color already working in those areas. The effects of this added burden are profound—burnout, alienation, feeling exploited—in short, “it’s simply too much,” says Wingfield. But there are things that can be done to can help workers of color, she continues, including providing them with more resources and support and making certain structural changes in organizations and companies.

If the public education system in the United States improved the way it teaches African American history and the implications of slavery, Jim Crow, and racial discrimination, perhaps the black lived experience would be better understood by everyone, write Robynn Cox and Dania Francis. The authors of two chapters from our recently released book, Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, opine that because U.S. public education tends to gloss over our nation’s sordid past, the legacies it has left behind—which still profoundly affect African Americans to this day, despite all the gains made over the past 150 years—are often misunderstood, disbelieved, or ignored. This means that the various documented inequalities faced by African Americans, from health to wealth, become ever more challenging to address. Cox and Francis argue for several policy ideas that would elevate the largely untaught aspects of U.S. history and the African American experience in order to better equip ourselves and future generations to address these gaps and inequalities.

For more information about our new book, Vision 2020: Evidence for a stronger economy, and the launch event we hosted last week, check out David Mitchell’s post detailing the release and the chapters of the four speakers who sat on the event’s panel. The speakers were Cox, whose chapter looks at race and criminal justice policy; Susan Lambert, whose chapter addresses work schedule instability and unpredictability; Fiona Scott Morton, whose chapter dives into increased concentration in the U.S. economy and antitrust reform; and Equitable Growth president and CEO Heather Boushey, whose chapter argues for new metrics to measure inequality and economic growth in order to show how the economy is delivering for all Americans. The authors also each sat for short video interviews detailing their research and work, which you can find in Mitchell’s post.

Colorado and 26 other states filed comments with the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission this week regarding their proposed Vertical Merger Guidelines. Colorado’s Attorney General Phil Weiser penned a Competitive Edge post explaining the comments and the areas of competitive harm that warrant attention by the two agencies—namely, that vertical mergers can be as harmful to competition as horizontal mergers, and highlighting the use of anticompetitive merger remedies in vertical mergers.

Links from around the web

American workers today are struggling because U.S. labor laws are unable to help and protect them, writes Emily Bazelon for The New York Times. To show just how broken these laws are, especially for low-wage workers, she takes an in-depth look at a case involving the National Labor Relations Board and McDonald’s Corp. The case exemplifies how the Trump administration has repeatedly undermined the National Labor Relations Act, which is meant to protect the rights of workers to unite to improve their working conditions. In detailing the long history of the law—which was passed in 1935 by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt—Bazelon explains how it originally benefitted workers and increased union membership, and then how big business responded and has since overwhelmed the power of workers and unions in the United States.

In an age when almost everyone appears affected by inequality—when “almost everyone is reckoning with financial crises, climate disaster and economic insecurity”—it can be difficult to explain what, exactly, is different about racial inequality, writes Tressie McMillan Cottom for TIME. Racial oppression may be less overt, less visual these days than when slavery or segregation made it unavoidably obvious, but black people still have to work much harder than their white counterparts to stay afloat—and forget about getting ahead. McMillan Cottom goes through exactly what it means to “hustle,” how black communities are hustling on every rung of the income ladder, and how even that hasn’t allowed them to move up the ladder, despite the gains made since the civil rights movement: “For black Americans, achieving upward mobility, even in thriving cities that compete for tech jobs, private capital and national recognition, is as complicated as it was in 1963. … [In 2020] despite hustling like everyone else, they do not have much to show for it.”

New research shows that the United States has been measuring segregation incorrectly for many years—that we have actually been separating by race more and more as the years have gone by, despite the widespread belief that suburbs have diversified and urban areas have gentrified, writes Trevon D. Logan for NBC News’ THINK blog. The new paper by Logan and his colleague finds that segregation in rural areas increased as dramatically as in urban areas between the end of the 19th century and the middle of the 20th century. In other words, “blacks leaving the rural and urban South were migrating to increasingly segregated Northern cities, but the areas they were leaving behind were becoming increasingly segregated as well.” This paved the way for policies that have reinforced segregation even after it became illegal, from mass incarceration to school funding, and continue to drive us further apart. When it has been proven that personal contact with other races reduces prejudice and bias, how are we to bridge a racial gap if we are less likely to interact with each other as neighbors, Logan asks.

A recent experiment highlighted in The New York Time’s The Upshot shows that U.S. conservatives are unique in their views about why inequality exists (typically attributing wealth to merit), but at the same time are quite like their global peers in their views of how to address inequality. The study of people from around the world looked at beliefs in the differences between rich and poor—finding that American conservatives, on average, are some of the only people globally who do not believe these differences are unfair—and performed an experiment looking at redistributing income—where American conservatives acted much like the average person from another country would. This suggests that “policy preferences are not based on core philosophical differences so much as the stories that parties tell themselves about why people are rich and poor to begin with,” writes Jonathan Rothwell in The Upshot.

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Black economists are missing from the Federal Reserve and the U.S. economics profession,” by Claudia Sahm.