Neither history nor research supports supply-side economics

President Donald Trump last month awarded Arthur Laffer—father of the Laffer Curve and the godfather of supply-side economics—the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Medal of Freedom. Relatively few economists have received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Most of them could also boast a Nobel Prize in economics, and all of them had deep records of distinguished academic work or public service, neither of which pertains to Laffer.

In its announcement, the White House called Laffer “one of the most influential economists in American history.” While it’s true multiple presidents have relied on his theories to defend significant, far-reaching tax legislation all in the name of economic growth, whether he increased public understanding of economics, helped strengthen the nation’s economy, or had a positive impact on the well-being of the American people are all highly dubious.

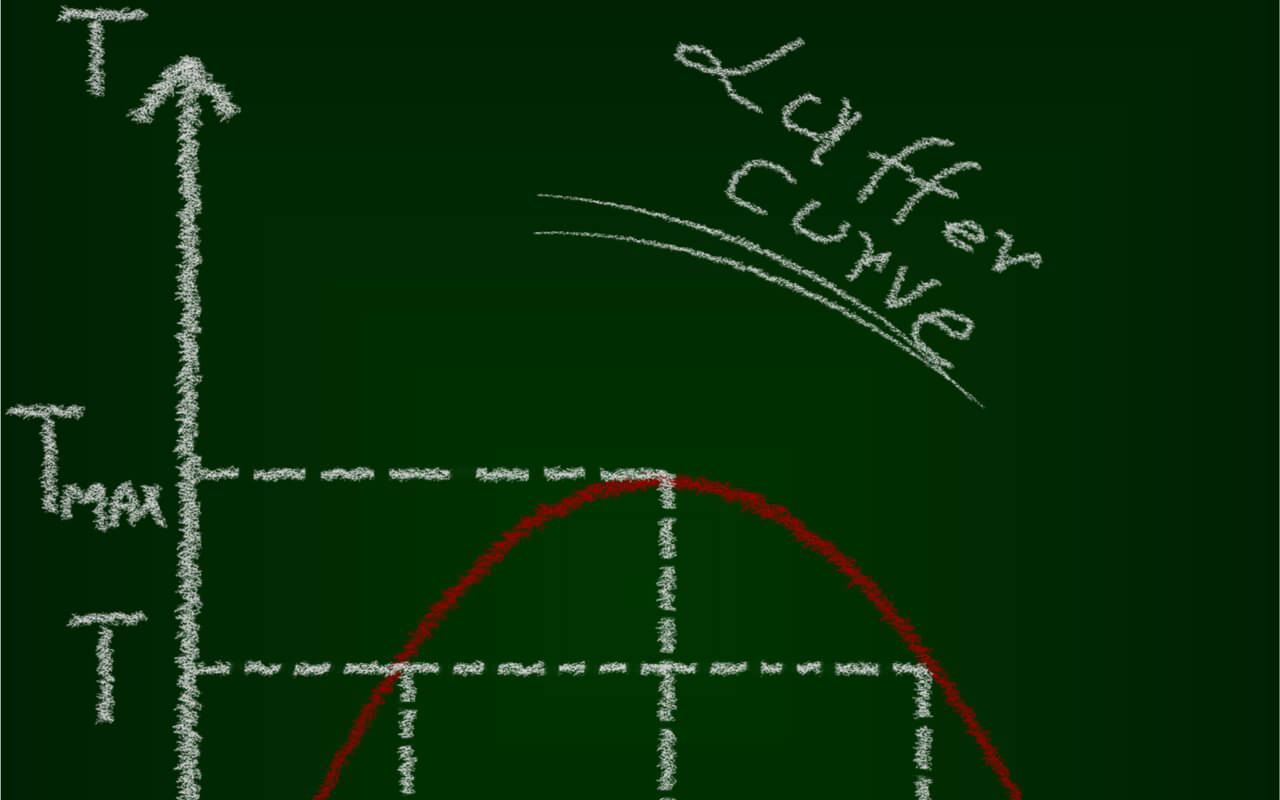

Laffer’s ideas do contain a grain of truth, in that cutting taxes can lead to more economic activity. He sold the country on the idea that tax cuts were magic. He contended tax cuts would lead to so much investment and economic growth that they would end up generating at least as much government revenue as they cost. In other words, he said tax cuts would pay for themselves.

The magical thinking sold to the American people was that giving tax cuts to the rich would improve the lives of the majority. Laffer’s theory provided a foundation for supply-side economics and was illustrated by the Laffer Curve, which he famously drew on a paper napkin for then-White House Chief of Staff Dick Cheney in the 1970s.

If the notion that cutting taxes increases revenue seems counterintuitive, there’s a good reason: It’s not supported by research. When that idea becomes the basis for government policy, it can have disastrous consequences.

We’ve seen those consequences play out over multiple administrations. President Ronald Reagan accepted the Laffer Curve hook, line, and sinker. He convinced Congress to enact deep tax cuts in 1981, and tax revenue plummeted. Despite the recovery following the recession of 1981–82, tax revenue didn’t recover and, as a result, Congress enacted deep, painful spending cuts, affecting people across the country. In order to avoid even deeper cuts to programs such as supplemental nutrition assistance and Medicaid, Congress (eventually) forced President Reagan to accept tax increases.

The Reagan tax cuts did not pay for themselves. Moreover, they ushered in a period of broad economic inequality that continues to this day.

If supply-side economics were valid, then a reasonable corollary would be that tax increases reduce revenues and increase deficits. Yet the tax policies enacted by President Bill Clinton and Congress in 1993—primarily increases in tax rates for the wealthy, along with modest spending cuts—not only raised revenues but also were followed by an economic boom that led revenues to rise so much that we saw the first federal budget surpluses in a quarter century. Tax increases, not cuts, raise revenues.

After the massive tax cuts proposed by President George W. Bush were enacted in 2001, revenue fell, with calls for spending cuts to address a self-created problem. Again, like the Reagan cuts, those tax cuts skewed heavily toward the wealthy, and, again, they didn’t pay for themselves.

Then, in 2012 and 2013, Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback, inspired by the Laffer Curve, signed tax cuts into law that were among the largest ever enacted by any state, along with significant spending cuts. Laffer was a paid consultant who lobbied hard for the plan. But the “experiment,” as Brownback called it, was an economic disaster. In 2017, the Republican legislature overrode the governor’s veto and rolled back the tax cuts.

It’s no wonder that in an editorial, The Kansas City Star said, “Recognizing Laffer’s scheme cheapens the prestigious presidential award.”

Even as Laffer’s experiment was rejected in Kansas, President Trump doubled-down on the idea. His tax-cut package, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, passed by Congress in 2017, perpetuates Laffer’s magical thinking. Again, the American people were asked to accept Laffer’s promise that deep tax cuts, which mostly go to the wealthy, spur growth and raise revenue so much so that the federal government will not have to make painful cuts. In reality, the legislation added $164 billion to the 2018 budget deficit and will end up adding more than $1 trillion to deficits, according to Congressional Budget Office estimates.

Why do these deficits matter? Two reasons. First, they show that the way to an economy with strong, stable, and broad-based growth does not start with tax cuts for the rich. Second, eventually the piper must be paid. The tax cuts Laffer’s followers put in place skewed to the wealthy, and in every instance, when revenues fell, the American people were told they needed to tighten their belts, cutting investments in people and places that undermine economic security, our nation’s infrastructure, and our efforts to grow our nation’s human capital.

To achieve prosperity for all Americans, and not just those at the top, policymakers need to look to the research. The evidence is not on the side of supply-side economics. A strong middle class with rising wages and the ability to purchase goods and services is the basis of sustainable and broad-based growth. To get there, we need policies that promote higher wages, competition, and the development of human capital, not an increasingly unequal distribution of the economic pie.

Last month’s Medal of Freedom ceremony should mark the end of the supply-side era, and usher in the beginning of a new one, where economic policies are rooted in evidence, not magic.