Overview

“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other academics to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability.

In this installment, Equitable Growth Executive Director and Chief Economist Heather Boushey talks with Atif Mian, the John H. Laporte, Jr. Class of 1967 Professor of Economics, Public Policy and Finance at Princeton University and a 2015 Equitable Growth grantee. He is the director of the Julis-Rabinowitz Center for Public Policy and Finance at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton. Mian’s work studies the connections between finance and the macroeconomy. His 2014 book, House of Debt, with Amir Sufi, finance professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business and a Equitable Growth Research Advisory Board member, builds upon powerful new data to describe how debt precipitated the Great Recession. The book explains why debt continues to threaten the global economy and what needs to be done to fix the financial system.

In a lively and wide-ranging conversation, Boushey and Mian discuss:

- The role of household indebtedness in the most recent U.S. economic recession

- The role of credit creation in economic boom-and-bust cycles

- Microeconomic perspectives on macroeconomic questions

- Economic inequality and the explosion of credit in China

- New research questions about whether low interest rates are leading to slowing economies, rising market concentration, and renewed political extremism.

[Editor’s note: This conversation took place on June 21, 2018.]

Heather Boushey: Thank you so much, Atif, for talking with me today. It’s a real pleasure to be able to talk to you about your work.

Atif Mian: Thank you for having me, it’s a pleasure to be here.

Boushey: I wanted to start with your work with your often co-author Amir Sufi. I went back and counted, and it seems to me that you have done about 15 papers together on top of a book, which seems like a lot of co-authorship. And I thought I would start by asking actually, how you guys met and how you got started working together.

Mian: Well, we met at Chicago Booth. Both Amir and I were faculty, junior faculty, there at the time. And this was in 2006, and it was the height of the mortgage boom, and that perked our curiosity, and we were discussing what was going on and why it was happening.

Our initial take was to focus on the expansion in mortgage credit toward households and approach that question from a bit of a behavioral angle to figure out why are households borrowing, what are their expectations, are they borrowing because they expect high income going forward—and so, are they borrowing to kind of smooth their consumption as traditional economic theory suggests—or is there something else going on that these people might be behaving more myopic and borrowing more than they can chew in the long term?

That’s how we got started, and we actually started working on this question before the mortgage crisis. So, the very first project we got started on, we eventually got data from [the credit reporting company] Equifax Inc., and we were probably one of the first to get credit bureau data at the individual level for research purposes. But, obviously, then the recession [of 2007–2009] happened, and it became obvious to us very quickly that this was not just an interesting question from an individual household perspective, but actually had very important macroeconomic consequences, too. And so, we quickly switched gears to focus more on the macro consequences of this behavior at the household level. And we ended up just working together since then.

The role of household indebtedness in the most recent U.S. economic recession

Boushey: Can you walk us through that research, about how debt and increased leverage made the most recent economic downturn so potent? And what in your view was the leading cause?

Mian: There’s a lot one can possibly say there, but let me try to summarize it by saying that traditionally the way economists by and large have thought about credit, and especially credit to households, is in a way that makes it a sideshow rather than something interesting by itself as a causal factor in determining macro dynamics such as aggregate demand or Gross Domestic Product. And what we discovered early on was that movements in household credit were, by themselves, potentially responsible for moving the aggregate variables such as consumption and employment. And the immediate question that raises is, why would that be the case? So, one has to then depart from the traditional framework in a sense to really make room for household credit to have an impact and a direct impact on the macroeconomic aggregates.

Now, that opens up a whole series of questions, which we have tried to address in our research. The first one is why people borrow in the first place, which goes back to the motivation of the first project that I described to you. Again, the traditional story is that people borrow because they expect higher income in the future, and they want to support consumption, so borrowing when you’re younger and expect greater income tomorrow is rational, makes sense, and we should all do that. At least that’s the standard story.

But we also know that people can borrow for other reasons. There is behavioral work that suggests households could be myopic at times, and they just borrow today because they feel that consumption today is a lot more attractive than it should be from a longer-run perspective. So, there could be behavioral reasons for people to over-borrow. And there could be other, more subtle reasons, for people to over-borrow.

So, for example, if people don’t take into account the macro consequences of their borrowing, then they could borrow collectively at the same time, which might be rational from an individual perspective but that collective borrowing leads to future problems such as a foreclosure problem that has spillovers for everyone in the economy. When people borrow individually, they may not take into account those spillovers. And so, again, from a macro perspective, people might over-borrow.

For all of these reasons, a possible result conceptually is that if and when credit expands, it is possible for households to over-borrow, to overstretch from a macro kind of social perspective. And that over-borrowing, that overstretching during the boom phase of the credit cycle, can then come back to hurt on the downside and lead to a deeper recession than it would otherwise have been.

This is one of the points we tried to make in our book, for example, based on our research that that’s essentially what happened in the United States, that the borrowing by the household sector was, in fact, a contributing factor to both the strength and the depth, as well as the persistence, of the recession that followed in 2008.

The role of credit creation in economic boom-and-bust cycles

Boushey: You also have done a recent paper with Emil Werner [an assistant professor of finance at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Business] on banking deregulation. Are you taking this research and these questions around credit and starting to look at the effects of policy changes in the short and medium term, and even the long-term effects on the increased supply of credit? Is that a sort of natural flow from one idea to the other?

Mian: That’s right. What we have found is that credit movements have a causal impact on macro aggregates, and that link works through the household sector. So, the next obvious question is, where are those movements in credit coming from in the first place? And to understand that question, we have tried to explore what we refer to as natural experiments in the past, and one of them is the wave of deregulation and liberalization of the banking sector and the financial sector over the past several decades.

The work of me and my colleagues with Emil Werner for the 1980s is along those lines, as the banking sector deregulated during the 1980s. And the usefulness of the 1980s banking deregulation experiment is that work by Philip Strahan [the John L. Collins, S. J., Chair in Finance at Carroll School of Management at Boston College] and co-authors has shown quite effectively that individual states staggered their deregulation experiment for political reasons and other reasons that did not necessarily have anything to do with where the state-specific business cycle was when they deregulated the banking sector. So, we took advantage of that sort of natural experiment, and we built on that work by looking at the more medium- to long-run impact of this credit expansion.

Now, there’s been a lot of very nice work that looked at the immediate short-term consequences of this banking deregulation. A quick summary of that work is that it led to a short-term boom. And viewed from the traditional framework, this was okay because it just shows that those areas were credit constrained, and that relaxed credit through banking deregulation led to an economic expansion. And what we argue is that all of that is absolutely true—credit did lead to a short-term credit expansion—but, equally importantly, we show that it ultimately led to a stronger recession in 1990 and 1991 as well. So, in other words, it suggests that while credit can have short-term positive impacts, there is a tradeoff to think about, which is that it can lead to an ultimately stronger downturn. That essentially means that credit can generate an amplification of the cycle, both on the upside, as well as on the downside.

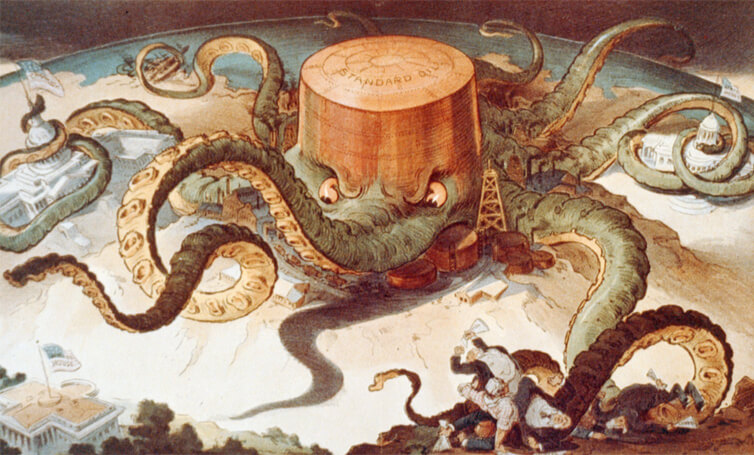

If you think of this question again from a conceptual perspective, it suggests that some of those earlier ideas that [economic historian] Charles Kindleberger and [monetary theorist] Hyman Minsky, among others, had been talking about perhaps in a more descriptive sense are very much relevant for us to consider when we are thinking about the role that the financial sector plays in the macro economy. And this, in turn, obviously has implications for policy, for prudent macroeconomic policy, as well as for the collateral damage effects, if you like, of deregulation and liberalization.

One of the longer-run questions goes even a step deeper than just talking about deregulation or liberalization. And that is, credit in the macro economy is not just a story about business cycles, but also about what I sometimes refer to as a super cycle, or a secular trend in the background, which perhaps is even more important than the ups and downs of credit in a 3- to 4- year horizon. And that longer-term trend, or the super cycle, is that since 1980, we have seen a large increase in credit to GDP across the board. This is not just a U.S. story. It’s not just a European story. It’s also really a global story. Credit has expanded at an incredible pace and is currently at a level never seen before, historically speaking.

Along with this massive expansion in the quantity of credit, there has been a related decline in the price of credit. And here, I’m basically referring to the decline in long-term interest rates since the 1980s. This is the super cycle I was referring to, and if you just put these two facts together—an expansion in quantity of credit and a reduction in the price of credit—then basic Economics 101 would suggest that if quantity is expanding and price is declining, then in the background there is something like a supply expansion, right? The supply side of credit has been expanding, it seems, based on these basic facts.

And, again, the question is why. Forces such as deregulation and liberalization are good at explaining the short-term movements that I just described during the 1980s in the United States, but those forces are not very useful in explaining these very persistent, longer-term massive increases in the quantity of credit. Deregulation and liberalization might themselves be a consequence of a deeper fundamental force behind the financial sector. And that’s something that my collaborators and I have more recently been trying to figure out. Why has credit over this longer term expanded?

This is where we feel there is a connection between what has been happening in the financial sector and some of the more fundamental shifts in the global economy. In particular, I’m thinking about economic inequality, the rise of concentration of market power, as well as some of the institutional dimensions such as the rise in China and the extremely high saving rates in China for various reasons, one of them having to do with the kind of centralized nature of economic power within China. We are now exploring if these movements in inequality are themselves responsible for this massive expansion in the financial sector.

We have a new paper that suggests that there is empirical evidence to support this argument. And that argument basically is the rise in inequality, which is by and large a top 1 percent phenomena, with the top 1 percent globally expanding their share of the pie. The other thing we know about the top 1 percent is that it tends to have very high saving rates. So, the marginal propensity to save for the top 1 percent is persistently extremely high relative to the average propensity of the population.

And so, if you put these facts together, the natural implication is that the rise in inequality will increase gross savings in the global economy. Now, the thing about gross savings is that when people save, they essentially channel that money through the financial sector. And so, they leave it to the financial sector to decide where those savings go. And what has been happening globally is that this increased flow of savings coming into the financial sector has naturally led to the creation of credit because that’s what the financial sector does.

Now, in order to absorb these ever-increasing amounts of credit, something else needs to give. You need to convince people to borrow more one way or the other, and one of the ways or mechanisms through which this has been happening is through this continual reduction in the long-term rate of interest. The global economy can afford to borrow more and more if interest rates keep going down.

Just imagine an interest rate of zero. At an interest rate of zero, you can have an infinite amount of debt if you want it. Because you can just keep rolling over the debt that you have at no cost since the interest rates are zero. This same logic basically applies before you hit zero as well. This is one explanation of what has been happening globally.

Now, this has very deep and important implications for how we should interpret what has been happening in the financial sector, and also in terms of some of the policy implications about what needs to be done in the long term to really address this problem of over-levered economy. And that’s something my colleagues and I are thinking about more carefully going forward.

Boushey: Well, if it is true that a big part of the rise in credit is connected to the rise of inequality globally, as you so compellingly lay out, then it does pose real questions for policymakers. What I take from that is that we need to do more thinking about the role of inequality in not just the micro outcomes that I think we’ve thought about for a long time, but also the macroeconomic outcomes, which have not really been on the table as much. It’s been hard to find research and scholarship that puts that front and center, and then what you would do about it would generate some new questions.

Connecting the microeconomic perspective to macroeconomic questions

Boushey: One of the exciting things about your work as I’ve followed it over the years is that you are bringing this microeconomic perspective to macroeconomic questions. This seems to me to be an important contribution to the field. Tell me a little bit about where you see this work fitting into the larger questions in financial macroeconomics and what some of these big questions are.

Mian: Let me say something positive first and then something negative about macroeconomics as a field. The biggest attraction for me when thinking about macroeconomics is that this is the field that has the most important and exciting questions. Why do economies grow? Why do they collapse at times? Why do people remain unemployed? These are fundamentally important questions that everyone on the street is interested in. And this is what makes macroeconomics most exciting in my view. That’s my positive spin on macroeconomics.

The negative is, in a sense, also driven by the positive, and is that since macroeconomics is a study of the aggregate economy, the aggregate dynamics, it essentially suffers from this one observation problem, which is that you only get to see the whole economy once. How much can you deduce from observing that one realization of that economy, that one time series, that one time when the U.S. economy sometimes goes up, sometimes it slows down, and so on?

We have a number of different explanations for what might be causing those booms and busts, what might be causing some countries to grow more aggressively than others. But our number of theories is much larger than the number of observations we have, which is a limiting factor of macroeconomics just from an empirical standpoint. So, this is where I feel micro data comes in, which is that it allows us to open up this space by giving us, in technical terms, a lot more degrees of freedom. And that can be used fruitfully and intelligently if you keep the theories in mind as you dive deeper into the more micro level of granular datasets.

That’s the first advantage that micro-level datasets allow you to do, which is to tease apart the various theories that might be behind the macro dynamics in a way that you could not do without the micro-level data. Let me just give you one quick example. I mentioned earlier that you can observe growth in credit, and ask what is behind that? This is something that the Fed and [former Fed Chair Alan] Greenspan were openly thinking about during the 2000s. If you just look at the aggregate data, you see credit going up, you see aggregate income going up as well, and you can ask yourself the question: What is the reason credit is going up related to the fact that incomes on average are going up as well? And you might conclude from the aggregate evidence that, yes, that’s what’s happening because both variables are increasing at the same time.

But when you look at micro-level evidence, you might not come to the same conclusion because it depends critically on who is borrowing. And so, is it that the top 1 percent is borrowing as much as the bottom 99 percent, or even more than the bottom 99 percent? If it were higher incomes that were driving credit growth, then since income growth is concentrated in the top 1 percent, we should really expect the top 1 percent to borrow a lot more.

Boushey: Right.

Mian: Yet that clearly was not the case. So, even a basic breakdown of the data along a more micro level starts to give you a lot more insights than you might be able to deduce from just looking at the macro aggregates. That’s the first advantage of looking at more granular data. It allows you to parse through the set of theories that you otherwise have that are difficult to separate by just looking at the time series aggregates.

The second advantage of micro-level data is that it really highlights some of the key factors that we need to incorporate in our theoretical models to make them more realistic. Let me just point out one important element that has come out as a result of work not just by me and my colleagues, but a number of other people as well, using this more granular micro-level data for answering macro questions. Historically, a lot of the macro modeling had been done using your present division household, which has been extremely useful putting a framework around our thinking, but what the micro-level evidence really suggests is that heterogeneity across households is really important if you want to understand aggregate dynamics.

Now, it’s not just heterogeneity in general. Obviously people are different. What we have realized is that heterogeneity along the dimension where credit operates—and in particular heterogeneity across borrowers and lenders, or savers and borrowers if you like—is that those two sets of households are really different. And that really allows us then to connect finance to the macro economy in a way that is much more based in actual data.

Because borrowers and creditors behave very differently to shocks such as house prices going up or down, to expectations about the economy and so on, that naturally lends itself to a view that finance and financial shocks are really important for the macro economy because if there is an expansion in credit, well, guess what, by definition, credit is going to be received by people who tend to be borrowers. And so, if they respond much more aggressively to a house price increase, then that’s going to have a much bigger impact on the macro economy as opposed to a similar period where house prices are going up on average but credit is not expanding at the same time for one reason or another. Understanding the importance of heterogeneity is something that has come about because of the proliferation of micro-level data in the past 10 years.

Economic inequality and the explosion of credit in China

Boushey: It’s been so exciting to see these new ideas filtering their way through economics from where I sit at the more policy end of it. Well, we’re running out of time, so I want to ask you one more question. Equitable Growth has a competitive grants program. We fund academic research from scholars all across the United States, including you and your colleagues. So, I would like to end our conversation today by asking you what are the big important questions or trends that we need more research on? Where’s an area that you think could use some more attention, could use some more support, or where there needs to be more work?

Mian: Well, first of all, thank you for the support, and not just for us but also to the wider academic community. I think this is an important point that needs to be recognized explicitly as often as we can, which is the social value of funding research.

The most successful societies, in my mind, are societies that have the capacity to analyze themselves. And that’s really what research is trying to do, to analyze the economy, the society, the political economy around us. And institutions such as yours are extremely important and instrumental in making that happen. So, thank you for all the work that you and your colleagues do.

In terms of interesting research or questions, we’ve talked about credit and the macro economy, and as I mentioned, the really important question is not just the fact that credit appears to affect the macro economy, but more importantly where does credit come from in the first place? And what does it really mean?

This raises the question about inequality. But the other angle that this line of work suggests is that the global economy has been suffering from lack of demand over time, and in order to solve that problem through the markets, through policy responses, and so on, the way we have tried to solve that problem is through more credit creation. And you see that in some places very clearly. China is an excellent example. The country is relying on the rest of the world borrowing to buy its goods and services. Post-2008, that was not possible to the same degree because the rest of the world—the United States in particular—stopped borrowing at the rate that they were borrowing before.

And so, China had to adjust internally and domestically. China had to generate the demand domestically. And guess what happened? China went through an enormous credit boom and is still going through an incredible credit boom at a pace that we have essentially never seen before. The research question is, what’s really behind that? There is a more fundamental force that’s driving all of this behavior, and those forces are extremely important to understand.

New research questions about whether low interest rates are leading to slowing economies, rising market concentration, and renewed political extremism

Mian: A related thread that I would like to mention is that because lower and lower interest rates are needed to sustain a higher level of credit globally, there’s a very important question of what happens in that kind of environment. What are the consequences of a very low interest rate environment, not just locally but globally, and not just for a short period of time but for a sustained period of time?

This is a question that I don’t think has received as much attention. We just have this tendency to take interest rates as given and use that as a price that equilibrates the markets, so to speak, and take it as a given. I think there is an interesting and important question of what are some of the consequences of low interest rates on the economy.

My colleagues and I have a new project where we’re exploring that question. The angle we’re taking is trying to understand if low interest rates have an impact on the strength of competition within an industry. In particular, could it be the case that low interest rates actually promote monopolization of industries and sectors? This would link interest rates back into the supply side of the economy. And that’s just one question or angle that we think is worth exploring more. There’s a lot more to think about here.

Along the same lines—and this is related to everything I’ve talked about—is this question of this slowdown in productivity growth or slowdown in growth more generally. When you combine slow productivity growth with this increased inequality and increased monopolization or reduction in competition globally, that raises a number of very important political economy questions. Anyone who reads the news globally knows this is a first-order thing, right? And to what extent are these economic forces responsible for some of the political economy shifts that have happened globally, among them the rise of extremism of various sorts all over the world, which is extremely troubling for anyone who values basic human values or the liberal democratic order?

What we are observing is this pent-up anger, this level of social unrest or discontent with the status quo institutional arrangements that exist today. I think that does raise some very important questions about how we decide to organize our financial markets, how we decide to organize economic institutions, and whether these things have been done the right way, or is it the case that some of this discontent is a result of us ignoring the distributional dimension of these policies?

There’s a lot here, obviously. This is a loaded set of questions that I’m raising here. But I think understanding these connections methodically, one by one, it’s extremely important. And it’s also extremely important that we do all of this in a very objective manner in this world where people are becoming more and more or polarized and ideological. The other beauty of research is if you can stick to that integrity, if you can approach all of these questions from an objective, data-driven process, then you can figure out what is really the reason things are happening the way they are happening and what we can do about it.

Boushey: Thank you. That is a lot and gives us a lot of guidance for how we should be thinking about our work here at Equitable Growth. I will certainly be taking all this into consideration. Thank you so much for your time. It’s just been a real pleasure.

Mian: You’re welcome.

Related

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!