On Juneteenth: New research demonstrates how economic mobility is restricted for Black Americans

On June 19, 1865, emancipation was officially declared in the state of Texas, more than two full years after the Emancipation Proclamation and more than two full months after the pro-slavery rebellion was defeated in the Civil War. This day, thereafter called Juneteenth, marked the real end of the juridical and economic system of slavery in the United States, but in reality the political struggle for freedom continued and continues to this day in new forms.

Tomorrow, we celebrate this emancipation. But it is also a time for reflection on the legacies of freedom deferred.

To mark the day, we are highlighting some recent research on the state of economic mobility for Black Americans. While not an exhaustive list, these studies demonstrate both the long history of the aftermath of slavery and the persistence of racial inequality that continues to shape the U.S. economy and society.

New findings on restricted economic mobility for Black Americans

Two recent studies utilize new methodological innovations to examine the relationship between economic mobility and racial inequality, helping to shed light on the different ways mobility is continually restricted for Black Americans.

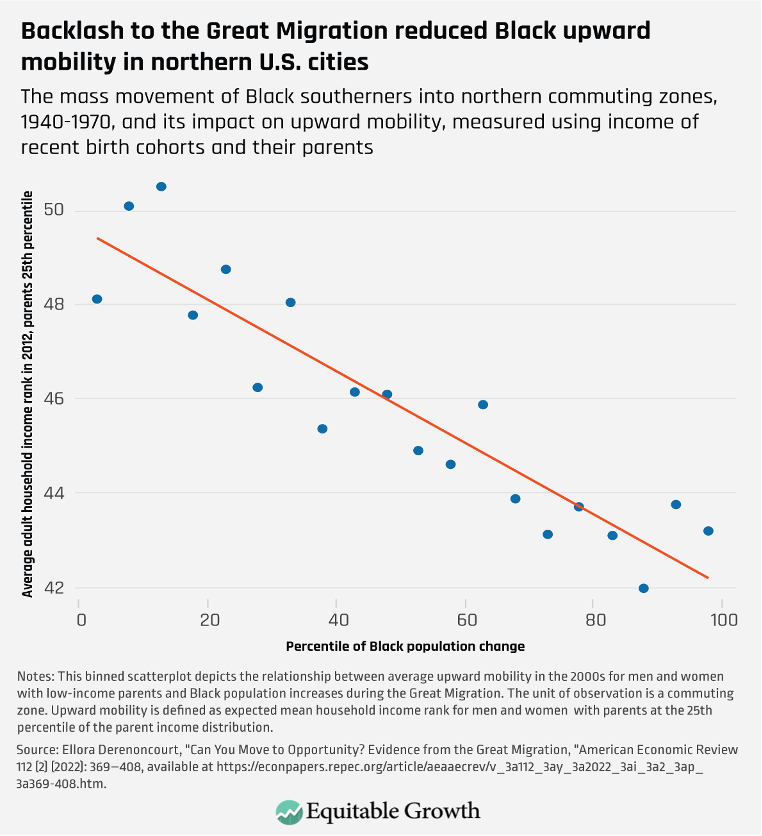

A 2022 working paper by Princeton University economist Ellora Derenoncourt analyzes the impact of the Great Migration of Black Americans out of the South in the early to mid-20th century on the future generations of these migrants. She constructs a novel database using several large data sources, including data on local government expenditures, private schools, crime, incarceration, and other variables spanning the period 1920 to 2015, as well as assembling U.S. Census data from 1900–1940.

Derenoncourt finds that the gains accrued by the first generation of Black Americans during the Great Migration dissipated with future generations. In fact, by the third generation, she finds that Black Americans whose grandparents migrated from the South to the North in the early 20th century have the same or worse economic outcomes as Black Americans whose grandparents did not move away from the South.

Derenoncourt explains that this erosion is due, at least in part, to backlash to the Great Migration, including racial terror, in Northern cities, where segregation was entrenched through White flight to the suburbs and public investments were siphoned from social infrastructure to policing.

According to Derenoncourt, without this backlash, the Black-White mobility gap would be 27 percent smaller. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Moreover, economist Randall Akee of University California, Los Angeles, and the U.S Census Bureau’s Maggie Jones and Sonya Porter employed a new research strategy to analyze the trend of increased income inequality and decreased mobility by examining differences between and within racial and ethnic groups. The authors created a novel dataset using administrative tax data linked at the person level and Census Bureau data on race. This unique method enabled Akee and his co-authors to overcome limitations that previous research on mobility and race experienced, such as small sample sizes, as well as other general limitations with survey data.

As a result, the authors find significant income stratification by race and a generally fixed income distribution over time. Specifically, from 2000 to 2014, all the groups the authors examined experienced higher levels of within-group inequality over time. White and Asian Americans experienced the highest levels of intra-group inequality and the lowest levels of intra-group mobility. The opposite was true for Black, American Indian, and Hispanic Americans, all of whom experienced low within-group inequality and high within-group mobility.

Yet the authors find that the latter three groups have the lowest levels of intergroup, or overall, mobility across different groups within the U.S. population and the highest probability of downward mobility, relative to White and Asian Americans. The findings paint a picture of a calcified income structure in which Black, American Indian, and Hispanic individuals are persistently clustered at the lower end of the income distribution, while White and Asian Americans tend to be on the higher end.

New research on racial disparities in access to income supports

While there are numerous mechanisms restricting economic mobility for Black Americans, the COVID-19 pandemic recession—and the policy responses to it—provided an opportunity for researchers to analyze a specific factor: the current system of income support programs.

In the United States, income supports are a standard, though inadequate, means of addressing some of the consequences of entrenched economic inequality and precarity. These programs help ensure that U.S. households have the income they need to cover their basic expenses, either in the form of direct cash transfers (such as with Temporary Assistance to Needy Families or Unemployment Insurance) or by providing essential goods (such as food or housing) to families, freeing up income to be used for other necessities. Unemployment Insurance, for example, provides direct support for workers during times of economic distress, ideally mitigating the loss of income during downturns and the long-term harm of unemployment on economic well-being and mobility.

Yet racial inequities in accessing these programs persist, which can result in further restricting the mobility of Black Americans. This was no different amid the COVID-19 recession, despite emergency funds and temporary expansions of several income support programs to mitigate the effects of the recession.

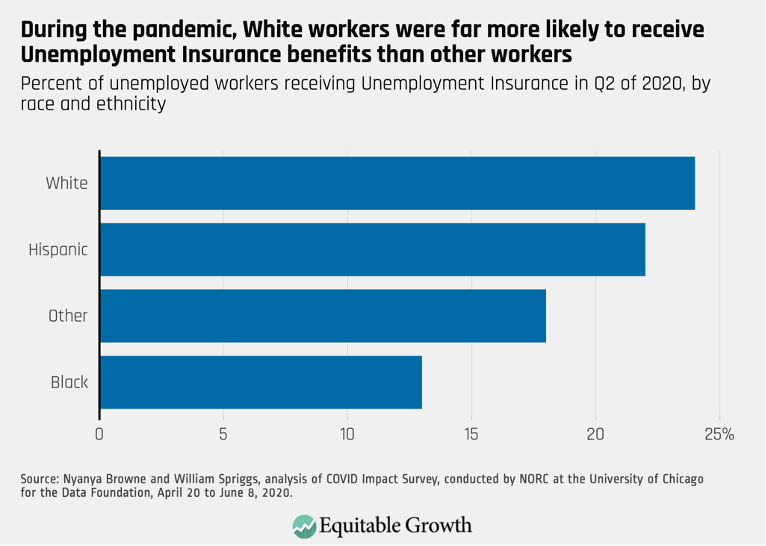

For instance, economists Eliza Forsythe and Hesong Yang of University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign find that disparities in receiving UI benefits by race persisted despite expansions to Unemployment Insurance through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act in 2020. As a percentage of eligible recipients Black UI-eligible workers were less likely to receive benefits than White UI-eligible workers by as much as 8 percentage points.

Other recent research examining the COVID-19 recession confirms the persistence of racial disparities in receiving UI benefits. In an analysis of survey data between April 2020 and June 2020, economists Nyanya Browne and (the late) William Spriggs of Howard University find that Black workers were approximately half as likely to receive UI benefits as White workers, with 13 percent of Black workers receiving such benefits, compared to 24 percent of White workers. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

To be sure, racial disparities in UI recipiency are longstanding, and these discrepancies prior to the COVID-19 recession are well-documented. For instance, in an analysis of data from 1986 through 2015, economists Elira Kuka of George Washington University and Bryan Stuart of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia find that Black workers were 24 percent less likely than White workers to receive UI benefits.

In addition to racial inequities in accessing Unemployment Insurance, there are also longstanding gaps in the amount of UI benefits received. Economists Daphné Skandalis of the University of Copenhagen, Ioana Marinescu of University of Pennsylvania, and Maxim N. Massenkoff of the Naval Postgraduate School studied the UI replacement rate, or the unemployment benefits received relative to prior earnings. They find in their analysis of 2002–2017 data that the UI replacement rate over that period of time was 18.3 percent lower for Black claimants than White claimants.

When examining the factors contributing to this gap, Skandalis and her co-authors find that after adjusting for work history, which can impact prior earnings that need replacement and the likelihood of losing one’s job, the replacement rate for Black claimants was 8.4 percent lower than White claimants. This gap is due entirely to differences in state rules concerning Unemployment Insurance.

The authors also find that the share of Black UI claimants is negatively correlated with the amount of UI benefits. Their analysis finds that weekly UI benefit amounts decrease by $9 for every 10 percentage point increase in the share of Black UI claimants.

Conclusion

Juneteenth offers a chance to celebrate the end of slavery and also to reflect on how far we still have to go to achieve fairness and equality in the United States. These recent studies illuminate the many ways in which racial inequities persist in the U.S. economy, hampering economic mobility for Black Americans and reinforcing longstanding income and wealth inequality.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!