AP Images

About the author: Till von Wachter is a professor of economics and the associate director of the California Center for Population Research at the University of California-Los Angeles.

The Unemployment Insurance system provides temporary and partial earnings replacement for workers that have become unemployed through no fault of their own and are actively searching for work. To facilitate reemployment, the UI system is complemented by job search assistance and training services. Within a common federal framework, states set the main parameters of the UI system and are responsible for financing benefits via payroll taxes, though federal funding has played an increasing role, especially in economic downturns.

In the United States, and most other developed countries, unemployment insurance is the main program helping to buffer the shock of layoffs and unemployment. The UI system provides vital benefits for laid off workers and families to weather the high and persistent costs of layoffs, especially in recessions. By preventing cuts in consumption, UI benefits can also function as an automatic stabilizer in economic downturns. Given high layoff rates even in normal economic times, the insurance provided by UI also plays an important role by supporting a well-functioning, dynamic labor market.

The need for common sense and

evidence-based unemployment insurance reforms

While most observers agree that the current structure of the unemployment insurance system is fundamentally sound, there is also widespread agreement that the UI system is in need of reform. There are several major issues to be addressed, First, the current UI system suffers from financial instability that risks compromising its major role as adjustment mechanism in recessions. Second, the coverage of UI has eroded over time, with a declining fraction of workers receiving lower benefits amounts. Third, UI does little to avert the large, long-lasting earnings losses among reemployed workers. And fourth, there are persistent questions about the effectiveness of UI and related programs to quickly reemploy job losers.

The good news is that, in many ways, unemployment insurance appears to be an ideal target for bipartisan reform. First, there is a set of straightforward, common-sense goals for a well-functioning UI system. These goals include, among others: that UI should provide a sufficient buffer to avoid financial difficulties after layoff, especially for families with children; that UI should encourage speedy reemployment of the unemployed; that UI plays a clear role in economic downturns, and hence should not be at the discretion of local or federal politics; and that UI should be financial sound.

Second, Unemployment Insurance reform is an almost ideal example of the potential for evidence-based reform. There is a lot of high-quality evidence on the working of the UI system. A lot of the additional evidence needed for more-informed policymaking can potentially be obtained at arm’s length, especially in a data-rich environment. The following “primer” discusses and summarizes core pieces of recent evidence on job loss, unemployment, and the current UI system, and then relates them to a series of reform proposals. The reform proposals can be grouped into those that deliver a basic “tune up” of the current UI system, and those that provide more fundamental “modernization.” These are summarized here:

“Tune-up” (minimal) reforms:

- Prevent erosion of benefit generosity by mandating minimum UI benefits

- Institutionalize federal emergency unemployment compensation

- Fix outdated system of data collection to enable evidence-based policies

- Expand coverage of UI to fit structure of modern workforce

- Resolve financing short-falls in states’ UI trust funds by modifying tax base

Modernization reforms:

- Institute functioning system of job sharing to prevent costly layoffs

- Experiment with wage insurance to aid workers returning to employment

These proposals will be related to the issues they resolve and the evidence they rest on after a brief primer on the main available evidence about the UI system.

A primer on evidence about

the Unemployment Insurance system

A few key themes arise from extensive research on core aspects of the Unemployment Insurance system. While additional research is needed, the good news that the much of the data needed is potentially available at low cost from the UI system itself.

Point 1: The current benefit levels and durations appear appropriate. An increasing number of studies have shown that current Unemployment Insurance benefits provide an important buffer against consumption losses for a substantial number of unemployed workers. While a large number of studies have established that UI also tends to prolong unemployment and hence reduce tax revenues, it appears at current levels that the social benefits outweigh the budgetary costs. Recent research also gives clear guidance that UI benefits should be extended in recessions, and when they should be targeted to certain groups of individuals.

Point 2: The coverage of Unemployment Insurance has eroded over time. It is well known that on average only half of the unemployed receive UI benefits, substantially limiting the program’s scope to insure individual earnings shocks and provide an automatic stabilizer. This is partly because up until recently UI rules in most states explicitly exclude certain groups of unemployed—those engaging in full- or part-time education, those seeking part-time employment, or those with low earnings. Partly it arises because of a low take-up rate of benefits among those eligible.

Point 3: The effects of layoff are felt long after unemployment. An increasing amount of evidence suggests that the effects of job loss are felt long beyond reemployment, including effects on earnings, health, and child outcomes. Children of job losers suffer from the consequences even as adults. Overall, research suggests UI benefits only make up a small portion of the earnings lost at job loss.

Point 4: Current reemployment efforts show mixed success. While many programs aiming to aid Unemployment Insurance recipients to find work are successful and sometimes cost-efficient, increasing evidence suggests that substantial hurdles for successful reemployment remain, especially for older and longer unemployed workers. Especially for these individuals, longer UI benefits do not improve and may even reduce job quality. Although the evidence is mixed, an ongoing concern is UI may damage reemployment prospects by lengthening the unemployment spell.

Point 5: The federal-state relationship needs to be fixed. Although in principle the nature of Unemployment Insurance taxes should lead state UI trust funds to balance over the business cycle, reductions in UI tax rates and a low tax base have led to financing shortfalls. As a result, benefit extensions during recessions have been increasingly financed by ad hoc federal measures. To partly resolve budget short falls, several states have begun cutting benefits. Currently, political constellations at the state level have led to a patch-work of UI reforms, exposing similar workers to different UI systems. The current system also suffers from a wasteful lack of data-sharing that prevents meaningful management and study of the UI program.

Proposals for “tune up” (minimal reforms)

of the Unemployment Insurance system

Policy analysts and researchers have discussed the need to modernize the unemployment insurance system for some time. This discussion received momentum during the Great Recession. The result has been a series of well-articulated proposals, and convergence on a list of basic fixes. Several of these reform proposals have made it into President Obama’s Budget Proposal for fiscal year 2017, which begins in October 2016. The following is a list of the core proposals, including a brief summary of their justification.

Prevent erosion of benefit generosity by mandating minimum duration of 26 weeks

The issues. Partly to counter funding difficulties in the aftermath of the Great Recession, several states have cut benefit durations below the typical 26-week mark. Similarly, there is substantial heterogeneity in benefit levels across states. Yet, there are no compelling reasons why similar workers in different states should be treated different by the Unemployment Insurance system. Research provides justification for the optimal generosity of UI benefits, and when these should vary with characteristics of workers or local labor markets. Hence, the choice of benefit parameters and how they vary in the population or over time should not be a function of the local political process or short-term funding needs.

Proposed changes. Federal law should mandate a minimum amount of potential duration of Unemployment Insurance benefit of 26 weeks, an average effective replace rate of 50 percent of benefits (with gradual adjustments of the maximum benefit amount), and a dependent allowance to support families with children with higher consumption commitments. To ensure states update their laws, the federal government can limit the credit for the State Unemployment Tax employers receive against the Federal Unemployment Tax.

Institutionalize federal emergency Unemployment Insurance benefits as function of local unemployment

The issues. Research clearly indicates that Unemployment Insurance benefits should be extended in recessions. This is because the benefits to workers at risk of exhausting their benefits are greater, the inefficiency costs are not larger and perhaps smaller, and the potential of stimulating effects is greater. The experience in the aftermath of the Great Recession has shown that leaving extensions of UI benefits to the political process can lead to gaps in coverage that are damaging to affected workers. For most recessions, there is no evidence indicating a need for wasteful and potentially harmful discretion.

Proposed changes. The federal Emergency Unemployment Compensation program should be made a permanent program. A straightforward way to achieve is to reform the current Extended Benefit program and make it 100-percent federally financed. In the course of such a reform, the trigger structure should be modified to keep the fraction workers covered by UI approximately constant over the business cycle.

Fix outdated system of data collection to enable evidence-based policies

The issues. To maintain daily operations of their Unemployment Insurance programs, states collect information on workers’ wages, UI claimants’ benefits, and their employers’ UI taxes. This information is vital for an efficient administration of the UI system, including understanding which parts of the system are cost effective. Yet the current law only requires states to share the data with federal agencies for extremely limited purposes. Moreover, many of the data sets lack basic information, such as on worker age or gender. Ample experience now exists to cheaply handle and combine sensitive administrative data.

Proposed changes. The data collection should be modernized by adopting four complementary strategies: enhance data collection by states; establish a national data clearinghouse of Unemployment Insurance data at either the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics or the U.S. Census Bureau; support these changes by providing a common software and offering moderate grants for upgrade hardware; and establish a protocol to allow to access the data for research purposes and to improve the UI system. It is important to include an enforcement mechanism to ensure states’ compliance with this requirement.

Expand coverage of Unemployment Insurance to fit structure of modern workforce

The issues. The current Unemployment Insurance system does not serve a large fraction of the unemployed. This is partly due to changes in the structure of the workforce, with increasing amounts of low-wage workers in unstable jobs or rising part-time employment especially among women. Through incentives provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a substantial number of states have now made benefits more easily accessible by adopting a range of proposals.

Proposed change. A reform should provide pathways to harmonize eligibility for Unemployment Insurance across states and increase take-up rates among eligible individuals. There is little justification for the current patchwork of eligibility, and meetings of state and federal UI officials should provide a system of best practices for eligibility requirements and outreach. Eligibility requirements should include those proposed in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, among them allowing for training of UI beneficiaries, enabling part-time workers to claim benefits, enhancing the mobility of working couples by making moves for family-related reasons a qualifying event for UI, and instituting the alternative base period. In addition, some of the gradual restrictions imposed over the last three decades to lower UI payments should be reviewed and possibly modified as well.

Resolve financing short-falls in states’ UI trust funds

The issues. As a consequence of growing wages (and hence benefits) and low taxable wage bases that are not indexed to covered wages, just 25 percent of earnings covered by Unemployment Insurance laws nationally are currently subject to state UI payroll taxes. The minimum taxable wage base, set by the federal government, is currently $7,000 and has not changed since 1983. Similarly, the net federal tax rate—as defined under the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, or FUTA—has been 0.8 percent for more than 30 years, depressing revenues that pay, among others, for UI administration by federal and state agencies. Many states’ UI taxes—as defined by their State Unemployment Tax Act, or SUTA—have remained low as well, and states have increasingly resorted to borrowing to finance UI benefits in recessions. Hence, even without the large increase in UI payments during and after the Great Recession the financial soundness of the UI system was steadily eroding.

Proposed changes. Several sensible reforms of the complex financing system have been proposed. One is to raise the federal taxable wage base, index it to wage growth, and correspondingly lower the FUTA tax rate. Another is to institute federal penalties for states that fail to carry sufficient forward balances in their trust funds during expansions. And a third is to prevent payroll taxes from rising in the midst of a protracted recovery by extending the 2-year window until FUTA tax credit expires, institutionalizing interest wavers, and encouraging states to also delay automatic tax triggers aimed at balancing their trust funds.

Additional proposal worthy of consideration but not discussed further here

There are additional interesting proposals meant to fix additional shortcomings of the current unemployment insurance system. In addition, there are challenging open questions that have not yet been addressed. These proposals and open questions include, among others:

- A modernization of the administration of Unemployment Insurance, including information technology used to administer claims, which is found to be often outdated and underfunded by the federal government

- A reform of firms’ UI tax rates to better internalize the costs of layoffs, reduce the cost to the UI system, and achieve similar cost of layoffs across states

- An optional private unemployment account to cover the self-employed or independent contractors

- A “job seeker allowance” to aid young workers not qualifying for UI because of a lack of earnings history

Proposals for innovation of

the Unemployment Insurance system

Even if sufficiently modernized according to these basic reforms, Unemployment Insurance as it is currently designed can neither prevent nor buffer much of the large and lasting earnings losses due to layoffs. This also affects the UI system’s efforts to reemploy workers, who may wait too long to engage in the long process of rebuilding their careers. Yet several innovations of the existing UI system have been proposed that could greatly expand the reach of UI without the need to establish a new program.

Institute a functioning system of work sharing to prevent costly layoffs

The issues. An increasing number of U.S. states have instituted programs of work sharing—also called short-term compensation, or STC—that allow workers to draw pro-rated UI benefits while on the job as an alternative to layoff. Evidence from other countries suggests work sharing can achieve substantial reductions in layoffs. Yet, take-up of the programs by employers in the United States has been low, partly because of restrictive program rules and partly because of a lack of awareness about the program.

Proposed changes. Several policy options are available to strengthen the use of STC across and within states, especially during recessions. One would be to continue to incentivize adoption of the program, with 100 percent of STC outlays funded federally for the first three years after adoption, or alternatively require states to establish STC programs. To raise attractiveness to employers, during this period states should be required to not charge employers for their uses (meaning there should be no experience rating). Another policy option would be to encourage states to share best practices and harmonize their efforts in outreach, and consider targeting employers using industry-level indicators of economic activity or those in the WARN system. A third policy option would be to encourage widespread use of short-term compensation during recessions when Extended Benefits are turned on by having STC benefits 100-percent federally financed; by suspending experience ratings; and by not having STC benefits deducted from workers maximum UI eligibility. Finally, research should continue to assess what prevents adoption of the STC program, and best practices for eligibility requirements should be developed.

Experiment with wage insurance to aid workers returning to employment

The issues. Since Unemployment Insurance only insures a minor fraction of the total earnings risk of job losers, its role as insurance mechanism and automatic stabilizer in recessions is substantially below potential. As a result, a growing number of researchers have suggested complementing the current UI system with a system of wage insurance. Wage insurance is likely to provide substantial additional insurance value. In addition, it may provide cost-savings by lowering UI payments. And it is unlikely to further reduce wages, and may raise them by shortening unemployment. Yet, currently little is known on potential effects of wage insurance.

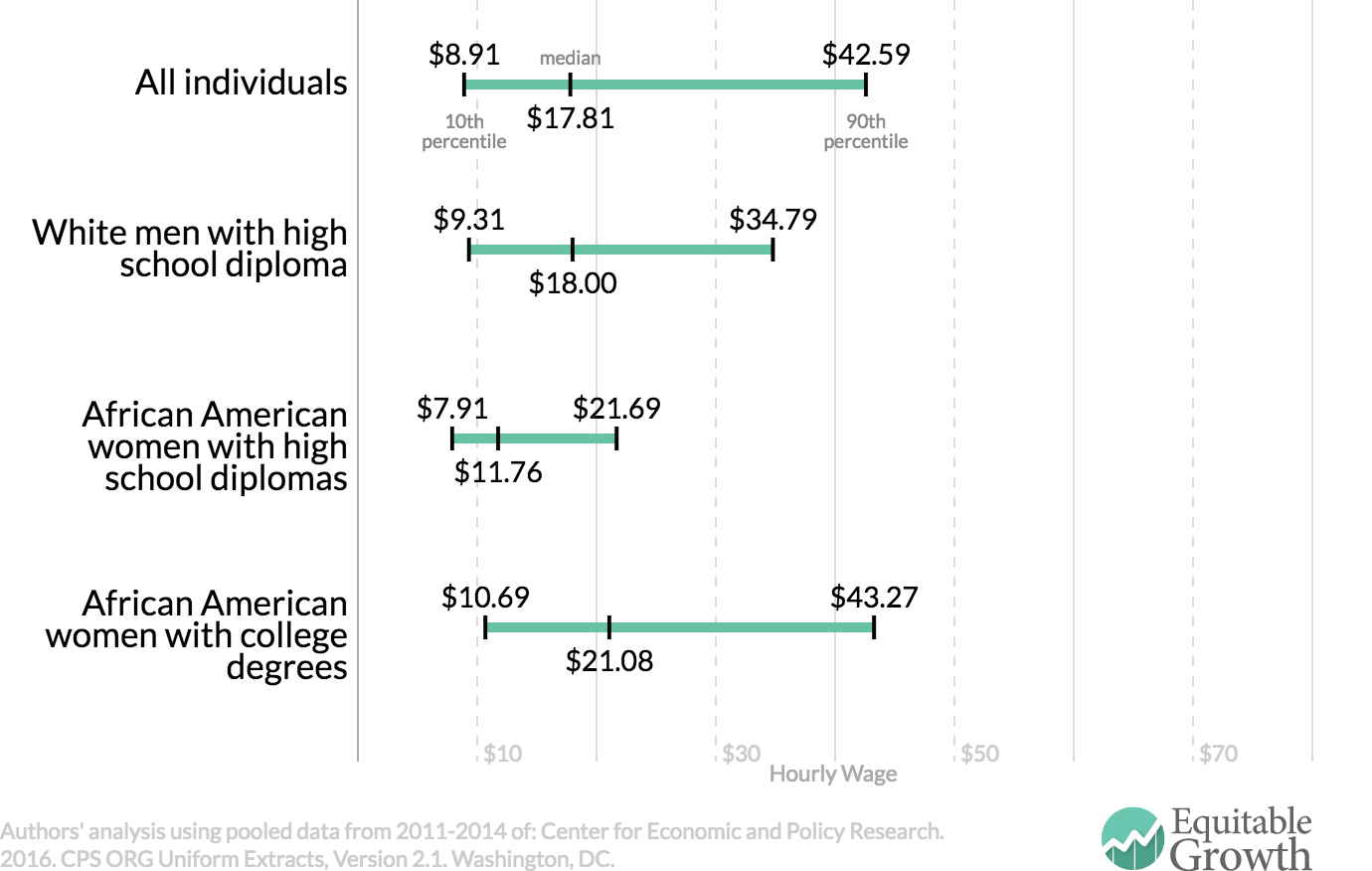

Proposed changes. A series of proposals have been made to extend existing wage-insurance plans for trade-related layoffs to all workers covered by Unemployment Insurance. Given the evidence on job loss, introducing a version of wage insurance is sound policy, but an experimental evaluation will be important to better understand the effects. Policy parameters should be set with core facts in mind—for example, average wage losses of displaced workers with three years or more of tenure from good employers in a recession are about $15,000 per year in the first couple of years, so $10,000 over two years replaces only 30 percent of the loss. Similarly, insurance benefits should be extended to workers earning more than $50,000 on their new job since this would exclude substantially affected middle-class employees and their families from insurance. Since most evidence suggest that earnings losses last at least three years, and likely many more, a proposal with sharp limits has to educate workers about the long path to recovery.