Weekend reading: Studying the Fed edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

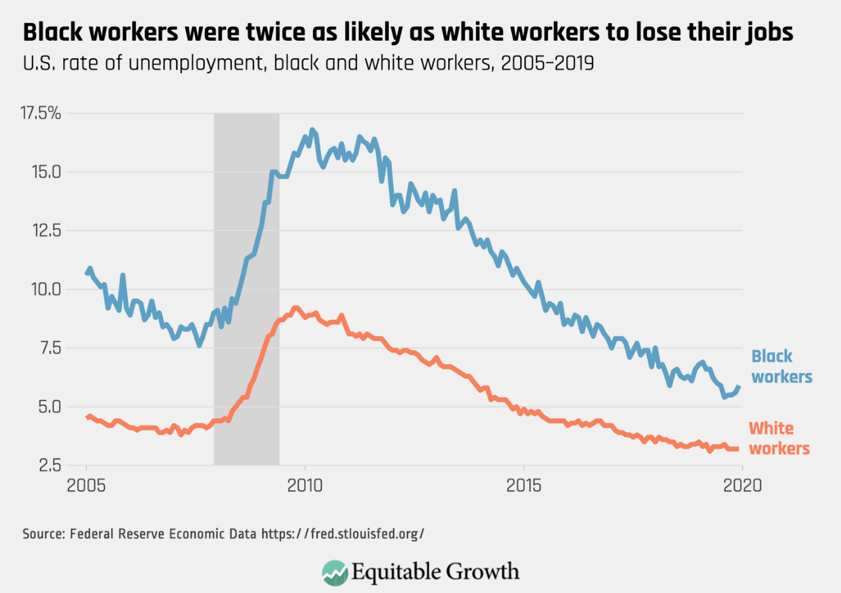

The most important economic decision taken this week may have been made not by Congress or the executive branch, but by the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee, argues our Director of Macroeconomic Policy Claudia Sahm in the debut of her new column. The connection between the Fed and its decisions and U.S. workers and their wages is stronger than you might think, she continues, describing the historical context surrounding the meeting this week, including the Fed’s actions during and after the Great Recession. Despite the Fed’s dual mandate to pursue both stable prices and maximum employment across the nation, almost every policy meeting of the Fed discusses inflation while its commitment to pursuing maximum employment for all groups of workers has been more halfhearted. Likewise, there have been few discussions about the unequal effects of policies on different racial groups. But, Sahm concludes, this may change in the future, as the Fed has begun reviewing its approach to monetary policy.

Why is the gender wage gap in the United States persisting despite many efforts to close it? While discrimination and differences in the places women tend to work can explain some of the difference, write Heather Boushey and Kate Bahn, research shows that women’s continued greater responsibility for family care also plays a role. In a reproduced column that originally appeared in 2019 in the Labor and Employment Relations Association journal LERA Perspectives on Work, Boushey and Bahn review the research on the role of care in the labor market and how other economic trends and structures, such as monopsony, affect the gender wage gap.

Earlier this week, legislators in Congress held hearings on various proposals to provide paid family and medical leave to U.S. workers, including the FAMILY Act, which, Alix Gould-Werth writes, is the most universal and ambitious of the pending plans. Equitable Growth released a fact sheet late last week covering evidence from the states that have existing paid leave proposals, as well as states that are currently implementing paid leave, to provide insight into what aspects are most important to allowing workers to balance their caregiving and labor market responsibilities.

Harvard University’s Labor and Worklife Program recently launched its “clean slate for worker power” agenda, which provides a series of policy recommendations surrounding the legal framework around organized labor in order to ensure all workers experience the gains of economic growth. Kate Bahn summarizes some of the policy proposals found in the agenda, including graduated representation, ways to address the exclusion of certain types of U.S. workers from representation, and support for workers to participate in our democracy, such as by voting. Bahn concludes that this new agenda “would shape the economic forces that determine individual and collective well-being so that the concerns of today’s economy, such as rising monopsony power and persistent racial inequality, are addressed through a rebalancing of power toward the workers who contribute to economic growth.”

Equitable Growth’s Director of Tax Policy Greg Leiserson wrote a chapter called “Taxing Wealth” in a new book published by The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project. He makes the case for reforming the taxation of wealth in the United States, detailing four specific approaches and the economic effects, the pros, and the cons of each one. You can read the abstract on our website, and find the full chapter over on the Brookings site.

In Brad DeLong’s Worthy Reads column, he recommends and provides analysis on some of the week’s most important content, both from Equitable Growth and around the web.

Links from around the web

The idea of “full employment,” one of the Federal Reserve’s mandates, has long been a politically charged term in the United States because economists don’t agree on how low exactly unemployment can fall without triggering inflation. Case in point: In 2019, the Fed was forced to lower interest-rate increases that it had put in place in 2018, in part because it had underestimated the number of jobless U.S. workers. But, writes Matthew Boesler for Bloomberg Businessweek, “Fed officials are currently engaged in some deep introspection about what they got wrong. At the center of those discussions is the notion of full employment.” Boesler goes through the political history of the term, which began around the Great Depression as something “more than just a single number estimated under scientific pretenses by central bank technocrats,” and has since evolved and been redefined under different economic schools of thought and presidential administrations.

A recent analysis at the Brookings Institution delved into the monthly jobs reports put out by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics to examine the positive trends—low unemployment rates, a decade of growth, higher wages—in more detail. The researchers, Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman, found a much less rosy picture than what we often read about: 53 million workers between the ages of 18 and 64 earn barely enough to live on, about $18,000 per year on average. They show that these statistics are not only describing young people just entering the labor market, or students working part-time, or otherwise financially secure workers, but actually that millions of hardworking adults “struggle to eke out a living and support their families on very low wages.” And, rather than just pushing for upskilling, more training, and higher education, Ross and Bateman argue that we need to take a closer look at the jobs our economy is providing, the wages those jobs are paying, and to whom specifically.

Why do we talk so much about providing families with choices when it comes to care responsibilities, asks Claire Cain Miller in The New York Times’ The Upshot blog, when many parents, and especially mothers, feel they actually have little choice in the matter when making decisions about work and family? The word “choice” ignores the structural barriers that are actually forcing these choices: The United States doesn’t provide universal paid family leave, free childcare, or public preschools to working families, and rising costs from healthcare to housing are overwhelming household budgets, while many women still experience earnings inequities after giving birth. Cain Miller dissects the idea of choice in the context of U.S. political history, particularly in the arena of family and gender policy, and how “the language of choice continues to shape policy debates.”

The United States is potentially facing yet another housing crisis: many Americans’ inability to afford housing, even at the lowest entry point of the housing market and regardless of the desire to rent or buy. This is likely because there simply isn’t enough housing to go around, writes Felix Salmon for Axios, and prices are rising too fast. A recent study shows that “entry-level houses are worth on average 50 percent more than they were at the beginning of 2012,” and certain metropolitan areas in the country have seen prices go up by as much as 89 percent since 2012. The cost of building housing has also gone up, meaning builders have less incentive to create new units. “Whether you rent or own ultimately matters much less than whether you have a place to live at all,” Salmon concludes.

Friday Figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Why Americans need to know more about the Federal Reserve” by Claudia Sahm.