Weekend reading: Reducing uncertainty in tax refunds to reinforce their value edition

This is a post we publish each Friday with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth published this week and the second is relevant and interesting articles we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

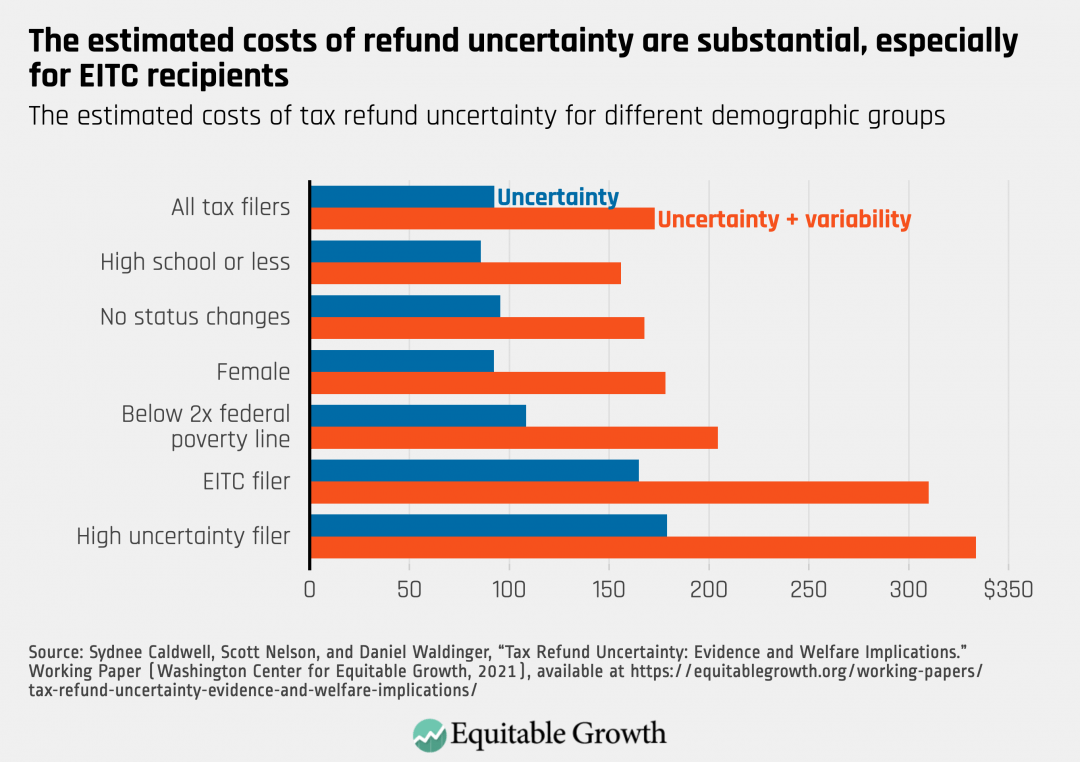

As U.S. workers file their tax returns for 2020, new research shows that uncertainty about the amount individual filers may receive in their tax refunds hinders the effectiveness of tax-based redistribution from two refundable tax credits. The Earned Income Tax Credit and the Child Tax Credit comprise a significant portion of income for their respective 25 million and 48 million recipients, but the rules governing access and eligibility for the credits are complex and leave many individuals without an accurate estimate of the size of their refunds. This affects low-income workers in particular, write Sydnee Caldwell, Scott Nelson, and Daniel Waldinger, as well as those with dependents, those who experience large yearly changes in their incomes, and young filers. The co-authors summarize their recent working paper, which finds this uncertainty limits the ability of recipients to plan their finances throughout the year, reducing the value of these important tax credits. In fact, the co-authors find that average recipients would be willing to forgo roughly 10 percent of the total value of the credit they receive to eliminate uncertainty about the refund amount. Policymakers can use these findings as they design and implement stimulus efforts and strive to make tax policy work for filers along the income distribution.

This week, a group of more than 200 economists—including many in Equitable Growth’s network and led by Hilary Hoynes, professor of public policy and economics at the University of California, Berkeley; Trevon Logan, professor of economics at The Ohio State University; Atif Mian, professor of economics, public policy, and finance at Princeton University; and William Spriggs, professor of economics at Howard University—sent a letter to congressional leadership urging them to invest in both physical and care infrastructure, as well as science and technology, as part of President Joe Biden’s infrastructure and jobs plan. The signees argue that the private sector alone cannot address the various structural challenges facing the United States, from climate change to systemic racism to a crumbling care economy. And, they write, the share of U.S. Gross Domestic Product invested in federally funded research and development has declined to just 0.6 percent, resulting in less knowledge creation, fewer good jobs, and added difficulty in boosting employment in new sectors. If passed, these public investments could spur strong, stable, and broadly shared economic growth—and policymakers can take advantage of the current low-interest-rate environment to reassert the United States’ global leadership position and solve the problems of the 21st century.

This week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released data on hiring, firing, and other labor market flows from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, better known as JOLTS, for February 2021. Kate Bahn and Carmen Sanchez Cumming put together five graphics highlighting the main trends in the data.

In Brad DeLong’s latest Worthy Reads column, he summarizes and provides his take on recent content from Equitable Growth and across the internet.

Links from around the web

President Joe Biden recently released his plan to shore up the economy and bolster U.S. infrastructure. The $2 trillion plan will be paid for via higher taxes on corporations over 15 years and includes several proposals and areas for improving both physical and care infrastructure. Alicia Parlapiano and Jim Tankersley break down what’s in the legislative proposal in The New York Times’ The Upshot blog. They detail the main areas of the package—transportation, buildings and utilities, jobs and innovation, and in-home care—the cost of each proposal within the areas, and what they hope to achieve. It’s an easy-to-grasp summary of how President Biden hopes to accomplish some of his main goals: revitalizing the nation’s crumbling and outdated buildings, roads, and bridges; reducing U.S. dependence on fossil fuels; and improving jobs in the innovation, tech, and care sectors.

In an in-depth feature, Vox’s Emily Stewart interviews workers across the United States living on the minimum wage, documenting their challenges trying to eke out a living. The federal minimum wage has been set at $7.25 per hour since 2009—at 40 hours per week, this adds up to $15,000 annually—a rate that is not enough to cover basic expenses in any state, particularly for those with dependents. Millions of U.S. workers make that or even less, and many rely on the social safety net and other public assistance to supplement their income in order to get by. Though many of the workers who Stewart interviews expressed some concerns about the implications of a minimum wage hike, including job losses or increased automation, most also lamented the difficulty that they experience with their current salaries in paying their bills or saving, not to mention affording a vacation or covering an emergency expense. Stewart writes that these workers aren’t necessarily looking to live a life of luxury. Rather, they want to be able to afford everyday expenses such as food, health insurance, and rent. In other words, they just want to be able to live. The inability to earn a living, let alone save money, prevents many workers from achieving important wealth- and income-building milestones, such as buying a home or going to college, holding back the overall economy and contributing to widening inequality in the United States.

LinkedIn will soon allow workers to describe their employment status as “stay-at-home parent.” The Lily’s Soo Youn says this may help normalize caregiving as an occupation. Particularly amid and in the aftermath of the coronavirus recession—as 2.5 million women left the labor force, often citing caregiving needs as the reason—this is a welcome change. Though women are slowly starting to close the gender gap in unemployment during this recession, they also often have a harder time returning to work after leaving the labor force than men—though all workers experience penalties for taking time to care for their families. LinkedIn’s new feature aims to reduce this discrimination and stigma, Youn writes, hopefully ensuring those who take time off either voluntarily or otherwise don’t have to settle for lower pay or lesser roles when trying to reenter the job market.

Friday figure

Figure is from Equitable Growth’s “Uncertainty about the size of annual tax refunds hinders the effectiveness of tax-based U.S. redistribution,” by Sydnee Caldwell, Scott Nelson, and Daniel Waldinger.