The long-term consequences of recessions for U.S. workers

Policymakers have asked—in some cases, demanded—that people stay home and businesses shutter as a public health crisis has unfolded across the United States, inducing an economic downturn. Despite positive developments in legislation passed last week, those policymakers have not put in place all the steps needed to protect workers and businesses from a full-scale recession that may cast a shadow for years to come. Given the likely scope and scale of this crisis and the current public policy response—which, from both a public health and economic perspective, has been insufficient—it is looking increasingly likely that the United States may be on the cusp of a severe economic recession.

What does the evidence from the Great Recession of 2007–2009 say about what an extended recession could mean for working people over the long term, especially young workers?

There is extensive research on the effects that economic downturns have on workers’ employment and earnings, not just during a recession but also lingering for years and decades afterward. In a new working paper, University of California, Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein finds that workers who happen to be entering the labor market when there’s a recession have both permanently lower employment rates and lower earnings long after the recession has ended. These effects for recent entrants are even worse than for other members of the U.S. labor force who have been in it longer, as Rothstein explains in a column about the paper:

Workers from these cohorts saw their annual employment rates drop by 2 percentage points to 4 percentage points per year, relative to older workers in the same labor market. Those who were established in the workforce by the beginning of the recession—those who graduated college in 2005 and earlier—essentially returned to prerecession levels of employment by 2014. But those who entered after 2005 have not; their employment rates remain depressed even as the overall market has recovered.

Unfortunately, these effects are not temporary. Rothstein estimates that the permanent effects, or scarring, of the Great Recession on young workers will result in those individuals earning 2 percent less through the early years of their careers and will reduce their employment throughout the course of their career by about one week. While these amounts might sound small for one individual, aggregated across an entire generation, they represent a large loss of earnings and employment.

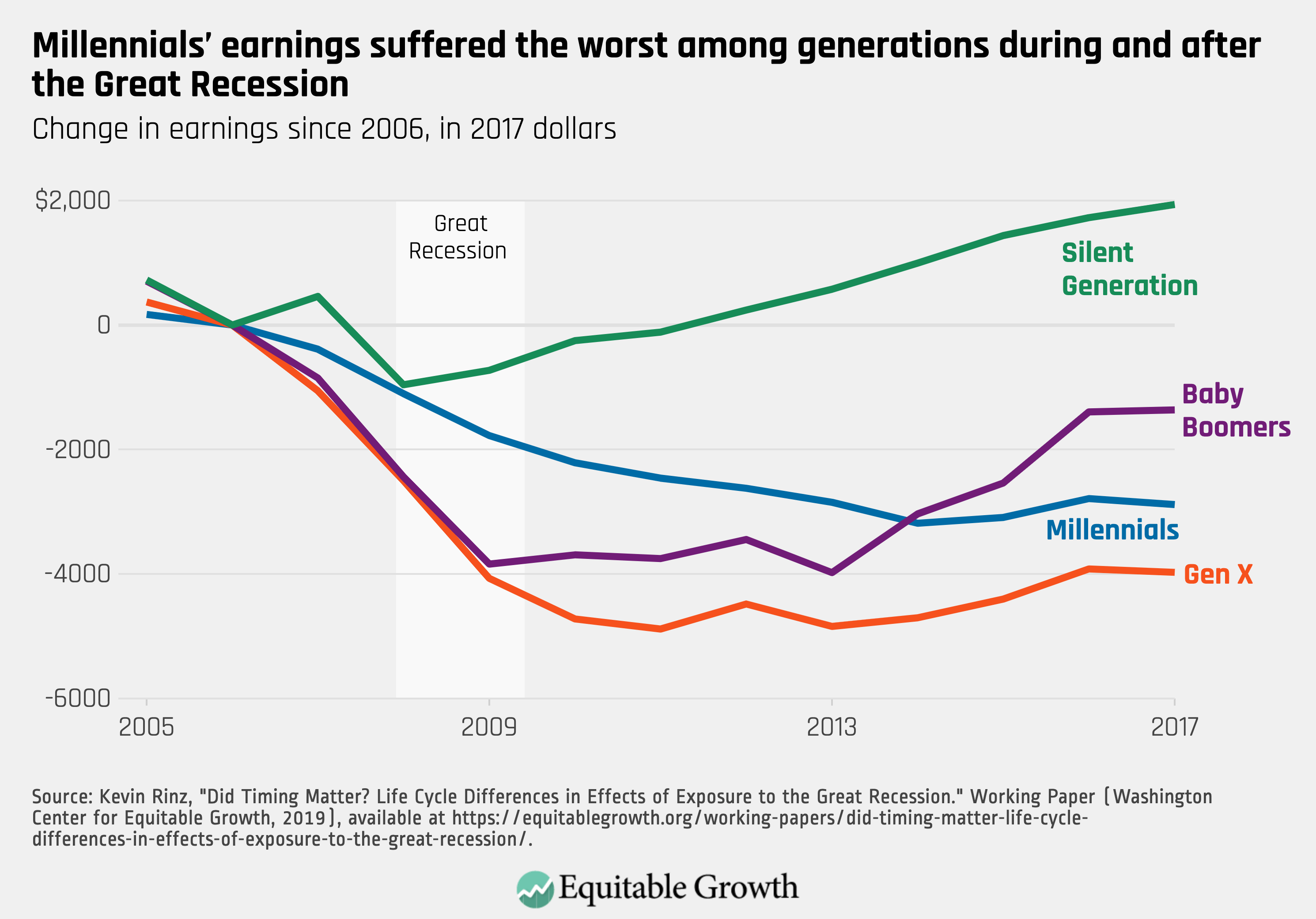

Another new working paper that explores the negative effects the Great Recession had on young workers in particular is by U.S. Census Bureau economist Kevin Rinz. He finds that from 2007 to 2017, millennials whose local labor markets had higher unemployment lost 13 percent in cumulative earnings, compared to 9 percent for Generation X and 7 percent for the baby-boom generation. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

These worse earnings outcomes relative to older workers persisted even as these millennials were more likely to be employed again by 2017. Rinz then discusses a few different reasons why younger workers’ earnings would still be depressed even as their employment improves.

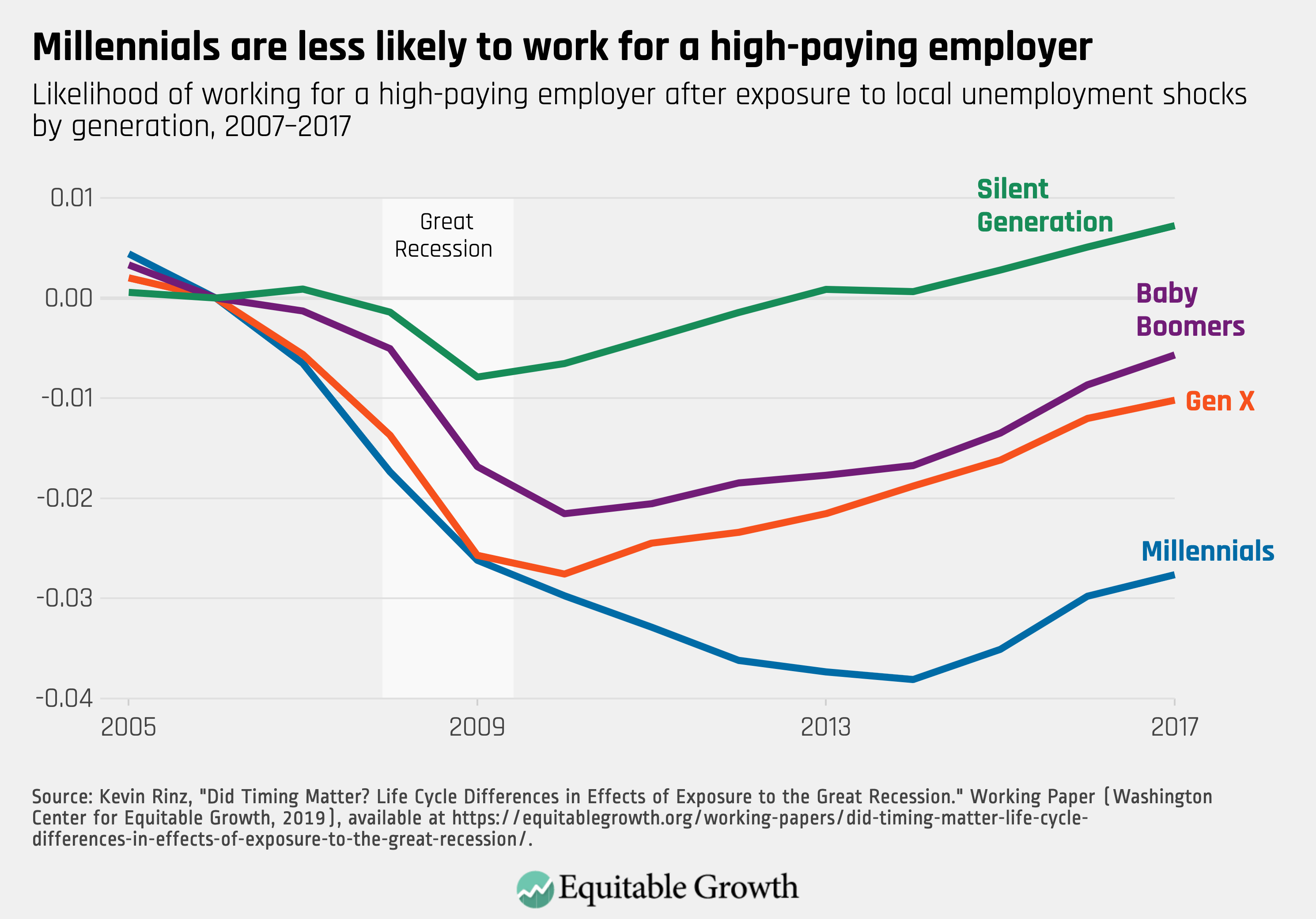

One of those ways is that younger workers, especially millennials, were still less likely to be working for high-paying employers even as their employment recovered. Meanwhile, older workers saw their chances of working for high-paying employers improve roughly proportionately to their likelihood of being employed. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

You can read more about Rinz’s paper in this column by Equitable Growth Director of Labor Market Policy Kate Bahn.

One of the reasons it’s so concerning to see that recessions have such negative consequences for young workers is because where you start out in the earnings distribution has important implications for your long-term earnings trajectory—even if you don’t have the bad luck to be entering the labor market during a recession. Research funded by Equitable Growth by Syracuse University economist Emily Wiemers and University of Massachusetts Boston economist Michael Carr found that people are less likely to move up the earnings distribution over the course of their career than they used to. They find that the likelihood of a worker who starts their career in the middle of the earnings distribution moving to the top decile of the earnings distribution has declined approximately 20 percent over the past 40 years.

This means people are more “stuck in place” in the earnings distribution throughout the course of their careers, with less chance of earning more as they grow older and more experienced. This also means that where one starts on the earnings ladder is more indicative of where you will finish in the earnings ladder than used to be true. This is true even for college-educated workers, who may have higher earnings overall but have actually seen their lifetime earnings mobility decline the most.

The combination of these cyclical factors caused by recessions and structural factors driven by long-term changes in earnings mobility have profound implications for the long-term economic opportunity that young workers face. As my co-author Elisabeth Jacobs and I explain in our report, “Are today’s inequalities limiting tomorrow’s opportunities?,” these changes together represent one way in which even highly skilled and highly “human capitalized” workers face lower prospects of economic mobility relative to prior generations.

This means that while much of our political and policy rhetoric continues to emphasize the role of individual skills, education, and hard work to explain economic outcomes, the reality is that far too often, economic outcomes reflect factors beyond an individual’s control, from racial and gender discrimination to the dumb luck of happening to be a young adult entering the labor market during a recession.

Research from the Great Recession indicates that the 2007–2009 downturn had deep and long-lasting negative economic impacts on people. The current downturn caused by our coronavirus-driven economic shutdown has already had dire impacts on workers, seen last week in the unprecedented jump in Unemployment Insurance claim filings. But as we have seen from the research above, recessions’ negative economic effects also linger for years afterward in depressed earnings and employment, and this current downturn may linger even longer due to underlying fragilities in the U.S. economy caused by historically high economic inequality and a porous social safety net.

That’s why it’s crucial that policymakers take swift and decisive action to ensure not only that income keeps flowing in the short term but also that permanent, inequality-fighting policy changes are enacted to improve the country’s safety net and enhance automatic fiscal stabilizers in the long term. The legislation enacted last week is a good down payment on that goal, but further interventions may be needed as our economy continues to suffer from the consequences of the coronavirus.