The hidden trade-offs of nonwage job amenities for U.S. workers

When workers choose jobs with predictable schedules, safer conditions, or greater autonomy, they are often paying a price: lower wages. In some cases, these hidden trade-offs are considerable. Indeed, my research shows that these “amenity trade-offs” can account for as much as two-thirds of the gender pay gap.

In this column, I first introduce a new approach built upon my research to measuring these nonwage amenities trade-offs and then explain what the findings mean for both economists and policymakers seeking to understand and address persistent income inequality. I close with suggestions for how to foster a more equitable U.S. labor market that reframes how our nation values work, wages, and amenities.

A new approach to measuring job amenities

Economists have long recognized that workers care about more than wages. Surveys consistently show that people value features such as better scheduling options, safety, autonomy, and meaningful work. Yet preferences don’t always translate into prices.

Suppose men prefer coffee in the break room, for example, while women are more likely to want tea. As long as both options are equally costly for employers to provide, even large differences in preferences won’t contribute to the gender pay gap. Though simple, this example illustrates the importance of a broader question: When workers choose jobs with certain amenities, how much do they have to sacrifice in foregone wages?

Prior research has struggled to capture how much workers must trade off when choosing between wages and amenities. Traditional approaches often rely on wage comparisons across workers with different amenities but the same observable characteristics, such as education or experience, to estimate how much certain job features are worth to workers. But these methods assume that once economists control for observable factors, workers have roughly equal access to all jobs.

In reality, the U.S. labor market is segmented such that some jobs are better than others, and factors that are not easily observable such as search frictions or difficult-to-measure skills also influence which job options workers have.

Another common strategy compares workers’ own job changes over time, but this too can be misleading. Workers who move to higher-paying jobs typically also gain better amenities, such as safer conditions, suggesting that simple within-worker comparisons confound amenity choices with career advancement.

To address this gap, I developed a new estimation strategy—what my colleagues have since dubbed the anti-instrument method—that treats observed productivity factors, such as education, not as perfect controls but as shifters of the set of offers available to workers. This method recognizes the vertical segmentation of the labor market, where access to better jobs depends not only on observable characteristics but also on unobserved or structural factors.

By using information on how these observable traits on average increase access to better job options rather than fully explain job choice, this estimator captures the real trade-offs workers face between pay and amenities. This approach reveals clear and consistent estimates of amenity costs, overcoming the biases that have plagued standard methods.

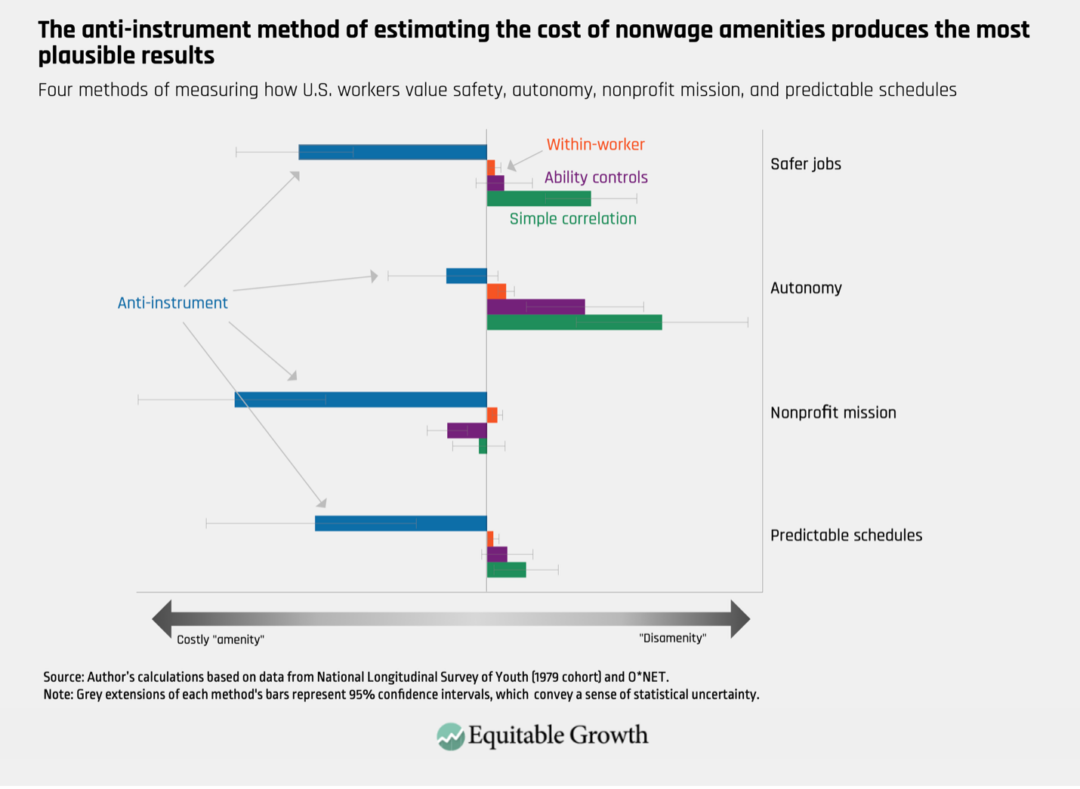

Figure 1 below illustrates how four different estimation approaches compare in practice: simple correlations, the strategy of controlling for observed abilities, the within-worker method, and my anti-instrument approach. We can easily see that using raw correlations or simple controls often leads to implausible conclusions—for example, that safer jobs pay more. Yet this finding contradicts basic economic reasoning that a trade-off should exist between safety and pay.

Even after including controls for observed ability measures, for example, within-worker comparisons can misleadingly suggest that higher-paying jobs come with better amenities. In contrast, the anti-instrument method reveals a more intuitive pattern: Workers must often give up pay to obtain safer conditions, more decision-making autonomy, more meaningful work in nonprofits, and more regular schedules. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

These results are striking. They overturn longstanding assumptions about the ability of researchers to detect this hidden structure of job choice. They show that standard approaches overlook the way workers are sorted into different levels of the U.S. labor market, where some jobs come with better pay and amenities and others do not. This hidden hierarchy plays a powerful role in shaping workers’ opportunities and compensation—and as a result also shape income inequality and the gender wage gap. These types of findings using the anti-instrument approach are being echoed by work in many fields, including labor, management, environmental, urban, and macroeconomics.

Amenity trade-offs and the gender pay gap

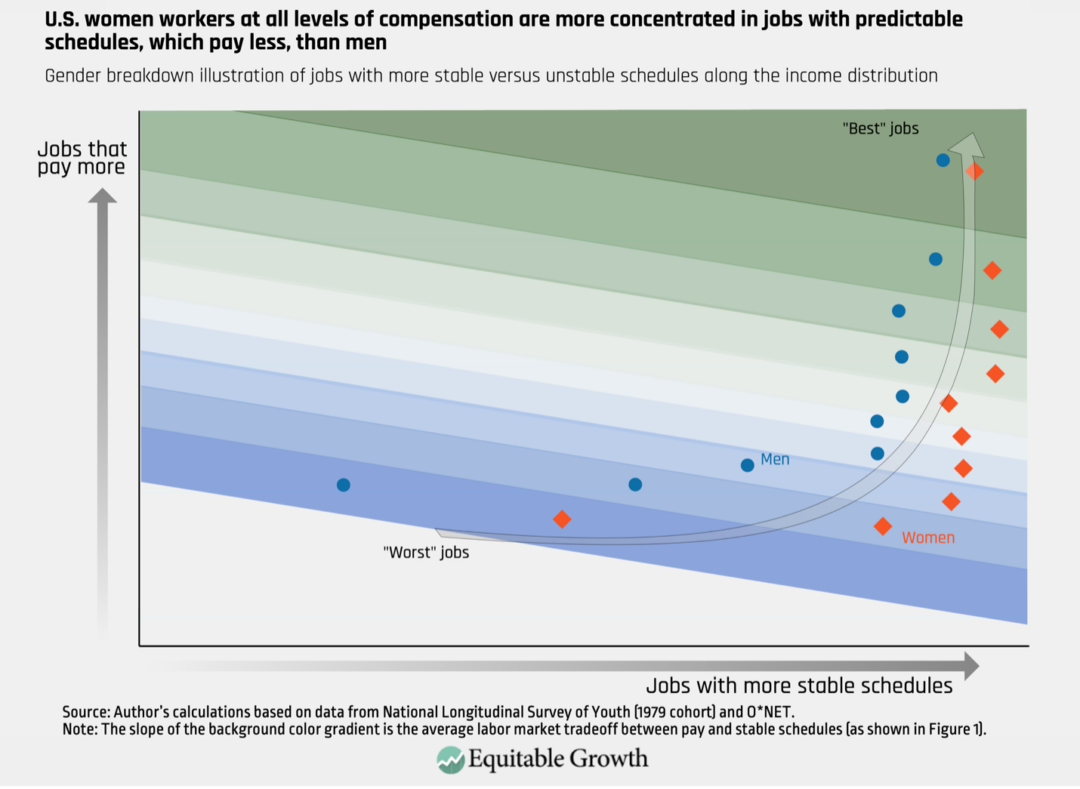

These findings reframe how researchers think about income inequality and, in particular, the gender pay gap. Figure 2 below illustrates how these patterns relate specifically to gender and stable schedules. At nearly every level of compensation, women are more concentrated in roles with regular schedules, while men are more likely to hold jobs in which the schedule changes with demands of the employer or customer. The data also show that the U.S. labor market requires workers to sacrifice some pay to obtain a job with a more predictable schedule. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

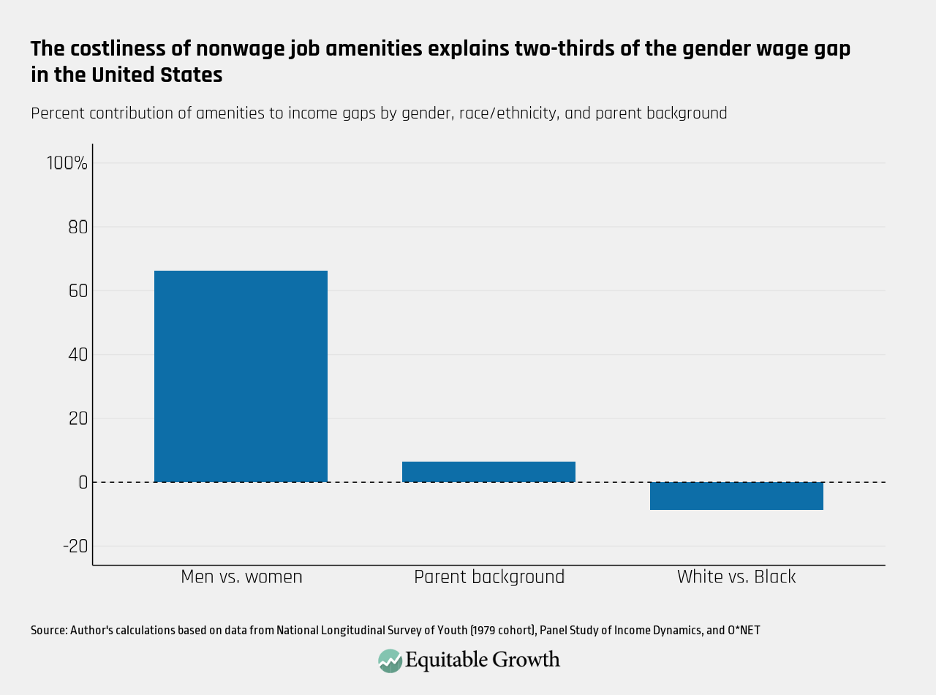

Taking into account a wide range of amenities, I find that the costliness of amenities explains a substantial portion of the gender pay gap—up to two-thirds. Yet my findings look different for racial and socioeconomic inequality.

For workers from lower-income backgrounds or Black workers, for example, pay gaps are less about amenity choices and more about access to high-paying jobs in the first place. In these cases, the data show that workers from marginalized groups often face structural barriers to entering better-compensated roles, regardless of the amenities those roles offer.

When I decompose the pay gap by parental background, however, a small but consistent pattern suggests that intergenerational preferences for work characteristics—such as working in a job that conveys a sense of meaning—may contribute to persistent income gradients. This hints at a mechanism where preferences for certain job features passed down through families may help perpetuate class-based inequality, though the effect is quantitatively much smaller than for gender. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

This pattern points to a broader issue in how researchers and policymakers alike approach the gender pay gap today. It is more than a matter of women being paid less than men for doing the same work. Rather, the gap increasingly reflects the fact that women are often boxed out of higher-paying roles because those jobs come with different nonwage attributes, such as unpredictable schedules or long hours.

In many cases, the U.S. labor market presents a steep earnings trade-off to access a job with amenities such as predictable schedules, autonomy, and workplace safety. Given the constraints that society also often imposes on women, such as those related to child care or caring for an elderly family member, what deserves more attention is whether workers—and especially women workers—should have to make this kind of trade-off at all.

Moving toward a more equitable U.S. labor market

These findings carry significant implications for both research and policy. A “good” job today is defined by more than just wages—it is also about myriad other factors, such as meaning, predictability, and autonomy. Yet the way the U.S. labor market prices these features often penalizes workers for seeking them. Importantly, these penalties aren’t simply reflections of individual choices but additionally are shaped by structural constraints, including limited access to higher-paying jobs and societal expectations around caregiving and other gender norms.

For policymakers, this means that raising wages alone is unlikely to close the gender wage gap. Instead, policymakers need to rethink how different job attributes are valued and how regulations and standards can reshape the trade-offs workers face. Workplace safety regulations have already shown that public policy can influence amenity trade-offs through standards and enforcement by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Many studies also are exploring how increasing the provision of a wide array of amenities—including predictable schedules and work-from-home arrangements—can potentially reduce the gender pay gap. Expanding protections against unstable schedules or ensuring compensation for predictable hours also could help narrow gender gaps.

At the same time, tackling racial and class-based pay gaps requires a different approach. These gaps are primarily driven by barriers to entry into highly compensated roles. Policy efforts to address these disparities should focus on expanding access to education and training for underrepresented groups, addressing systemic biases in hiring and promotion, and reducing structural obstacles that limit access to lucrative career paths.

My research introduces a new approach—the anti-instrument method—to uncovering the trade-offs workers face between pay and job attributes, such as safety, predictable schedules, and meaningful work. By identifying how these trade-offs shape who holds which jobs and at what cost, the findings reveal a U.S. labor market where essential job features come with a hidden price.

This hidden cost disproportionately affects women and is a major contributor to income inequality by gender. The talents of many workers, including many women who are boxed out of roles where they could contribute the most, will continue to be squandered because of these hidden trade-offs that create barriers to advancement. Policymakers and other stakeholders should act swiftly to rethink and revise the rules of the U.S. labor market and reverse these trends.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!

Stay updated on our latest research