Overview

Decades-old conventional wisdom held that businesses organized as partnerships in the United States were mostly small enterprises with a handful of active individuals sharing personal liability for the businesses they own—largely retail shops, law firms, and doctors’ offices. Indeed, the tax rules governing partnerships, which haven’t changed much since they were created in the 1950s, were designed with this type of relatively simple business arrangement in mind, offering tax advantages to help these small businesses thrive.

Yet today’s partnerships—at least the ones growing at the fastest clip—barely resemble those of the mid-20th century. Instead, massive, complex firms, particularly in the real estate and financial sectors, have come to dominate the partnership tax category, taking advantage of outdated rules to avoid billions of dollars in taxes.1 Meanwhile, truly small, simple firms—which still exist in large numbers within the partnership tax category but pale in comparison to the more complex firms in terms of income and assets—are not stretching the rules in the same way.

The number of U.S. firms opting to be treated as partnerships for tax purposes—one of the most popular types of so-called pass-through businesses—has grown considerably in recent years.2 Yet how these firms are structured and the ways in which they take advantage of flexible tax rules and lax enforcement has largely been a mystery.

New cutting-edge scholarship that uses administrative tax records sheds light on these questions, digging into the shadowy operations of partnerships with major implications for tax administrators, regulators, and legislators. Federal policymakers, particularly those looking to raise revenue to reduce the deficit or pay for other public priorities in 2025 and beyond, should view this as an area ripe for reform.

This report first looks at the findings from recent research on complex partnerships and tax avoidance that describes who owns these firms, what types of firms are most likely to be complex, and how these firms use flexible tax rules to reduce their tax rates. It then turns to possible policy responses, including more stringent rules, targeted enforcement, and improved reporting, before offering concluding thoughts.

Recent research on complex partnerships and tax avoidance

Economic researchers recently have been attempting to better understand large, complex partnerships—a tax category that includes limited liability companies, limited partnerships, limited liability partnerships, and general partnerships.3

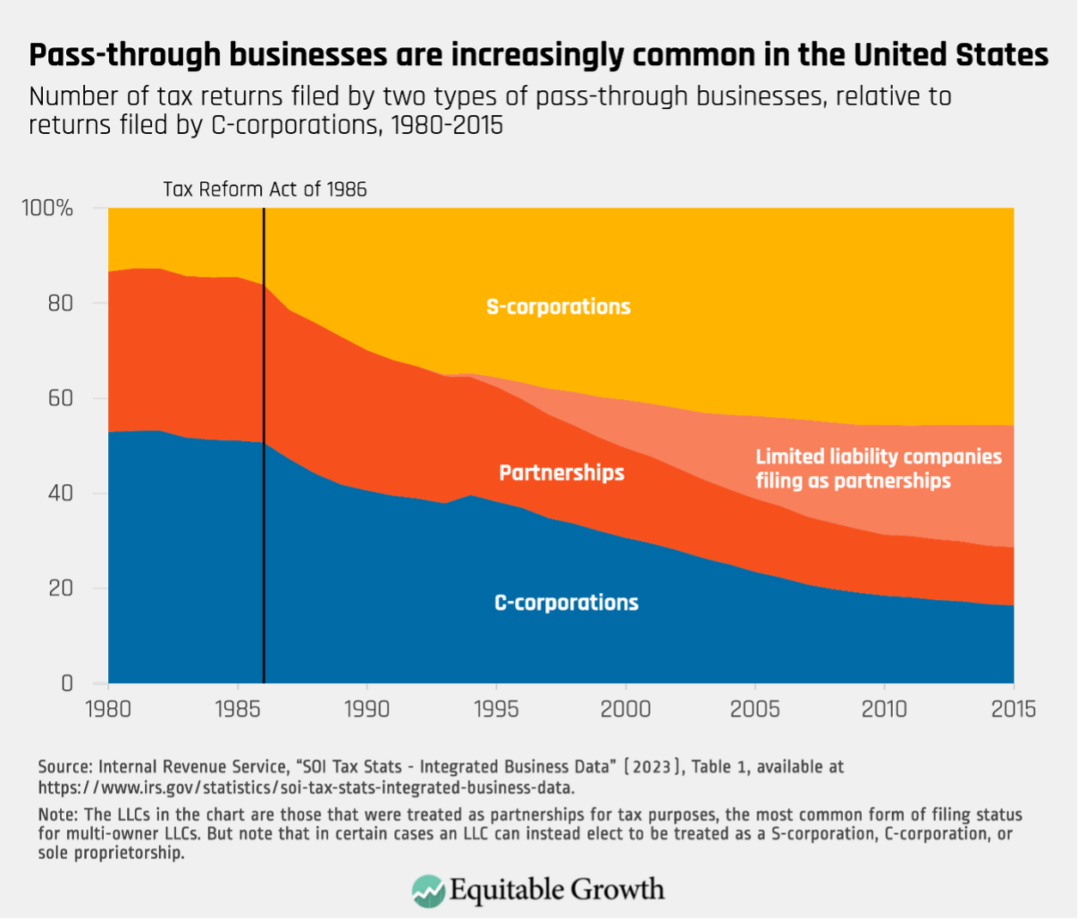

In 2015, for example, two tax policy experts—Jason DeBacker, then at Middle Tennessee State University and now at the University of South Carolina, and Richard Prisinzano, formerly at the Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis and now at The Yale Budget Lab—identified the growing use of partnerships, especially limited liability companies, for tax purposes. LLCs are a type of state-law-created organizational form that protects all owners’ personal assets from creditors. They became popular in the 1990s,4 driven by a number of factors, including lower tax rates from the 1986 Tax Reform Act and “check-the-box” regulations in 1996 that made it easy for LLCs and other business types to elect pass-through tax treatment. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Unlike C corporations, pass-throughs pay taxes on their owners’ personal tax returns rather than at the entity level. Aside from partnerships, the other main pass-through types are S corporations and sole proprietorships, though both of these organizational forms have strict rules on the number and type of owners, as well as how the businesses’ tax attributes are passed down to owners. Partnerships, on the other hand, are allowed to have an unlimited number of owners, which can be trusts, C corporations, S corporations, individuals, or even other partnerships, and can flexibly allocate tax benefits to owners.

The resulting partnership structures can be very complicated. In 2016, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Michael Cooper and his co-authors from the U.S. Treasury Department, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Chicago linked partnership tax data with their owners’ tax information. They found that partnership income is relatively lightly taxed, facing an estimated effective federal tax rate of 15.9 percent in 2011, compared to 24.9 percent for S corporations and 31.6 percent for C corporations that year.5 They also found that this income accrues overwhelmingly to high-income individuals: In 2011, the average household in the top 1 percent of the income distribution earned more than 600 times the amount of partnership income as the average household in the bottom half of the income spectrum.

Even with this low effective tax rate, it has long been suspected that pass-throughs—and partnerships in particular—are not living up to their full tax obligations, probably for two main reasons. First, they are not subject to third-party information reporting.6 Instead, partners effectively self-report their financial activities each year, offering an opportunity for obfuscation, if not abuse.

Second, there are large incentives for partners to mischaracterize income or their roles in the enterprise to take advantage of various tax loopholes, such as the limited partner exception, a controversial tax maneuver that allows a partner involved in the day-to-day management of a firm to avoid the self-employment tax.7 Indeed, there is suggestive evidence that a large portion of overall pass-through income is labor income that has been disguised as ordinary operating income to avoid payroll and social insurance taxes.8

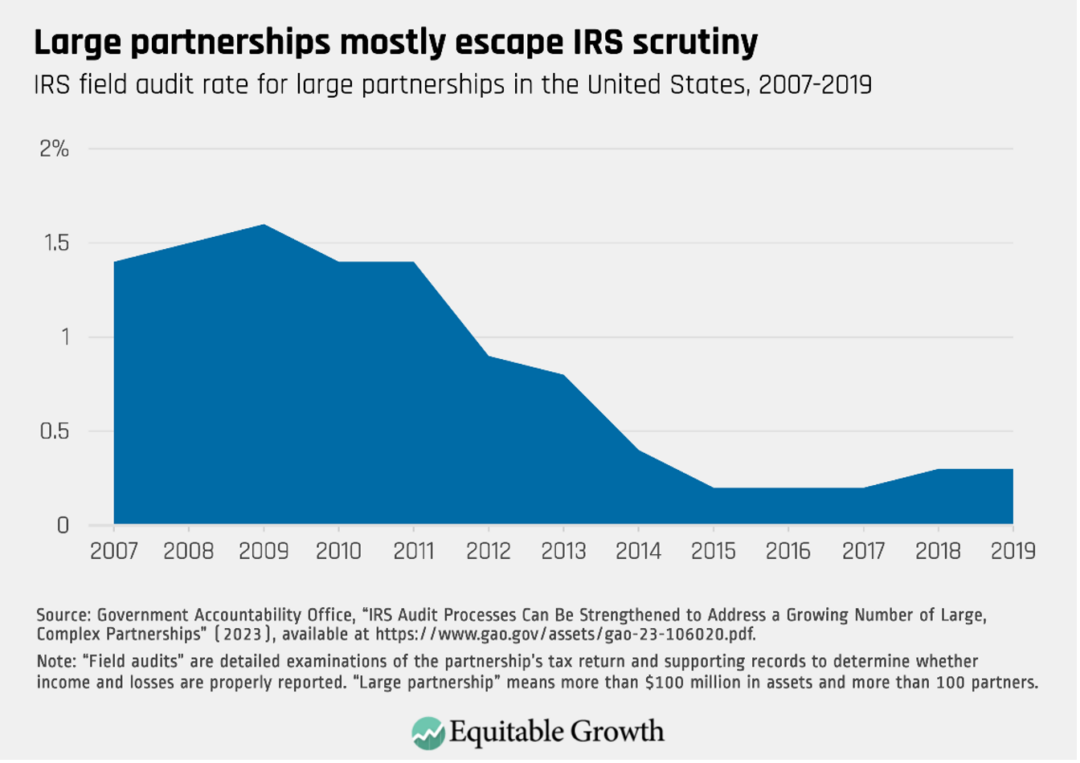

Other research from the past decade adds to these findings. In 2014, for instance, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found not only that partnerships were becoming larger and more popular, but also that the IRS was not keeping up with auditing these firms‚ meaning much of this potential tax evasion is going unscrutinized.9 Indeed, the GAO report found that it proved almost impossible for the IRS to conduct thorough audits because of its reduced resources and partnerships’ opaque ownership structures. The U.S. Government Accountability Office has recently updated and corroborated these findings.10

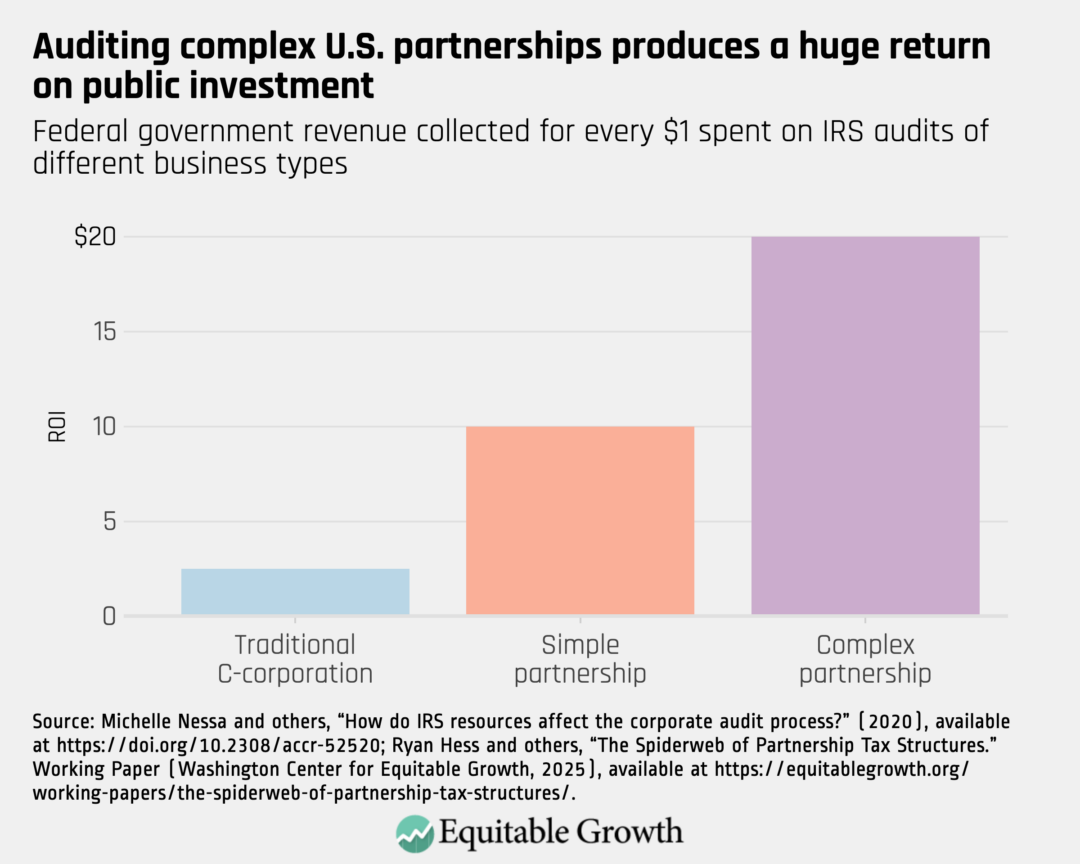

Additionally, two new papers bring these phenomena into even sharper focus. One of these papers, published today in Equitable Growth’s Working Paper series,11 uses confidential, anonymized IRS administrative records, as well as cutting-edge computer science techniques, to identify what they call a “spiderweb” of partnership tax structures, highlighting the complexity of partnerships in the United States. Ryan Hess of the University of Georgia and his co-authors from New York University, Stanford University, University of Chicago, and the IRS argue that if the IRS audited these partnerships more aggressively, it could return $20 to the government for every $1 spent on enforcement—roughly double the return from auditing simple partnerships and eight times the return from auditing traditional C corporations.

The other new paper, by Michael Love of Columbia University, uses anonymized federal tax records to investigate how the largest, most complex partnerships take advantage of flexible tax rules that allow broad discretion in how to allocate profits and losses among partners.12 These rules allow partnerships seeking to lower their overall tax rate to allocate gains (particularly nonpreferred ordinary income, which is usually subject to higher tax rates) to partners in lower marginal tax brackets while allocating certain losses, deductions, or credits to partners in higher marginal tax brackets, for whom those tax benefits are most lucrative.

According to Love, this flexibility contributed to $331 billion in tax savings during the 10-year span from 2011 to 2020. While this represents only 1 percent of federal revenue over that period,13 it is nearly the cost of a universal pre-Kindergarten program in the United States.14 Though not technically a measure of lost revenue, this finding indicates that the federal government is likely losing billions of dollars each year to legal tax avoidance by wealthy owners of hedge funds, venture capital companies, and private equity firms—with highly questionable benefits to the public.

Combined, these two new papers make the following main points:

- Even though the majority of U.S. partnerships are simple and small in terms of total income and number of partners, those that are not tend to be massive, unwieldy networks of interconnected partners and firms. These complicated business structures are concentrated in the real estate and finance industries, represent the lion’s share of partnership income and assets, and are popular among high-income individuals.

- The largest, most complex partnerships employ the most aggressive tax avoidance strategies, which often involve flexible allocations of profits and loss, carried interest, and blocker corporations in tax havens.

- More stringent rules and more targeted enforcement in this area would likely raise considerable revenue for the federal government without affecting truly small firms or stifling economic dynamism.

Let’s now go through each of these points in turn.

Highly complex partnerships are concentrated in real estate and finance

According to the paper by the University of Georgia’s Hess and his co-authors, 80 percent of partnerships in the United States are relatively simple, owned only by individuals, and 70 percent of those simple partnerships are made up of just two people.15 Similarly, Columbia’s Love finds that roughly 75 percent of U.S. partnerships—or 3 million out of 4.1 million—are standalone entities and are not connected to any other partnership. (This slightly lower percentage is explained in part by Love’s dataset, which includes more multitiered financial firms.) These simpler arrangements are the relatively small enterprises that partnership tax law was originally designed to accommodate.

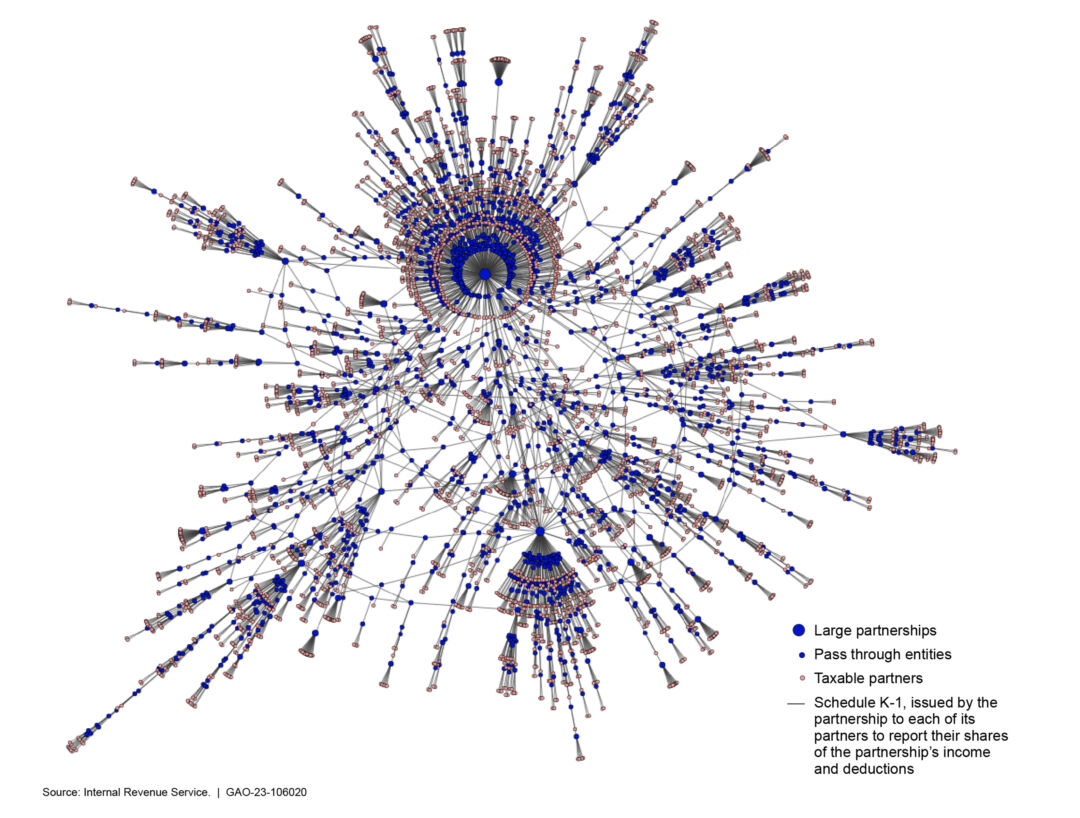

Yet, according to Hess and his co-authors, the remaining 20 percent of U.S. partnerships are part of complex organizations, featuring nonindividual owners and multiple tiers of ownership. They find that the average complex partnership has two ownerships tiers and is owned by 3.7 individuals, 1.7 partnerships, 0.2 C corporations, 0.4 S corporations, and 0.4 trusts. (See Figure 2 for an example of an especially complex partnership web.)

Figure 2

Large, complex partnerships involve a multitiered spiderweb of owners, including other partnerships

Illustrative example of a complex ownership structure for a large partnership in the United States

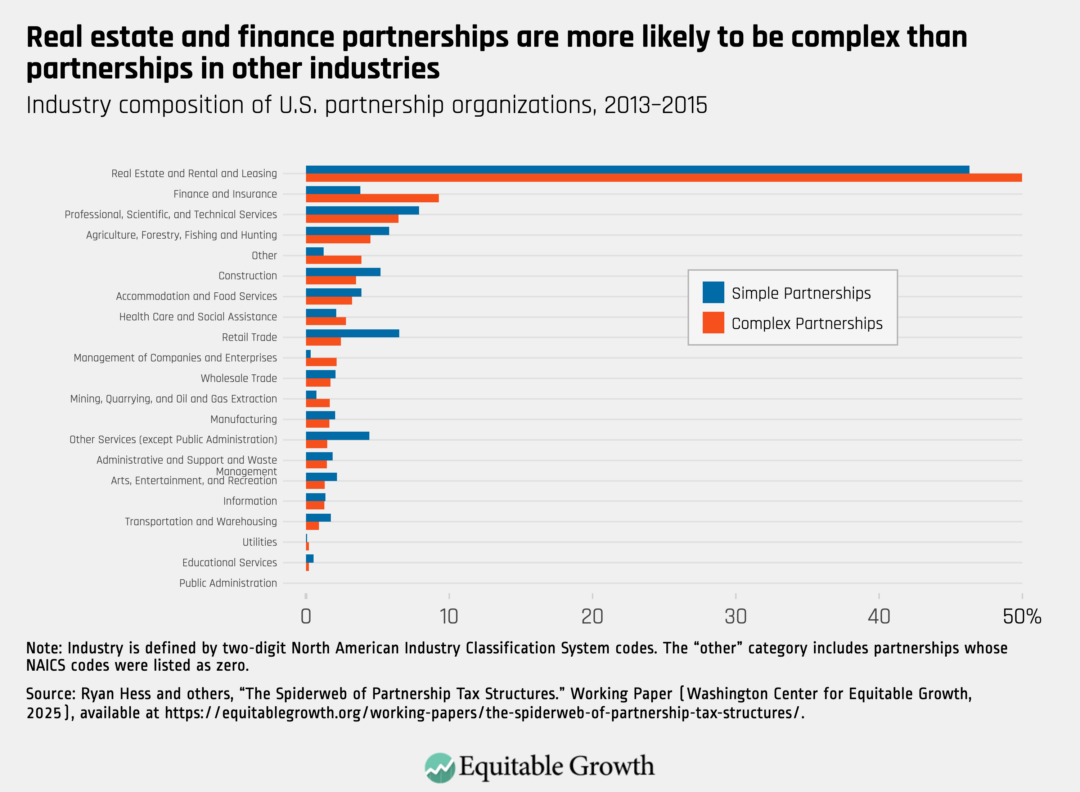

The study from Hess and colleagues finds that these complex partnerships are more likely to be in the real estate or finance and insurance industries16 and, compared to simple partnerships, are more likely to have a larger amount of assets (three times as many), higher sales numbers (twice as high), and more investment-related income (seven times more). (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Meanwhile, according to Columbia’s Love, roughly 16 percent of U.S. partnerships are interconnected in one gigantic “mega network” that represents roughly 60 percent of all partnership income and losses in the United States. This does not mean that these partnerships should be considered one business enterprise. Rather, it means there is at least some partial overlap in ownership, probably the result of a so-called daisy chain of partnerships in which, say, an investor in partnership A is also a small investor in partnership B, which itself is owned in part by an investor in partnership C.

Further, Love finds that 70 percent of this partnership mega network’s income and loss is represented by finance firms, and 60 percent of its income is reported as capital gains, dividends, or interest (sometimes called “portfolio income”). These findings are a sign that investments are these firms’ primary concern.

Complex partnerships use aggressive tax avoidance strategies

The new research on partnerships highlights two common tax avoidance strategies that U.S. partnerships use: flexible allocations of profits and loss, which includes carried interest, and blocker corporations in tax havens.

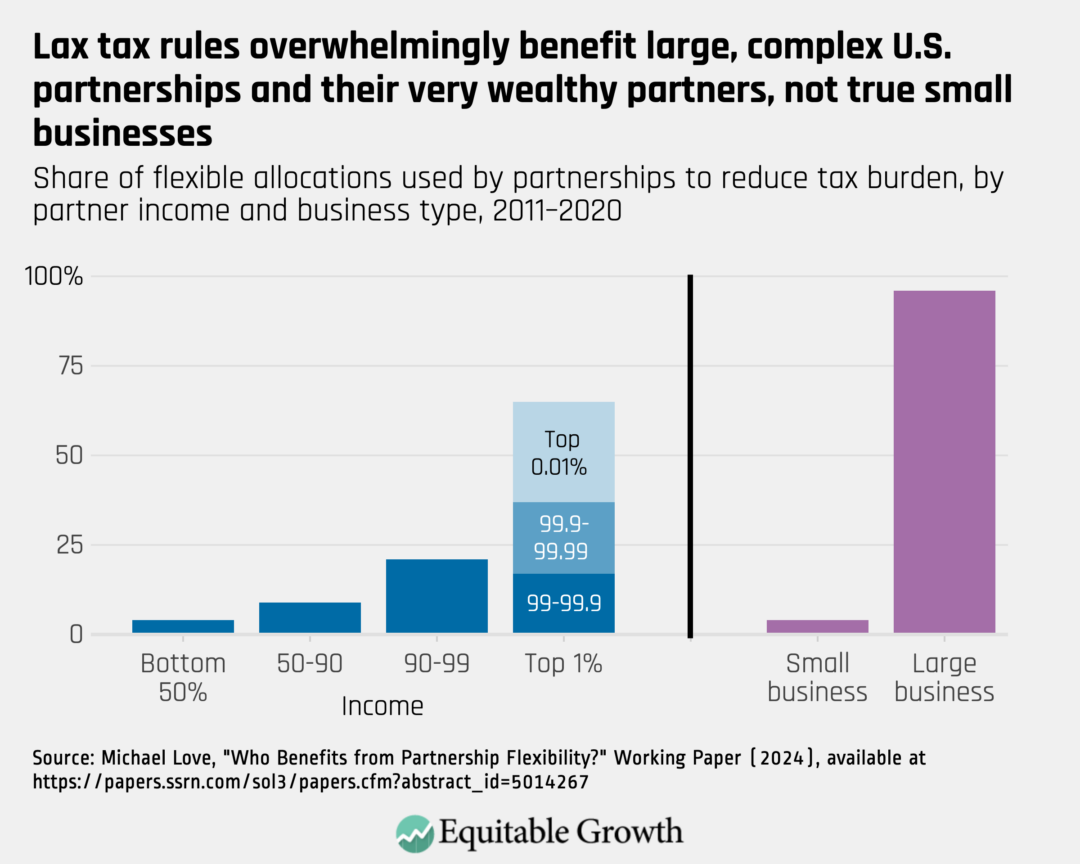

One general, paradoxical takeaway from this research is that smaller, less complicated firms that are often cited by policymakers as requiring flexible tax rules are generally not the ones taking advantage of those rules. Instead, large, complex real estate17 and finance companies are using these sophisticated maneuvers to help their high-income—and often foreign—owners avoid billions in U.S. taxes.

Let’s now review each of these tax avoidance strategies.

Flexible allocations of profits and loss

Columbia’s Love looks at which partnerships take advantage of the flexible allocation rules that give partners broad latitude to claim profit shares and tax deductions independent of their underlying ownership stake.18 (See Figure 5 below.) He compares the actual use of lax tax rules against the rules that would apply if these partnerships instead were treated as S corporations—in other words, if they were not able to deviate from capital contributions in allocating tax benefits to owners (i.e., taxable gains and losses passed through to partners directly in proportion to how much money they have invested).

According to Love, only 17 percent of firms each year flexibly allocate more than 1 percent of their allocations, while 12 percent of firms flexibly allocate at least 10 percent of their allocations. Only 9 percent of firms derive any tax benefit from flexible allocations. Yet Love finds that those few partnerships that do benefit from flexible allocations benefit handsomely, even by conservative estimates, seeing an average drop in their effective federal tax rate of 4 percentage points, or $331 billion of tax benefits between 2011 and 2020.19 These tax benefits are even more concentrated among high-income individuals than partnership income is generally, with 66 percent accruing to the top 1 percent and 28 percent accruing to the top 0.01 percent of the income distribution.

This $331 billion figure is not an estimate of new government revenue were flexible allocations no longer allowed. If Congress were to end the ability of partners to make flexible allocations, then these taxpayers would likely find other ways to reduce at least some of this new tax burden.

To be clear, these benefits also are not necessarily the result of illegal tax evasion. There are complicated rules that govern when allocations are allowed. Technically, business arrangements that do not reflect the economic reality of the enterprise and are being employed solely to avoid taxes are not legal. Yet this has proven to be a very difficult standard to enforce, and the IRS has struggled to crack down on suspected abuse.

Love also finds that 44 percent of U.S. partnerships could generate some tax benefits through flexible allocations but mostly do not—perhaps because they do not have the resources necessary to hire tax advisers that can help them with the sophisticated financial maneuvers required. This means that certain large, high-income firms are using tax planning rather than, say, providing better value to customers to gain a competitive advantage over their smaller, lower-income rivals.

Importantly, allocation rules are not the only source of tax flexibility, and possible tax noncompliance, among partnerships. Other tax avoidance schemes include disguised sales, related-party basis shifting, and taking deductions for personal expenses, none of which Love studies directly.20 Flexible allocations, however, are perhaps the most straightforward tax avoidance technique available to partnerships, so it is unlikely that the other forms of abuse would prove to be more prevalent.

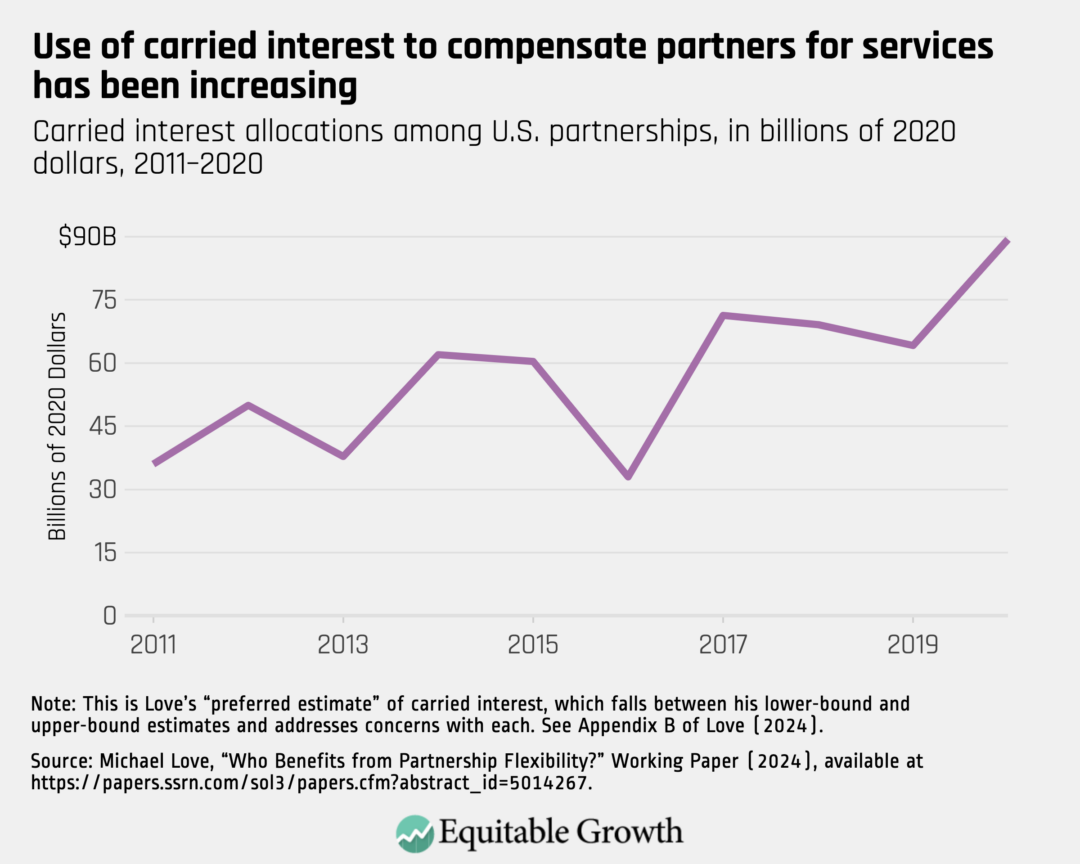

Carried interest

One of the most controversial partnership tax maneuvers that falls under the umbrella of Love’s flexible allocations is compensating partners for their labor with a “carried interest” in the capital gains and qualified dividends from the firm’s investments.21This effectively means that instead of being taxed at a 37 percent marginal rate on labor income, high-income partners can lower their tax rate to 20 percent—the highest long-term capital gains and qualified dividends rate.22 (See Figure 5 below.)

Though technically any partnership can allocate a “carry” interest to partners, very few take advantage of this option, according to Love. The 1 percent that do are almost exclusively financial firms, accounting for 97 percent of all carried interests allocated.

The tax benefits of this practice, as well as other types of incentive-based compensation schemes under the overarching category of “profit interests,”23 sum to $92 billion over 10 years. This seems to indicate that the U.S. Joint Committee on Taxation’s 2023 estimate that closing the carried interest loophole would save $63.1 billion over 10 years is on the conservative side—though, again, Love’s finding is not a revenue score, since it includes other types of profit interests and does not account for behavioral changes that might result from closing the loophole.24

Love finds that these tax benefits accrue overwhelmingly to high-income individuals, with 50 percent going to those in the top 0.1 percent and 30 percent accruing to the top 0.01 percent. The use of carried interest has been increasing in recent years, growing more than 9 percent annually on average.25 (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

Blocker corporations in tax havens

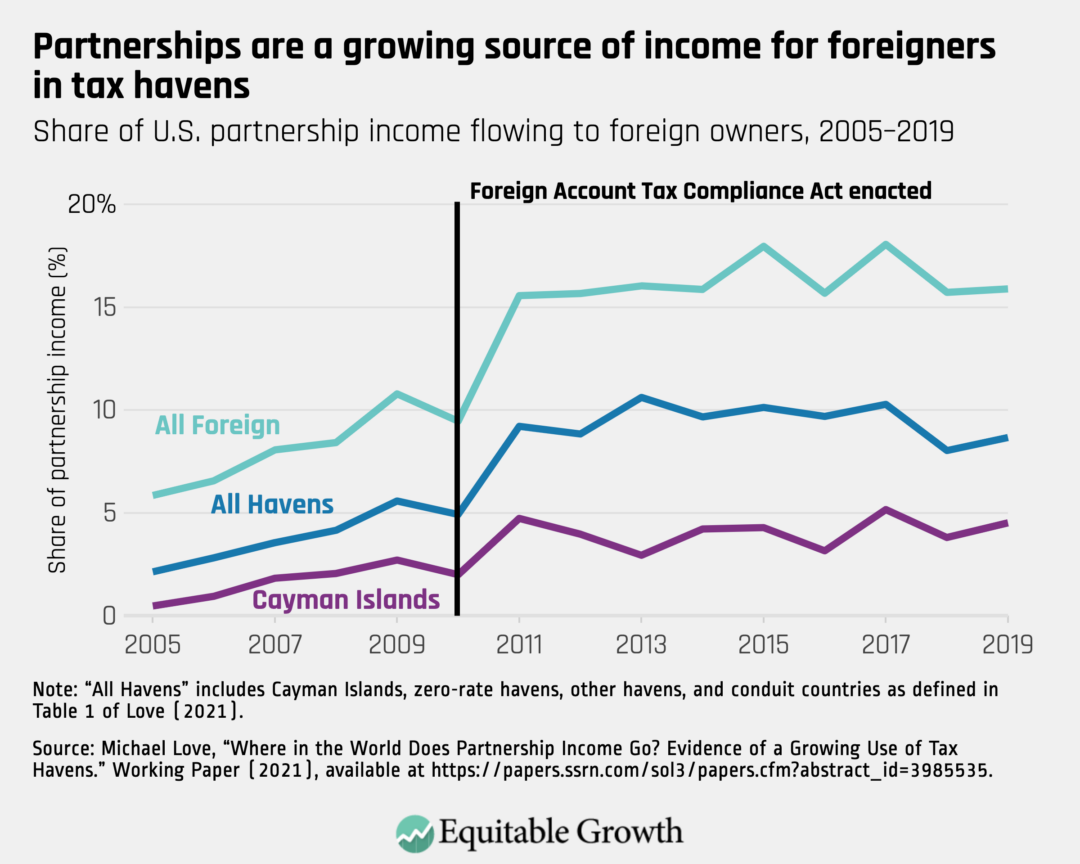

In previous work, Love used administrative tax records to trace the path of partnership income around the world. What he found was alarming: “Large amounts of passive investment income flowing tax-free from the U.S. to anonymous investors shielded by entities in tax havens.”26

This practice is especially prevalent among hedge funds, which take advantage of flexible tax rules to assign partial ownership of the partnership to what are known as blocker corporations in tax havens, such as the Cayman Islands. Blocker corporations essentially are foreign corporations used to conceal the identity and income of certain partnership owners from U.S. tax authorities.

Tax-exempt investors, such as U.S. pension funds, university endowments, and foundations, invest in the hedge fund through the blocker corporation to avoid unrelated business income tax, or UBIT, a tax on certain portions of a tax-exempt individual’s income that is generated from nonexempt activities. If not for the foreign blocker, UBIT would be triggered if the partnership’s investments are acquired using debt, a common practice among hedge funds and other sophisticated investment vehicles. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

Additionally, foreign investors use blocker corporations to ensure that they do not have to file U.S. tax returns and, potentially, to convert the partnership’s income into a type that is tax-preferred in their home country.

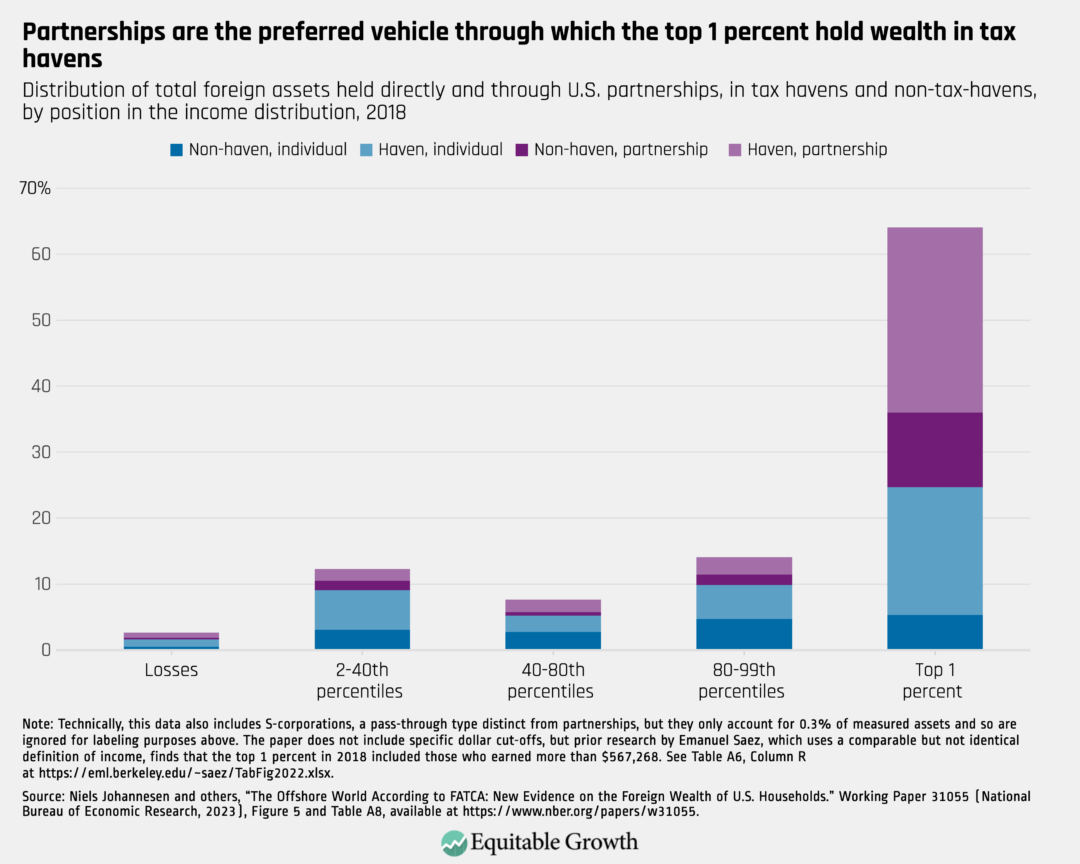

Researchers recently learned more about these arrangements as a result of the 2010 Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, which has begun to reveal through stricter reporting requirements just how much partnership income, which is overwhelming earned by those at the top of the income spectrum, flows through tax havens.27 (See Figures 6 and 7.)

Figure 6

Figure 7

Love’s latest paper corroborates some of these findings, demonstrating that firms with tax haven partners tend to use more flexible allocations and achieve lower tax rates as a result.

More stringent rules and more targeted enforcement would raise considerable revenue

Because large, complex partnerships use the most aggressive tax avoidance strategies, they also deserve the most IRS scrutiny. Hess and his co-authors find that if the IRS better targeted large, complex partnerships for audit, it would raise considerable revenue—to the tune of $20 for every $1 spent. (See Figure 8.)

Figure 8

This return on investment is considerably larger than other researchers have found when investigating IRS audit policy of other types of taxpayers and represents a nearly unprecedented return on public investment.28 Unfortunately, the IRS has not been able to aggressively audit large, complex partnerships in recent years because of a dearth of resources and because auditing such firms can be incredibly onerous.

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, in tax year 2019, a mere 54 large partnerships—those defined as having $100 million or more in assets and 100 or more total partners—were audited out of a total of 20,052.29 (See Figure 9.) Even President Trump’s web of partnerships escaped a thorough audit during his first term due in part to its complexity, even though the IRS is supposed to review sitting presidents’ returns.30

Figure 9

Hess and his co-authors also find that an inordinate number of audits of large, complex partnerships are almost immediately closed without any assessment, probably because examiners quickly realize they won’t have the time or expertise to unravel the full extent of the partnership’s tax compliance. When examiners are able to dedicate the necessary resources to the audit of large, complex partnerships, they tend to find major instances of noncompliance, which could be intentional evasion, overly aggressive position-taking in a gray area of tax law, or honest mistakes.

These findings are consistent with findings from the U.S. Government Accountability Office,31 as well as other research32 from Equitable Growth Nonresident Scholar Daniel Reck of the University of Maryland, Equitable Growth grantees Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley and Max Risch at Carnegie Mellon University, and researchers at the IRS. Reck and his co-authors find that random IRS audits, which are used to measure the tax gap and income inequality, miss a large amount of avoidance and evasion happening through pass-through businesses and offshore accounts among very-high-income households.33

That same study also finds that when auditors encounter pass-through income during an individual random audit, the auditor very rarely audits the pass-through business itself, ignoring a potential major source of noncompliance. The authors conservatively estimate that increased enforcement to close the income tax gap for the top 1 percent could yield a whopping $175 billion in currently uncollected income tax revenue per year. Other researchers have reached similar conclusions.34

Effects of enforcement on bona fide small businesses

According to Love, very few of the complex partnerships taking advantage of lax rules to lower their tax liability are truly “small businesses,” despite the political rhetoric often deployed in debates about pass-throughs more generally. He tests this by defining a bona fide small business as one that:

- Earns less than $5 million of net income or loss

- Has 50 or fewer partners, all of which are individuals

- Includes no more than three partnerships in the group, with no circular structures

- Has at least 75 percent of the partnership income or loss as operating or rental income or loss, as opposed to investment income

- Has no owners who are in the top 0.01 percent of income earners

- Does not use a profits interest to allocate portfolio investment income to partners

Under this detailed definition, Love finds that just 2.7 percent of the tax benefits he identifies as coming from flexible allocations, or $8.1 billion over 10 years, accrue to actual small businesses. Indeed, only 9.6 percent of all partnership income and loss accrues to bona fide small businesses. This is the case even though 66.2 percent of partnerships are small businesses, according to Love’s calculations. (See Figure 10.)

Figure 10

Even though most large, complex partnerships are not community-minded mom-and-pop small businesses, but rather real estate and investment firms enjoying exceedingly low tax rates and lax tax enforcement, it is likely that efforts to crack down on these firms will generate “trickle-down”-style arguments.35 That is, claims that increasing these firms’ tax burdens will slow economic growth and degrade the attractiveness of the United States as a destination for foreign investment.

Those arguments are without merit. Instead of spurring economic prosperity, there is evidence that growth in the financial sector crowds out real economic growth.36 This is part of a larger, troubling financialization of the U.S. economy.37 There is also emerging research that finds that the rise of pass-through firms, such as partnerships, has been bad for efficiency, growth, and employment because it keeps productive businesses capital-constrained.38

There is mixed evidence on the specific effect of hedge funds,39 private equity,40 and venture capital41 on the overall economy. It is possible that, rather than deploying capital to the most innovative and productive firms, these investment vehicles mostly engage in speculation, financial engineering, and rent-seeking. The large, heavily leveraged, short-term bets many of these firms, especially hedge funds, make have the potential to destabilize the macroeconomy, while the partners themselves are protected from personal liability, thanks to government-provided shields.42

Indeed, there is correlational evidence that as more partnership owners gained liability protection over the past few decades through the expanded use of limited liability companies and limited partnerships, allowing the partnership to take on debt without risking the partners’ personal assets, leverage ratios increased.43 According to Hess and his co-authors, 81 percent of partnerships have some form of limited liability structure.

More importantly for policymaking purposes, there is little empirical evidence on how the tax treatment of these firms might alter their investments. If anything, though, the ongoing research points to tax policies that are overly generous to financial firms, especially private equity businesses that rely heavily on tax-preferred debt.44

As Love points out in his 2021 paper on partnerships and tax havens, it is highly unlikely that the United States needs to offer tax-haven-style policies to foreign investors to remain the world’s preeminent financial capital. The U.S. dollar is the global reserve currency, and U.S. capital markets are the envy of the world.

Finally, raising revenue from the high-income owners of large, complex partnerships is also efficient from a social welfare perspective. This revenue could be put toward funding critical, pro-growth public investments, such as climate change mitigation or universal child care, with dollars that would otherwise deliver low marginal utility to their owners.

Policy implications

While there is still more to learn about the relationship between partnership ownership structures and tax compliance, the findings above should start to move policymakers in a few distinct directions. Namely, policymakers should consider closing loopholes in the tax treatment of partnerships, increasing and reforming tax law enforcement, imposing user fees, and enabling better reporting.

Let’s discuss each in turn.

Closing partnership tax loopholes

It has long been argued that partnerships need the flexibility embedded in Subchapter K, the section of the Internal Revenue Code that deals with partnerships, to remain economically dynamic, innovative, and nimble. But the research above shows that such flexibility, which has led to a notoriously complicated thicket of hard-to-navigate rules and unauditable business organizations, is not actually used very widely.

Doing away with some of the extreme flexibility in partnership tax rules will reduce the opportunity for tax avoidance without affecting the majority of partnerships, including bona fide small businesses. As such, closing loopholes by creating more bright-line rules and restricting flexibility, as some legal experts45 and policymakers46 have called for, will not have dire economic consequences.

Furthermore, more recent tax provisions that have made partnership tax—and pass-through tax more generally—even more complicated and generous, such as the Section 199A qualified business income deduction, should be allowed to expire at the end of 2025.47

Increasing tax law enforcement

Targeting audits toward the largest, most complex partnerships is likely to raise substantial revenue and do so in a progressive way because the vast majority of the firms taking advantage of lax tax rules are investment and real estate funds owned by the wealthy. In addition, reducing the incentive for firms to expend resources on wasteful tax planning is economically efficient.

As such, this policy intervention is consistent with true pro-growth tax reform.48 To be successful, this enhanced scrutiny must be coupled with increased appropriations for the IRS, in part so that the agency can hire auditors with the necessary, highly technical expertise. Recognizing the problem, the IRS earmarked some of its recent appropriations for these purposes, creating a new pass-through compliance unit and a Large Partnership Compliance program.49 Policymakers should not undo this progress.

Reforming enforcement

Noting the unique ways in which high-income Americans avoid taxes and the need for greater deterrence, some outside experts have argued persuasively for means-adjusting tax compliance rules.50 For instance, charging higher-income taxpayers higher penalties when they understate their income or are found to have taken an untenable position on their return would likely discourage aggressive avoidance strategies. So, too, would extending statutes of limitations for high-income taxpayers, giving auditors more time to review the especially complicated cases.

With Congress’ help, the IRS also could crack down on high-income taxpayers who hire tax advisers to provide written tax opinions to shield them from noncompliance penalties.51

Imposing user fees

One way to fund these enhanced enforcement efforts is via user fees on large, complex partnerships. These partnerships take advantage of government-provided liability protection and tax flexibility, so asking those firms to chip in to help pay for their own regulation—similar to how drug companies pay the U.S. Food and Drug Administration user fees—is justified.

One specific idea would be to charge wealthy partners (with adjusted gross incomes above, say, $400,000) a nominal $500 “complexity fee” if any of the partnerships in which they have an interest have more than five tiers of ownership, each of which has at least one nonindividual owner, such as an S corporation, C corporation, another partnership, or a trust. This would require some additional reporting and might ensnare some partners who are unaware of the complicated structures used by their investment managers.

Yet it also would discourage unnecessary complexity, while the proceeds could go directly to the IRS for audits of complex partnerships, creating a politically insulated funding stream for this important government function. According to Hess and his co-authors, even the average complex partnership only has two ownership tiers, so this user fee would only hit owners of the most complicated—and thus difficult to audit—webs of firms.

Enabling better reporting

Part of why researchers have struggled to fully understand who owns partnerships and why the IRS has struggled to conduct timely and thorough audits of the most complicated firms is that reporting requirements for these business structures are relatively light. Each partnership, for example, must file a Schedule K-1 for each partner that shows that partner’s share of the partnership’s earnings, but there is no requirement for the partnership to specify if the partner’s share emanates from a special allocation, such as carried interest. This would be a simple improvement.

It would also be fairly straightforward and incredibly helpful for the partnership to file an organizational chart with its tax return. This would allow researchers and enforcers to more easily trace lines of ownership, rather than trying to piece them together in the dark.

Partnerships also should be required to specify the tax identification number of all of their “beneficial owners,” a legal term of art that means the real persons at the end of the full ownership string.52 This would help researchers and government auditors fully understand who is using these elaborate structures, no matter how many cryptic-sounding LLCs, shell companies, financial intermediaries, or blocker corporations are being employed to keep authorities off the scent.53

Conclusion

The tax rules governing companies organized as partnerships have not changed much in the past 50-plus years, but the types of firms forming as partnerships and taking advantage of those rules has. Rigorous academic research shows that the rise of large, complex partnerships in the real estate and finance industries has meant an explosion in tax avoidance strategies that drain government coffers in ways not anticipated by the writers of our tax code decades ago.

These strategies include schemes that move income from higher-taxed partners to lower-taxed partners and from higher-tax years to lower-tax years, convert the labor income of investment managers to capital gains, and exploit tax havens to hide what would otherwise be taxable income for tax-exempt organizations, among other sophisticated techniques.

These strategies take advantage of an overly flexible and lenient partnership tax structure, which some argue is necessary for keeping the U.S. small business sector dynamic, innovative, and nimble. But recent research belies this claim. The beneficiaries of the aforementioned flexibility are almost entirely large real estate and financial firms and their very high-income owners—not bona fide small businesses.

Policymakers should consider this good news because it means that cracking down on these costly practices will not harm low- or middle-income taxpayers, small U.S. firms, or the broader U.S. economy. Indeed, more targeted audits by a fully resourced IRS will easily pay for themselves and in fact will raise considerable federal revenue—a rare win-win.

About the author

David S. Mitchell is a senior fellow for tax and regulatory policy at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. Prior to joining Equitable Growth, Mitchell was the associate director for policy and market solutions at the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program. He previously worked as a legislative aide to U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), handling health care and Social Security issues and working on the landmark health reform law that passed in 2010. Mitchell also has held positions with the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, the White House National Economic Council, the law firm Hogan Lovells, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, Citizens for Tax Justice, and the National Association of Community Health Centers. He holds a B.A. in political science from Tufts University, an M.P.A. from the School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University, and a J.D. from the Georgetown University Law Center, where he was a Public Interest Law Scholar.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this report were inspired in part by a National Tax Association panel that the Washington Center for Equitable Growth organized on “Better Understanding the Economic and Revenue Consequences of Complex Partnerships.” The author would like to thank the participants and attendees of that panel discussion for their thoughtful contributions, including Sebastian Dyrda, Ryan Hess, Michael Love, Max Risch, and Steve Utke. The author also thanks Corey Husak, Miles Johnson, and Becky Lester for helpful comments. All errors are the author’s alone.

End Notes

1. Before the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which limited the use of passive losses and lowered tax rates, partnerships were also often used as tax shelters.

2. David S. Mitchell, “Factsheet: What the research says about taxing pass-through businesses” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2024), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/factsheet-what-the-research-says-about-taxing-pass-through-businesses/.

3. The differences between these legal forms are beyond the scope of this report, but they revolve around the degree to which partners are protected from personal liability for a firm’s debts under state law. All U.S. partnerships fall into one of these four categories.

4. Jason DeBacker and Richard Prisinzano, “The Rise of Partnerships,” Tax Notes Today, July 2, 2015, available at https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/partnerships-and-other-passthrough-entities/rise-partnerships/2015/07/02/fw1y.

5. Michael Cooper and others, “Business in the United States: Who Owns It, and How Much Tax Do They Pay?” Tax Policy and the Economy 30 (1) (2016), available at https://eml.berkeley.edu/~yagan/BusinessOwnersTaxes.pdf.

6. Corey Husak, “The sources and size of tax evasion in the United States” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-sources-and-size-of-tax-evasion-in-the-united-states/.

7. Paul Kiel, “How a Decades-Old Loophole Lets Billionaires Avoid Medicare Taxes,” ProPublica, December 11, 2024, available at https://www.propublica.org/article/medicare-tax-loophole-steve-cohen.

8. Matthew Smith and others, “The Rise of Pass-Throughs and the Decline of the Labor Share.” Working Paper 29400 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021), available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w29400/w29400.pdf.

9. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Large Partnerships: With Growing Number of Partnerships, IRS Needs to Improve Audit Efficiency,” GAO-14-732 (2014), available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-14-732.

10. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Tax Enforcement: IRS Audit Processes Can Be Strengthened to Address a Growing Number of Large, Complex Partnerships,” GAO-23-106020 (2023), available at https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-106020.

11. Ryan Hess and others, “The Spiderweb of Partnership Tax Structures.” Working Paper (Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2025), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/working-papers/the-spiderweb-of-partnership-tax-structures/.

12. Michael Love, “Who Benefits from Partnership Flexibility?” Working Paper (2024), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5014267.

13. According to the Congressional Budget Office, total federal revenue between 2011 and 2020 was $30.6 trillion. Congressional Budget Office, “Historical Budget Data” (n.d.), available at https://www.cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data#2.

14. Penn Wharton Budget Model, “Total Cost of Universal Pre-K, Including New Facilities” (2022), available at https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2022/6/2/total-cost-of-universal-pre-k.

15. In some cases, the two papers, by Hess and co-authors and by Love, refer to “partnerships” but actually mean a “group” or “organization” of partnerships since some firms use multiple partnerships to conduct their businesses. The papers have different methodologies for grouping related partnerships together, as opposed to identifying partnerships that have tiered ownership structures and other tentacles, but those statistical techniques are outside the scope of this report.

16. The number of complex partnerships in the finance and insurance industry, according to Hess and co-authors, is probably understated because many of those firms, including private equity firms, were dropped from the sample as a result of being part of a very large—and statistically unwieldy—organization (with more than 1 million nodes).

17. In addition to the tax flexibility that comes with partnership status, real estate investors also benefit from various special provisions in the code, including Sec. 1031’s like-kind exchanges, Sec. 465’s exception to the at-risk rule for nonrecourse real estate loans, depreciation and the depreciation recapture tax, and the “real estate professional” loophole. See Steve Wamhoff, “How True Tax Reform Would Eliminate Breaks for Real Estate Investors Like Donald Trump” (Washington: Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2017), available at https://itep.org/how-true-tax-reform-would-eliminate-breaks-for-real-estate-investors-like-donald-trump/; Thomson Reuters Tax & Accounting, “What accountants need to know about rental property tax depreciation,” August 25, 2023, available at https://tax.thomsonreuters.com/blog/what-accountants-need-to-know-about-rental-property-tax-depreciation/; Alicia Tuovila, “What is Depreciation Recapture?” Investopedia, November 5, 2024, available at https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/depreciationrecapture.asp; John H. Skarbnik, “Real Estate Professionals: Avoiding the Passive Activity Loss Rules,” The Tax Adviser, July 1, 2014, available at https://www.thetaxadviser.com/issues/2014/jul/skarbnik-july2014.html.

18. Technically, these allocation decisions must be made without knowledge of how much or which type of income the partnership will produce.

19. One particularly aggressive type of flexible allocation is a so-called arbitrage allocation, which effectively swaps types and amounts of income between partners and across time to lower partners’ tax liabilities—for example, allocating tax losses to partners with otherwise-high tax liability or allocating taxable gains to partners in low marginal tax brackets or who are tax-exempt. Love finds that arbitrage allocations produced $119 billion in tax savings for partnerships between 2011 and 2020, which means they account for 36 percent of the $331 billion in benefits that come from flexible allocations overall.

20. For a comprehensive list and further explanation, see Miles Johnson and others, “Modernizing partnership taxation” (Washington: The Hamilton Project, 2024), available at https://www.hamiltonproject.org/publication/policy-proposal/modernizing-partnership-taxation/.

21. This is sometimes achieved through management fee waivers. For more on that topic, see Gregg D. Polsky, “A Compendium of Private Equity Tax Games.” UNC Legal Studies Research Paper 2524593 (2014), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2524593.

22. For simplicity, neither of these numbers includes the possible application of payroll taxes, the self-employment tax, the net investment income tax, or the additional Medicare tax.

23. For Love’s purposes, carried interest is a subset of what is known as a profit interest, though not all tax practitioners make this distinction. Whereas carried interest for Love allocates capital gains and dividends to certain partners in exchange for labor services, partnerships can also allocate other income types, such as ordinary business profits, as a form of incentive-based compensation to service providers. The latter is less nefarious because there tends to be no tax rate difference between ordinary business income received as a partner and ordinary labor income received as a service provider. Love is able to differentiate between the two for the purposes of his allocation calculations but not for the purposes of his overall tax benefit calculation. It is likely, however, that the lion’s share of the $92 billion in tax benefits that he determines emanates from profit interests are, in fact, due to carried interest.

24. Sen. Ron Wyden, “Ending the Carried Interest Loophole Act” (n.d.), available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/ending_the_carried_interest_loophole_act_one_pager.pdf.

25. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 marginally tightened the carried interest loophole, requiring a 3-year holding period for capital assets to receive long-term capital gain treatment by certain partners rather than the normal 1-year holding period requirement. Partnerships did not have to comply with this new rule until 2021, so Love’s analysis, which only goes until 2020, does not speak to the potential impact of that provision.

26. Michael Love, “Where in the World Does Partnership Income Go? Evidence of a Growing Use of Tax Havens.” Working Paper (2022), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3985535.

27. Niels Johannesen and others, “Taxing Hidden Wealth: The Consequences of U.S. Enforcement Initiatives on Evasive Foreign Accounts.” Working Paper (2018), available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59ae6e08914e6b4040aa9716/t/5cd59095ec212d589c659a01/1557500064798/FBAR.pdf; Niels Johannesen and others, “The Offshore World According to FATCA: New Evidence on the Foreign Wealth of U.S. Households.” Working Paper (2023), available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/59ae6e08914e6b4040aa9716/t/6411df1d8793ef3e496197f8/1678892829665/FATCA-descriptive.pdf.

28. Will C. Boning and others, “A Welfare Analysis of Tax Audits Across the Income Distribution.” Working Paper (2023), available at https://scholar.harvard.edu/hendren/publications/welfare-analysis-tax-audits-across-income-distribution.

29. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Tax Enforcement: IRS Audit Processes Can Be Strengthened to Address a Growing Number of Large, Complex Partnerships.”

30. U.S. Joint Committee on Taxation, “Report to the House Committee on Ways and Means Chairman Richard Neal” (2022), available at https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23476433-jct-report-final/.

31. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Tax Enforcement: IRS Audit Processes Can Be Strengthened to Address a Growing Number of Large, Complex Partnerships.”

32. Daniel Reck, Max Risch, and Gabriel Zucman, “Tax evasion at the top of the U.S. income distribution and how to fight it” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/tax-evasion-at-the-top-of-the-u-s-income-distribution-and-how-to-fight-it/.

33. John Guyton and others, “Tax Evasion at the Top of the Income Distribution: Theory and Evidence.” Working Paper 28542 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023), available at https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w28542/w28542.pdf.

34. Natasha Sarin and Lawrence H. Summers, “Shrinking the Tax Gap: Approaches and Revenue Potential.” Working Paper 26475 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2019), available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w26475; Jeanne Bomare and Daniel Reck, “Fighting tax evasion by the wealthy can raise revenue and restore the integrity of the U.S. tax system” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2022), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/fighting-tax-evasion-by-the-wealthy-can-raise-revenue-and-restore-the-integrity-of-the-u-s-tax-system/.

35. U.S. Chamber of Commerce, “Large Private Companies Strengthen Communities Across America” (2024), available at https://www.uschamber.com/economy/large-private-companies-strengthen-communities-across-america.

36. Stephen G. Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi, “Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth?” Working Paper 490 (Bank for International Settlements, 2015), available at https://www.bis.org/publ/work490.pdf.

37. Amanda Fischer, “The rising financialization of the U.S. economy harms workers and their families, threatening a strong recovery” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2021), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-rising-financialization-of-the-u-s-economy-harms-workers-and-their-families-threatening-a-strong-recovery/.

38. Mitchell, “Factsheet: What the research says about taxing pass-through businesses.”

39. Vikas Agarwal and Honglin Ren, “Hedge Funds: Performance, Risk Management, and Impact on Asset Markets,” in Oxford Research Enclyclopedias: Economics and Finance (2023), available at https://oxfordre.com/economics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-841.

40. Steven J. Davis and others, “The (Heterogeneous) Economic Effects of Private Equity Buyouts.” Working Paper 2019-122 (Becker Friedman Institute, 2021), available at https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/BFI_WP_2019122.pdf.

41. Sabrina Howell and others, “Financial Distancing: How Venture Capital Follows the Economy Down and Curtails Innovation.” Working Paper (2020), available at https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/files/covidpt/files/financial_distancing.20200505.pdf.

42. Lloyd Dixon, Noreen Clancy, and Krishna B. Kumar, “Do Hedge Funds Pose a Systemic Risk to the Economy?” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2012), available at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9680.html.

43. DeBacker and Prisinzano, “The Rise of Partnerships.”

44. See, for example, Jordan Richmond, “The Distributional Consequences of Private Equity” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2024), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/grants/the-distributional-consequences-of-private-equity/ (preliminarily showing, in an unpublished presentation shared with the author, employment and wage declines at companies acquired by private equity firms); Arpit Gupta and Sabrina Howell, “The role of private equity in the U.S. economy, and whether and how favorable tax policies for the sector need to be reformed” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2023), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/the-role-of-private-equity-in-the-u-s-economy-and-whether-and-how-favorable-tax-policies-for-the-sector-need-to-be-reformed/; Karl Okamoto and Thomas J. Brennan, “Measuring the Tax Subsidy in Private Equity and Hedge Fund Compensation.” Drexel College of Law Research Paper 2008-W-01 (2008), available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1082943; Carolin Bock and Martin Watzinger, “The Capital Gains Tax: A Curse but Also a Blessing for Venture Capital Investment.” Working Paper (2017), available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jsbm.12373.

45. Johnson and others, “Modernizing partnership taxation.”

46. U.S. Senate Committee on Finance, “Wyden Unveils Proposal to Close Loopholes Allowing Wealthy Investors, Mega-Corporations to Use Partnerships to Avoid Paying Tax,” Press release, September 10, 2021, available at https://www.finance.senate.gov/chairmans-news/wyden-unveils-proposal-to-close-loopholes-allowing-wealthy-investors-mega-corporations-to-use-partnerships-to-avoid-paying-tax.

47. David S. Mitchell, “2017 tax cut for pass-through business owners exacerbated inequality and failed to deliver economic benefits” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2024), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/2017-tax-cut-for-pass-through-business-owners-exacerbated-inequality-and-failed-to-deliver-economic-benefits/.

48. Michael Linden, David S. Mitchell, and Shayna Strom, “The promise of equitable and pro-growth tax reform” (Washington: Washington Center for Equitable Growth, 2024), available at https://equitablegrowth.org/research-paper/the-promise-of-equitable-and-pro-growth-tax-reform/.

49. IRS, “IRS announces launch of pass-through compliance unit in LB&I; new group brings together teams of specialists from across the agency to tackle large or complex exams,” Press release, October 22, 2024, available at https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-announces-launch-of-pass-through-compliance-unit-in-lbi-new-group-brings-together-teams-of-specialists-from-across-the-agency-to-tackle-large-or-complex-exams; IRS, “IRS announces sweeping effort to restore fairness to tax system with Inflation Reduction Act funding; new compliance efforts focused on increasing scrutiny on high-income, partnerships, corporations and promoters abusing tax rules on the books,” Press release, September 8, 2023, available at https://www.irs.gov/newsroom/irs-announces-sweeping-effort-to-restore-fairness-to-tax-system-with-inflation-reduction-act-funding-new-compliance-efforts.

50. Joshua D. Blank and Ari Glogower, Untaxed: The Rich, the IRS, and a New Approach to Tax Compliance (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2025).

51. For more on this and other ways to means-test tax penalty defenses and reporting requirements, see Blank and Glogower, Untaxed.

52. Johnson and others, “Modernizing partnership taxation.”

53. See Spencer Woodman, “How investment firms shield the ultrawealthy from the IRS,” International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, April 3, 2024, available at https://www.icij.org/inside-icij/2024/04/how-investment-firms-shield-the-ultra-wealthy-from-the-irs/. The recently enacted Corporate Transparency Act represents one attempt by the U.S. Congress to get at this information for certain law enforcement purposes, but the law doesn’t apply to all the entities that often make up a large, complex partnership and does not apply to tax forms such as the Schedule K-1, making it of little use to the IRS or tax data researchers. Furthermore, a federal court is currently blocking the law’s implementation on constitutional grounds.

Related

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!