This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

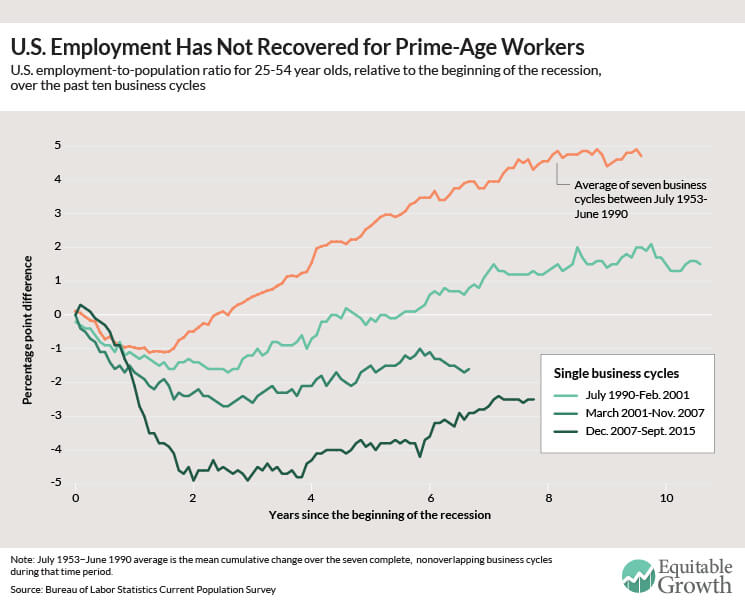

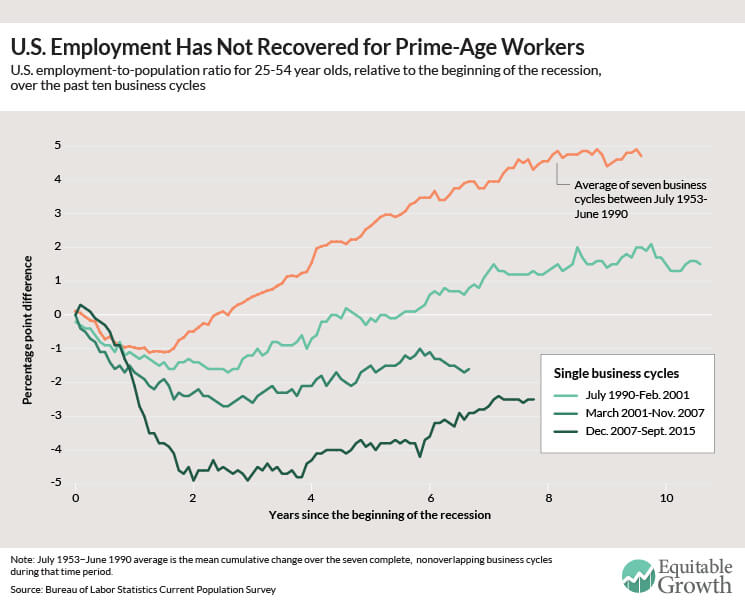

The unemployment rate is just above 5 percent, close to many economists’ estimates of its long-run level, but wage growth hasn’t picked up. Perhaps we need to look at new labor market measures. Enter: the Z-POP.

Wealth inequality in the United States is about more than the share of wealth captured by the top 0.1 percent of families—inequality by race and ethnicity is also quite profound. A new paper tries to understand the roots of the racial and ethnic wealth gap.

In our era of slow U.S. economic growth and declining productivity gains, many think that magic might be the only way to boost our future prospects. But while economists aren’t sure what exactly boosts growth, we aren’t entirely in the dark.

After the housing bubble burst during the Great Recession, the amount of time it took for a house to go through foreclosure increased significantly. Two economists show how these delays acted like an extension of credit, helping unemployed workers weather a lack of a job, and actually increased wages.

Links from around the web

“The effects of hysteresis — where recessions are not just costly but stunt the growth of future output — appear far stronger than anyone imagined a few years ago.” Larry Summers argues the case for expansion in an era of secular stagnation. [ft]

Recent debates about the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal and new research on the effects of trade are starting to crack an old consensus, says Noah Smith. “The simple logic of free trade, so familiar from Econ 101, is either failing or ceasing to be relevant.” [bloomberg view]

For decades, women in the United States participated in the labor market at rates that led the league tables for high-income economies. While women in Japan have historically participated in the labor market at much lower rates, their employment rate is now higher than the rate for U.S. women. Danielle Paquette looks into how this happened. [wonkblog]

If monopolies and market power have been increasing in the United States, does that have any influence on the decline in interest rates over the last several decades? Carleton University economist Nick Rowe looks into the possible connection. [worthwhile canadian initiative]

Policymakers, economists, and market participants have started to fear the global economy is slowing down. Digging out some charts from a report by Citibank, David Keohane sees inflation cooling off across the globe—and it’s not because of declining energy prices. [ft alphaville]

Friday figure

Figure from “Where is the U.S. labor market recovery for prime-age workers?” by Ben Zipperer.