Today, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, with Generation Progress and Higher Ed, Not Debt, released its interactive, Mapping Student Debt, which compares the geographic distribution of average household student loan balances and average loan delinquency to median income across the United States and within metropolitan areas. The stark patterns of student debt across zip codes enable us to begin to analyze the role that debt plays in people’s lives and the larger economy.

Delinquency and income

One element of the student debt story that has already been explored is that borrowers with the lowest student loan balances are the most likely to default because they are also the ones likely face the worst prospects in the labor market. Our analysis using the data displayed in the interactive map is consistent with these findings.

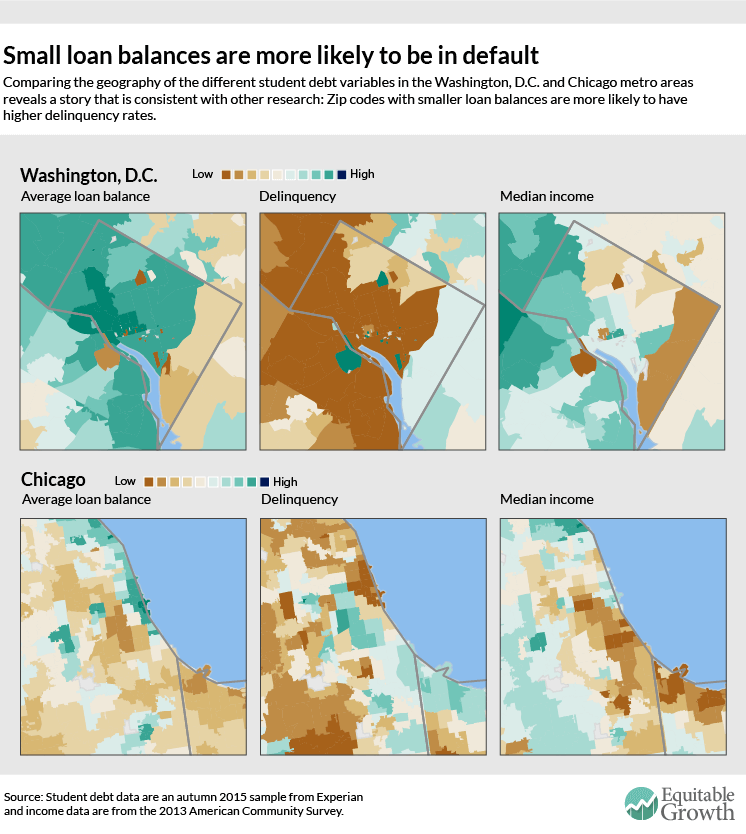

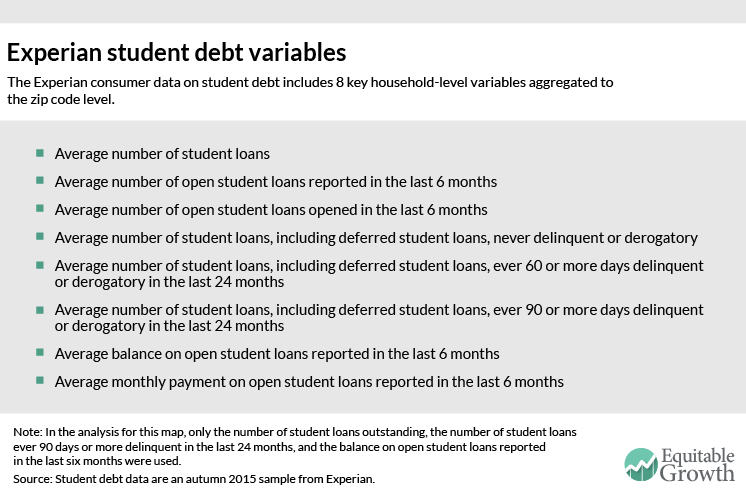

The geography of student debt is very different than the geography of delinquency. Take the Washington, D.C. metro region. In zip codes with high average loan balances (western and central Washington, D.C.), delinquency rates are lower. Within the District of Columbia, median income is highest in these parts of the city. Similar results–low delinquency rates in high-debt areas–can be seen for Chicago, as well. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

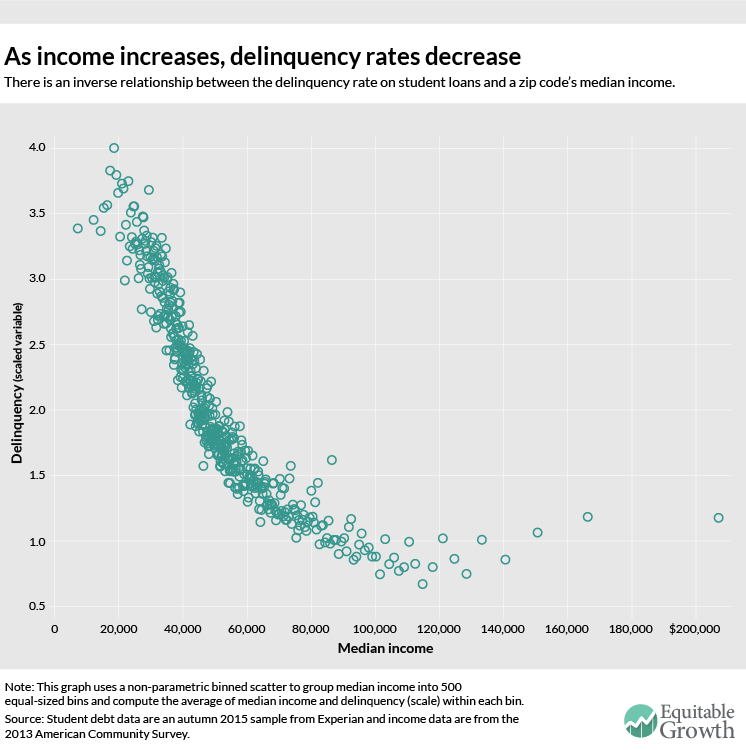

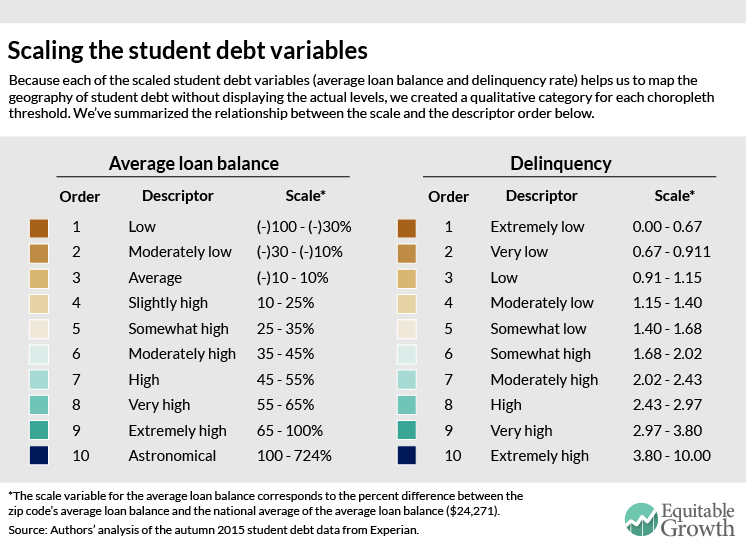

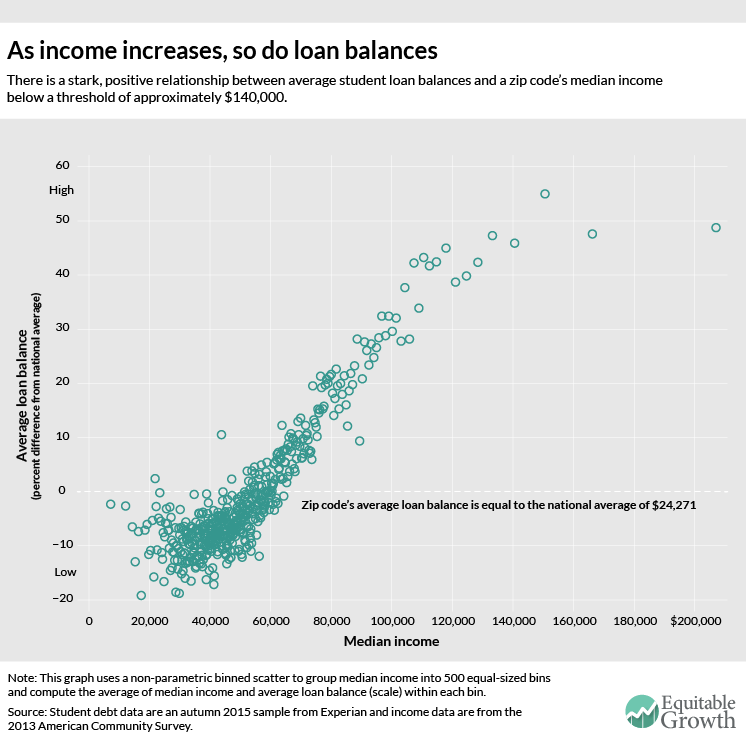

For the country as a whole, there’s an inverse relationship between zip code income and delinquency rates. As the median income in a zip code increases, the delinquency rate decreases, corroborating findings that low-income borrowers are the most likely to default on their loan repayments. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

What explains this relationship? There appear to be two possible, and mutually consistent, theories. First, although graduate students take out the largest student loans, they are able to carry large debt burdens thanks to their higher salaries post-graduation. One study of student loans by institution type reports a three-year cohort default rate for graduate-only institutions of 2 percent to 3 percent.* Second, the rise in the number of students borrowing relatively small amounts for for-profit colleges has augmented the cumulative debt load, but because these borrowers face poor labor market outcomes and lower earnings upon graduation (if they do in fact graduate), their delinquency rates are much higher. This is further complicated by the fact that these for-profit college attendees generally come from lower-income families who may not be able to help with loan repayments.

The inverse relationship between delinquency and income is not surprising, especially when considering that problems of credit access have disproportionately affected poor and minority populations in the past. In the 1930s, for example, the government-sanctioned Home Owner’s Loan Corporation labeled maps of American cities by each neighborhood’s worthiness for mortgage lending. Neighborhoods outlined in red were considered the least worthy, purposefully coinciding with their black and poor white populations. Banks and insurance agencies also adopted these discriminatory “redlining” practices, further cutting off communities from the essential capital that is needed to develop neighborhoods and invest in sustainable infrastructure. Though redlining was outlawed in the 1960s, its pernicious effects still persist, as seen in Figure 2 as well as in maps of the subprime mortgage crisis that began in 2006.

It might seem counterintuitive that lack of access to credit results in delinquency—seemingly a problem of “too much debt.” But in fact, lack of access to credit and delinquency are two sides of the same coin. Nearly everyone needs access to credit markets to meet basic economic needs, and if they can’t get loans through competitive, transparent financial networks, poor people are more likely to be subjected to exploitative credit arrangements in the form of very high rates and other onerous terms and penalties, including on student loans. That disadvantage interacts with and is magnified by their lack of labor market opportunities. The result is exactly what we see across time and space: high delinquency rates for those with the least access to credit markets.

Student loan balances and debt burdens

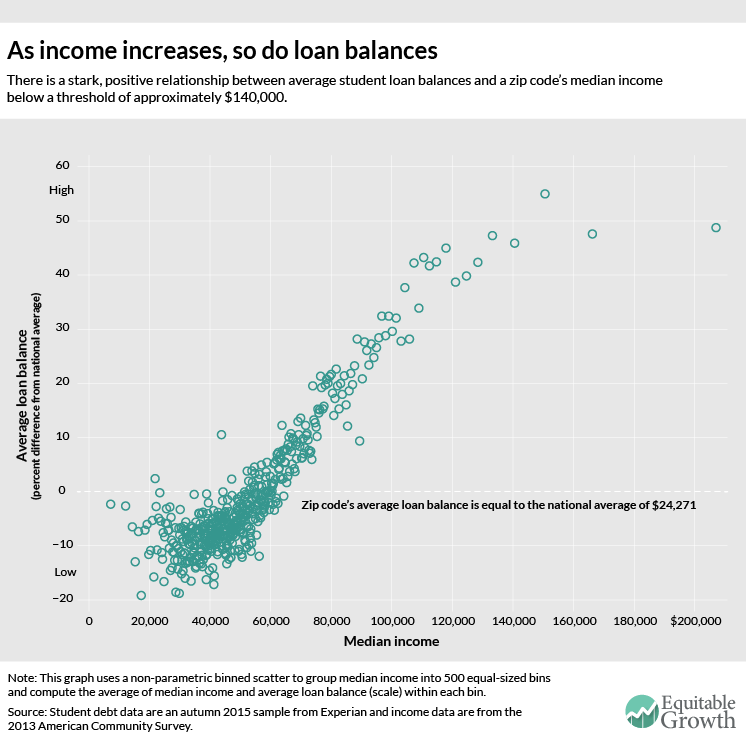

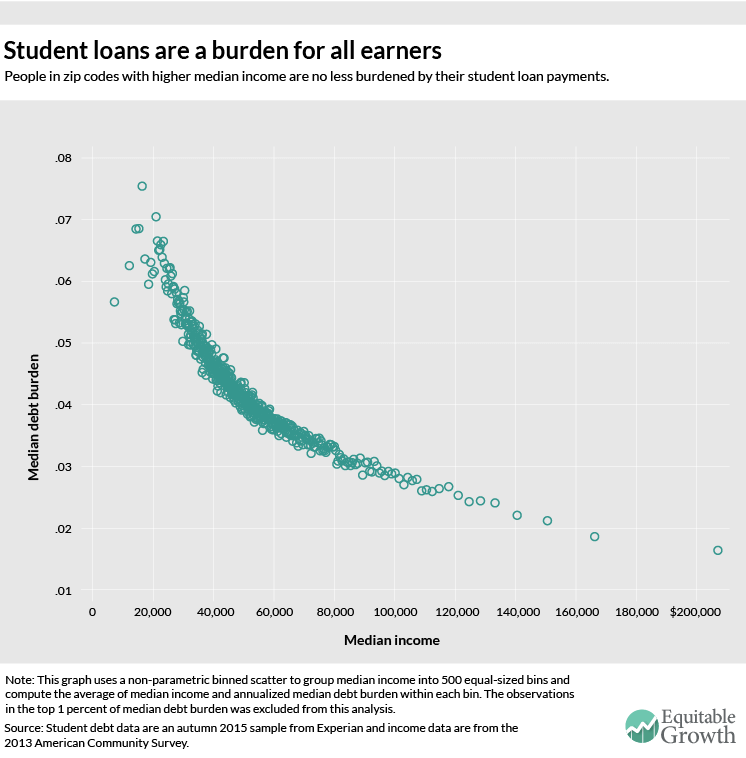

When we look at average loan balance and median income, we find a stark positive relationship, at least below a certain income threshold. As median income increases in a zip code, so does the average loan balance, until income reaches approximately $140,000. After that, the relationship becomes flat. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

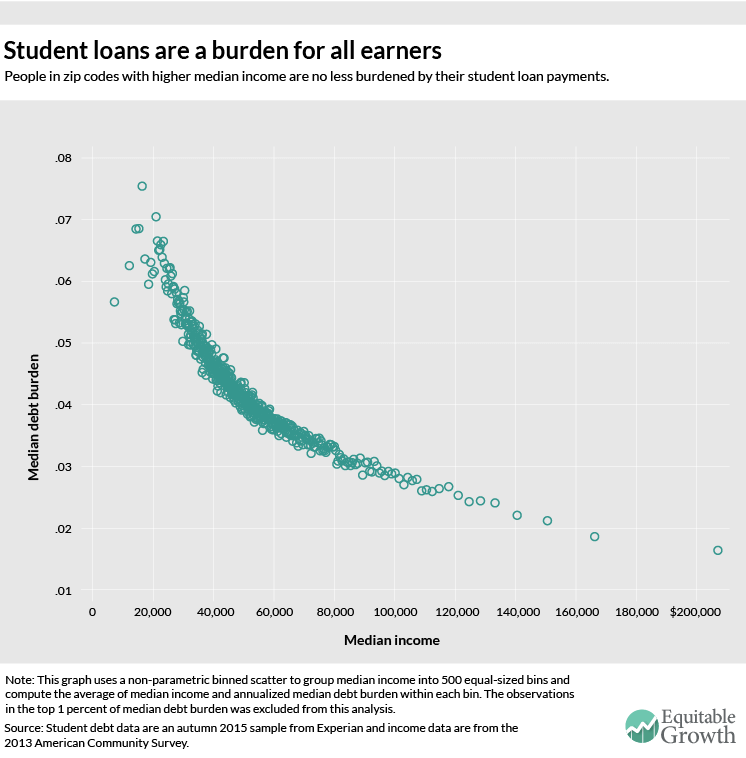

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the “burden” of student loan payments and zip code median income. Using the “average monthly payments on student loans” variable, we calculate that student debt absorbs around 7 percent of gross income in zip codes where median income is $20,000, declining to 2 percent in the highest-income zip code

Figure 4

These graphs show us that the burden of student debt isn’t just shouldered by the young. As borrowers age, servicing their student debt hinders their ability to accumulate wealth. In fact, the Pew Research Center found that college-educated householders with student debt have one-seventh the wealth of people without debt, in part because the wealthiest students don’t need to go into debt to pay for college. Student debt repayment may also delay expenditures that are associated with the traditional economic lifecycle, such as owning a home or a car or even getting married. Altogether, this new expense associated with attaining a middle-class income contributes to the erosion of middle-class wealth across generations.

As cumulative student debt continues to grow and we learn more about its role in the nation’s many economic problems, it is clear that a reconsideration of the policies that treat student debt as “good debt” because it finances valuable human capital is in order, especially in light of the problems that even young college graduates have in the labor market.

Methodology

This geographic analysis uses two primary datasets: credit reporting data on student debt from Experian and income data from the American Community Survey.

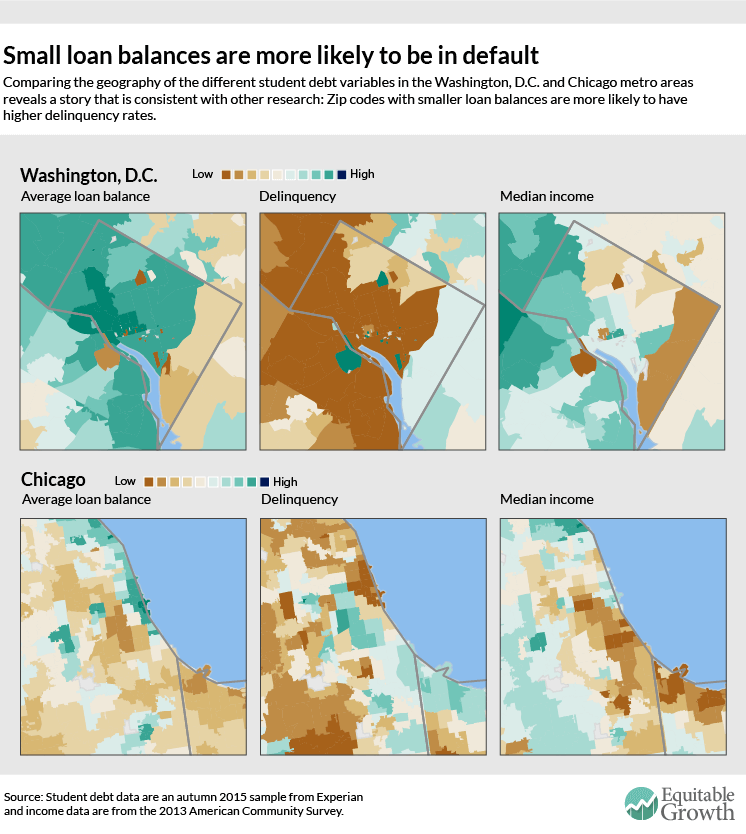

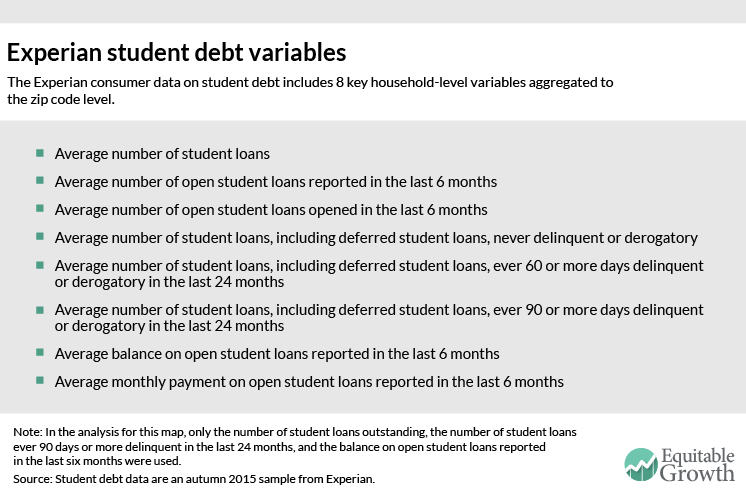

The Experian data includes eight key student debt variables (see Figure 5) aggregated from household-level microdata to the zip code level. The underlying household data are a snapshot of the entire U.S. population at a single point in time—in this case, the autumn of 2015.

Figure 5

There are a number of caveats regarding the Experian data file that have guided our methodology for constructing variables and analyzing results:

• The universe of households contains only those with “any type of credit” and which, therefore, have a credit report. Relative to the population as a whole, this likely excludes the poorest households without any official credit access whatsoever.

• It is unclear how Experian constructs “households” since credit reports pertain to an individual’s credit history.

• If the same student loan has more than one signatory, then the loan may be assigned to multiple households and hence to multiple zip codes or even counted more than once within the same household.

• Experian claims that the universe of their geographically-aggregated data is all households with credit, but the levels of the data on loan balance and delinquency are more consistent with the idea that the universe is only households that have student loans. In other words, Experian claims their data include households that have credit but no outstanding student loans, but if that is the case the reported levels for both average loan balance and average delinquency are much higher than other sources would suggest. Average loan balance and average delinquency rates, however, are comparable to reliable outside estimates if interpreted as loan balance and delinquency among only those households with student debt.

For these reasons, we do not report any student loan data in dollar amounts. Instead, we have used two of the Experian variables to construct analogs to relative average household loan balance and relative delinquency.

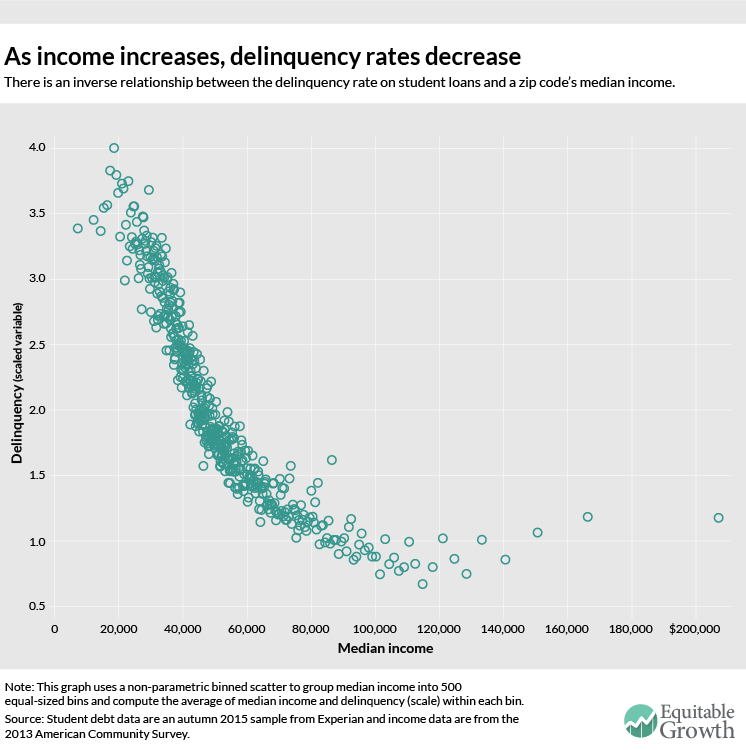

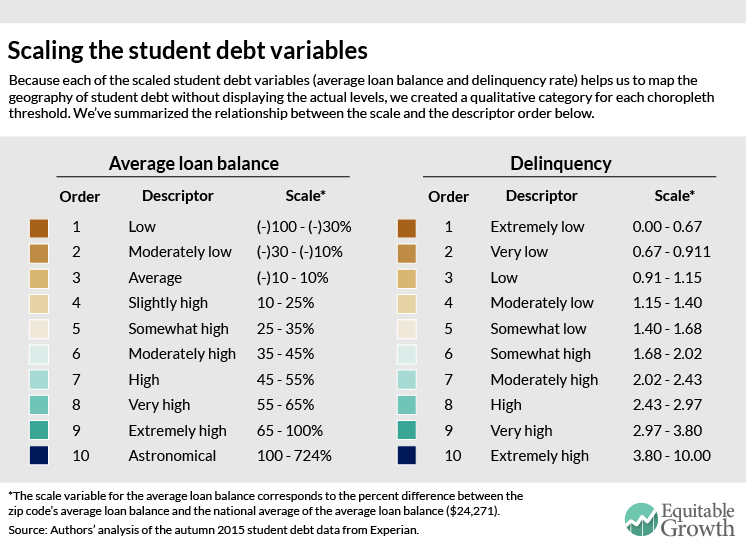

To create the average household loan balance variable in the interactive map, we calculate an “average of the average” zip code-level student loan balance for the entire country, then code zip codes by percentage above or below that average-of-averages. For delinquency, we calculate a “delinquency rate” for each zip code by dividing the average number of 90-or-more-days-delinquent loans per household by the average number of outstanding loans per household. Then, after winsorizing the top one percent of observations to the 99th percentile value, we project the “delinquency rate” onto a scale that ranges from 0 to 10.

For user-friendliness, we assign each of these student debt scale variables a qualitative category. If average loan balance on the map is “somewhat high,” for example, then it means that a zip code’s average loan balance is between 25 and 35 percent higher than the national average of $24,271. Similarly, if the delinquency reads “very low,” it corresponds to a scale level between 0.067 and 0.091. Figure 6 summarizes the relationship between each of the scale variables’ levels and their qualitative description.

Figure 6

Next, we merge zip code-level median income data from the 2013 American Community Survey with our imputed scaled student debt variables in order to construct choropleth maps.

The actual map uses three different techniques to display the variables on a choropleth scale. For the average loan balance, we artificially set ten cutpoints to enhance the geographic variation in metropolitan areas; to do this, we maximized the breadth of the color categories for values higher than the average-of-averages loan balance. For delinquency, we created ten quantiles (or equal counts) to account for the right-skewed data. Finally, for median income, we used ten jenks (or natural breaks in the data) to assign the color scale. Higher numbers and darker shading correspond to higher household average student loan balances, higher shares of outstanding loans that are 90 or more days delinquent in the previous 24 months, and higher median incomes. We think that the geographic variation in the Experian data (and as seen in the maps) is believable, but not the levels reported by Experian.

Download the “Mapping Student Debt” presentation from the December 1, 2015 release (pdf)

*Correction, December 8, 2015: A previous version of this column cited a Department of Education projected graduate student default rate of 7 percent, but the Department has removed that projection from its website and we now think the 2 percent to 3 percent realized default rate is a better estimate.