Must-read: Tim Duy: “Dudley the Dove”

Must Read: : Dudley the Dove: “Bottom Line: The Fed will take a pass on the March meeting…

…Whether the statement is dovish, neutral, hawkish is the key question. Dudley opens up the possibility of a not just a neutral statement, but a dovish one. My sense is that this is shaping up to be a very contentious meeting as participants struggle with the question of exactly which data are they dependent upon.

Why less job searching can be a good thing

Prior to the Great Recession of 2007-2009, eligible unemployed workers in the United States could receive unemployment insurance checks for up to 26 weeks. In the wake of the recession and the massive damage done to the labor market, however, the nation’s unemployment insurance program was extended so that workers could collect up to 99 weeks of benefits. Supporting workers when they can’t find a job makes sense, but some economists and policymakers were concerned that extending the program actually increased the amount of unemployment as workers searched less for a job. While workers on unemployment insurance did search less intensely during the recession, this reduction helped some unemployed workers find jobs.

There’s a wide body of research on the effect of unemployment insurance on the unemployment rate—and the vast majority of this research finds that unemployment insurance actually does increase the unemployment rate a small amount. But it’s important to note how it increases unemployment. By having some cash to allow them to take longer to find a job, workers will continue to show up as unemployed in the calculations of the unemployment rate. If they couldn’t find a job and stopped looking for work, they wouldn’t show up as unemployed according to the technical definition of unemployment. So by keeping workers in the job hunt, the unemployment insurance program pushes up the unemployment rate. It also allows workers to search less intensely and for a longer time, which increases the unemployment rate as well.

Just looking at how this program affects the individual worker’s unemployment status, however, is what economists might call a “partial equilibrium” analysis. In other words, the analysis hasn’t gone the next step to see how the micro-level change for each worker affects the macro level, or “general equilibrium.” Looking at the extension of unemployment insurance benefits in general equilibrium might show that the effect on unemployment is larger or smaller than looking just at the micro level.

A paper by University of Chicago economist Ioana Marinescu looks at just that question. (Here’s a summary of Marinescu’s paper at VoxEU.) Using data from the online job board CareerBuilder.com, Marinescu looks at how the extension of unemployment insurance affected total unemployment. She found that extended benefits reduced the intensity of job searching, measured by the number of job applications, but that the number of job openings posted didn’t change much. The result: less competition for the available jobs, increasing the probability that an unemployed worker could get a job.

The extended unemployment insurance benefits, in essence, tightened the labor market. The program, by inducing some workers to search less, made it seem like there were fewer unemployed workers and made the overall labor market seem more like one during an economic expansion. The macro effect of the extended benefits reduces the impact of the micro effect on the overall unemployment rate. According to Marinescu’s results, a 10 percent increase in the duration of unemployment insurance benefits only increased total unemployment by 0.6 percent. Including the macro effects pushes down the effect of unemployment insurance on unemployment by 40 percent.

While this result is a good reminder to not look at the effect of a program in isolation, it’s also further proof that helping unemployed workers during downturns isn’t just something that feels good—it’s something that has some real economic logic behind it.

Give working women their due for caregiving in economic policy debates

Economists love their economic models and their footnote citations just as much as politicians love it when economists ply their tools of the trade in support of these politicians’ economic policies. In this regard, Sen. Bernie Sanders is no different than Sen. Marco Rubio, and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton no different than former Gov. Jeb Bush. Yet fact-based, data-driven economic modeling based on the best available evidence often misses the mark due to seemingly obvious missing factors.

Take the still-simmering internecine battle among left-leaning economists over Senator Sanders’ economic policy proposals—which University of Massachusetts Amherst economist Gerald Friedman models, showing that U.S. economic growth would top 5 percent if he becomes president and if he is able to implement his entire platform immediately. Setting aside all of the politically unknowable “ifs” in that last sentence, Friedman’s model tells us that the Sanders growth machine will be powered by a swiftly rising employment rate—the share of the U.S. population with a job—up to 65 percent by 2026, 8 percentage points higher than current forecasts by the Congressional Budget Office. These are big employment gains.

In support of this projection, Friedman argues in footnote 22 of his paper that women’s labor force participation will rise because women’s wages will rise after President Sanders signs into law, implements, and enforces the Paycheck Fairness Act, which would reduce discrimination against women workers. Pay is certainly an important reason that women work, but it’s not the only reason that women stay out of the labor market. Research shows that policies such as paid family and medical leave, stable workplace schedules and scheduling flexibility (that works for workers, not just their employers), and, especially, safe, affordable, and enriching child care and elder care boost women’s employment and that of caregivers more generally.

Generations of economists have failed to put the need for care and the effects of that care provided predominantly by women into their labor supply economic models. I cannot make every economist fix their models, but it’s entirely unrealistic—and unjustifiable—to make assumptions about work and time spent in the workforce that ignore the everyday economic realities facing families. Politicians, however, are starting to get what so many economists have missed. Senator Rubio, Secretary Clinton, and Senator Sanders all have policy platforms that include paid family leave, and Secretary Clinton talks a lot about her plans for expanding access to child care.

These policies have demonstrable effects on employment and earnings. Researchers have shown that California’s paid family leave law has increased leave-taking for mothers and fathers and improved mothers’ employment outcomes. Mothers who have access to this new benefit are more likely to return to work after the birth of a child, and when they return to work, they put in more hours at work compared to mothers who did not use paid leave. These outcomes are supported by the fact that leaves are equally available to men and women; because fathers are using their leave, too, this gives mothers the support they need to address work-life conflict. More striking are the labor supply effects of universal child care policies. After Quebec implemented a universal child care program, for example, researchers found that mothers’ labor force participation rose by 13 percent.

This academic and policymaking attention to the issues of work-life conflict in our economy and our society on the presidential campaign trail follows many successes in implementing new policies at the state and local level. Very recently, Vermont’s legislature passed a bill that Gov. Peter Shumlin has expressed support for, giving workers employed more than 18 hours a week the right to earn up to five paid sick days each year (although only three days in the first two years of the law’s implementation). This is the 28th place in the United States to put such a policy in place, following four other states, 21 cities, one county, and the District of Columbia.

Yet, too often, politicians tend to see work-life policy as just another sop to just another interest group: women. (Never mind that we’re the majority of the population.) This is a big mistake. Economists and policymakers alike need to put women’s participation in the economy and in family life at the center of how our economy grows and works now and over time.

To understand what makes the economy grow, we need to know what hinders people from fully engaging in the labor force. Our nation’s inattention to the causes and consequences of work-life conflict is a serious hurdle for many families. Fixing it will require serious research followed by evidence-based policymaking to change how work is done in our society.

The consequences of higher labor standards in full service restaurants: A comparative case study of San Francisco and the Research Triangle in North Carolina

Overview

Across the United States, policymakers in states and cities are grappling with a groundswell of public support for higher local minimum wages as well as other improvements in labor standards, among them better health care and paid sick leave for employees. In many of these communities the so-called “Fight for $15” movement, led predominantly by fast-food restaurant workers seeking to raise local minimum wages to that level, is spurring policymakers to consider the economic merits and possible adverse effects of such a policy move.

Download Fileinside-monopsony-ib Download this Issue Brief

Overall, most economists agree that moderate increases in the minimum wage do not result in job losses. In fact, boosting the minimum wage may reduce employee turnover—a net positive result for employers who could spend less on hiring and training new workers and enjoy sustained productivity from their employees. Yet economists are less sure how locally-enacted minimum-wage raises and higher labor standards reshape employment practices within individual companies. One way to find out is to compare one community where higher labor standards are in place with one where there are no enhanced standards, focusing on one industry in particular.

Such a comparison is particularly apt in the full service restaurant industry in San Francisco and the Research Triangle communities in and around the cities of Durham, Raleigh, and Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Local labor standards in San Francisco include the nation’s highest minimum wage, a mandate for employee health care, and paid sick leave. In contrast, full service restaurants in Research Triangle communities follow lower federal minimum wage guidelines, including much lower hourly wages for tipped employees ($2.13 per hour), and are not required to provide employee health care or paid sick leave.

This issue brief details the findings of a comprehensive research paper that I presented at the Labor and Employment Relations Association Conference in January of this year. I examine employer responses to higher labor standards through a qualitative case comparison of the full service restaurant industry across these two fundamentally different institutional settings. The results are striking.

In San Francisco, higher labor standards led to greater “wage compression” in specific occupations within the restaurant industry, meaning that employers had less “wiggle room” to offer slightly higher wages to cooks or dishwashers or food servers or bartenders. Concurrent with this wage compression was a rise in professional standards as employers sought to hire and keep already well-trained workers at higher wages and with expanded benefits. Both developments reduced turnover and attracted more professional employees who maintain a high level of customer service.

In the Research Triangle region, the lack of higher labor standards led to a wider distribution of wages across the industry and within individual establishments. Thus employers could differentiate wage levels within job categories to a greater degree. This allows a labor practice that offers low-wages for entry-level employees with little experience but accepts a high rate of turnover as a result. This practice also translates into higher training expenditures for firms. In San Francisco, employers required more experience and professionalism from their new hires.

In both cities, however, a large wage gap remains between front-of-house and back-of-house occupations—a gap that correlates strongly with existing racial and ethnic divisions within restaurants (Latinos in the back; whites in the front). Some employers in San Francisco are addressing this gap by radically restructuring their compensation practices by adding service charges and, in some cases, eliminating tipping. In these restaurants, wages are more balanced across workers, whether they are making food in the kitchen or taking the orders and serving food and drinks to customers.

These findings are important for state and local policymakers to consider. Full service restaurants in the United States added 811,700 jobs nationally between the end of the Great Recession and October 2015, outpacing overall private-sector job growth by nearly 7 percent. What’s more, this trend is expected to continue as jobs in food service occupations are projected to grow faster than the overall labor market through 2030. Thus the restaurant sector is a useful harbinger for the predominant labor market conditions that policymakers can expect going forward—namely the proliferation of low-wage jobs in service industries that can’t be offshored.

Understanding how labor standards affect the pace of job creation and more general aspects of the employment is critical. In the full service restaurant industry in San Francisco, higher labor standards suggest the following results may occur in other cities enacting similar policies:

- Higher professional standards may result in lower employee turnover and more productive workers.

- Lower employee turnover and more productive workers may increase sales for owners and ultimately create better dining experiences for customers through better service.

- Higher professional standards may limit entry-level opportunities within the industry, while lower standards may result in more employer-provided training for new workers.

- Currently large wage gaps based on race and ethnicity between restaurant workers in the kitchen and servers and bartenders interacting directly with customers are not fully resolved by higher labor standards.

- Steps to end tipping in favor of salaried employees in the front and back of restaurants may result in more uniform wages within restaurants, and may result in less ethnic and racial inequality within individual restaurants.

There are, of course, limitations in how much local labor standards can improve the quality of jobs within the restaurant industry. More research is needed to fully assess the impact on overall wage inequality and opportunity structures more generally. But broadly, my research suggests that “high-road” labor standards may well lift wages overall while reducing wage inequality and improving professionalism.

The full service restaurant industry today

The restaurant industry employs more than 10.2 million workers today, of which about 5.3 million are employed in full service restaurants, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The restaurant industry overall epitomizes two trends evident in service industries overall in the United States—relatively high growth alongside low job quality—which is arguably why the sector is facing new demands for minimum wage increases at state and local levels.

The U.S. economy is slowly recovering from the depths of the Great Recession, yet the labor market continues to show weakness even as the unemployment rate has fallen to a below 5 percent. Despite optimistic accounts of the “re-shoring” of manufacturing and a recovering housing market, economic inequality is on the rise. That’s because the majority of jobs created since the end of the recession are relatively low-wage. Indeed, a unique feature of the current recovery is the so called “missing middle” in the pattern of job growth, with relatively few new middle-income positions or career pathways for workers who lack advanced skills. As a result, an increasing number of workers remain in low-wage positions for longer periods of time. Jobs that were once viewed as “stepping-stone” positions, among them restaurant work, are increasingly becoming relatively permanent careers that have little opportunity for long-term wage growth.

Recent research conducted by Restaurant Opportunity Centers United and affiliated scholars provides new evidence on wages, benefits, working conditions, and the extent of racial and ethnic discrimination. In 2011, the organization released a study conducted in eight large metropolitan regions that consisted of surveys and interviews with both employees and employers that documented the prevalence of low wages, lack of access to health benefits and sick leave, and persistent occupational segmentation by race.

More recently, scholars Rosmary Batt and Jae Eun Lee of Cornell University and Tashlin Lakhani of Ohio State University presented results based on a national employer survey across 33 large metropolitan areas focused on variation in human resource practices across restaurant market segments. They find a clear link between higher quality human resource practices and lower turnover. In a related study Batt highlights case studies of restaurants that pursued what she calls “high-road” practices, which include higher relative wages, more full-time work, and more investment in training—all of which resulted in lower employee turnover and improved productivity.

Conditions in the low-wage service sector overall are at a historically low level, with stagnant wages, uncertain working conditions and hours, and a hostile regulatory environment toward organized labor. Given these trends, a central concern for policymakers is what can be done to reduce wage inequality in these growth industries of the future. The impact of publicly mandated labor standards on employment and employee benefits is well studied and continues to be debated among economists and policy makers. But there are important missing pieces in our understanding of how locally enacted labor laws may have deeper consequences. In many ways, the behavior of actual firms remains a “black box” for researchers in the field. Raising labor standard has an affect beyond just the level of, among them changes in the rate of turnover, productivity, training, tenure, and professional expectations and norms.

A tale of full service restaurants in two cities

Using a methods-comparative case design that analyzes employment practices across the restaurant industries in two institutionally divergent urban labor markets—San Francisco, which has the nation’s strongest local labor standards, and North Carolina’s Research Triangle region, which does not—one can discern how higher labor standards affect wages and professionalism in the full service restaurant industry. (See the brief methodology at the end of this issue brief or the LERA website for a link to the full research paper.)

San Francisco employers must pay the nation’s highest minimum wage ($10.74 per hour rising to $15 by 2018), a pay-or-play health care mandate (up to $2.33 per hour) in which either the employer or the city provide employee health insurance, and paid sick leave requirements. In addition, tipped workers must be paid the full minimum wage. In the Research Triangle region of North Carolina there are no locally enacted labor standards. Thus, the effective wage in San Francisco is more than $13.00 per hour. North Carolina, in comparison, follows the federal standards of a $7.25 minimum wage and $2.13 tipped minimum wage, and has no paid sick leave or health care spending mandate.

While the regional labor markets of these two cases differ on a number of dimensions beyond the strength of local labor standards, there are a number of similarities that make this comparison plausible for detecting causal effects of labor standards. First, both regions are home to many high-tech employers and both have comparably tight overall labor markets. Lastly, both cases have a similar number of full service restaurant establishments, resulting in a similarly sized sampling universe.

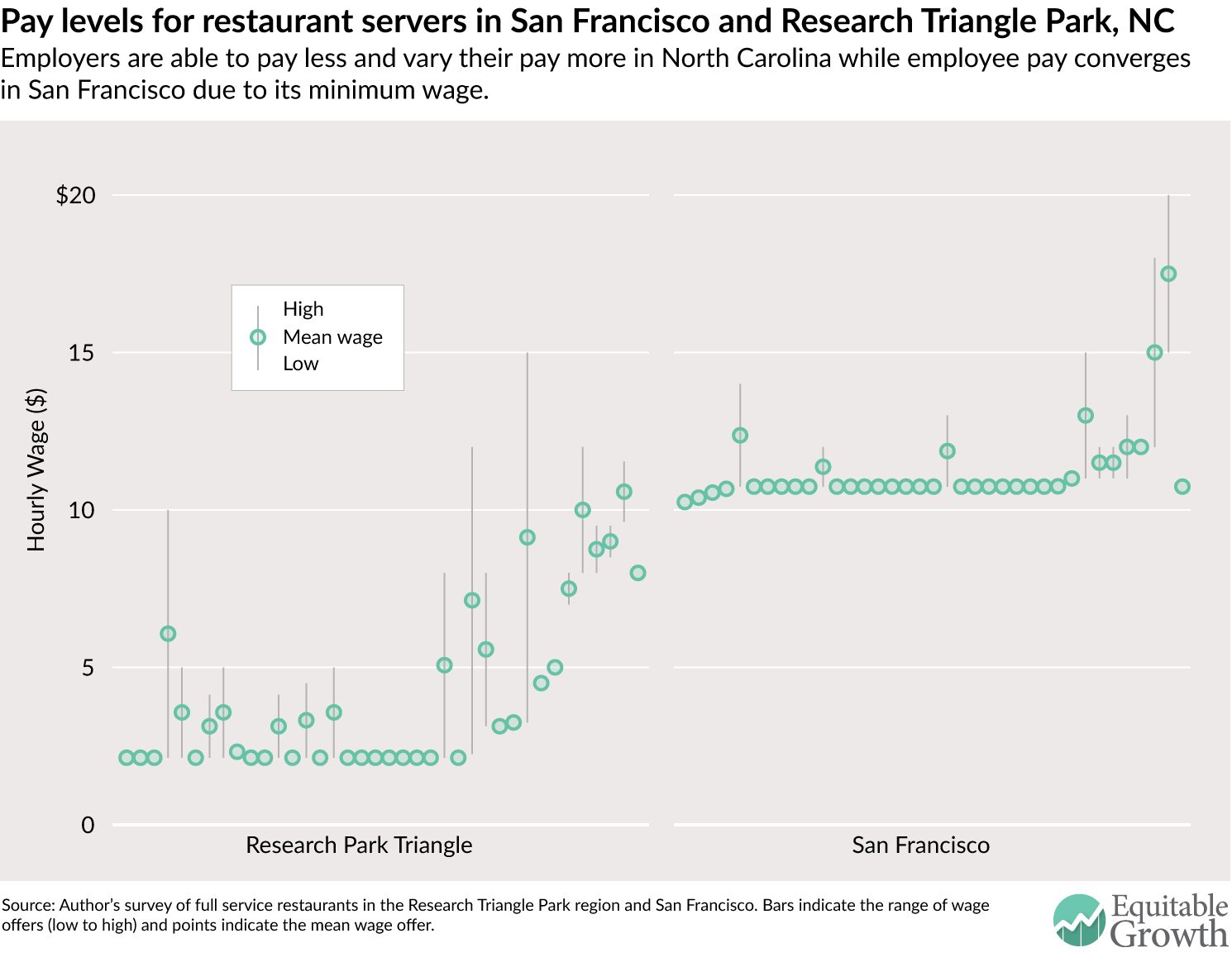

The first finding in my research is perhaps the most telling—San Francisco’s higher minimum wage compared to North Carolina means that the San Francisco restaurants experience less variation in existing wages in different occupations within their establishments and among the establishments themselves. In other words, San Francisco experiences a general convergence of “high road” employer practices compared to the Research Triangle region’s existing “low-road” employer practices. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

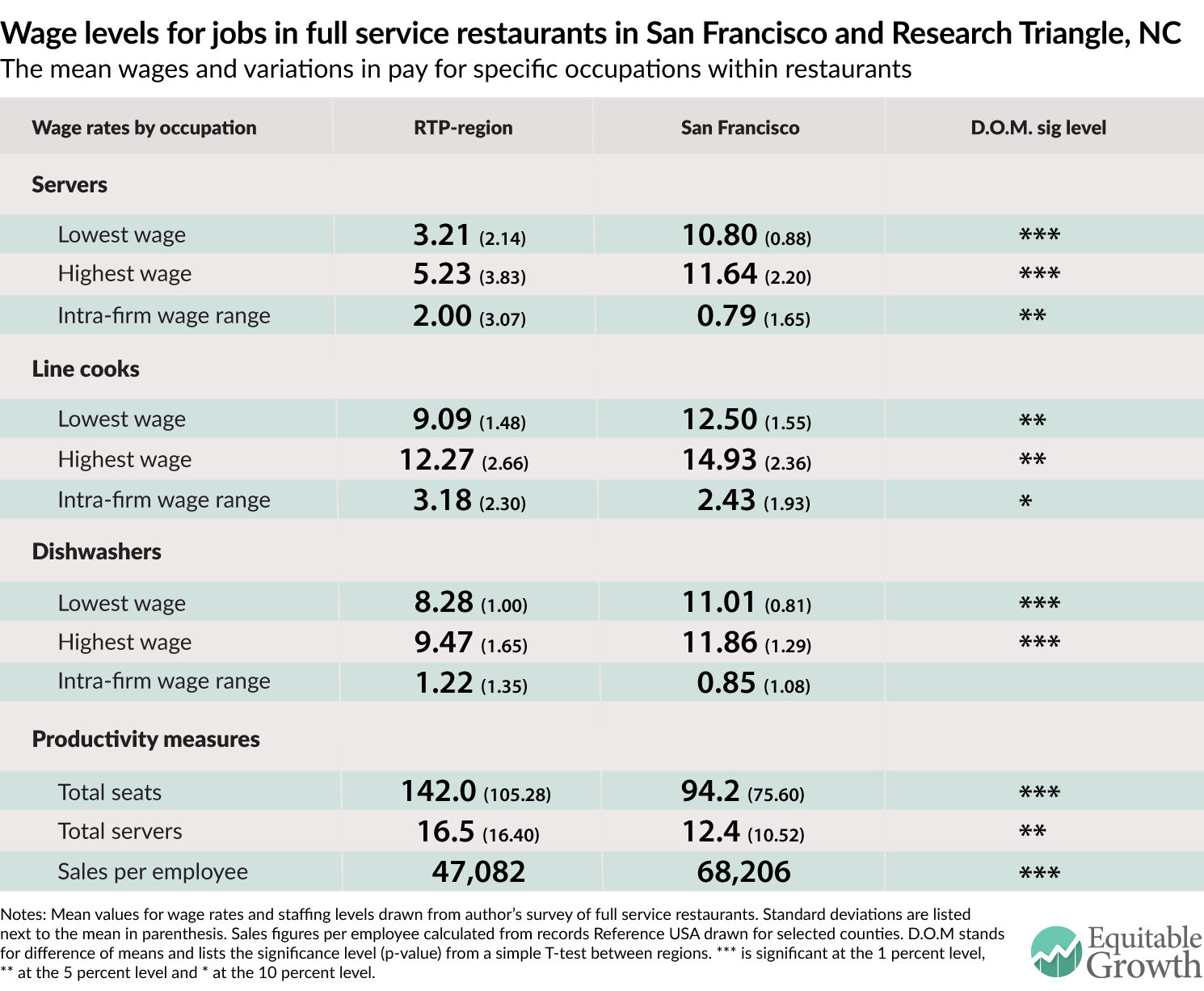

The same pattern is apparent in other jobs within these restaurants in the two cities. Overall, the variation in wages is greater and the wages lower in the Research Triangle region North Carolina compared to San Francisco. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Pushing the High Road Higher in San Francisco

My research also finds that other non-pay related labor standards also had an effect on restaurant labor practices. This is particularly evident in how some employers reacted to the enactment of San Francisco’s pay-or-play health care mandate. Rather than requiring employers to provide insurance directly to workers, the San Francisco Healthy Families Act of 2007 requires employers to pay up to $2.33 per hour worked for each employee. These payments can go either directly to the county health system—where resident workers can receive low-cost care—or into a separate health care spending account set up for each worker. This mandate involves a significant but uniform cost increase for all employers in the industry.

After the passage of this law, some employers decided to spend more than the mandated minimum for their employees’ health insurance in order to provide actual employer-subsidized health insurance to all workers—a benefit that is extremely rare in the industry. As one employer said: “This year for example, we did employee health insurance for everyone…now everyone has real insurance, not just the city thing. We think and hope it will help retain employees.”

Another San Francisco employer echoed the logic of providing full employer-sponsored health insurance rather than simply paying the lower cost option of a per-hour fee to the City. The manager of one neighborhood-based fine dining restaurant explained: “Part of our decision to offer health care goes beyond a simple cost-benefit. What’s another thousand dollars if you already have to spend a certain amount of money. There is a kind of revolutionary like revolt thing happening in that I’m not going to just sign a check over to the city. I’m going to actually give it to my employees. And then the other part is it becomes part of your hiring and your attraction is that you say hey, we offer full benefits.”

This manager’s initial sentiment reflects animosity toward the city government for enacting the Healthy Families law in the first place. Yet the employer’s actual behavior in paying more for full insurance indicates how the labor standard induced the employer to go above the minimum and embrace the potential retention and morale benefits for their workforce.

Beyond direct wage and benefit offers, employers in San Francisco reshaped other aspects of their employment relationship in an effort to differentiate themselves from other employers in the market, and to ultimately retain valued employees. Several interview subjects discussed how they attempted to create a unique work “culture” that is “exciting,” “fun,” or offers indirect benefits to workers, even in cases where employers cannot raise wages beyond the mandated level. One case in point: An owner-manager of a casual neighborhood restaurant allows line cooks to use the resources of the restaurant to further their career development and pursue income-generating work as part-time caterers. Another employer tries to retain key workers in lower-paid occupations through the use of in-kind compensation that is matched to the specific needs of the individual worker—in this case an employee-of-the-month award for back-of-the-house employees in the form of calling cards to reach families back in Mexico.

While these may seem like relatively minor gestures on the part of some employers, these forms of non-wage compensation represent additional ways in which employers try to differentiate themselves in order to retain workers. In the face of strong, binding labor standards that effectively limit the degree to which they can vary wage levels (“taking away the low-road”), employers try to structure their relationship with their workers in other ways. In these two examples we observe restauranteurs who—perhaps implicitly—are adopting some of the same progressive human resource practices typically associated only within high-skill industries or occupations. Specifically, they are recognizing and seeking to accommodate the individual needs of each worker, whether that relates to the worker’s need for outside income through catering or in-kind support of family obligations.

Worker training, retention, and productivity in the two cities

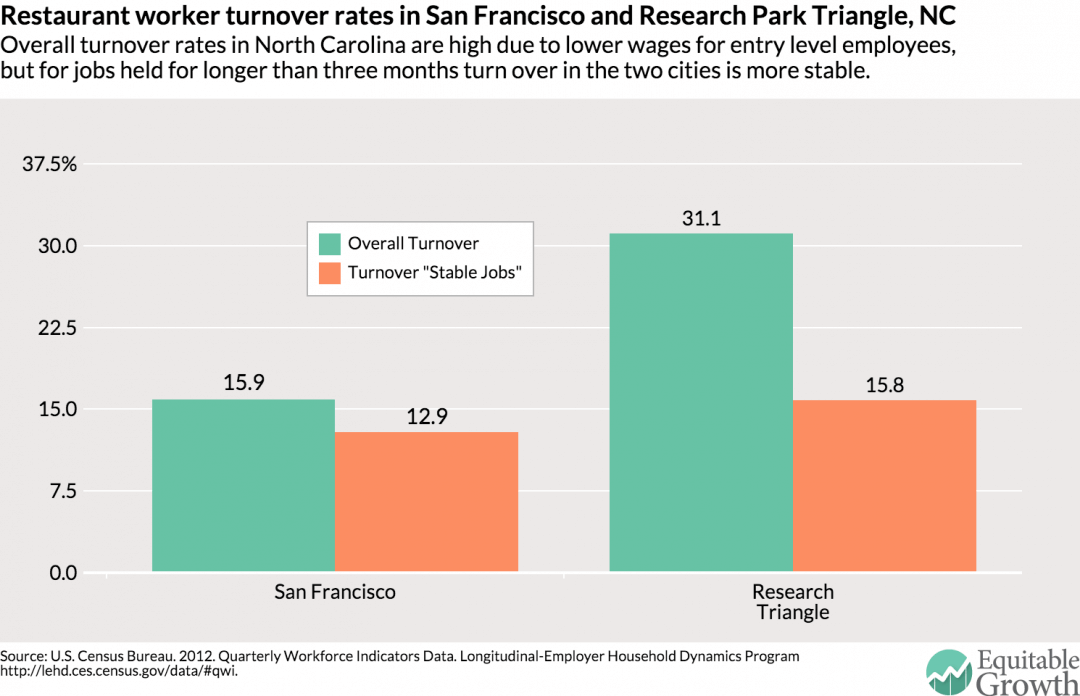

One reason employers need to do worker training in the San Francisco restaurant industry compared to the Research Triangle region is to retain workers. More stable jobs are definitely more in evidence in the city. The rate of turnover for the overall full service restaurant industry in San Francisco was 15.9 percent in 2012, according to official statistics from the Quarterly Workforce Indicators program. This compares to 31.1 percent in the Research Triangle region.

Importantly, however, this stark contrast in turnover is largely due to the relatively high rate of short-term workers who enter and exit employment at a given firm within the same quarter in the two cities. The difference in the turnover rate for “stable” jobs—meaning jobs that last more than one quarter—is much lower (12.9 percent versus 15.8 percent. This means that the full service restaurant sector in the Research Triangle region features a significantly higher number of unsuccessful, or weaker job matches than San Francisco’s restaurant sector. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Those very short term jobs—lasting less than one quarter—are often described by labor economists and other observers as evidence of bad matches between employees and employers. Such high turnover is because workers quit to take a better job, stop working altogether, or were fired. But such high turnover is also indicative of employers operating in labor markets with lower standards hiring workers with weaker expectations of worker quality, which leads to a lower bar for entry level jobs and ultimately more firing of low-quality workers.

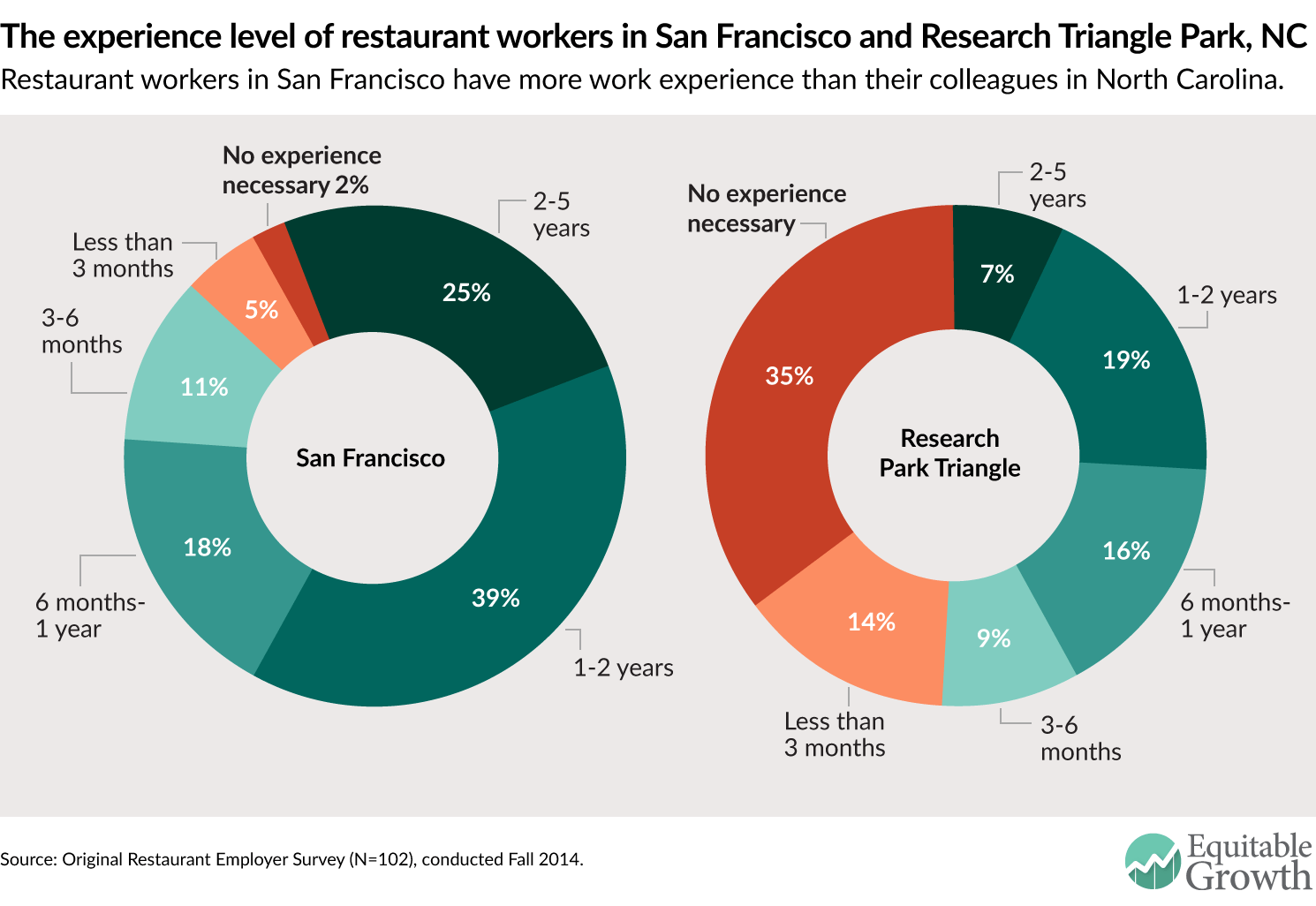

Such differing expectations are evident in the age and education of restaurant workers in in these two cities. The restaurant industry in the Research Triangle region tends to hire younger workers with a lower level of formal education. Specifically, 49.5 percent of workers in there are under age 24 or have less than a high school education, compared to 38.9 percent in San Francisco. Conversely, 40.6 percent of workers in San Francisco have some college or a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 29.7 percent in the Research Triangle Region. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4

In addition to hiring an older and more educated workforce, San Francisco employers generally engage in more careful searches, which lead to overall better matches. First, employers in San Francisco report higher experience requirements for new hires across the occupational spectrum. As seen in Figure 4, only 8 percent of survey respondents in San Francisco reported that new servers could be hired without any previous experience in the restaurant industry, compared to 46 percent in the Research Triangle region. Also, a larger proportion of the San Francisco employers reported experience requirements of over one year—33 percent in San Francisco, compared to 25 percent in North Carolina.

The lower bar for entry into employment is also confirmed in employer interviews. One manager of a neighborhood bistro in Raleigh explained what he looks for in a new front-of-house worker: “Basically, we require [that a server] can work a four-shift minimum per week and go an entire shift, an entire eight-hour shift without smoking a cigarette and [without] any facial piercings or anything. Beyond that, just come in with a smile on your face.”

Even at restaurants in the region that do prefer experienced workers, managers and owners did not articulate how experience matters or which specific skills and industry-specific knowledge they require. As one upscale bar-and-grill manager explained: “We look for at least one year’s experience, but the biggest thing we look for is we look for the person. We don’t look for the skill. I could teach anybody how [to] wait tables [and] pour drinks. I can teach anybody how to cook steaks. What I can’t teach is how to be a good person.”

Employers in San Francisco discussed the minimum level of experience needed to work in front-of-house positions in a distinctly different tone. Rather than viewing servers as essentially interchangeable laborers who can be trained quickly and easily if they possess a modicum of personal hygiene and a friendly personality, employers in San Francisco exhibited a clear description of what a “professional server” was. One mid-scale restaurant employer said of her front-of-house staff: “We have a lot of people who have made it a career and they’re investing in the knowledge of the product and learning their trade or already know their trade because they’ve done it for years.”

Another San Francisco neighborhood bistro owner described the level and nature of experience needed to fill a server position at his restaurant. “Realistically, to work here, I would say [a server needs] five years of experience, because there’s a wine knowledge level that I expect that you really just couldn’t get any other way,” he said. “If you have ten years of experience at Applebee’s, that doesn’t do anything for me.”

Ultimately these responses indicate that employers in San Francisco are looking carefully at each candidates’ resume and approaching the hiring process with a set of expectations about the nature of work, the skills (how to manage a customer’s dining experience rather than just take orders), and industry-specific knowledge needed to perform at a high level. San Francisco employers tend to view their employees—front-of-house more so than back-of-house—as professionals rather than basic labor inputs.

This rise of professional norms—or the exhibited expectations of employers for certain worker traits that are typically associated with highly trained professionals—can also be seen in the unexpected finding on employer-provided training. Some labor market economists argue that “high-road” employers will spend more resources on training while “low-road” employers expect their low-wage workers to quit and because their low-wage workers seem easily replaceable. But at least in the full service restaurant industry just the opposite is true. San Francisco employers reported spending less time offering formal training periods for both front-of-house and back-of-house staff. Instead, they seek out and expect to find workers who already possess a high level of skills in the industry.

In contrast, more employers in the Research Triangle region discussed a recruitment and training model that was more likely to involve formal screening mechanisms for a high volume of applications and a longer, more formal training period for new hires (particularly for front-of-house workers). These training strategies are maintained to deal with the high level of labor turnover and the reliance on relatively less-skilled workers. The manager of a large sports bar-and-grill described the recruitment and training process at his establishment as highly scripted. “We do all of our applications online,” he said. “When people come in, we don’t physically hand them a piece of paper. We hand them a card. It tells them what website to go on. They go ahead and take an assessment. The assessment is scored, and then we get all those almost instantly. This web-based system pulls all the information up on a Manpower Plan, it tells us what they’ve applied for, where they’ve worked. Gives us a resume, and then it gives us a score on the assessment.”

The manager continued to explain that once an employee is hired, they enter into a formal training period that is standardized for each occupation. “Training is a huge investment for us and it is constant,” he said. “Training days depend on the position. Bartending training is ten days and servers require eight days. In the kitchen it’s probably about ten days. Every day they write note cards on all their recipes. But they’ll take a final. When they take their final, their test in the kitchen, they have to know every ingredient, every ounce, and every item, for the entire station. That’s why we require them to write note cards.”

Even at higher-end restaurants, employers in the region have built a human resource system that accepts a high rate of turnover. “We try to stay ahead of the game so that we’re always hiring, we’re always interviewing, but hopefully it’s not desperation hires,” says another manager. “And we try to have a mix of needs like people who need fulltime, who can work lunches and brunches and all of that, to servers who really want very part time so that you can kind of over staff on busy shifts and then there’s always someone that wants to go home. There’s always a student that would like a Saturday night off.”

Training in San Francisco is decidedly different. Employers there stress “professional norms,” which translates into efforts to support continuous skill upgrading and quasi-professional development activities that are integrated into the jobs themselves. One employer described that in addition to limited initial training for servers, the restaurant has designed a system to support ongoing knowledge development. “Sometimes we’ll assign different topics like rum to one person and then they come back and they’re responsible for training everyone else, doing kind of an in service just to keep it interesting, keep them motivated to learn,” he explained. “If they’re having to present it to someone else, they’re going to want to know the product. It’s sort of a team approach, you would use the whole team to train the rest of the team. Next week somebody gets vodka, next week somebody gets some small winery up in Napa. And we don’t just do products, sometimes we’ll do a certain vegetable, they have to find out the history of it.”

Another San Francisco employer explained that the opportunity to learn on the job actually becomes a recruiting and retention tool for his staff. “The attraction of working here is that they get to taste a lot of wines,” he says. “It’s a big wine list. They can kind of flex their wine muscles a little bit and be like kind of like mini-sommeliers on the floor. They don’t hand over all the wine sales decisions to me or someone else. They handle it themselves. We’ve had no turnover for two years.”

The upshot? San Francisco employers seem to be seeking out better trained, more experienced workers and expecting more from them, which in turn leads to greater professionalism in San Francisco establishments. Specifically, employers in San Francisco readily describe their ideal employees in language typically used to describe professionals—meaning workers who have recognizable industry-specific skills, typically work full time, and invest in their own training.

The persistence of ethnic and racial divides in the full service restaurant industry

One persistent pattern in full service restaurants that hasn’t changed because of differing labor standards in the two cities is this—employers still view back-of-house workers (line cooks, prep cooks, dishwashers) in a less formal, more racialized frame. Listen to the manager of a corporate chain restaurant in Chapel Hill who also previously managed several independent restaurants in the region:

“The Latino workforce, these guys know how to work. They’ve been typically cooking in their own kitchens for large extended families. This is how they typically grew up. So it’s not like me cooking for a family of four at my house, or a family of five, or even doing a Thanksgiving dinner for maybe nine people. They’re cooking three meals a day or whatever it is, for their extended family or for many people in the household. I think that’s where a lot of those skills come into it just based on how they grew up. Compared to those workers with formal culinary education, I’ve probably kicked more people out of my kitchen who had a formal education, because they think they know everything now. It’s one of those things where if somebody taught you how to cook eggs right, if somebody taught you how to do certain things right then that’s wonderful, but can you actually get in that kitchen and perform and do multi tasks.”

The stated preference for Latino workers as prep cooks and line cooks undermines the utility of formal credentialing programs and codified skills that can be marketed across firms. The connection between ethnic background and perceived work ethic can lead to an assumption that Latino workers are monolithic and interchangeable. This ultimately limits the opportunities for individual workers to move up the pay scale.

In San Francisco, employers also offered a view of back-of-house workers that emphasized ethnic stereotypes rather than formal skills or credentials. Explained one ethnic restaurant manager in the city:

“You know, a line cook position, I hate to say it, most of them are my people, most of them are Mexican. And you know, you try to stay away from anyone who went to serious cooking school, went to a culinary academy, or has an AA in culinary kitchen skills. Mexicans are just a better quality cook, they really are. I hate to say it. They might not know what sous-vide is, but if you teach them once how to braise something, how to do it correctly, they’ll do it better than the guy who went to school. It’s just innate.”

Equating ethnic status with work ethic or “innate” ability may lower barriers to entry for new workers seeking a back-of-house job, yet the way employers frame skill through an ethnic lens reinforces the barrier between front-of-house and back-of-house workers. This barrier is important not only because it limits access to better paid server positions, but also because as labor standards rise wage differential grows. The barriers between back-of-house and front-of-house occupations is an observation that nearly all respondents in San Francisco brought up in response to direct questions about how they reacted to rising minimum wage and other labor standards. In particular, employers claim that higher labor standards exacerbate the difficulty they have in finding and retaining high quality line cooks and prep workers. In their view, since the mandates require them to give raises across the board, including tipped workers whose total hourly income already exceeds the new mandate, they have less financial flexibility to offer higher wages to non-tipped workers.

One of the more interesting way in which employers in the full service restaurant industry in San Francisco are responding to higher labor standards–and the persistent ethnic and racial divide between the back and front of the house–is through radically restructuring compensation practices. Specifically, some employers are eliminating tipping and applying an across the board service charge of 18 or 20 percent in order to redistribute income between front-of-house and back-of-house positions.

The elimination of tips is a relatively rare business model in the U.S. restaurant sector, but there have been a number of recent, high-profile examples that have accelerated the pace of change. The nationally recognized restauranteur Danny Meyer, who owns several upscale restaurants in New York City (Gramercy Tavern, Union Square Café), announced that all of his New York-based restaurants would go “hospitality included” within a year. Meyer told the New York Times that he specifically cited the need to rebalance the pay scale for kitchen staff after the recent increase in minimum wage for restaurant workers in New York.

Some interview respondents in San Francisco gave unprompted support for this compensation model. Said the manager of multiple fine-dining restaurants in the city:

“If I opened a new restaurant of my own tomorrow, I would 100 percent put everybody on salary. I would charge a flat percentage surcharge, and I would, I’d put everybody on salary. Direct-to-customer employees probably start at $65,000 dollars a year and they cap out at $110,000 and non-direct-to-customer employees probably start at $45,000 and also would likely cap out at $110,000. And you know, they would be eligible for raises annually based on performance, and then two bonus structures a year.”

While the ability to raise prices or add significant surcharges in order to eliminate tipping may be limited to higher priced restaurants–or very profitable establishments–it is clear that rising labor standards in cities like San Francisco and New York are accelerating this trend. But one barrier to a more widespread adoption of this approach is the way payroll taxes are assessed. If a service charge is collected by the employer—rather than the employee in the case of tips—and paid to workers in salary or higher hourly wages, then the employer must pay additional payroll taxes into the unemployment system. Two additional interview subjects cited this added cost as a minor barrier to moving to a tip-less model.

What is most interesting about this recent restructuring of compensation practices is not that it will be immediately adopted throughout the industry, but that it illustrates how alternative business models can be possible, including ones that focus on evening the playing field between front-of-house and back-of-house workers. Such employment practices would reduce wage inequality as well as racial and economic inequality.

—T. William Lester is an Assistant Professor in the Department of City and Regional Planning

at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill

Methodology

The methodology employed in the larger research paper (that this issue brief is based on) consists of a set of semi-structured interviews with approximately 15 employers in each case. The interview subjects were restaurant owners, general managers, or other key staff who have direct control or influence over the firm’s human resource strategy. Subjects were solicited from and represent all major restaurant market segments (e.g. family-style, casual fine dining, and fine dining), offering a range of observations according to price point and revenue. Interview subjects were initially solicited via a web-based survey inquiring about the willingness of survey participants to participate in a 45-minute interview. Additional interview subjects were solicited through phone calls and in-person requests by the investigator and a graduate student researcher during business hours. Subjects were compensated with a $50 gift card for participation. All interviews were recorded on digital media and transcribed for subsequent analysis.

Download FileInside-monopsony Download full working paper

This qualitative data collection is used to analyze how employers actively and uniquely construct their labor market practices in the face of institutional constraints such as wage mandates and prevailing industry norms. The interviews go beyond the survey results and seek to ascertain why a reported practice, such as investments in training, were chosen. In addition to the interviews, a web-based survey was conducted between July 1st and August 31st 2014 and collected a total of 104 valid responses. The survey consisted of 15 questions and was intended to gather detailed information on wage levels by occupation, training provided, skill requirements and educational attainment of workers. In addition the survey gathered background information on each restaurant such as market segment, average entrée price level, and number of seats available.

What are the essential principles of America’s political parties?

What are the essential principles of America’s political parties?

Paul Krugman seeks enlightenment. But I think he looks in the wrong place. He looks in the works of German Charlie from Trier:

: Partisan Classiness: “Many people in the commentariat are utterly committed to the view that the two major parties are mirror images of each other…

…despite vast evidence to the contrary. But until Harry Enten directed me to… Grossman and Hopkins, I hadn’t really registered the extent to which the same assumption of symmetry is often made by political scientists…. Grossman and Hopkins… document the very real differences in the two parties’ structure… in terms of how they work….

The Republican Party is the agent of an ideological movement, while the Democratic Party is best understood as a coalition of social groups.

The next question, which they really don’t answer, is why. And I find myself thinking about Karl Marx…. Marx declares… the three great classes… defined in part by shared economic interests. But he identifies a problem…. The Democratic Party looks kind of like the class system Marx said was wrong, without ever getting around to telling us why. It’s a coalition of teachers’ unions, trial lawyers, birth control advocates, wonkish (not, not ‘monkish’ — down, spell check, down!) economists, etc., often finding common ground but by no means guaranteed to fall in line. The Republican Party, on the other hand, has generally been monolithic, with an orthodoxy nobody dares question. Or at least nobody until you-know-who, which is why the establishment keeps imagining that ‘But he’s not a true conservative!’ can make the nightmare go away.

Better, I think, than German Charlie as a guide is St. Grottlesex Dean:

60-some years ago, Dean Gooderham Acheson laid out his version of how American politics and political economy worked.

Acheson had been at the center of American politics from the progressive era before World War I into the age of Eisenhower. He had been FDR’s ‘s acting Secretary of the Treasury. He had then resigned on principle because he found the New Deal too radical, and based on legal authorities that were too shaky to support such bold actions. He had returned to the FDR administration on the eve of World War II, working for Cordell Hull in the State Department. There he had helped launch the Marshall plan and the cold war. He ended as Harry Truman’s Secretary of State–and, along with his boss George Marshall, the first of what would become many Democratic cabinet members served up by cynical right-wing Republican pundits and politicians themselves engaged in profoundly un-American activities.

In his A Democrat Looks at His Party, Acheson described American politics thus:

- The Republicans are the party of wealth and enterprise–of those who have made or are making it, of those close to the fire. It thus celebrates and is held together by an ideology of opportunity and achievement.

- The Democrats are the party of everybody else–all those left out to varying degrees, all saying: “Hey! What about me?” It is a coalition of left-out interest groups.

- The contestation of, tension between, and alternation of these two parties is, broadly, very healthy.

From the very beginning the Democratic Party has been broadly based… the party of the many… the underdog…. The many… have many interests, many points of view, many purposes to accomplish, and a party which represents them will have their many interests, many points of view, and many purposes also…. The base of all three opponents [Federalist, Whig, and Republican] has been the interest of the economically powerful, of those who manage affairs…. This business base of the Republican Party is stressed not in any spirit of criticism…. It is altogether appropriate that one of the major parties should represent its interests and its points of view. It is stressed because here lies the significant difference between… the single-interest party against the many-interest party, rather than in a supposed division of… conservative… against… liberal….

[…]

The [Democratic] South…. We tend to see men like Watson, Tilman, Vardaman, and Huey Long chiefly in terms of their bellowings about White Supremacy. But if we drain this off–and the if is admittedly of major importance–what we should see is that the mass support of these men was formed by the dispossessed…. The Southern racist belongs to the same political party as the New York supporter of the FERC… [for each] speaks for the dispossessed, whether in his rural or urban form….

A party which represents many interests and is composed of many diverse groups must invariably know that human institutions are made for man… [that] government [is] an instrument to accomplish what needs to be done…. This is not so easy for those who are persuaded that human behavior is governed by [the] immutable laws… expounded in the Social Statics of Herbert Spencer or those in the Das Kapital of Karl Marx…. It was those whose interests were suffering under the impact of new forces who looked to government… to manage the thrust of forces in the interest of human values. Now… this… takes… brains…. so the Democratic Party is hospitable to and attracts intellectuals. It has work for them to do…

What would Acheson say if he were to rewrite his book for today? He would say:

Gradually, between the political end of Nixon in 1974 and the ascent of Gingrich in 1990, the Republican Party transformed itself from the party of those confident who feel they have a lot to gain into the party of those scared who feel that they had something to lose. Whether they fear civil rights that would take their race privilege and assorted economic advantages, feminism that would take their gender privilege and assorted economic advantages, social democracy with its progressive taxes that would eat away at their wealth, new technologies or new people or simply change itself it would in some way disrupt and a road what they had, even if what they had was not much–they all fear, and they all ally together.

The Eisenhower-Acheson-generation Republicans–and also the Hoover-Coolidge-generation Republicans–worshipped at twin altars: that of equality of theoretical opportunity, and that of accomplished wealth which was the due and proper reward of enterprise and hard work. The Gingrich-Trump Republicans fear even equality of theoretical opportunity. The big trouble with America, they feel, on the economic side is that some hungrier, cleverer immigrant or minority member might outcompete you; and on the cultural side is “political correctness”–that there might actually be some social-cultural blowback: that one might be judged a loser for saying racist or sexist things.

In the difference between the party of those who like property and feel that they have everything to gain from enterprise and change and the party of those who like property but fear that they have everything to lose from enterprise and change—that is, I think, the difference between the old Republican Party and the new one, the one that has reached its culmination in our era of Gingrich, and that was the product of the twin curses of Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon.

America can, I think, make good use of a party of enterprise and creative destruction—and of the property wealth that that generates.

But what need does America have for and what use might it make of a party of fear and stasis—and of property wealth that is above all else scared that somebody might take it away.

—

From Dean Acheson (1955), A Democrat Looks at His Party: p. 23 ff:

From the very beginning the Democratic Party has been broadly based… the party of the many… the urban worker; the backwoods merchant and banker; the small farmer… the large landowners of the South, who saw themselves as being milked by the commercial and financial magnates gathered under Hamilton’s banner; the newly arrived immigrants… the party of the underdog…. The many have an important and most relevant characteristic. They have many interests, many points of view, many purposes to accomplish, and a party which represents them will have their many interests, many points of view, and many purposes also. It is this multiplicity of interests which, I submit, is the principal clue in understanding the vitality and endurance of the Democratic Party….

The base of all three opponents [Federalist, Whig, and Republican] has been the interest of the economically powerful, of those who manage affairs…. The economic base and the principal interest of the Republican Party is business…. This business base of the Republican Party is stressed not in any spirit of criticism. The importance of business is an outstanding fact of American life. Its achievements have been phenomenal. It is altogether appropriate that one of the major parties should represent its interests and its points of view. It is stressed because here lies the significant difference between the parties, the single-interest party against the many-interest party, rather than in a supposed division of attitudes… conservative… against… liberal….

[…]

At the end of the [nineteenth] century there was a lesser, but serious, missed opportunity for Democratic leadership in President Cleveland’s failure to grasp the significance of the Populist and labor unrest… and in his cautious and unimaginative approach to economic depression. The unrest… did not spring from a radical movement directed against the established order… or the constitutional system. It grew out of conditions increasingly distressing… on the farms and in the factories. Its purposes were the historic purposes of the Democratic party… to keep opportunity open, opportunity not merely to rise from barefoot boy to President but for people to find in their accustomed environments useful, respected, and satisfying lives…. The conditions and popular response had many points of similarity to those of the 1930s.

Grover Cleveland… followed the right as he saw it… through a conservative and conventional cast of mind. The agitation seemed to him… a threat to law and order…. Coxey’s Army was met with a barrage of injunctions and… the Capitol police…. The Pullman strike was smashed by federal troops who kept the mails moving, the union leaders imprisoned, and the union crushed. And the financial panic was dealt with through the highly orthodox and [highly] compensated assistance of Mr. Morgan.

The underlying causes… were neither understood nor dealt with… an opportunity was missed…. If, to take one of them, the problems arising out of the concentration of industrial ownership had been tackled when they were still malleable and subject to effective treatment, we might have been spared some aches and pains that are still with us.

But with all this, Grover Cleveland holds an honored place…. When the Congress showed signs… of declaring war on Spain, Cleveland put an end to the business for the duration of his administration by saying… that, if the Congress did declare war, he would refuse to direct it as commander in chief….

[…]

[T]he Democratic Party is not an ideological party…. It represents too many interests to be neatly labeled or to be imprisoned…. It has to be pragmatic…. In the Democratic Party run two strong strands–conservatism and pragmatic experimentation…. [T]he difference between our parties has not been and is not between a party of property and one of proletarians, but between a party which centers on the dominant interests of the business community and a party of many interests, including property interests…. They believe in private property and want more and not less of it. This makes for conservatism.

American labor is now known throughout the world for its conservatism…. the whole stress on seniority grows out of this. Pension rights are property interests of impressive value…. [W]hen a particular kind of property descends in the hierarchy of importance, its owners more and more turn for the protection of their interests to the party of many interests. The owners of land–the farmers–are the most crucial…. Small businessmen, also, are apt to find concern for their problems and welfare lost in the party of business on a larger scale….

But perhaps the strongest influence toward conservatism comes from the south, where for historical reasons all interests… are predominantly Democratic…. Southern conservatism is an invaluable asset. It gibes the assurance that all interests and policies are weighed and considered within the party before interparty issues are framed….

The South also faces us with an equal and opposite truth. It is that some of the most radical leaders of modern times have come from the South. We tend to see men like Watson, Tilman, Vardaman, and Huey Long chiefly in terms of their bellowings about White Supremacy. But if we drain this off–and the if is admittedly of major importance–what we should see is that the mass support of these men was formed by the dispossessed. Huey Long’s “share-the-wealth” program was aimed explicitly at the Southern Bourbons….

The tragedy of the South has been that racism has corrupted an otherwise respectable strain of protest and experimentation in the search for economic equality…. For all the apparent contradiction in the fact that the Southern racist belongs to the same political party as the New York supporter of the FERC, the inner logic that holds them together is that each speaks for the dispossessed, whether in his rural or urban form. What enables the Democratic Party to contain both elements is the fact that the party since the Civil War has made the Legislature the special province of the Southern Democrat, and the Executive the special province of the Northern Democrat….

Entwined with the strand of conservatism in the Democratic Party is the strand of empiricism. A party which represents many interests and is composed of many diverse groups must invariably know that human institutions are made for man and not man for institutions…. Such a party conceives of government as an instrument to accomplish what needs to be done….

This is not so easy for those who are persuaded that human behavior is governed by immutable laws, whether they are the laws expounded in the Social Statics of Herbert Spencer or those in the Das Kapital of Karl Marx…. [T]o the Manchester Liberals the Factory Acts ran squarely counter to economic principles and could end only in disaster. The “forgotten man,” in the phrase invented by William Graham Sumner… was the producer whose wealth was tapped by the government to bear the cost of the social programs for those whom Sumner regarded as weak….

In the last century the economically powerful have stood to gain by the doctrine of laissez-faire…. It was those whose interests were suffering under the impact of new forces who looked to government… to manage the thrust of forces in the interest of human values.

Now… this… takes… brains…. so the Democratic Party is hospitable to and attracts intellectuals. It has work for them to do…

Equitable Growth’s new working paper series

Tomorrow, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth will launch its new working paper series. The new series will feature work-in-progress from our grantees, our in-house researchers, and other scholars in our network whose research investigates the relationship between inequality and economic growth.

The inaugural release of working papers includes three excellent papers. The first, by Julien Lafortune and Jesse Rothstein of the University of California, Berkeley, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach of Northwestern University, was funded through our competitive grants program. Lafortune, Rothstein, and Schanzenbach study the effects of school finance reform on the distribution of school spending and on student achievement.

The second paper, by Bill Lester of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, also received support from our grants program. Lester compares labor market outcomes in San Francisco, which has probably the highest level of labor standards in the country, including a high minimum wage, a health insurance requirement, and paid sick days, with outcomes in the Research Triangle area of North Carolina, where standards are much lower.

The final paper, by Arindrajit Dube of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Equitable Growth’s Ben Zipperer, uses new econometric techniques to estimate the effects of higher minimum wages on employment.

As with all working papers, the research reported here is not yet complete. We hope that the publication of this work-in-progress will promote broader discussion of the issues studied as well as generate feedback that will be useful as researchers prepare their work for final publication.

The forthcoming-behavioral-economics of abundance

: Economics in the Age of Abundance: BERKELEY – Until very recently, the biggest economic challenge facing mankind was making sure there was enough to eat.

From immediately after the dawn of agriculture until well into the Industrial Age, by far the most common human condition was what nutritionists and public-health experts would describe as severe and damaging nutritional biomedical stress.

Some 250 years ago, Georgian England was the richest society that had ever existed, and yet food shortages still afflicted large segments of the population. Adolescents sent to sea by the Marine Society to be officer’s servants were half a foot (15 centimeters) shorter than the sons of the gentry whose heights were recorded as they entered the army as officers. 150 years ago the working class of the United States–the richest working class that was then or ever had been–was still spending roughly 2/5 of extra income at the margin simply on more calories. Pre-Industrial Agrarian-Age human populations, even Mid-Industrial populations, and a third of the world today were and are under what nutritionists and public-health experts see as severe and damaging nutritional biomedical stress.

Inside the bubble of today’s prosperous middle-class North Atlantic, however, things are now different. Perhaps 1% of America’s labor force grows needed calories and essential nutrients. Perhaps 1% transports and distributes the needed calories and essential nutrients. That does not account for the entire food industry, of course. But most of what is being done by the remaining 14% of the labor force dedicated to delivering food to our mouths involves making what we eat tastier or more convenient – jobs that are more about entertainment or art than about necessity.

The challenges we face are now those of abundance. Indeed, when it comes to workers dedicated to our diets, we can add some of the 4% of the labor force who, working as nurses, pharmacists, and educators, help us solve problems resulting from having consumed too many calories or the wrong kinds of nutrients.

More than 20 years ago, Alan Greenspan, then-Chair of the US Federal Reserve, started pointing out that GDP growth in the US was becoming less driven by consumers trying to acquire more stuff. We were no longer in the business of growing economically by arranging more atoms in patterns we found luxurious, convenient, or necessary. Those of us in the prosperous middle class, at least, were becoming much more interested in communicating, seeking out information, and trying to acquire the right stuff to allow them to live their lives as they wished.

Of course, for the rest of the world this is simply not so. The rest of the world still faces dire problems of scarcity. Roughly one-third of the world’s population still struggles daily to get enough food. And there is no guarantee that those problems will solve themselves. It is worth recalling that a little over 150 years ago, both Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill believed that India and Britain would converge economically in no more than three generations.

There is no shortage of problems to worry about: the destructive power of our nuclear weapons, the pig-headed nature of our politics, the potentially enormous social disruptions that will be caused by climate change. But the number one priority for economists – indeed, for humankind – is finding ways to spur equitable economic growth.

But it is not too early to think about this job number two. This job number two–developing economic theories to guide societies in an age of abundance–is no less complicated. Some of the problems that are likely to emerge are already becoming obvious. Today, many people derive their self-esteem from their jobs. As labor becomes a less important part of the economy, and working-age men, in particular, become a smaller proportion of the workforce, problems related to social inclusion are bound to become both more chronic and more acute.

Such a trend could have consequences extending far beyond the personal or the emotional, creating a population that is, to borrow a phrase from the Nobel-laureate economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller, easily phished for phools. In other words, they will be targeted by those who do not have their wellbeing as their primary goal – scammers like Bernie Madoff, corporate interests like McDonalds or tobacco companies, the guru of the month, or cash-strapped governments running exploitative lotteries.

This is a very, very different economics from that of creating Adam Smith system of natural liberty where it can be created and building institutions to approximate its effects where it cannot. The central challenge will be to help people protect themselves from manipulation. And it is not clear that those who currently call themselves “economists” have a comparative advantage in building it–although Thaler, Shiller, Akerlof, Rabin, it seems like half my colleagues here at Berkeley, and many others are certainly giving outsiders a run for their money. But we are starting to lead this different economics–this behavioral economics–with some urgency now. And unless things truly go to hell in a handbasket, the urgency will only grow

Over at Project Syndicate: “Pragmatism or Perdition”

Over at Project Syndicate: Pragmatism or Perdition: BERKELEY – It is almost impossible to assess the progress of the United States economy over the past four decades without feeling disappointed. From the perspective of the typical American, nearly one-third of the country’s productive potential has been thrown away on spending that adds nothing to real wealth or destroyed by the 2008 financial crisis. Since the mid-1970s, the US has ramped up spending on health-care administration by about 4% of GDP and increased expenditure on overtreatment by about 2% of GDP. Countries like Canada, the United Kingdom, and France have not followed suit, and yet they do just as well – if not better – at ensuring that their citizens stay healthy. Meanwhile, over the same period, the US has redirected spending away from education, public infrastructure, and manufacturing toward providing incentives for the rich… READ MOAR

Must-reads: February 29, 2016

- : Inequality Harms Economic Growth for the Poor

- : Who is right on US financial reform? Sanders, Clinton, or the Republicans?

- : School Finance Reform and the Distribution of Student Achievement

- **: Watch five years of oil drilling collapse in seconds

- : Keynes’s Early Work on Monetary Policy

- : Fiscal Policy Success Is All About Monetary Policy

- (2013): How much could we expect the Oregon Medicaid study to reduce blood pressure?

- (2013): How much could we expect the Oregon Medicaid study to reduce blood pressure? – ctd

- (2013): For economist/biostats geeks – ctd x2 (with intro for non-geeks)

- : Updated power calculation

- (2013): More Medicaid study power calculations (our rejected NEJM letter)

- (2013): The Oregon Experiment, Irrationality, and Universal Coverage

- : MIT: Crashes, Terrorists & Sharks, Oh, My!

- : Closing the Investment Gap

- : Fed Doves Still Have The Upper Hand For March

- : This video shows what Ancient Rome actually looked like