This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

Equitable Growth launched our working paper series this week, which will feature research by our grantees, our in-house researchers, and other researchers in our network. The first three papers cover school finance reform, labor standards in the restaurant industry, and econometric techniques.

There’s a still-simmering debate among left-leaning economists about the potential impact of Sen. Bernie Sanders’ economic plan. But as Heather Boushey points out, researchers and policymakers shouldn’t ignore the important role of policy that focuses on supporting care and work-life balance.

Extending the duration of unemployment insurance benefits during a recession increases the unemployment rate. But looking at studies that only consider the first step of the process misses something important: Less job searching can help more unemployed workers find jobs.

U.S. business investment is weak. Productivity growth is slow. Our companies are less dynamic than in the past. All of these trends are intertwined and in ways that researchers and policymakers don’t quite understand. If we care about economic growth, we need to pay more attention to these trends.

Links from around the web

Economists and policymakers are concerned with the drop-off in the rate at which new businesses are being started. But not all startups are created equal. Ben Casselman highlights new research showing that ambitious startups are growing slower than in the past. [fivethirtyeight]

How do we accelerate economic growth? Well, it depends on the timeframe over which you want to boost growth. Dietz Vollrath discusses how policies that focus on aggregate demand work for the short term, and the long term is the provenance of supply-side reforms. [growth economics]

Poverty and housing policy are inextricably linked. Emily Badger highlights a new book by sociologist Matthew Desmond on eviction in U.S. cities, which explores how the rental housing market helps perpetuate U.S. urban poverty. [wonkblog]

A new study shows that a large portion of financial advisers in the United States have histories of “misconduct.” And these brokers and advisers seem to be concentrated in certain firms and certain areas of the country. Matthew C. Klein takes a deeper look at the research. [ft alphaville]

The presidential election season is a time for hearing plans about how the federal government can improve the country. Presidential administrations can make tremendous differences, but some areas are outside of their control, such as housing supply. Derek Thompson argues for the importance of housing constraints. [the atlantic]

Friday figure

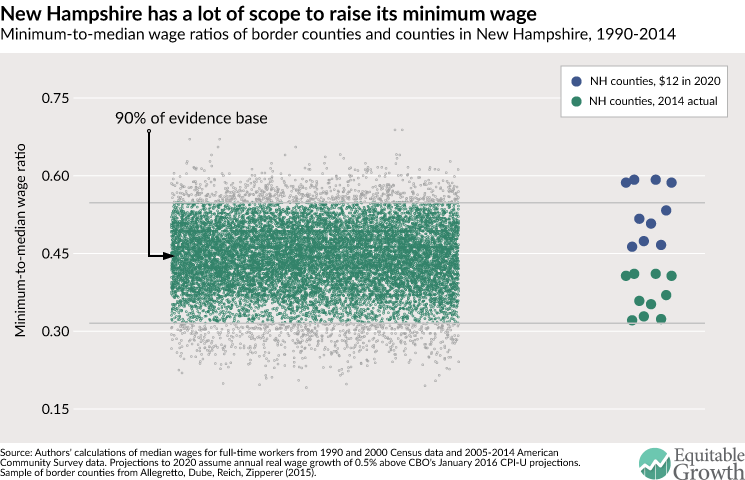

Figure from “History shows why New Hampshire has room for higher minimum wages” by Ben Zipperer.