Must-Read: : The Forgotten State: “Where Levin sees the government crowding out more worthwhile enterprises…

…Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson argue in American Amnesia that the state is central to the success of our economy. In fact, it is impossible to separate them, and you wouldn’t want to anyway. Recovering a phrase that had gone out of fashion, Hacker and Pierson use the term ‘mixed economy’ to describe a set of practices and functions designed ‘to overcome failure of the market and to translate economic growth into broad advances in human well-being—from better health and education to greater knowledge and opportunity.’ It is this mixed economy, the authors contend, that made the United States rich and built the middle class.

Many, even on the left, have come to see the government as a giant redistribution machine. Taxes are collected on one side; income support and social insurance go out the other. But this impoverished view of the state reflects just one function of government, and Hacker and Pierson are out to reclaim the role of the state in the market economy through its role in fixing market failures, advancing science, safeguarding markets, and ensuring ‘that economic gains bec[o]me social gains.’

There is a lot of history to unpack. Since the federal government was founded, it has taken the lead in internal development, monetary policy, corporate chartering, bankruptcy law, land grants, communications law, regulation, public education, and other arenas of major economic importance. The federal government has also been a major agent in reducing incidence of communicable disease, a problem that peaked even amid the economic gains of the late nineteenth century. Not just wealth but public action was needed. Cleaner water and better infrastructure rapidly extended lifespans. Reviving this long story of the role of the federal government has been a major achievement of recent historiography, and American Amnesia puts it on display.

By focusing on the many federal activities taken for granted, Hacker and Pierson show the holes underlying libertarian logic. Milton Friedman famously saw the power of free markets at work in a single lead pencil. No one person knows how to make it, he said. Instead the magic of prices coordinates the action of people in diverse industries around the world. But while Friedman may have been right about the coordinating effect of prices, he ignored the deep network of education, infrastructure, property rights, corporate charters, and other government-enforced legal structures that make private enterprise possible. In a telling illustration, Hacker and Pierson draw on Mariana Mazzucato’s The Entrepreneurial State (2011), which shows how smartphone components—GPS, advanced batteries, cellular technology, touch-screen and LCD displays—were built on a foundation of research that was not just publicly funded but sometimes carried out by the government itself…

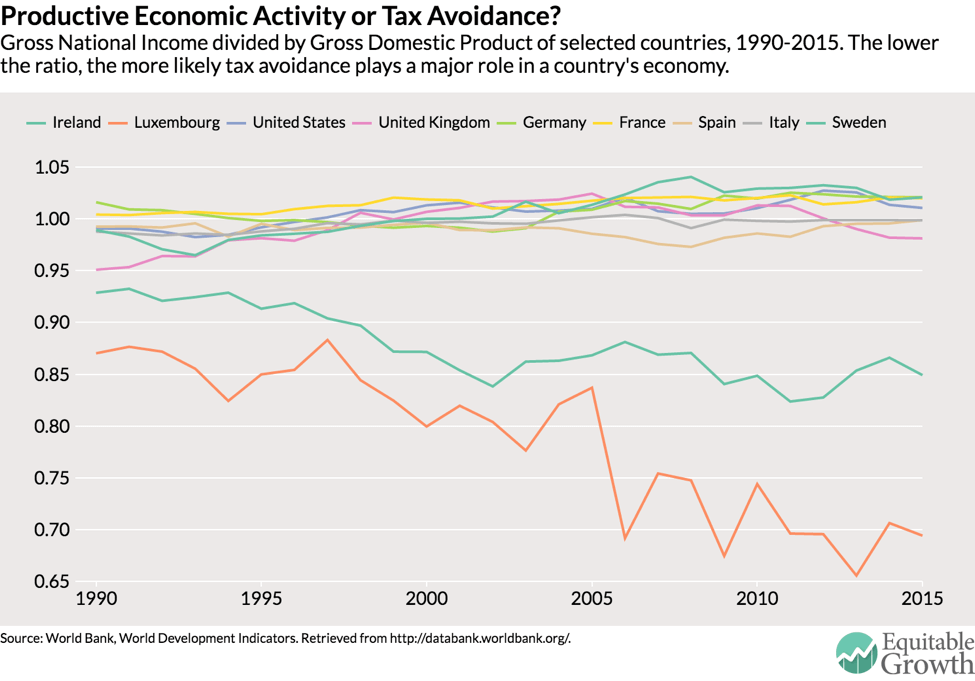

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth today will be hosting a workshop with some of the world’s top scholars engaged in developing a system of distributional national accounts, or DINA. This new approach seeks to incorporate measures of economic inequality into existing calculations of gross domestic product and related components of our national income and product accounts.

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth today will be hosting a workshop with some of the world’s top scholars engaged in developing a system of distributional national accounts, or DINA. This new approach seeks to incorporate measures of economic inequality into existing calculations of gross domestic product and related components of our national income and product accounts.