New research shows paid leave increases mothers’ labor force participation following childbirth

Despite women’s rising U.S. labor force participation over the past seven decades, women remain more likely than men to take time off work and modify their work schedules following the birth of a child. For some women, a break from work around childbirth is a temporary period of recovery and bonding before resuming their previous work responsibilities. For others, however, it constitutes a more significant shift away from the workforce to focus on caregiving.

Whether a new mother fully detaches from the labor force at the point of birth—by quitting her job or being fired without pursuing further employment—may determine whether such a break from work is temporary or more long term. That determination about if or when to return to work after childbirth is dependent on a host of personal and economic factors, such as the degree to which a new mother can rely on other adults to provide care, the care needs of her child, her career goals, and her employer’s flexibility.

But one additional factor may be the perceived cost of exiting the labor force, as measured by changes in her family’s expected income after childbirth. Without paid leave, a new mother may opt for a period of unpaid time off during which she and her family could become accustomed to reduced income. Once a family’s household budget has absorbed this reduced income, the perceived cost of staying out of the workforce is likewise reduced. So, when the new mother determines that there is not a pressing financial need, she may delay a return to the workforce indefinitely to focus on childcare.

Access to paid family leave could affect this calculation of the costs and benefits of detaching from the workforce. By providing partial wage replacement during the time at home caring for a new child, paid leave could prevent families from becoming accustomed to the mother’s lack of income, thereby preserving the “cost” of a change in labor market participation. Indeed, when paid family leave is accessible, it facilitates a return to work for some women when they might otherwise remain at home. That is the central finding of a new working paper by economists Kelly Jones and Britni Wilcher of American University, which examines the long-term effects of motherhood on labor force participation in two states with guaranteed paid family leave: California and New Jersey.

The United States remains the only industrialized nation without guaranteed paid family and medical leave, but eight states and the District of Columbia have enacted their own paid leave systems. The first two states to adopt these policies were California in 2004 and New Jersey in 2009. Early research from these states suggest the programs can increase labor force attachment for mothers in the months of leave-taking surrounding childbirth. Few papers to date have examined this effect over the longer term.

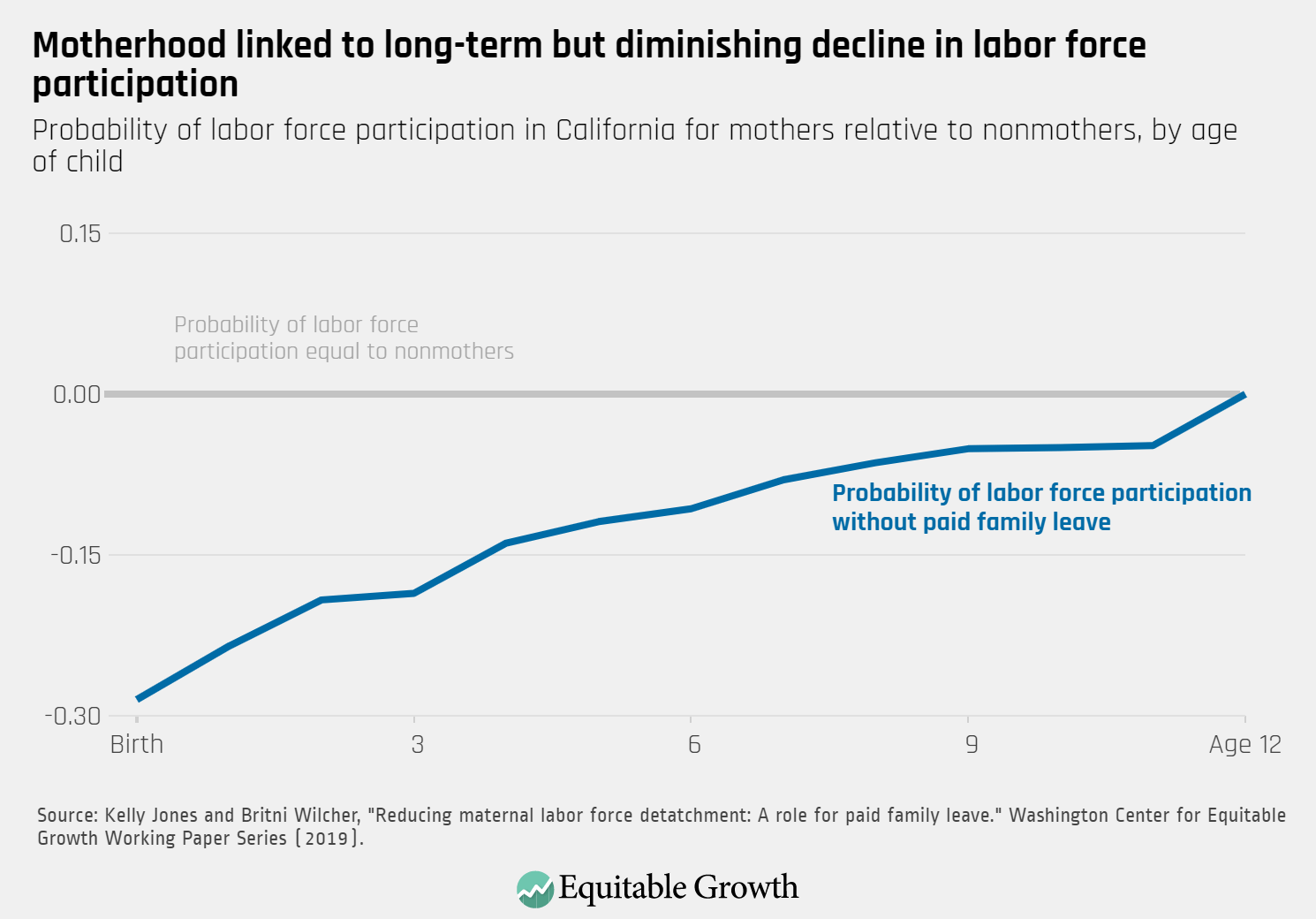

Using data from the Basic Monthly Sample of the Current Population Survey, Jones and Wilcher employ an “event-study difference-in-differences” model to compare the labor market participation of new mothers and women without minor children surrounding the implementation of paid family and medical leave. Their findings indicate that, in the absence of paid leave, motherhood is associated with a significant reduction in the probability of labor force participation in the year of a child’s birth and beyond. The authors found no such reduction for new fathers.

In California, for example, this reduction attenuates over time but remains significant up to 11 years following childbirth, after which point the probability of labor force participation for mothers with young children is no longer significantly different from that of women without minor children. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In other words, a mother with a 10-year-old child is more likely to participate in the workforce when compared to a mother of a toddler, but both women are less likely to participate when compared to a woman without a child at home.

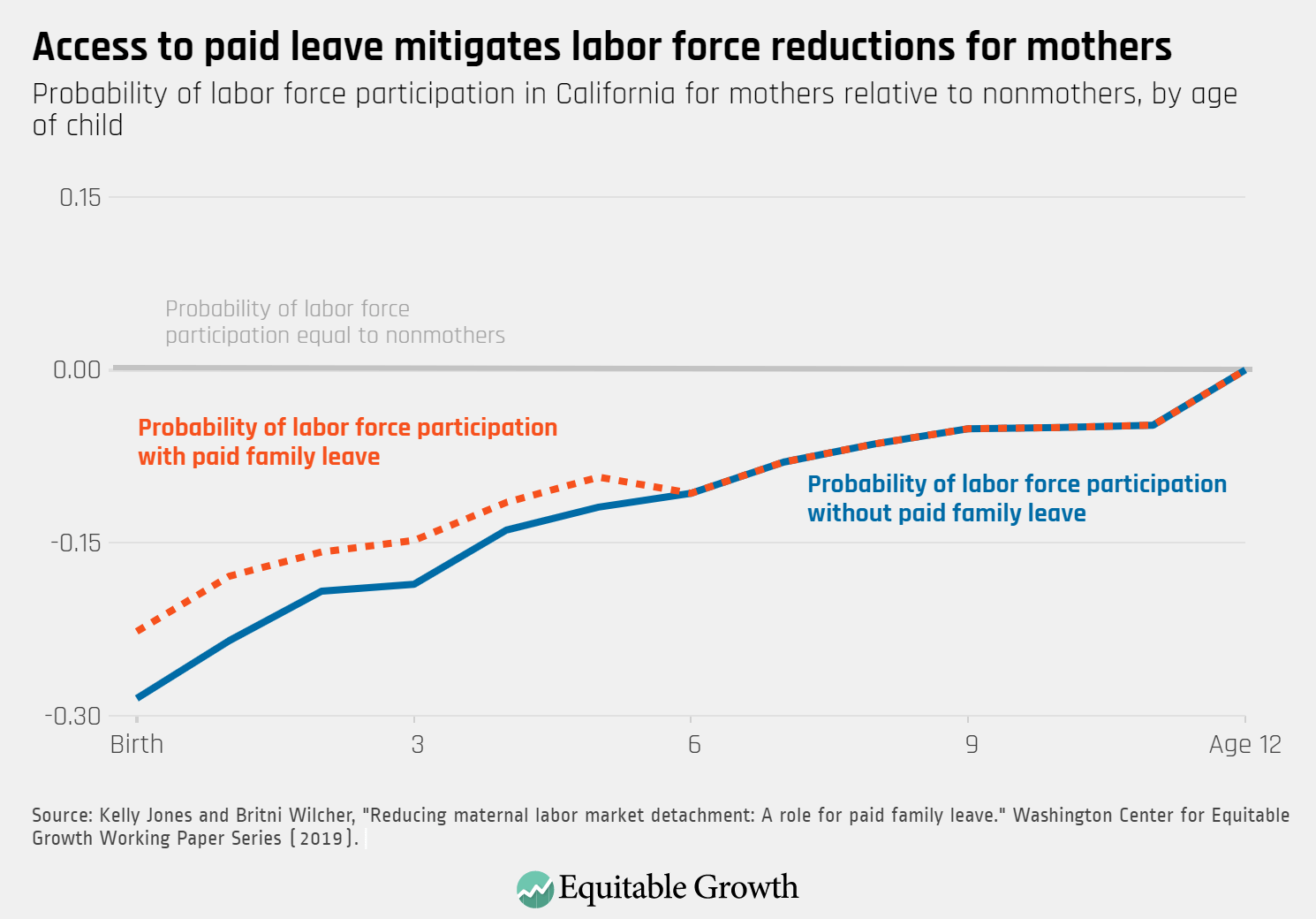

In contrast, the probability of labor force participation for new mothers after California implemented paid leave in 2004 is significantly increased when compared to women who gave birth prior to the policy. More specifically, mothers with access to paid leave in the state demonstrate an approximately 20 percent increase in this probability during the year of their child’s birth. This increase remains significant up to 5 years later, suggesting that the availability of state-provided paid family and medical leave can increase labor force participation well beyond the period of initial leave-taking. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The authors identified similar, though more varied, effects in New Jersey. While data limitations preclude the two scholars from following individual women over time, their findings highlight how paid family leave, or the lack thereof, might have a ripple effect on women’s labor force participation in the United States beyond the months surrounding childbirth.

New mothers who detach from the labor force around a birth face several barriers in returning to the job market. Job-specific skills may be lost. Preferences around work may shift with the addition of a new child. And employers may engage in hiring discrimination against new mothers. These factors may make it challenging to find a new job and could discourage a return to the labor market for month or even years. If paid family leave is indeed a factor in preserving a new mother’s connection to the workforce, then it can mitigate these barriers and facilitate a quicker return to work.

This new working paper contributes to mounting evidence that access to paid family and medical leave can improve both labor market outcomes for women and families’ well-being. It also adds to a subset of research around the effects of paid leave on more disadvantaged families. When disaggregating their results by mothers’ race and ethnicity and education level, Jones and Wilcher find that the benefits of paid leave were more pronounced and longer lasting for white, highly educated women in California and New Jersey’s labor market.

There are two potential explanations for why more disadvantaged families are not seeing the same benefits of paid family leave. First, for lower-income families, parental leave may be a luxury that they cannot afford even with paid leave’s wage replacement. In California, a minimum wage worker in 2004 (the year paid family and medical leave was implemented) earned $6.75 an hour, or $270 after a 40-hour workweek. At a 55 percent wage-replacement rate, paid leave would provide these workers with less than $150 of income a week—an amount that is probably too low to incentivize leave-taking.

In short, these lower-paid workers and their families will forgo parental leave, whether paid or unpaid, and any associated labor market outcomes altogether. Instead, these mothers could be returning to work after only a minimal recovery period. A 2012 Department of Labor survey indicates that as many as 1 in 4 women return to work within just two weeks of giving birth.

A second alternative but related explanation may be that lower-income women are indeed participating in parental leave, but their labor force participation is such that there isn’t much room for improvement when paid leave is made accessible. The authors’ data on less-educated women and women of color suggests that some disadvantaged women are already returning to work faster than their more advantaged counterparts in the years following childbirth, probably because their families are more dependent on the income they provide. When this occurs, any return-to-work effects of paid family leave will be more muted.

For these lower-income families, then, labor force participation is not the best measurement of paid leave’s potential benefits, which could instead manifest as greater financial security or improvements in mothers’ mental health.

Taken together, the findings from this new working paper by Jones and Wilcher point to the importance of providing new mothers with access to paid leave and ensuring that such programs are designed to assist all types of families. Research on paid leave programs highlight the importance of thoughtful programmatic design in order to maximize the benefit for working families. Early program evaluations, for example, confirm that California’s initial wage-replacement rate of 55 percent was indeed too low for lower-income families to participate in the program. The state has since adopted a more progressive wage-replacement structure, providing low-income workers with 70 percent of their income while on leave.

This new working paper comes at a critical time, as more states prepare to implement their own paid leave programs and the U.S. Congress is considering legislation, such as the FAMILY Act, that could produce a national paid leave guarantee for all new parents and caregivers. Jones and Wilcher’s work adds to the expanding, though nuanced, evidence base suggesting that paid leave strengthens women’s labor market attachment and contributes to a stronger economy. Policymakers should consider these findings carefully as they debate national paid leave options and their potential to strengthen the relationship between new parents and the labor force.