New research shows California Paid Family Leave reduces poverty

The United States remains the only industrialized nation without a national paid leave program, despite evidence that these programs can benefit working parents and employers as well. In 2004, California became the first state to establish a publicly funded program for family leave. Eight states and the District of Columbia have since followed suit, and many private-sector employers offer their own paid leave programs, yet the vast majority of people in the United States today—including mothers with new children—do not have access to time off with pay during times of medical and caregiving need.

This broad lack of access to paid leave—and lack of access to leave for new mothers specifically—is in part because most family leave programs remain business-run, and therefore disproportionately benefit families with earners who have high education levels and wages. But there is promise for public programs to assist mothers who are left behind by private leave programs: Recent research concludes that between 2004 and 2013, the California Paid Family Leave program provided important support to mothers at the bottom of the income distribution who usually lack employer-provided leave.

Today, California’s paid leave program, CA-PFL, allows for six weeks of leave for workers who earned $300 in the previous year and have new children or sick family members, as well as up to 52 weeks for personal medical needs. It provides most claimants with 60 percent of their full-time wages, with a 70 percent level for low-income claimants, and job protection for workers in businesses with 20 or more employees. Approximately 50 percent of eligible new mothers made claims in 2017, and they were able to combine six weeks of caregiving leave with six weeks of medical leave, for a total of 12 weeks of leave.

Between 2004 and 2013, an older law was on the books and the program was both less generous and less used. During that time, the program provided only 55 percent of claimants’ previous full-time wages, but they were not guaranteed job security. The initial take-up rate was lower than today, with only 40 percent of eligible mothers making claims in 2004.

This earlier period is useful to study because data collected in this period reflects a paid leave program operating in a context in which claimants don’t need high levels of earnings to qualify, but they lack job protection. This data is ripe for exploring the question of how a paid leave program with these features affects the economic security of families.

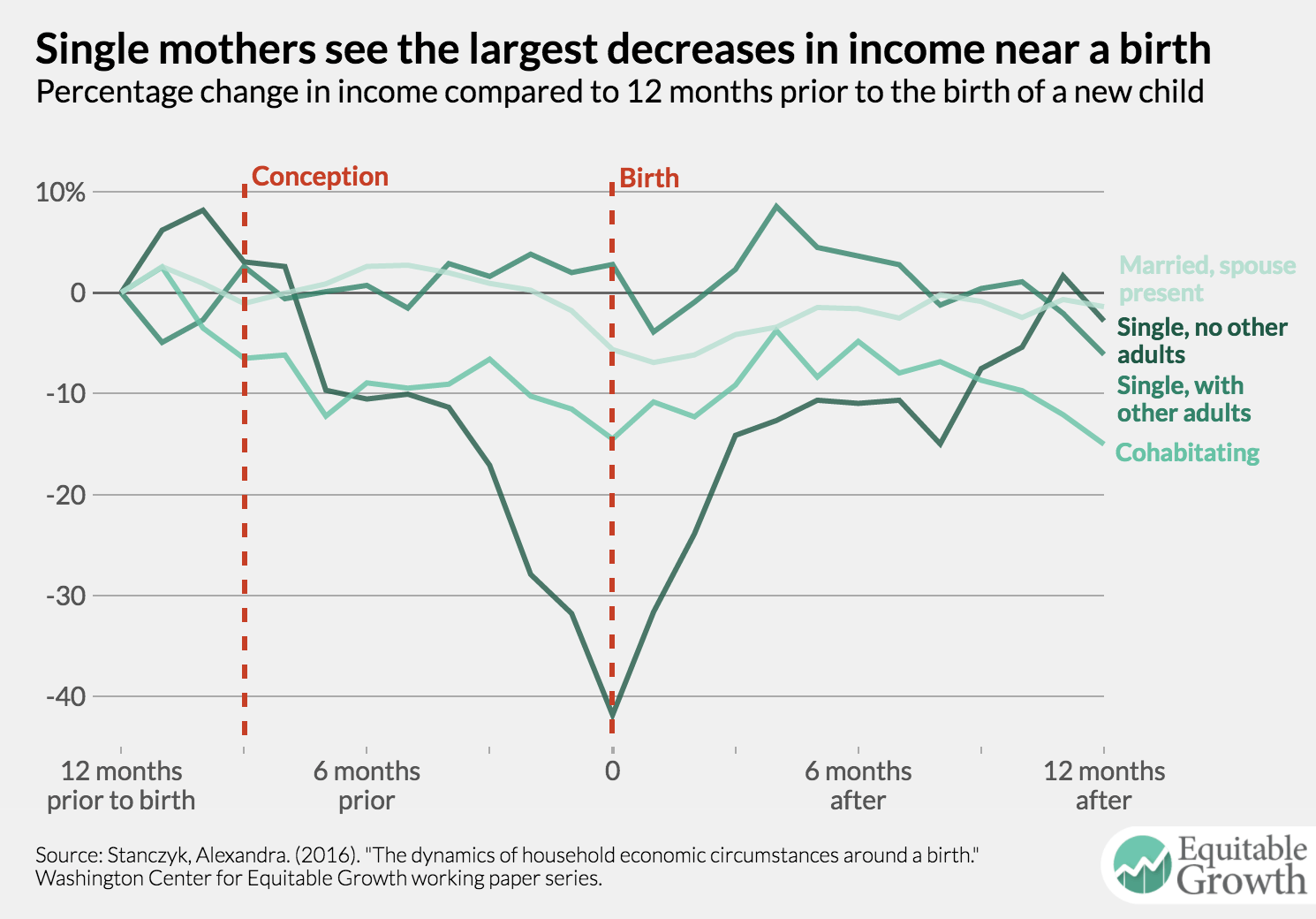

In a paper recently published in Social Service Review, Alexandra Stanczyk—a researcher at Mathematica—explores just that. She assesses whether the California Paid Family Leave program improved household economic security for families directly following the birth of a new child. Since the changes associated with the birth of a child can strain a family’s economic security, this is a particularly important time to provide an economic boost to families. This line of inquiry connects to a larger question, about partial wage-replacement programs, that informs the federal policy conversation around paid leave: Does partial wage replacement actually improve a family’s economic security?

From one perspective, partial wage replacement could improve the economic security of a family by providing a subsidy for leave that would have otherwise been unpaid. This increase in household income could improve the long-term stability of a family’s finances and ease much of the tension created by the financial burden of a new child.

Alternatively, if workers who would have otherwise returned to work earlier take a longer leave period than they would have had they not had access to paid leave, then these program participants receive only half of their wages when they would have otherwise received full pay. This could lead to an overall decrease in a family’s annual household income. The lack of job protection during the study period also could negatively impact the labor force participation of mothers if employers lay off mothers who take up paid leave. Both mothers’ extended leaves and lay-offs could push low-income families across the poverty threshold.

Using American Community Survey data from 2000–2013, Stanczyk used a model that social scientists refer to as a “triple-difference model” because it draws three comparisons. Stanczyk looked at California mothers of 1-year-olds, compared to California mothers of older children and compared to mothers in other states, both before and after the state’s CA-PFL law was passed in 2004. She examined both poverty rates and household income of these mothers.

Stanczyk finds that between 2004 and 2013, the California paid leave program increased household income levels and lowered poverty rates for mothers of 1-year-olds.

First, she found that the program fosters an average $3,407 increase in income for mothers of 1-year-olds. These big effects, however, could reflect changes at the top end of the earnings distribution because they are average effects and could capture big earnings gains for people who were earning at high levels prior to giving birth. But in additional analyses, Stanczyk also finds good news specific to the bottom end of the income distribution: The introduction of paid leave in California is tied to a 10.2 percent decrease in risk of new mothers dropping below the poverty threshold and disproportionately helps women with lower levels of education and who are unmarried.

According to a study conducted by the Pew Research Center, U.S. adults overwhelmingly support national paid family leave, with 85 percent saying that workers should receive paid personal medical leave and 82 percent approving of paid leave for new mothers. The U.S. Congress is accordingly engaged in discussions about bipartisan legislation to institute a national paid family leave program. Within the past six months, there have been multiple bills for expanding paid leave introduced by each party, among them the Paid Family Leave Pilot Extension Act, the Working Families Flexibility Act of 2019, and the Federal Employee Paid Leave Act.

The 2019 FAMILY Act has by far the most traction in Congress. Introduced in the Senate by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and in the House of Representatives by Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), this bill would bring paid leave to new mothers in all U.S. states and territories. In some ways, it is more generous than the iteration of California’s paid leave that Stanczyk examined because it includes a higher wage-replacement rate of 66 percent of a claimant’s full-time wage. While job security is still not guaranteed in the proposed federal legislation, this proposed program could decrease the risk of poverty for the nation’s most vulnerable working mothers.

Still, the higher earnings requirements for the FAMILY Act, in comparison to those in CA-PFL, may make benefits less accessible to working mothers with very low incomes.

When weighing the pros and cons of the FAMILY Act and other paid leave proposals, federal policymakers should pay close attention to Stanczyk’s findings. With proper attention to the data, Congress could pass a bill with the power to keep the nation’s most vulnerable mothers out of poverty.