New labor market data suggest that U.S. wage growth may be cooling too much

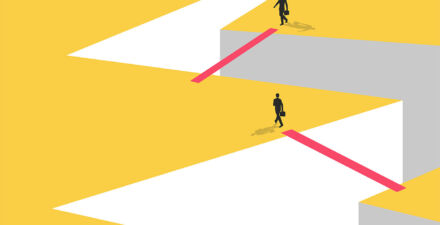

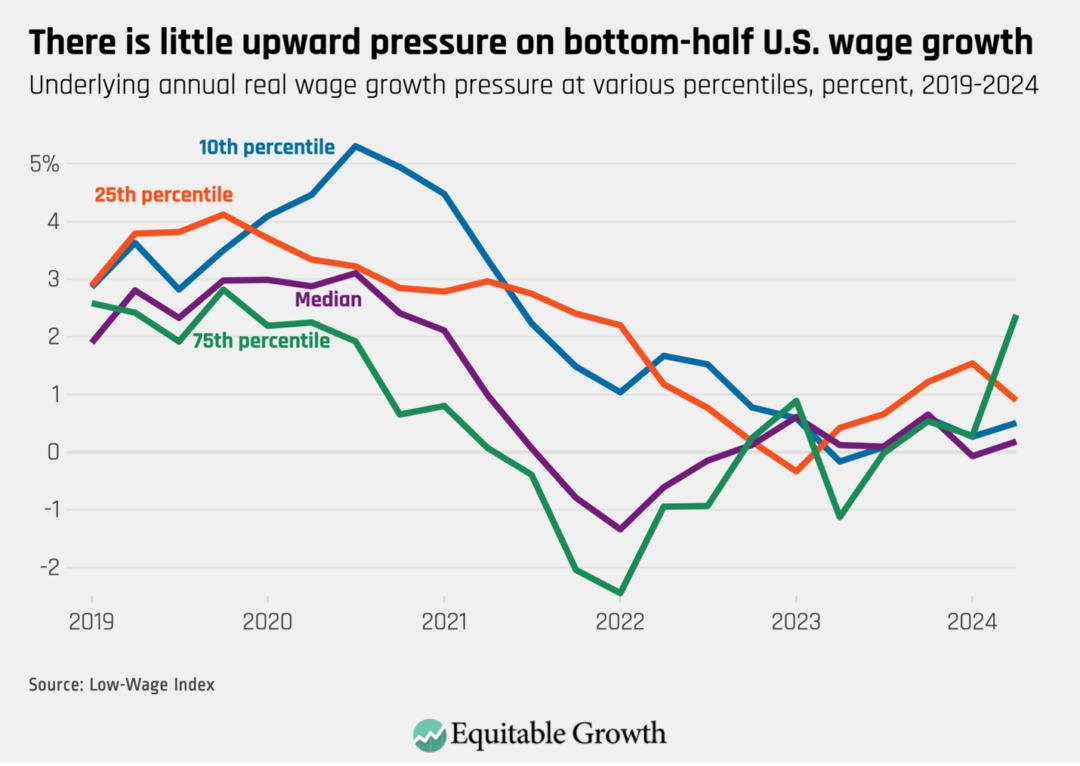

After increasing rapidly over the course of 2021, nominal wage growth (before accounting for inflation) in the United States has been trending down consistently across measures since early- to mid-2022. This has generally been regarded as a positive development because inflation also increased rapidly in 2021, and slowing nominal wage growth tends to reduce upward pressure on prices. This reduced pressure may have contributed to the slowdown in inflation also seen since early- to mid-2022. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Yet U.S. labor market data released over the course of last week suggest that it may be time to reconsider that opinion. When labor productivity grows faster, there is more room for nominal wages to rise without increasing inflation. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, labor productivity in the second quarter of 2024 was 2.7 percent higher than it was a year earlier—the fourth consecutive quarter with annual productivity growth of at least 2.4 percent. (For reference, labor productivity growth averaged 1.3 percent annually from 2010 through 2019).

New data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, or JOLTS, also show a continuing slowdown in hiring. While the bureau’s monthly jobs report’s household survey shows that people ages 25–54 remain employed at high rates, the data also reveal that the overall U.S. unemployment rate rose again, to 4.3 percent, triggering the Sahm Rule, an indicator with a strong track record of identifying recessions in real time. While these signals are somewhat mixed, unemployment has been rising since the beginning of 2023, a clear sign of a cooling labor market.

In this context, the continuing declines in nominal wage growth come amid greater capacity for faster wage growth due to productivity gains and amid broader signs of increased labor market weakness. Add in the progress made in reducing inflation over the past two years, as seen in the green line of Figure 1, and slower nominal wage growth seems less like a necessary cost of stabilizing prices and more like a threat to the labor market’s ability to deliver material gains for workers by boosting their real wages after accounting for inflation.

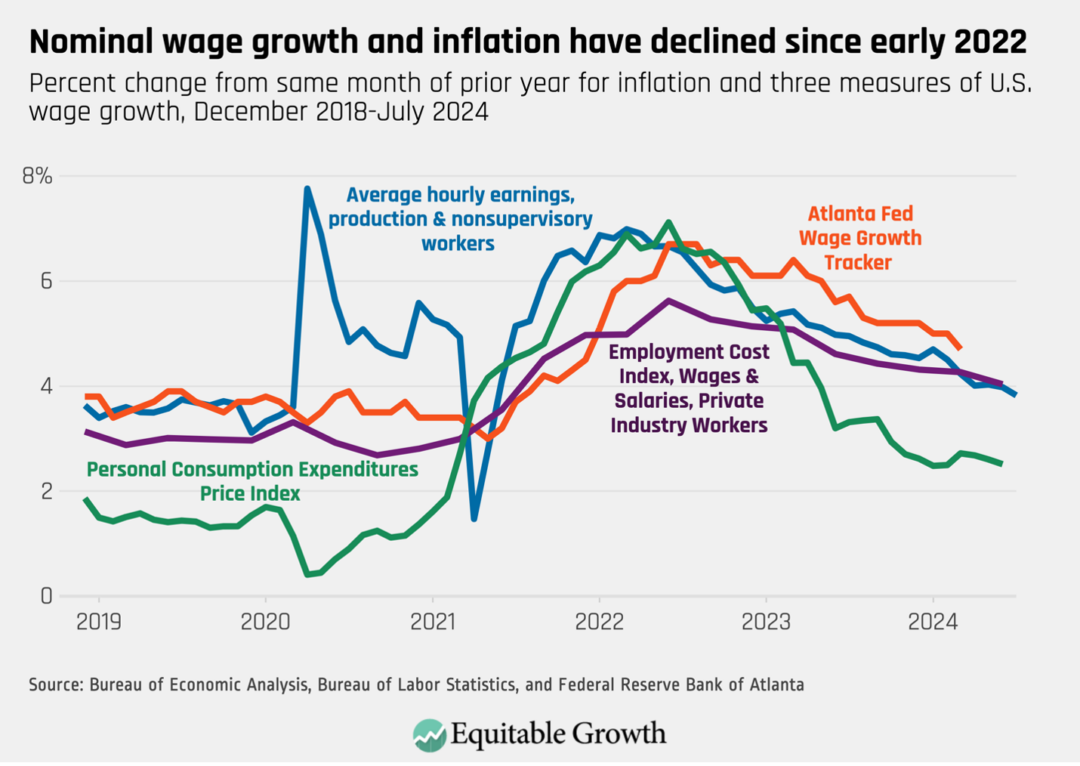

This gloomier view is reinforced by signs that nominal wage growth is likely to slow further going forward. One such sign is the unusually low amount of labor market churn, or the sum of hires and job separations. This measure is often used as a proxy for opportunities for workers to change jobs, which is an important indicator because it represents the chance for workers to get a bigger raise than is typical when continuing on with their current employers.

Last week’s JOLTS report shows labor market churn falling, driven by similar declines in both hires and separations. Given the still-high rate of employment among prime-age workers between the ages of 25 and 54, the current low level of churn is especially unusual. Churn today is more in line with what might be expected if the prime-age employment-to-population ratio were more than 4 percentage points lower than it is—a level last seen in the substantially weaker labor market of 10 years ago. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

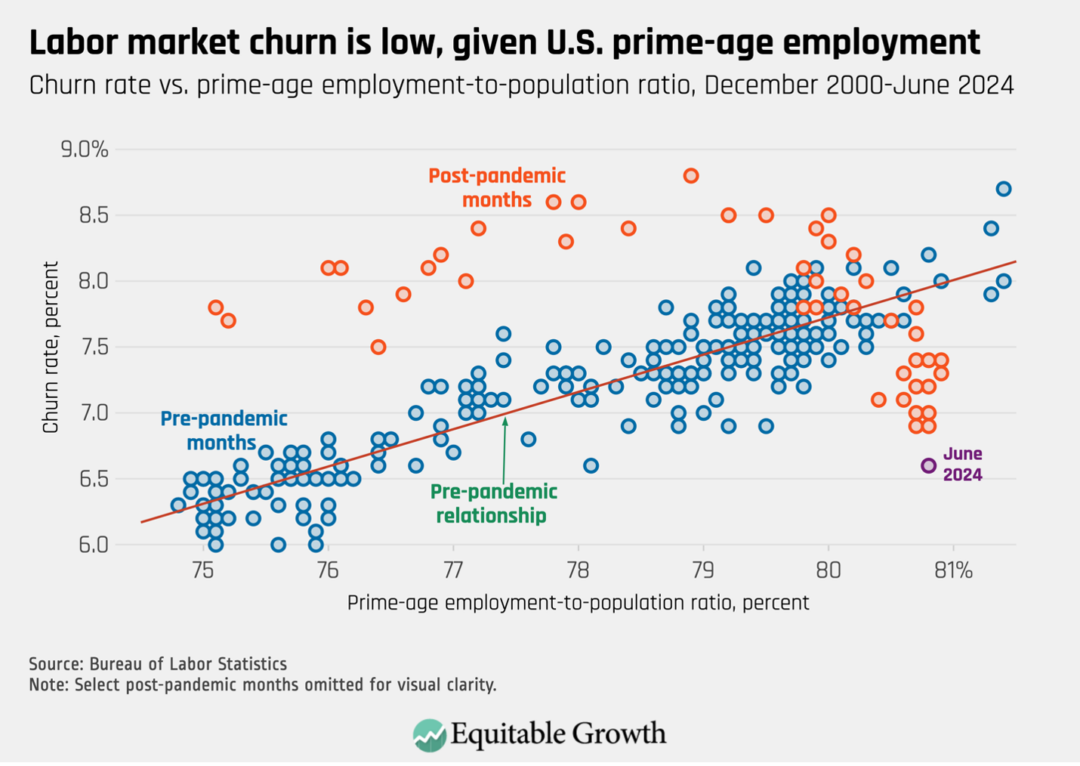

Nominal wage growth tends to be slower when churn is lower. Based on this historical relationship, the 6.8 percent churn rate, on average, over the past 3 months points to nominal wage growth over the next year of between 2 percent and 3 percent—a meaningfully slower pace than the current rate of around 4 percent. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

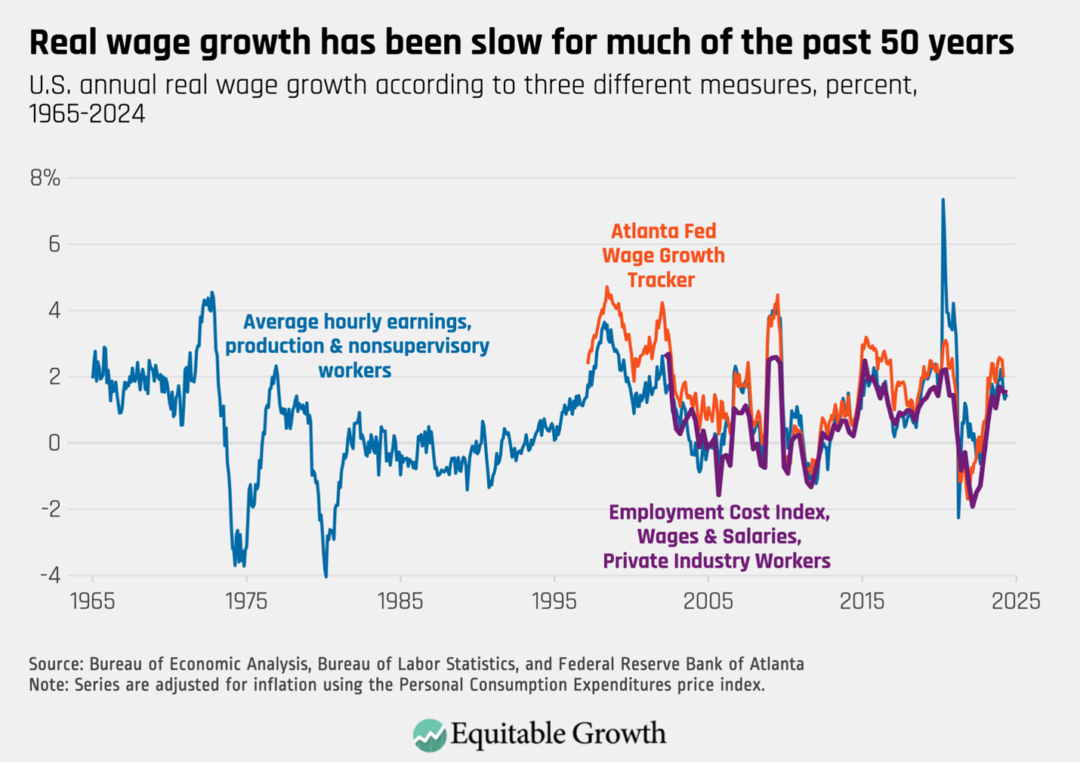

Another sign pointing toward slower nominal wage growth comes from the Low-Wage Index. This new measure, from Yale University economist Ernie Tedeschi using BLS data, aims to capture changes in U.S. wages due to fundamental economic forces rather than changes in the composition of the workforce. Importantly, it measures the influence of these forces at different points in the wage distribution, providing a sense of how low-wage workers are faring, as well as those earning closer to average wages.

These data currently show little upward pressure on wages throughout much of the distribution. For the past year or so, the Low Wage Index has pointed to little-to-no annual change in real wages at the middle and bottom of the distribution, with somewhat larger but still modest and fluctuating gains at the 25th and 75th percentiles. (See Figure 4.) No change in real wages implies nominal wage growth in line with inflation, which has been lower than recent nominal wage growth and is slowing.

Figure 4

This experience of nominal wage growth meaningfully exceeding inflation and producing real wage gains has been all too rare over the past 50 years. Over the past 12 months, annual real wage growth for production and nonsupervisory workers, adjusted for inflation using the Personal Consumption Expenditures price index, has averaged nearly 1.7 percent.

Since the beginning of 1974, only 118 months (out of 606, or 19 percent) have had annual real wage growth faster than that. In 392 of those months (65 percent), annual real wage growth has been below 1 percent, and it has been negative in 208 months (34 percent). Other measures of real wage growth that are available for more recent years and less susceptible to compositional changes show similar trends. (See Figure 5.)

Figure 5

A well-functioning labor market should raise standards of living broadly throughout society. At times, there can be tension between the competing desires to see workers’ earnings rise and to keep prices from increasing too quickly, since higher wages can contribute to higher prices, which can also make people worse off.

Yet the meaningful cooling in the labor market and slowdown in inflation over the past 18 months make slowing wage growth the greater threat to U.S. workers’ well-being. At current rates of productivity growth, declines in nominal wage growth should not be required for inflation to continue to decline. Since only a relatively small decline in inflation is required to reach the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target, the prospect of a continued slowdown in nominal wage growth now looks more like a step back toward a labor market in which workers merely tread water rather than progress toward one in which gains are stable and broadly shared.

Did you find this content informative and engaging?

Get updates and stay in tune with U.S. economic inequality and growth!