Misvaluations in local property tax assessments cause the tax burden to fall more heavily on Black, Latinx homeowners

Authors’ note: We stand in solidarity with all who speak up, all who are hurting, and all who are combating racism and fighting to advance justice. Violence against Black bodies and the repeated loss of Black lives at the hand of the police must stop. We must also put an end to all forms of systemic discrimination that people of color face every day. We will continue to stand against violence and racial injustice in all its forms.

Imagine a town in the United States where residents have agreed to a 1 percent property tax rate. Does the actual rate of taxation depend on which part of town you live in? Is it higher or lower for certain minority racial or ethnic groups than for White homeowners?

In new research, we document large, national inequality in local property tax administration. Looking within regions where every homeowner theoretically faces the same rate of taxation, we find that minority homeowners nonetheless end up paying a 10 percent to 13 percent higher tax rate on average within the same local property tax jurisdiction. For the median Black or Hispanic homeowner in the United States, this translates to an extra $300 to $400 annually in additional property taxes. In highly minority communities, the extra tax burden can be several times as large.

Our research shows this particular inequality arises from a central feature of how property tax bills are calculated. State laws authorizing property taxes make it very clear that the property tax burden homeowners face is intended to be proportional to the market value of their homes. Market values of homes, however, are only observed when a home sells, which happens infrequently. So, property tax bills are based on estimates of market value. This estimate is called a property assessment and is assigned to each home annually for tax purposes by some local official—in most places, by a county assessor. The tax bill that individual homeowners receive is generated by applying the local policy rate to this property assessment.

Consider again the example of a town which has approved a 1 percent property tax. For a home actually worth $200,000, this means the homeowner should pay $2,000 annually. But if that home incorrectly receives an assessment of $300,000, then the homeowner will be billed $3,000—an extra $1,000—even though the home is not actually worth more.

In our paper, “The Assessment Gap: Racial Inequalities in Property Taxation,” we document the national prevelance of misvaluation such as in the scenario described above and show that the result tends to disadvantage minority homeowners. We use extensive administrative data comprising tax records from 118 million residential properties along with market prices from 53 million real-estate transactions to compare property assessments with market value at the only instance in which both values are known: immediately pursuant to a sale.

We compare property assessments done immediately before an arm’s length sale (within the same tax year) with the realized market value of that home. If property taxes are equitable, then the ratio of assessed value and market value should be the same for every group of residents being taxed by the same set of governments (a county, city, and independent school district, for instance).

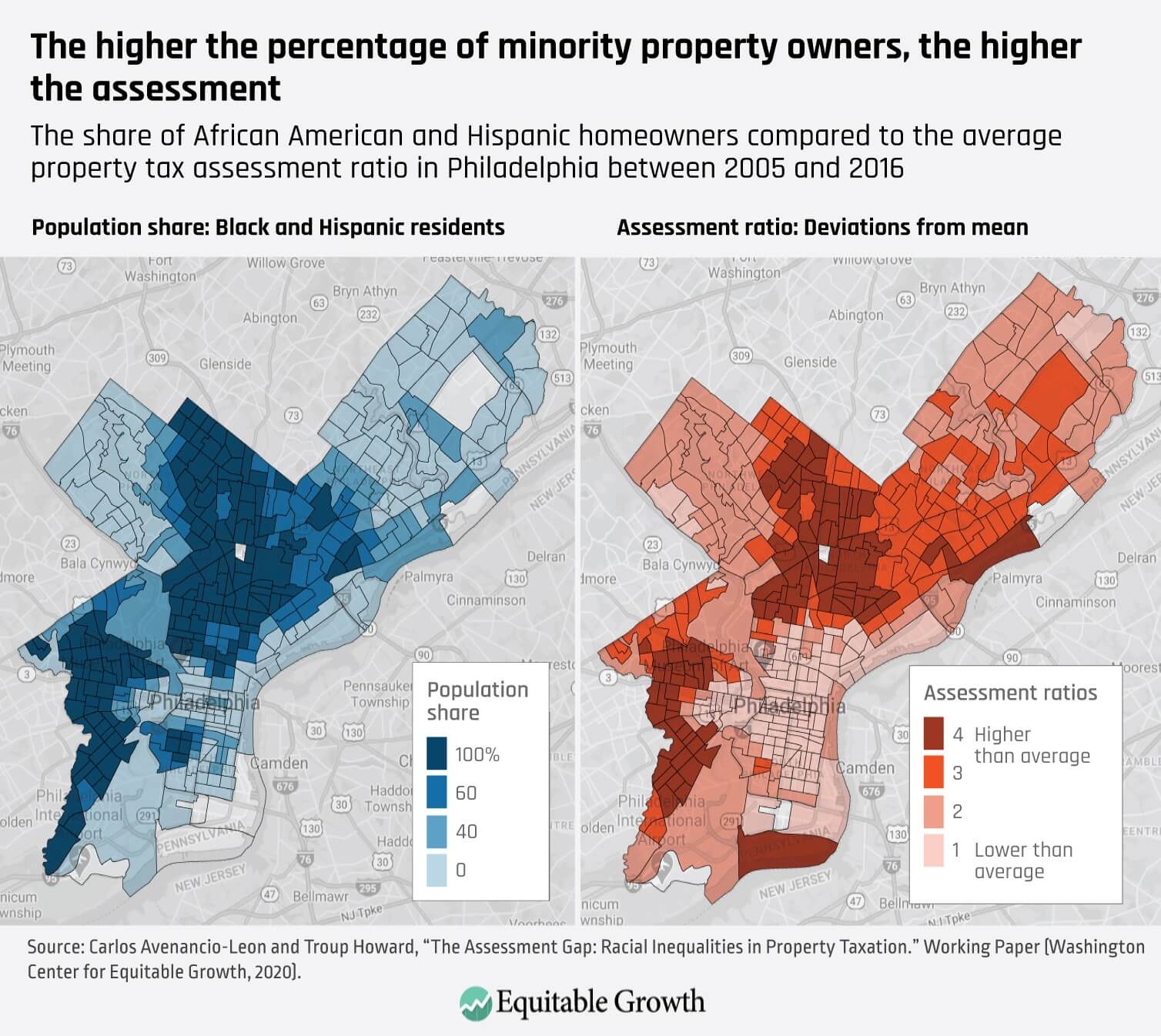

Our central finding is that the average home’s assessment ratio (assessed value divided by market value) is 10 percent to 13 percent higher for a Black- or Hispanic-owned property than for a White-owned property. This means that Black and Hispanic residents receive higher property tax bills for homes of similar value, resulting in minority residents paying a higher property tax rate for the same set of public goods and services. Our assessment of this dynamic in Philadelphia captures this inequality in property taxes. (See Map 1.)

Map 1

We find that the wedge between assessed values and market values arises in two ways. The first relates to residential segregation within local property tax jurisdictions. Market prices are highly sensitive to local attributes. If a home is located directly next to something that homeowners value—a public park, for instance—then the price of that home will be higher to reflect the desirable location. To maintain property tax equity, the assessment should also take into account this local feature that raises market value, yet we find that local property tax assessments are much less responsive to highly local, neighborhood-level attributes than market prices are.

Our results suggest that when market prices and assessed values disagree, that divergence isn’t driven by attributes of the home itself, such as the number of bedrooms or size of the home. Rather, the difference arises from hyper-local neighborhood-level characteristics, which do affect market prices but are inadequately reflected in assessments.

Why does this spatial mismatch between market values and assessments generate racial and ethnic inequality? It is well known that residential racial sorting in the United States is relatively high. One direct result of this racial segregation is that Black and Hispanic residents live, on average, in different neighborhoods than White residents—even within a single taxing jurisdiction. For a White resident, the average neighborhood amenities tend to push market prices up. So, when assessments don’t track this value, these homes end up undertaxed. In parallel, when Black and Hispanic residents live in areas where local amenities push market prices down, this is also not reflected in property assessments, leading to overtaxation.

This spatial dynamic generates a little more than half of the total inequality in the local property tax burden, amounting to an additional $200 to $275 per year for the median Black or Hispanic resident. We also show that this type of inequality sharply increases with neighborhood demographics, leading residents in highly minority portions of a given taxing region to face effective tax rates up to 25 percent higher than residents living in majority-White neighborhoods within the same region.

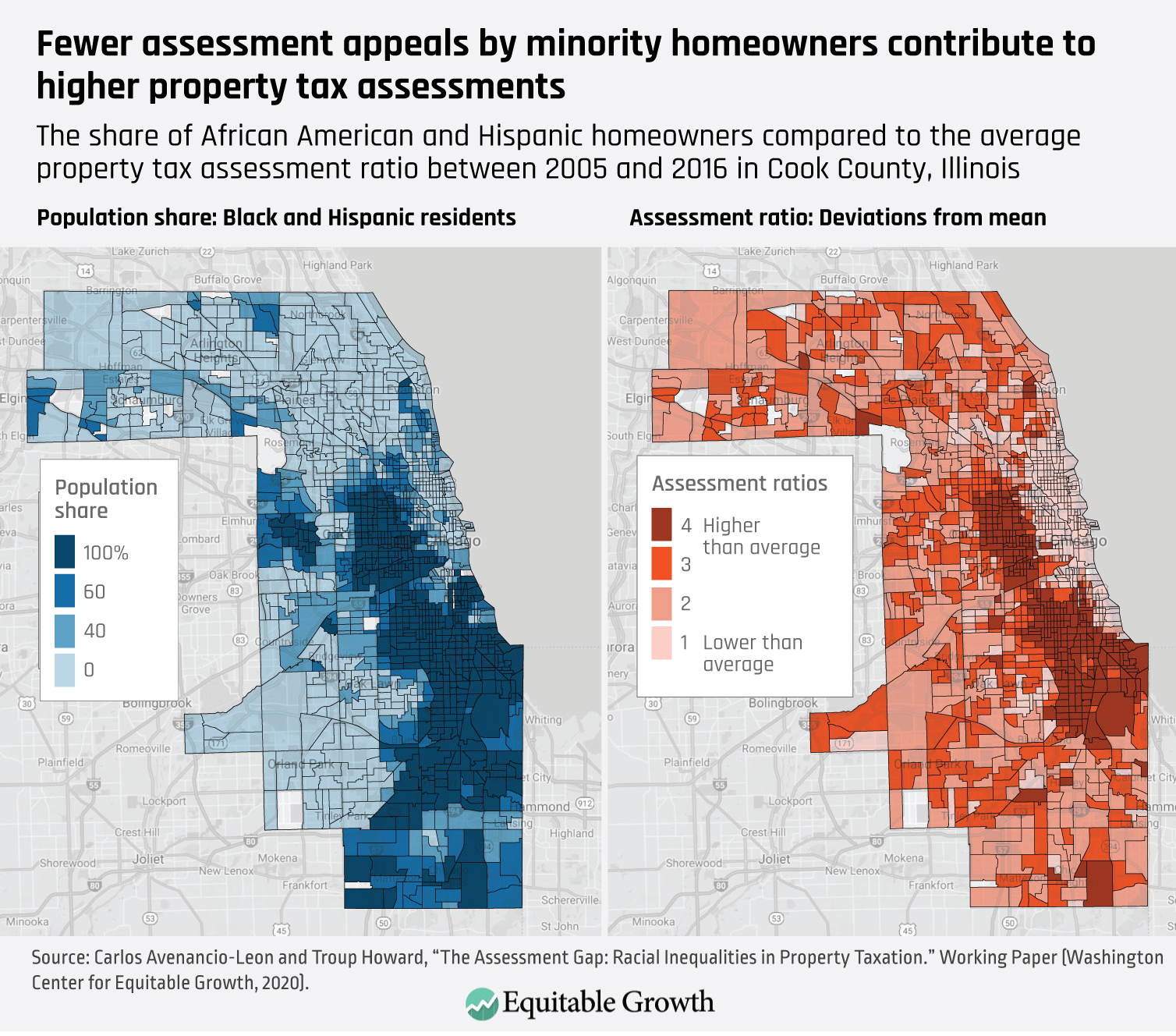

The remaining inequality in tax burden persists within neighborhoods. To understand this type of inequality, imagine two homes on the same city block, one owned by a White resident and the other by a Black resident. On average, the Black-owned home will still have a higher assessment relative to market value than the White-owned home. We argue that this within-neighborhood inequality arises from racial differences in appeals by homeowners about their individual property tax assessments.

Homeowners are typically able to contest their property assessment by filing an appeal through some public bureaucratic process. Using data on 3.5 million appeals from Cook County, Illinois, we find that within U.S. Census Bureau block groups (“neighborhoods” ranging from 600 to 3,000 people), Black and Hispanic residents are less likely to appeal their assessment, less likely to succeed once they have filed an appeal, and, even after succeeding, receive a smaller reduction.

Map 2

In our paper, we outline a simple approach for a more equitable administration of local property tax assessments. Recognizing that insufficient responsiveness to highly local geographic variation generates at least half of this particular kind of inequality, we propose tying the growth of property tax assessments to small-geography home price indexes. In the paper, we show that simply using publicly available ZIP code indexes can reduce total inequality in property tax assessments by up to 70 percent.

The optimal implementation would use indexes that are smaller and more carefully calibrated to local characteristics than ZIP codes, as we describe in our paper. But the broader point is that assessors can significantly reduce overtaxation of highly minority communities by adopting a rules-based approach that is highly sensitive to differences between small neighborhoods.

—Carlos Fernando Avenancio-León is an assistant professor of finance at the Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, Bloomington. Troup Howard is an assistant professor of finance at the David Eccles School of Business, University of Utah.