June jobs report: What the coronavirus recession means for foreign-born workers in the United States

June was a month of strong employment gains. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ latest Employment Situation Summary, the economy added 850,000 jobs between mid-May and mid-June, well above the average month-to-month growth of 540,000 jobs of the previous 3 months. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio, a measure that captures the share of U.S. adults between the ages of 25 and 54 who are employed, increased slightly from 77.1 percent to 77.2 percent.

Amid a strong report, however, the overall unemployment rate actually rose slightly from 5.8 percent in May to 5.9 percent in June, led by reentrants to the labor force and workers leaving their jobs. At 61.4 percent, the labor force participation rate is just 0.2 percentage points above where it was at this time in 2020. Adding 343,000 jobs, the leisure and hospitality sector continued to make big gains in June, but in other industries, net employment declined. Construction lost 7,000 jobs, and financial activities lost 1,000 jobs.

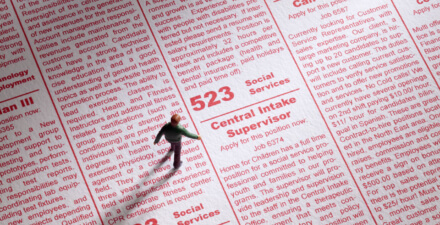

In addition, job gains continue to be greatly uneven along the lines of race, ethnicity, and gender. For Latina women, employment has shrunk 5.9 percent since the onset of the coronavirus recession. In June, 763,000 fewer Black women were employed than in February 2020—a 7.2 percent decline with respect to its pre-pandemic level. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

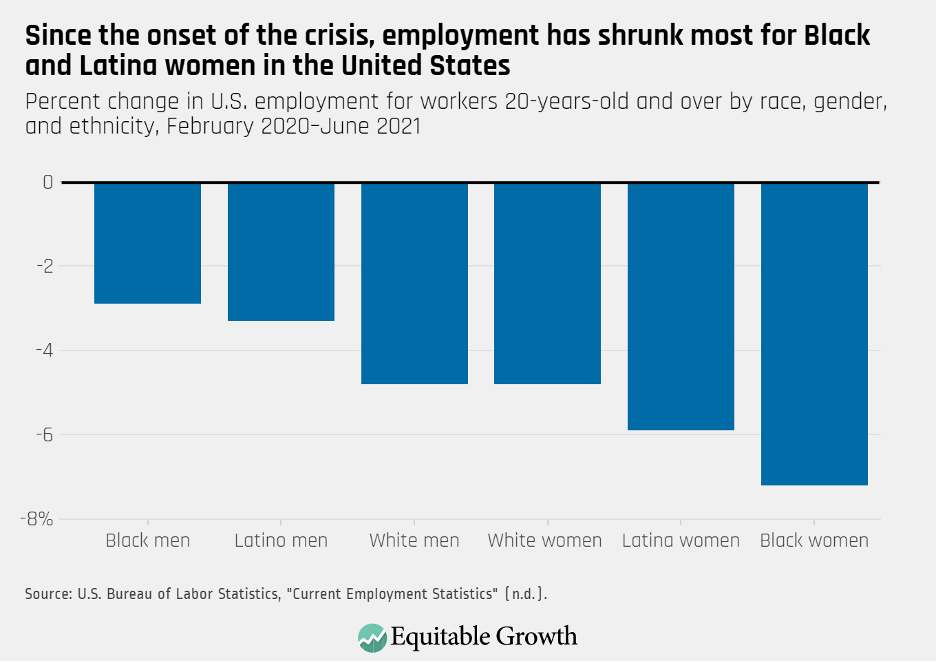

Another group that has been hit hard during the coronavirus recession is foreign-born workers in the United States. Between February 2020 and June 2021, the number of foreign-born workers employed declined 5.9 percent, compared to a 3.1 percent fall for U.S.-born workers. For both foreign- and U.S.-born workers, the decline in employment has been much deeper for women. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics also show that a substantial share of the decline in the U.S. labor force from 2019 to 2020 can be explained by the large number of foreign-born workers who dropped out of the labor force over that period. Strikingly, while workers born abroad only make up 17 percent of the employed or unemployed adults in the United States, they account for almost 40 percent of the overall drop in the U.S. labor force in that time period. In other words, foreign-born workers represented 1.1 million of the 2.8 million workers who stopped participating in the labor force from 2019 to 2020.

What is driving these disparate labor market outcomes? An analysis by Rakesh Kochhar and Jeffrey Passel at the Pew Research Center found that while 42 percent of U.S.-born workers held jobs which could be done remotely in February 2020, only 31 percent of foreign-born workers had the ability to telework.

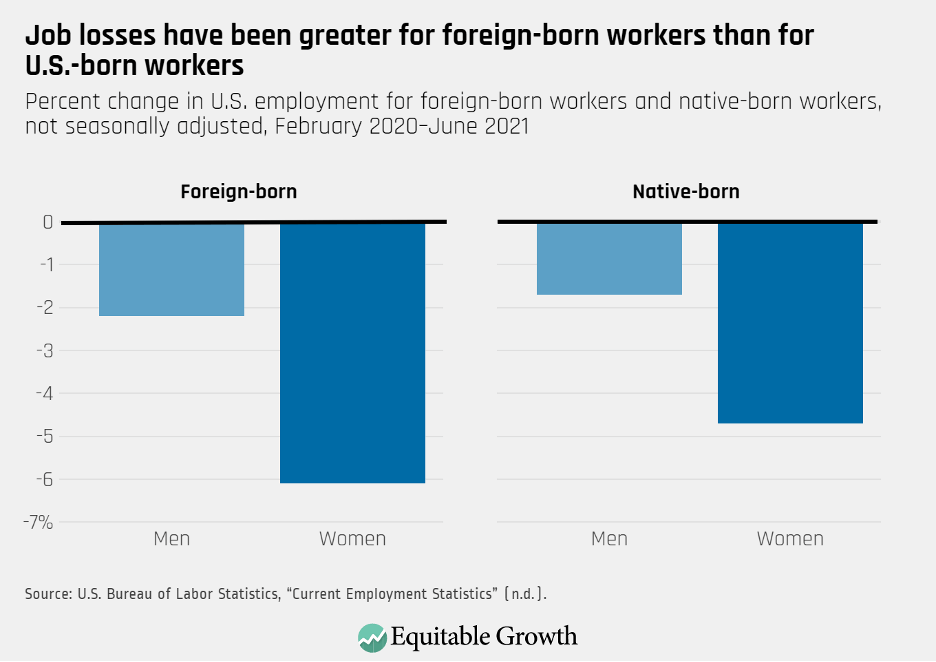

Foreign-born workers are also more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to work in some of the occupations that were most affected as the health and economic crises sent ripples through the U.S. economy in 2020. For instance, more than 20 percent of workers born outside of the United States were employed in service occupations in 2020—jobs in food preparation and serving, for example—compared with just more than 14.4 percent of native-born workers. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

In addition, foreign-born workers are also overrepresented among the essential workforce. Research by Donald Kerwin and Robert Warren at the Center for Migration Studies, for example, estimates that while 65 percent of native-born workers hold jobs categorized as essential by the Department of Homeland Security—jobs in sectors such as meatpacking and poultry processing, agriculture, construction, and healthcare—69 percent of all foreign-born workers do. For undocumented workers, that number climbs to 74 percent.

Foreign-born workers also make up a disproportionately large share of the workforce in sectors in which workers are most at-risk of contracting the coronavirus—food or agriculture has been the deadliest sector, according to a study by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco. Alarmingly, workers in food manufacturing, agriculture, and other essential occupations are also among the most likely to still be unvaccinated.

As such, the fact that foreign-born workers also face barriers to accessing many worker protections and income supports that are most needed during economic downturns—not to mention amid a global pandemic—leaves them particularly exposed to economic insecurity, as well as to the risk of getting sick. Under the current Unemployment Insurance system, for instance, immigrant workers not authorized to work in the United States are not eligible for unemployment benefits.

Immigrant workers are also less likely to apply for assistance programs even when they are eligible for them. A recent analysis by the Urban Institute finds that immigrant adults and families eligible for income support and social insurance programs, such as Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, often decide not participate out of concern that doing so will hurt a green card application process or that information-sharing will lead to the deportation of an undocumented family member.

Even as the U.S. labor market is on track to a robust and relatively quick recovery from the coronavirus recession, there are still 6.8 million fewer jobs than prior to the pandemic. Workers who have been historically excluded from labor market opportunities and protections are at risk of being left behind in the recovery. This not only diminishes the economic security of vulnerable workers, but it translates into a less competitive labor market, lost productivity, and a drag on economic growth.

More than 9.5 million workers actively looking for a job in the United States do not have one. Despite the fact that many workers and families are still struggling, as of the release of this column, 26 states have decided to slash federally funded Unemployment Insurance benefits prior to their official expiration date in early September. Rather than cutting these vital benefits, policymakers should enact permanent reforms that expand UI benefit duration, level, and eligibility, including to freelance workers, seasonal and temporary workers, gig workers, undocumented workers, and workers who do not have a recent work history.

Policymakers should also ramp up the enforcement of labor standards. Research shows that violations to labor law such as wage theft are prevalent in sectors such as agriculture, and that workers who are not U.S. citizens—and Latina noncitizen women in particular—are especially vulnerable to these violations.

Perhaps most urgently, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration—which, at the onset of the pandemic, had the lowest number of workplace inspectors in more than four decades—should be strengthened to guarantee workers are protected during the ongoing pandemic. Ensuring that all workers are protected and have access to the income supports they need is essential for a strong and equitable recovery.