Overview

Equitable Growth in Conversation is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other academics to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability. In this installment, Equitable Growth Director of Competition Policy Michael Kades speaks with Michelle Meagher, a senior policy fellow at the University College London Centre for Law, Economics and Society and co-founder of the Balanced Economy Project, which is building a global anti-monopoly movement. Previously, Meagher worked as a lawyer in private practice for global law firms (Linklaters LLP, Allen & Overy LLP), national regulators (the Office of Fair Trading in the United Kingdom and the Federal Trade Commission in the United States), and the International Finance Corporation at the World Bank Group. Her work on legal policy focuses on public interest, market regulation, and corporate responsibility. She is most recently the author of Competition Is Killing Us, a book about corporate power and accountability and the myths embedded in free market capitalism and shareholder primacy, which was chosen by Martin Wolf at the Financial Times as a Best Economics Book of 2020 and shortlisted for the Financial Times and McKinsey Bracken Bower prize in 2018.

In a recent conversation, Kades and Meagher discuss:

- The Balanced Economy Project and the missing infrastructure of antitrust policy

- The global monopoly problem

- The problem with worshiping competition

- The broader impact of failing competition on the environment and society

- The monopoly problem with global supply chains

- The problem of monopoly power in global economic development

- The big antitrust and competition research questions

Michael Kades: Michelle, thank you so much for being with us. You’ve had a really interesting journey. You’ve started in a very traditional antitrust lawyer role and now have moved on to a more policy-based view. I would love to get your take on how you ended up where you are today and why.

Michelle Meagher: I should start by saying thank you so much for having me here. It’s a real pleasure to be here talking with you. As you say, I’ve had a bit of a journey in getting to where I am today. I go into it a little bit in my book. And to really understand it, I think it helps to go back to, way back, to my teenage years. As I confess in my book, I was a teenage Thatcherite and a real believer in free markets. I think that’s the starting position, which is that I truly internalized this idea that having more competition was a good thing and that free, competitive markets were a good thing, and it’s something that we should spread across the world.

Taking that message, I started out studying economics as an undergrad, and then I went to law school, and then into private practice, and then later served government regulators and to the World Bank. I was really attracted to competition law and competition policy more broadly because it’s that amazing mix of economics and law. You are dealing with the intricacies of the law, but you’re doing so in the context of what I believe is one of our foremost tools in structuring the economy. I think that something that’s really coming out of some of the more recent debates around antitrust in the United States and competition policies in Europe is this understanding about all the different ways that competition policy really touches on these really fundamental questions about how we organize our economy.

I started out with the idea that the way we should organize our economy is through competitive markets. And where that got me was into the heart of the competition establishment, promoting free markets at the front line. Then, in 2013, I had a bit of a lightbulb moment, when I realized two things. The first is that untrammeled, unrestricted free market competition wasn’t necessarily an unalloyed good—it’s not necessarily always a good thing. And secondly, that somehow, despite having a really busy regulatory system that is really its own industry in terms of the scores of lawyers, economists, regulators, advisors, lobbyists, and others who are involved in that system, we somehow are not achieving even what we want to achieve on the very basic metric of success for competition policy.

We are not keeping markets competitive, and that evidence has really only grown over the past few years. Evidence of rising mark-ups [the difference between the price and the cost of a good or service] and rising concentration all around the world really forces us to ask a lot of questions about how that regulatory system is set up. So, that’s how I came into competition policy, but also how I ended up questioning whether it was achieving what it’s meant to achieve.

Kades: I have to say, one of my favorite parts of your book is that lightbulb moment occurring while you were calculating market shares or HHI numbers, which certainly is something I can relate to as well.

The Balanced Economy Project and the missing infrastructure of antitrust policy

Kades: I want to dig back down into a lot of these issues that you’ve raised. But before we sort of get into the weeds a little bit, I’d like to just ask: You have recently started the Balanced Economy Project. It’s a really interesting approach. What’s the goal and your vision for the role for the Balanced Economy Project?

Meagher: We’re at a really exciting stage of the project. We’re just getting started. The project came out of the ideas in my book. I’d written this book that really interrogated and challenged our prevailing system of competition policy, challenged these fundamental concepts of competition, of corporate power. We are really trying to expose a lot of the mistakes that have been made along the way in how we’ve interpreted those concepts and applied them in our enforcement practice.

Meanwhile, obviously, this is against the background of under the rising anti-monopoly movement in the United States, which has been a thorough rethinking of that Chicago School of antitrust doctrine, and a lot of energy in the United States, which previously had been, in a way, an antitrust backwater. There had been almost no enforcement and no interest in antitrust for decades, and if there had been any activity, it had been in Europe, although I would say that the successes had been moderate.

Coming out of my book, I was starting to ask myself, why is there no equivalent anti-monopoly movement of the kind that we see in the United States? Why is there no equivalent movement in Europe? There were other people who were asking these questions, too.

The people who I’ve teamed up with have backgrounds in the tax justice movement. They’ve spent the past 15 years doing exactly what we hope to do: explaining a complex legal area to a very broad set of constituencies and achieving incredible material legal change and culture change within the tax justice field. In so many of the issues that they were touching on in the tax justice world, the problem starts with the issue of corporate power.

One of my co-founders, Nick Shaxson, had written a blog which was titled, “If tax havens scare you, monopolies should, too. And vice versa.” We got in touch based on that blog and found that we had a real shared interest, but also that the tax justice movement could bring something to the anti-monopoly conversation from their experience. We have complementary interests and skills. I was bringing insight as a former insider in the competition world, and Nick was bringing insight from a macro perspective of finance and global financial flows, global capital flows, national competitiveness. All of these issues are so linked with the issues of corporate power and antitrust, but in ways that, actually, the existing analysis doesn’t really bring that out.

Our goal with the Balanced Economy Project is really three things. The first thing is we are planning on building on the energy and momentum of the U.S. movement—building on the narrative debunking the Chicago School and so on, but adapting that for outside the United States. There’s a different story that can be told of how we got to where we are today in Europe. There’s a different story you can tell in Latin America, in sub-Saharan Africa, in Asia, and so on.

The second thing is to build capacity among civil society to actually engage in these issues. We have talked to dozens of civil society organizations that are, in all sorts of different ways and in their separate silos, dealing with issues of monopoly, of corporate power, but they are not seeing that there is a umbrella issue here of anti-monopoly, and they are not connecting their issues to really powerful tools in existing policy instruments—namely, antitrust. Because the language and the process of antitrust has become such a technocratic exercise, it’s really taking place outside of public scrutiny. And I would say the language of monopoly, certainly in Europe and outside the United States, has really been lost to the public discourse.

You do not see discussions about monopoly on the front pages of our newspapers. It’s a hidden issue, and I think there’s a perception that we have less of a monopoly problem in Europe. The idea is to enable civil society to raise their concerns if there’s a merger or to help them challenge an abusive dominant position, using language that is actually understandable and acceptable to the competition authorities.

The third thing we are doing is making sure competition authorities are actually open to civil society. That requires building an infrastructure that is at least as powerful as the extremely effective corporate lobby, which has been able to shape our understanding of antitrust over the past few decades. I think a huge part of why that’s happened is because there hasn’t really been a counter voice. Where are the other stakeholders in that conversation? Are they paying visits to the competition authorities and other regulators and policymakers? Are regulators actually getting that breadth of wisdom that they might be able to get if that broader antitrust civil society infrastructure were there?

So, that’s what we’re trying to do. It’s extremely ambitious in terms of global scope, in terms of the kinds of issues that we’re interested in, and in terms of the entrenched ideas and forces that we’re trying to tackle. But equally, it feels like now is the time. People are asking why have we not made progress in all of these other social, environmental agendas? And the thumb on the scales in many cases is monopoly and corporate power. You can trace the line back to that as a really central reason for why we aren’t able to move forward on so many other agendas. So, I think it’s an issue whose time has really come. Obviously, that’s evident in the United States, but I think it’s also the case outside of the United States as well.

The global monopoly problem

Kades: You point out that there’s a similarity of stories across the world, which is a perceptive insight. The United States has a monopoly problem, as does Europe. It exists in South America and really across the world. But by only looking at it as a national problem, which is the way we’ve looked at it in the United States, we miss something. Could you expand briefly or provide an example of how putting together the stories and synthesizing them gives us a richer understanding of the problem and potential solutions?

Meagher: I’d say, on a basic strategic level, that many of the companies whose power we would want to hold to account operate on the international stage. So, it seems obvious to me that the response needs to be similarly international. We know from decades of experience with global multinational corporations generally that they have the ability to engage in regulatory arbitrage, that they are able to set the regulatory agenda through multilateral organizations and through international trade treaties, and through geopolitical standoffs between different countries.

In some cases, what you’re seeing is the effectuation of, in some ways, various corporate motives. I don’t mean to paint the picture of some sort of evil boogie man or whatever lurking in the background. This is more of a clear-eyed understanding of how some of these global forces work and understanding that they are influenced by national monopolies, and that monopolies maybe headquartered, for legal purposes, in one particular country but oftentimes, when they’ve become a monopoly of a very prominent or very substantial market, they will then have global influence.

Companies don’t have to have that big of a market share of a global market to have really substantial economic power and power that’s often more substantial than some of the countries with whom they will end up negotiating. So, I think that it makes sense to us that we should be thinking about this as an international issue.

I also think we should be thinking internationally because across jurisdictions, many of the solutions may be similar. Encouraging alternative business models, for example, and encouraging countervailing power, and looking at ways to disperse power through society are not only similar solutions across the world, but also can’t necessarily be achieved by any one nation because you end up with the question of what happens to the flow of the world financial capital. How do these solutions impact my country relative to another? It seems to me that a lot of these solutions really become more powerful when you look at them across regional blocs, when you look at tying together the different possibilities across different nations.

This is certainly true in Europe in relation to the U.S.-headquartered tech companies. What happens in the United States will be hugely influential. But you can see that Europe is also forming its own strategy, and it makes sense that other countries would be interested in what these strategies look like. What could work in Latin America? What could work elsewhere? So, I think there’s also a level of information sharing and sharing of experience that will allow civil society and regulators really to get a handle on some of these really tricky questions.

The problem with worshiping competition

Kades: I want to turn back to your book, which has an arresting title for an antitrust person: Competition is Killing Us. Normally, antitrust folks think competition is a good thing. But you open with the story about the garment factory collapse in Dhaka in 2013 that led to deaths of more than 1,000 workers and its relationship to the how markets operate, which is really compelling. So, I just wanted to put to you, in what ways is competition killing us?

Meagher: I think that that’s one of the areas where I get the strongest pushback. Reading my book, I think it’s clear that I’m putting myself into the progressive camp of antitrust reformers, but it’s true that the majority of that camp is pushing for more competition. I think that that’s actually a simplistic understanding of what is really quite a nuanced debate because the point here really is that there are many situations in which competition isn’t good.

Nobel Prizes have been won in recent years explaining the limits of market competition, understanding the extent to which markets are imperfect, particularly the ways in which economic actors are able to externalize costs and—critically, for what I’m talking about—the ways in which those imperfections can be exploited to the advantage of incumbents so that they are actually not faced with competition. In actual fact, they are able to use their competitive techniques to effectively avoid competing with future rivals because they’re able to entrench their power.

So, at a structural level, we have the reality that competition doesn’t seem to work very well, and the insight that we get from this understanding relates to these externalities. My book brings together these two fields—antitrust policy and corporate governance—and the insight we get from the corporate governance space is that the imperatives of shareholder value, which we don’t really think about or talk about in the antitrust world, have a huge impact on how companies compete.

Antitrust policy doesn’t really look inside companies to understand what motivates their economic actions. The assumption is that good things will happen when firms compete. But if we understand and interrogate the concept of shareholder value and the way that influences how businesses operate, then we understand that there is an inherent motivation to monopolize and to externalize that motivation in anticompetitive actions. So, it really matters how businesses compete if we want to stick with our paradigmatic assumption that competition is good.

On another level, if we look at competition within antitrust policy as a concept, as opposed to how companies actually compete in the real world, then we can trace back the line from Borkean thinking and look at how it’s been really abused. The Chicago School posits that we tell whether something’s competitive or anticompetitive via a useful proxy: consumer welfare. But since we can’t directly measure consumer welfare, the Chicago School uses price as the proxy, watching for increasing prices and reductions in output.

Suddenly, then, we’re so far away from looking at either the externalization issue or the monopoly issue. We’re left with a very narrow concept of competition, this idea that as long as we end up with low prices, then we must be in a competitive world because how else would we have ended up with those low prices? This kind of circular way of thinking has done us a huge disservice and really speaks a lot to why we’ve ended up with the concentrated markets that we have today.

Competition is problematic in all those different ways, not just in terms of how competition actually manifests, but also how we’ve abused that concept of competition. We still don’t really have a consensus understanding of competition and its benefits and how it works. What counts as competition? What counts as anticompetitive? These are issues that we are still wrestling with, and it’s because we are looking through the wrong end of the telescope. We should be really focused on power, focused on looking at how power proliferates in the economy. What structures of industrial organization allow for power? What ways does it manifest?

Just looking at competition is a luxury that we no longer can afford precisely because we’ve ended up with such distorted markets. I think it is not possible to say we could have free competitive markets now because they are so distorted. So, the antitrust enforcement that we need now must focus on power and then maybe, eventually, we might get to a point where we can start thinking about the pure concept of competition without looking at these broader issues. But I think we’re a long way off from that.

The broader impact of failing competition on the environment and society

Kades: This idea of externalities really interests me and is something we at Equitable Growth have been thinking about. What is your take on the relationship between competition policy and broader economic development issues or issues such as climate change, racial equity, and political power? How do you see the broader impact of this failure of competition policy?

Meagher: There’s a technical link between monopoly and inequality, environmental degradation, and so on. I think it’s a question that researchers are only just empirically starting to look at. I know a project at Oxford University where they’re looking at the link between monopoly and inequality. I don’t know anybody looking at monopoly and environmental climate change. I hope that there are some out there because I think that’s a really rich area of research.

There’s a technical question of whether it is the case that monopoly really does exacerbate those issues. But if we take a step back and again think about it from the externalization point of view, and understanding that, to a large extent, this is how companies compete, then we recognize that companies compete by producing better products at lower prices if they can. They compete by trying to monopolize markets. And they compete by lowering their costs by externalizing those costs if they can get away with it.

What that means is a lot of what we think of as efficiencies, in antitrust context, looked at in another way could be viewed as externalized costs or exploitation. I think that’s one of the reasons why the increasing interest in monopsony buyer power is so interesting. Because, in my view, that’s something that cannot be squashed into consumer welfare because it may very well be, in a consumer welfare sense, good and efficient and lead to lower prices to squeeze your suppliers, squeeze your workers, provide them poorer terms of employment and supply, and so on. But clearly, there’s a cost then born by society by allowing those economic arrangements to exist. It feels to me like looking at half of the picture if we’re only looking at the efficiencies that result without looking at these externalized costs like exploitation and so on.

Another step removed from this view is to look at it more from the political economy perspective. These issues of climate change, of racial equity, of income inequality, of colonization and the fallout of empire, and the existence of the Global North and Global South points to some structural systemic issues. One of those issues is distortions in markets and the political power of organizations with concentrated economic power and the ability to leverage that power into other spheres.

The monopoly problem with global supply chains

Kades: Can you give an example of the externalization of this global monopoly power?

Meagher: We really see that in the context of global value chains. When we look at global value chains, we are stepping out of monopoly in a textbook sense of looking at a domestic market and a single player who ends up monopolizing one market for a particular product, an output, and then leveraging their power against consumers. Suddenly, when we’re talking about global value chains, we’re talking about a huge geospatial split between consumers, say in the West, or producers in the Global South, the way that powerful firms are able to control the value distribution within those chains, the extent to which they can extract value.

In a concrete way, this is how production exists in countries such as Bangladesh, and how cocoa farmers are paid in West Africa, and so on. There is a huge connection of these externalities and the way power manifests in these value changes across the globe.

The problem of monopoly power in global economic development

Kades: I want to dig down on another insight from your book that I haven’t seen others talk about, which is how monopoly power affects the economic development or inequality between richer and poorer countries or, as you just described, between the Global North and the Global South. Could you give an example? Because I think it’s a really interesting insight of how to think about the impact on different countries.

Meagher: If you take any of the global megamergers, if you look at the enormous mergers in agriculture such as the acquisition of Monsanto by Bayer AG, these and other global mergers are really decided in courts of the United States or the European Union. In an antitrust sense, they’re decided in both, but obviously, the impacts are felt all over the world and many of the other jurisdictions that might want to challenge those mergers might not have the political power to do so. They may not be able to muster all of the resources.

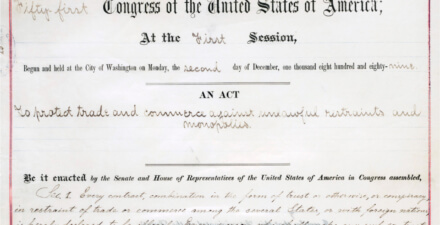

Then, there is this historical artifact. A lot of these Global South jurisdictions effectively have their own antitrust policies that were imported from the United States and the European Union, and in some cases, they are even more Chicago School than the Chicago School. The U.S. Sherman Antitrust Act doesn’t actually use the words “efficiency” or “consumer welfare,” but often, those do crop up in these other laws in other countries, which were a modern transplant of antitrust thinking from the early 2000s and have now been sealed in amber and fossilized into these other jurisdictions. So, you get a very powerless response to a lot of these consolidations of power that are going on among global companies.

This is something that we’re really interested in at the Balanced Economy Project. We want to understand the entire system of monopoly—all of the economic, financial, regulatory policies and institutions and structures that tend to push in the direction of consolidated power. It’s not just weak antitrust policy. That has been a huge factor. The bankers and people who are pushing through mergers are pushing against an open door of antitrust policy, but they were pushing pretty hard as well. We have many forces that are pushing in that direction of consolidation.

I think that’s another piece of the puzzle to understand, both at the geopolitical level, including in terms of the distribution of wealth across nations, but also within nations. We get vast disparities between financial centers and rural, countryside, or regional towns and villages and cities, and elsewhere. We’re also interested in that extractive mechanism—the way in which wealth tends to concentrate in those financial centers and the huge ripple effects.

Take the example of a rural American town, where wealth used to circulate around that town when they had a vibrant Main Street, but is now sucked out by the presence of a Big Box store. Those profits aren’t circulating around that little town anymore; they’re being taken up to Walmart headquarters. If you imagine that on the global scale, we’re also seeing that happen between whole nations. Some nations are that poor American town. We see those ripple effects in all sorts of different ways.

We’re really interested in how all of those pieces fit together. But we’re also asking: What are the useful leverage points to start to change those systems? I do think a lot of it starts with those big picture questions.

The big antitrust and competition research questions

Kades: One of the things we ask everyone in our In Conversations is what they see as the research that’s needed. If you could wave a magic wand and get one or two or even three papers examining antitrust and competition issues more broadly, what would they be?

Meagher: Well, I’m involved with the Anti-Monopoly Fund’s call for research proposals. I’m on the Steering Committee that’s reviewing the proposals submitted to that call. The kinds of things that I’m really interested in are exactly these issues we’ve been discussing. When I’m making these arguments, I want to be able to say, “If you’re wondering is there really a link between monopoly and inequality, environmental degradation, social inequity, here’s the research that shows it.”

Specifically, I would love more research on concentration and evidence of concentration in Europe and outside of the United States. My understanding is that the datasets aren’t as good, and that there are various reasons why that research hasn’t been done. But it seems to me that if we’re going to have this really expensive global antitrust or competition regime, we should at least have the data to check whether we’re doing a good job or not. This means we should be investing in the kind of research that would allow us to know whether markets are consolidating and really sink down into the granular level.

There’s quite a lot of research on competition policy in the developing world and in the Global South, but it doesn’t connect to these progressive debates. I’m interested in research that looks at what progressive antitrust policy would look like in Global South jurisdictions. And what are the ways in which those relatively differently powered nations are actually able to challenge power at the global level? I would say that the United Kingdom is a one of these nations now, a relatively less empowered nation. When the United Kingdom was in the European Union, it had that kind of collective power. Now, it’s on its own. Where does that leave it? The U.K. competition regime is highly sophisticated, but I would love to see discussion of what could now be done with that legacy and deep understanding about these competition issues. How is it able to go up against most powerful companies in the world? And will its competition regime hold power to account?

I am also interested in the broad tent of anti-monopoly policy—so, not just antitrust policy, but also the ways in which we can use tax law and other regulatory tools and the ways in which unions and other structures in the economy are able to counterbalance monopolization forces but also particular instances of monopoly. So, that’s my wish list of research.

Kades: Great. Very helpful. I think those are all great topics. Thank you so much for joining us today and look forward to working with you and seeing your future work.

Meagher: Fabulous. Thank you so much for having me. It’s been great.

Related

In conversation with Herbert Hovenkamp and Ioana Marinescu

Competitive Edge: Crafting a monopolization law for our time

Explore the Equitable Growth network of experts around the country and get answers to today's most pressing questions!