Gender wage inequality in the United States: Causes and solutions to improve family well-being and economic growth

Overview

Disparities between men’s and women’s wages in the United States hinders economic growth by constraining family incomes and spending power. When comparing average full-time year-round incomes of men to those of women, research indicates that women make only 80.5 percent of men’s wages, a gap that is even larger when accounting for race. In the long run, these disparities heighten the risks of financial stress and inadequate retirement savings at times of economic shocks. While a majority of women suffer from unequal wages, the persistence of gender wage inequality heavily affects low-income and single-income families in addition to families of color.

Download FileGender wage inequality in the United States: Causes and solutions to improve family well-being and economic growth

In a 2018 report for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, “Gender wage inequality: What we know and how we can fix it,” sociologist Sarah Jane Glynn breaks the contributing factors to gender wage inequality into two groups:

- Supply-side explanations, which are those related to workers’ differences in human capital investments and include variances in education, race, and choice of occupation. Due to their observable nature, large U.S. Census Bureau surveys can be used to explain the impact that each of these factors has on overall wage inequality. Glynn uses a study by economists Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn of Cornell University that studies how these factors contribute to gender wage differences between 1980 and 2010, allowing them to track the changing dynamics contributing to gender wage inequality.1

- Demand-side explanations, which take into account societal and structural forces that are beyond women’s control and are often associated with gender norms, discrimination, and stereotypes. These factors can be internalized by women and lead them to make educational and occupational decisions that, in turn, show up as supply-side factors. Demand-side explanations reduce women’s earnings by shaping how we value women’s work and characteristics associated with women such as care-work occupations. Subsequent research by Blau and Kahn shows how occupations are paid less by sheer virtue of the share of women in them, and not related to the human capital of the average worker or the productivity of the jobs.

This factsheet presents a snapshot of each of these findings and then presents a variety of policy solutions, among them legislation at the federal level, examples of state and municipal laws that could be replicated in other areas of the country and by the federal government, and federal agency rules and regulations that could be implemented or expanded.

“Unequal pay between men and women drags down the growth of the U.S. economy.”

—Sarah Jane Glynn, “Gender wage inequality: What we know and how we can fix it.”

Supply-side causes of the U.S. gender wage gap

Glynn breaks down the supply-side explanations for gender wage inequality into six groups: work experience, industry and occupation, unionization, education, race, and region. For each group, all of the statistics of gender wage inequality and policies to amend this inequality were pulled from Glynn’s report and Blau and Kahn’s paper.

Work experience

- Years of work experience contributes to 14 percent of gender wage inequality and is responsible for roughly $112.7 billion in wage differences between men and women.

- While female labor force participation has increased in the past four decades, women still have fewer years of work experience compared to their male counterparts because women continue to provide the majority of unpaid care to children, elders, and ill family members.

Policies supporting workers’ access to paid family care hold the potential to increase wages and allow more women to stay connected to the workforce, thus reducing the work-experience gap between men and women. Here are five potential policy solutions.

Potential policy recommendation 1: Child Care for Working Families Act

The Child Care for Working Families Act, introduced by Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) and Rep. Bobby Scott (D-VA), gives guaranteed childcare assistance to families earning up to 150 percent of their state’s median income. In addition, it limits families’ childcare spending to 7 percent of household income and promises improved wages for childcare providers. This policy, which would be paid for by employee and employer payroll contributions, has the potential to create 2.3 million new jobs and increase childcare providers’ wages by 26 percent.2

Potential policy recommendation 2: FAMILY Act

The FAMILY Act, introduced by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), outlines a national, gender-neutral social insurance program that would fund two-thirds of a parent’s wage for up to 12 weeks of paid leave. The program, which will be paid for by employee and employer payroll contributions, sets qualifications and eligibility conditions that will be determined by language of the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993. Research indicates that a national paid leave program boosts women’s wages by 7 percent.3

Potential policy recommendation 3: The Trump administration’s proposed plan

The Trump administration proposed a plan to create a federal paid parental leave program, administered through states’ unemployment insurance systems, that provides parents up to six weeks of paid leave. While this idea grants new parents the ability to take time off without any employment consequences, it would deduct from their Social Security retirement income, thus leaving parents at risk of financial insecurity when their retirement approaches. Unemployment insurance systems are already extremely underfunded and would struggle to implement such a program. In addition, this plan prioritizes parental leave for a new child, thus ignoring family caregiving needs.4

Potential policy recommendation 4: The Schedules That Work Act

The Schedules That Work Act, written by Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT), puts forth protocols—such as requiring clear scheduling expectations from the start of employment—that allow workers to request flexibility from their employers, while protecting workers from financial retaliation or employment discrimination. This policy will allow workers to manage family care needs without risking their income and financial stability.5

Potential policy recommendation 5: State-specific paid family leave policies

Five states—California, New Jersey, Rhode Island, New York, and Washington state—and the District of Columbia have instituted paid family leave laws, though Washington state and D.C. will not activate the law until January 1, 2020. Studies conducted by Jean Kimmel of Western Michigan University and Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes of San Diego State University found that access to parental leave correlated with a 7 percent increase in women’s earnings and shrank motherhood wage inequality by two-thirds. Research on California’s paid family leave system found it has increased mothers’ work hours by 10 percent to 17 percent.6

Industry and occupation

- The differences in gender segregation among industries and occupations accounts for 50.5 percent, or $403.6 billion, of gender wage inequality.

- Of that 50.5 percent, 17.6 percent of this is due to the differences in industries and 32.9 percent is due to differences in occupations in which women and men are typically employed.

- It’s not just that women are overrepresented in lower-paying service-providing industries—wages tend to be lower in occupations that are women-dominated, and there is evidence that there is a causal mechanism at play—but also that an influx of women into an occupation lowers wages.

- Within occupations, women tend to be clustered at the lower end of the wage distribution. Women make up 52.8 percent of legal positions, for example, but only 37.4 percent of lawyers are women, whereas the other 62.6 percent are paralegals, legal assistants, and other legal support positions—all of which have lower wages than lawyers.

Policies that increase wages in industries and occupations that women are currently overrepresented in, as well as policies that enhance access to high-paying jobs in traditionally male-dominated industries, would address some of the pay gap caused by occupational segregation. Here are three potential policy solutions.

Potential policy recommendation 1: Funding for programs such as Women in Apprenticeship and Nontraditional Occupations

The federal Women in Apprenticeships and Nontraditional Occupations program provides resources to diversify the gender distribution of apprenticeship programs, which tend to be male-dominated. Funding for it should remain in order to maintain current apprenticeship programs and create new programs to decrease the gender differences. In 2017, the U.S. Department of Labor announced a $1.9 million investment to “recruit, train, and retain women in high-skill occupations” in a way to increase diversity within the manufacturing, technology, energy, and construction industries. The Trump administration canceled many of these contracts and pledges shortly after President Donald Trump took office. The 2018 and 2019 federal budgets eliminated this grant program funding, which would hurt the administration’s own goal of creating 5 million new apprenticeships over the span of 5 years.7

Potential policy recommendation 2: Expand the National Science Foundation’s ADVANCE grant-making program

Expanding the NSF’s ADVANCE grant-making program to provide competitive grants to univerisities to brainstorm proceeses that promote gender equity in STEM fields, which are highly male-dominated, would increase the representation of women in such fields and encourage pay equity between men and women.

Potential policy recommendation 3: Fully implement the Obama administration’s overtime rule

Full implementation of the Department of Labor’s already promulgated overtime-expansion rule, which would increase the minimum salary for workers exempt from overtime standards to $47,476, would address some of the gender wage gap because the majority of affected workers are women: One-quarter of all mothers and almost 33 percent of single working mothers have salaries at this level. Implementation at the federal level has been stalled by lawsuits by 21 states and more than 55 business groups, but some states have taken action. California, for example, set the threshold to $45,760 for salaried workers, and their wages are linked to the minimum wage, thus the two wages grow in accordance with one another.8

Unionization

- Blau and Kahn found that union participation has reduced gender wage inequality by 1.3 percent, leading to $10.4 billion in increased earnings for women. This is partly due to women’s overrepresentation in public-sector employment, which is more heavily unionized.9

- Collective bargaining agreements raise wages and create industrywide standard wage policies, which reduce the possibility of wage discrimination and thus have been particularly beneficial to all women and men of color. Women whose contracts were covered by unions saw a 9.2 percent increase in wages compared to those not covered by unions. These benefits were experienced at an even greater magnitude by women working in service industries, in which unionization led to women earning 87 percent more in total compensation, compared to nonunion women workers.

- Recent declines in union participation have the potential to hurt wage equality because fewer workers will be covered by unions, and unions will lack funds and resources required for collective bargaining.

Policies that protect and strengthen collective bargaining rights can improve gender pay equity by raising overall wages and setting standard wages based on occupation rather than gender. Here are two potential policy solutions.

“Comprehensive labor-law reform legislation should create meaningful penalties for employers who violate the NLRA so that there is a greater disincentive for bad employer behavior.”

—Sarah Jane Glynn, “Gender wage inequality: What we know and how we can fix it.”

Potential policy recommendation 1: The Workplace Action for a Growing Economy (WAGE) Act

The WAGE Act, introduced in Congress by Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) and Rep. Bobby Scott (D-VA), creates new protections for workers attempting to unionize, including making it an individual right to join a union, which would allow workers not covered by the National Labor Relations Act to organize. It would also impose stricter punishments for employers who violate the NLRA by firing or punishing workers engaged in union organizing.10

Potential policy recommendation 2: Collective bargaining for freelance economy workers

Between 54 million and 68 million Americans work in the freelance economy, according to the McKinsey Global Institute, yet they are not protected by the NLRA due to their classification as independent contractors.11 States and cities are taking initiatives to create fair labor standards for those working in the freelance economy. In 2015, Seattle’s city council passed a rule that grants drivers for Uber Technologies, Inc. and Lyft, Inc. the ability to unionize, though it was being appealed at the time of this writing. In 2016, New York state’s Department of Labor ruled that these drivers are employees rather than independent contractors, allowing them to qualify for greater worker protections and benefits.12

Education

- Gender wage inequality was narrowed by 5.9 percent as a result of women’s increased educational attainment, accounting for a $47.2 billion increase in women’s earnings.

- Legislative and social changes—such as the 1972 Title IX provision of the Education Amendments in the U.S. Code of Laws, greater access to birth control, and delayed marriage timelines—increased women’s educational attainment.

- Despite women earning the majority of postsecondary degrees, the fields of study that they pursue compared to those men pursue lead to lower-wage jobs. Men are more likely than women to major in engineering and computer and information sciences, whereas women are more likely to study education, humanities, or the social sciences.

- “Nontraditional” undergraduates, defined as older students, married students, and/or students with children, face a particular challenge because while both sexes in this category are equally likely to have delayed entry to postsecondary education and to work while in school, women are significantly more likely to be caring for dependents while attending school.

Policies to make college affordable and help nontraditional undergraduates would facilitate higher completion rates of postsecondary education. In addition, policies that increase the number of women pursuing degrees in fields historically dominated by men would increase the chances that women would be employed in higher-paying fields after graduation. Here are three potential policy solutions.

Potential policy recommendation 1: The INSPIRE Women Act and other legislation to increase the representation of women in STEM fields

Legislation such as Inspiring the Next Space Pioneers, Innovators, Researchers, and Explorers, or INSPIRE Women Act, passed in February 2017, as well as Sen. Catherine Cortez Mastro (D-NV) and Rep. Jackie Rosen (D-NV)’s Code Like a Girl Act and Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-HI) and Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY)’s Women and Minorities in STEM Booster Act of 2017, are all examples of legislation intended to increase the representation of women in fields where they are currently underrepresented.13

Potential policy recommendation 2: Increase college affordability

Expansion of the federal Pell Grants program would make college more affordable for students, as they do not have to be repaid. In addition, many states and cities are initiating various programs aimed at making community colleges tuition free for low-income students. Tennessee, Oregon, Rhode Island, and San Francisco already allow residents who qualify as low income to attend community college for free. In addition, beginning in 2017, all City University of New York and State University of New York two- and four-year universities will allow students from households making less than $125,000 annually to attend tuition free.14

Potential policy recommendation 3: On-campus childcare for student parents

The number of student parents enrolled in two- and four-year universities has been on the rise. To keep these students enrolled through graduation, states are investing in on-campus childcare centers for students and faculty. In California, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Nevada, New York, Rhode Island, Utah, and Washington state, 70 percent of all public universities have campus childcare available for students. The investment in on-campus childcare can result in positive returns of a better-educated workforce, higher wages, and greater innovation.15

Race

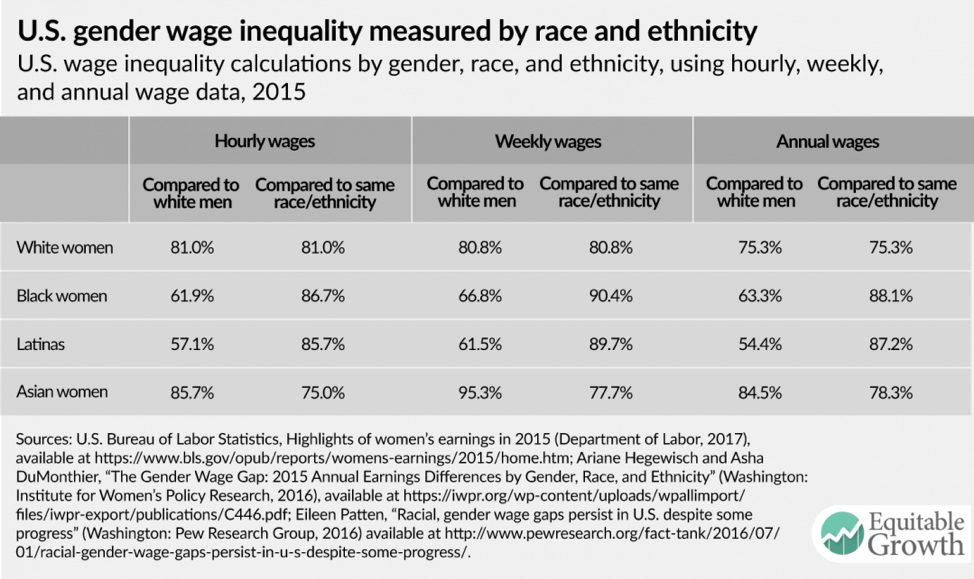

- Race “explains” 4.3 percent of gender wage inequality, according to Blau and Kahn’s model, which translates to $34.4 billion in wage differences for women of color.

- Racial wage inequality exacerbates gender wage inequalities, and the effect of race persists even after controlling for education, work experience, and occupation.

- For example, while wage inequality for women of color has narrowed slightly over time, likely due to their increased educational attainment, as of 2015, black women still earn 34.2 percent less than white men and 11.7 percent less than white women, even after controlling for education, experience, marital status, and region of residence. (See Table 1.)

Table 1

Policies to increase wages and promote educational attainment would help improve women of color’s wages but are insufficient on their own. Policies are also needed to address persistent racial wage and hiring discrimination. Here’s one potential policy solution.

Potential policy recommendation: Collect data to understand problems facing workers of color

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, overseen by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, prohibits employers from discriminating employers based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. Collecting firm-specific employment and pay data would allow the EEOC to better enforce Title VII, but it is not currently collected. In September 2016, the EEOC did announce it would begin collecting summary pay data and aggregate hours worked by pay bands, gender, race, and ethnicity for businesses with more than 100 employees. In August 2017, however, the Trump administration issued a stay before it got underway.16

Regions

- The regions where women live and work accounts for 0.3 percent of gender wage inequality, or a $2.4 billion wage difference between men and women.

- Regional differences in pay affect both men and women, but the effects aren’t evenly spread among them. Part of this is due to differences in states with minimum wages higher than the federal minimum wage and whether states have an equal pay law. States with smaller wage differences were almost twice as likely to have a minimum wage higher than the federal minimum wage rate of $7.25.

While the cost of living varies across state lines, wages usually reflect that region’s cost of living and should be relatively equal between men and women. Policies such as increasing the federal minimum wage would help eliminate gender wage inequality as a result of regional differences. Here’s one potential policy solution.

Potential policy recommendation 1: Increase the federal minimum wage

A 2014 Obama administration analysis found that raising the federal minimum wage to $10.10 per hour would narrow gender wage inequality by 5 percent, which would translate to an additional $24 billion in wages.

Demand-side causes

Most of the factors that contribute to the gender wage gap can be explained by the supply-side causes, yet the source of 38 percent of the wage gap is largely unquantified because of the difficulties in modeling socially constructed gender norms, according to Glynn. All of the statistics of gender wage inequality and the policies to amend this inequality included in this section were pulled from Glynn’s report and Blau and Kahn’s paper.

Socially constructed gender norms and internalized expectations about their behavior play a role in influencing women’s decisions about what education or occupation to pursue. Even the supply-side factors outlined above are seemingly easy to observe and measure, but might be less explanatory than estimated in the Blau and Kahn model. A study on engineering students, for example, found that more women than men changed their majors because the women were more likely to negatively interpret their grades, have lower self-confidence, and have less faculty and peer support compared to their male peers, limiting career prospects in a lucrative field.17

Discrimination also plays a role in the unexplained portion of gender wage inequality. Because earnings at a new job are often based on earnings at a prior job, any discrimination a woman experienced in what she was paid in the past will carry forward and compound in future jobs. After accounting for observable characteristics, Blau and Kahn found that 38 percent of gender wage inequality remains unexplained, which accounts for $303.7 billion in the difference between men’s and women’s wages in 2016. Economists interpret this unexplained portion as discrimination.

“The unexplained [portion of the gender wage] gap will also understate discrimination if some of the explanatory variables such as experience, occupation, industry, or union status have themselves been influenced by discrimination—either directly through the discriminatory actions of employers, coworkers, or customers or indirectly through feedback effects.”

—Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations.”

Policies that increase pay transparency, combat discrimination, and ensure that data about pay differences is collected will help address some of the “unexplainable” differences in men and women’s wages. Here are five potential policy soultions.

Potential policy recommendation 1: Fair Pay Act

The Fair Pay Act, reintroduced by Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC), would expand prohibitions against sex discrimination from “equal work” to “equivalent work,” clarify that any differences in pay must be justified by legitimate business interests, protect workers who share their pay information, and increase damages available to victims of wage discrimination.18

Potential policy recommendation 2: Paycheck Fairness Act

The Paycheck Fairness Act, introduced by Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA) and Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) in 2017, requires employers to prove that differences in pay were a result of business-related factors. This rule would protect workers who disclose pay to other workers, increase employer transparency regarding pay inequities, and hold employers accountable for pay discriminations.19

Potential policy recommendation 3: Workplace Advancement Act

The Workplace Advancement Act, introduced by Sen. Deb Fischer (R-NE) and Rep. Stephen Knight (R-CA), would amend the Fair Labor Standards Act by protecting workers from retaliation for discussing their wages if they do so in order to discover pay inequity among co-workers.20

Potential policy recommendation 4: Eliminate questions about past wages during the application process

Policies that ban employers from asking about wages earned at prior jobs will mitigate the impact of pay discrimination experienced in the past by preventing it from carrying forward to future earnings. The states of Massachusetts, California, Oregon, Delaware, and New York, the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, and the cities of San Francisco, Pittsburgh, and New Orleans have all passed measures to ban the practice.21

Potential policy recommendation 5: Improve data availability on wages by gender

Other countries have laws requiring employers to collect data on their employees’ wages to determine whether male and female employees are being paid differently for the same work. The collection of wage data by gender, race, and ethnicity is necessary to measure what is actually happening and to assess whether policies intended to address gender wage inequality are working, as well as to ensure compliance with those policies.22

To learn more about the research and policy recommendations behind the information summarized here, you can read Sarah Jane Glynn’s full report, “Gender wage inequality: What we know and how we can fix it.”

End Notes

1. Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, “The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations,” Journal of Economic Literature 55 (3) (2017): 789–865.

2. Ajay Chaudry and Katie Hamm, “The Child Care for Working Families Act Will Boost Employment and Create Jobs” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2017), available at https://www.americanprogress.org/ issues/early-childhood/reports/2017/12/07/443783/child-care-working-families-act-will-boost-employment-create-jobs/.

3. Jean Kimmel and Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes, “Effects of Family Leave on Wages, Employment, and the Family Wage Gap: Distributional Implications.”

4. U.S. Office of Management and Budget, An American Budget: Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2019 (Government Printing Office, 2017), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/budget-fy2019.pdf.

5. Schedules That Work Act, S.1386, 115 Cong. 1 sess. (Government Printing Office, 2017).

6.

Maya Rossin‐Slater, Christopher J. Ruhm, and Jane Waldfogel, “The effects of California’s paid family leave

program on mothers’ leave‐taking and subsequent labor market outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32 (2) (2013): 224–245.

7.

Angela Hanks, “The Administration and Congress Should Not Undermine Registered Apprenticeships” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2018),

available at https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/education-postsecondary/reports/2018/01/11/444829/administration-congress-not-undermine-registeredapprenticeships/; Executive Order no. 13,801, Federal Register 82 28229 (2017), available at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/06/20/2017-13012/expandingapprenticeships-in-america.

8.

Caroline Fredrickson, “Majority of Workers Who Will Benefit from Updated Overtime Rules are Women” (Washington: Economic Policy Institute, 2015), available

at http://www.epi.org/blog/majority-of-workers-who-will-benefit-from-updated-overtime-rules-are-women/; Council of Economic Advisors, The State of the Gender Wage Gap (Government Printing Office, 2016), available at https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20160614_gender_pay_gap_issue_brief_cea.pdf.

9. Blau and Kahn, “The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations.”

10. Richard D. Kahlenberg and Moshe Z. Marvit, “Architects of Democracy: Labor Organizing as a Civil Right,” Stanford Journal of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties 9 (2013): 213–244.

11. James Manyika and others, “Independent work: Choice, necessity, and the gig economy” (San Francisco: McKinsey Global Institute, 2016), available at https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/employment-and-growth/independent-work-choice-necessity-and-the-gig-economy.

12. Legal Services NYC, “New York Taxi Workers Alliance, Uber Drivers Win Employee Status,” Press release, October 13, 2016, available at http://www.legalservicesnyc.org/news-and-events/press-room/1055-new-york-taxiworkers-alliance-uber-drivers-win-employee-status.

13. Women and Minorities in STEM Booster Act of 2017, H. Rept. 2709, 115 Cong. 1 sess. (Government Printing Office, 2017).

14. “Tuition-Free Degree Program: The Excelsior Scholarship,” available at https://www.ny.gov/programs/tuition-free-degree-program-excelsior-scholarship (last accessed March 29, 2018).

15. Eleanor Eckerson and others, “Child Care for Parents in College: A State-by-State Assessment” (Washington: Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2016), available at http://www.chronicle.com/blogs/ticker/files/2016/09/Child-Care.pdf.

16. Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, EEO-1 Form; Review and Stay (Office of Management and Budget, 2017), available at https://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/Utilities/Review_and_Stay_Memo_for_EEOC.pdf.

17. Irene F.Goodman, Christine M. Cunningham, and Cathy Lachapelle, “The Women’s Experience in CollegeEngineering” (Cambridge, MA: Goodman Research Group, Inc., 2002), available at http://www.grginc.com/WECE_FINAL_REPORT.pdf.

18. Fair Pay Act of 2017, H. Rept. 2095, 115 Cong. 1 sess. (Government Printing Office, 2017).

19. Paycheck Fairness Act, H. Rept. 1869, 115 Cong. 1 sess. (Government Printing Office, 2017).

20. Workplace Advancement Act, S. 345, 115 Cong. 1 sess. (Government Printing Office, 2017).

21. Mitchell Hartman, “The old salary history question could be on its way out for good,” Marketplace, October 25, 2017, available at https://www.marketplace.org/2017/10/25/world/new-laws-ban-employers-using-salary-history-hiring.

22. Zoe Cullen and Bobak Pakzad-Hurson, “Equilibrium effects of pay transparency.” Working Paper (Harvard Business School, 2017).