For Juneteenth: A look at economic racial inequality between white and black Americans

This Wednesday, June 19, is Juneteenth, the United States’ second independence day, marking the day in 1865 that many black American communities celebrate as the anniversary of their freedom. Juneteenth is now recognized as a holiday or special day of observance in 45 states and the District of Columbia, but these celebrations, while acknowledging how far we have come, also call out how far we still have to go.

Juneteenth is a holiday known to many people, but perhaps not to enough. It marks the day in 1865 when Union Major General Gordon Granger issued General Orders Number 3 in Galveston, Texas, announcing to the people of Texas that “in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” While technically the Emancipation Proclamation had freed slaves living in the Confederacy on January 1, 1863, it wasn’t until Union troops arrived in an area that the law actually started being enforced. And so it was June 19 that the black residents of Galveston—and later, communities across the country—began celebrating as the anniversary of their freedom.

In observance of the holiday, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth is highlighting some of the research and analysis that both we and members of our academic network have done to explore both the persistence of economic racial inequality between white and black Americans today and some of the reasons for it.

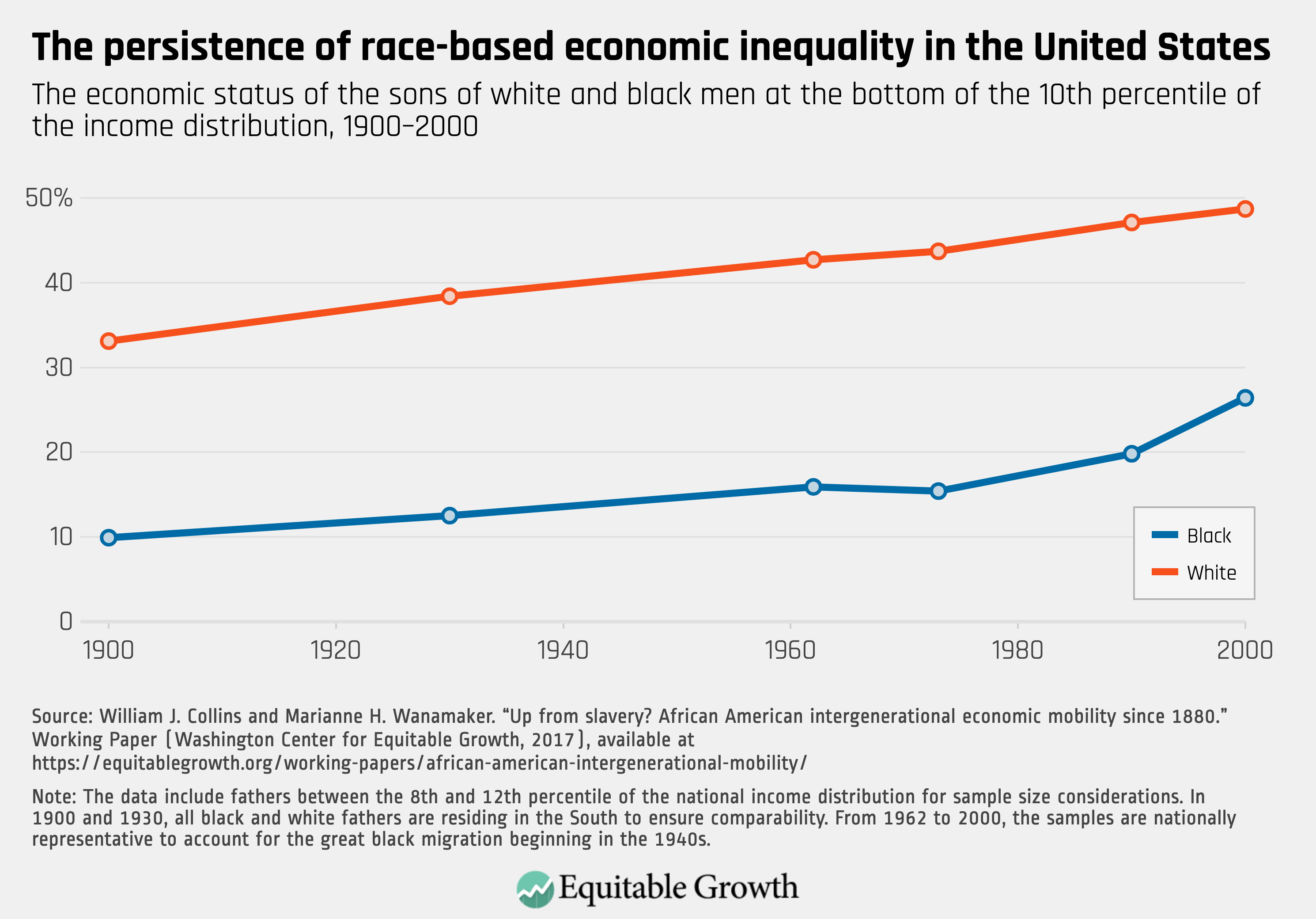

In a working paper for Equitable Growth’s Working Paper Series, economists William J. Collins of Vanderbilt University and Marianne H. Wanamaker of the University of Tennessee analyzed the earnings gap between white and black men to see what its intergenerational persistence says about its causes. They looked specifically at whether poor white families experienced “slow convergence toward the population’s mean earnings historically,” because, as they explain in the accompanying column about their paper, if this is the case, “that would suggest that poverty’s historical legacy has been powerful and that the slow pace of black men’s advance may largely reflect their initial concentration at the bottom of the U.S. economic and social ladders. If not, then it would suggest that race-specific factors have been paramount.”

Collins and Wanamaker find that when you look at the sons of men who were in the 10th percentile of the income distribution, black sons grew up to rank approximately 20 percentile points lower than white sons, on average, across the 20th century, demonstrating the large and persistent role that race—rather than class—has played in the earnings gap between white and black men. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

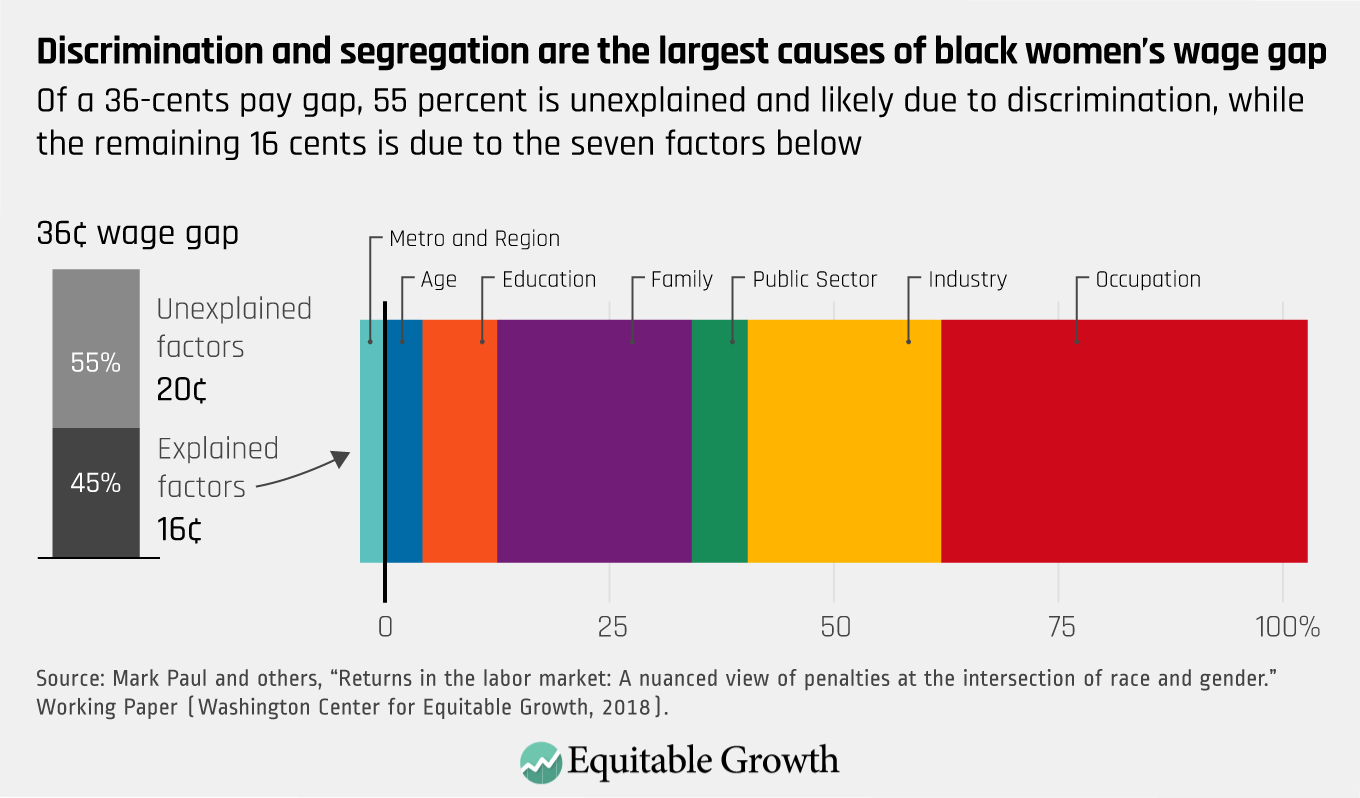

Another Equitable Growth working paper illustrates the extra burden that black women bear because of the wage gaps—plural—that they experience: both the racial wage gap and the gender wage gap. The co-authors, Mark Paul of the New College of Florida, Khaing Zaw of Duke University, Darrick Hamilton of The Ohio State University, and William Darity, Jr. of Duke University, seek to quantify the cumulative impact of being both black and female, and find that the wage gap faced by black women is greater than the sum of its parts, as they explain in an accompanying column. Black women earn just 64 cents for every dollar that white men earn, which is above and beyond the wage penalty they experience when compared to black men and to white women.

Furthermore, Paul and his co-authors find that 55.5 percent of this gap cannot be explained by variables such as education, family structure, occupation, and industry. Differences in education and skills are often thought of as explanations for wage gaps between different groups of workers—and they are, to an extent. But, as this analysis shows us, wage gaps persist, even after controlling for these factors.

But talking about controlling for factors that could be logical reasons why one worker earns less than another overlooks the role that race and gender play in pushing people into certain occupations and industries and in influencing what is deemed to be the economic value of one job versus another job. As Equitable Growth Research Assistant Will McGrew explains, occupational segregation—the over- or underrepresentation of a demographic group in an occupation or industry relative to its share of the population—is one of the largest causes of the “explainable” wage gap black women face. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

The racial wealth gap is even larger than the racial income gap. While white families have median wealth of $171,000, black families have median wealth of only $17,600. Differences in income or education cannot entirely explain the wealth gap between white and black American families—the net worth of black families in the top income quintile is only $262,800, which is barely more than half that of white families in the top income quintile. In a Value Added blog post, former Equitable Growth Policy Analyst Bridget Ansel examined the wealth gap between white and black women, citing a report by Equitable Growth grantees William Darity, Jr. and Darrick Hamilton, among others, that found that even after controlling for education and income, black women had significantly less wealth than white women. For example, “The median wealth levels of single black women ages 60 and older with a college degree is $11,000, compared to a whopping median of $384,400 for their white counterparts, nearly 35 times the black median.”

Just one example of the power of policy to diminish economic racial inequality comes from the job market paper of Claire Montialoux, a Ph.D. candidate at CREST, currently visiting the University of California, Berkeley, and an Equitable Growth grantee. In the paper, co-authored with Ellora Derenoncourt, a postdoctoral research associate in economics at Princeton University and another Equitable Growth grantee, Montialoux and Derenoncourt find that the 1966 Fair Labor Standards Act—which extended the minimum wage to jobs in sectors previously excluded from minimum wage requirements, such as agriculture, restaurants, and nursing homes, and in which black workers were disproportionately overrepresented—can explain more than 20 percent of the decline in the racial earnings gap during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In the more than 150 years since the first celebration of Juneteenth, legal barriers, policy choices, and discrimination have contributed to ongoing economic disparities between white and black Americans. While policy is responsible for many of the causes of the racial income and wealth gaps, that means it also can be used to close them.