Food assistance can disrupt intergenerational poverty in the United States, promoting racial economic equity

The post-COVID-19 economy is a strange beast. Unemployment rates are at historic lows, but inflation—despite some cooling—remains high. Many parents continue to struggle with child care and their children’s schooling, and key income supports enacted in response to the pandemic are expiring. The prospect of recession looms as policymakers debate issues of public spending, debt, and rising interest rates.

Amid this economic uncertainty, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, is a lifeline for millions of families. As negotiations about the budget and the debt ceiling continue to unfold, legislators are currently debating proposals to scale back SNAP benefits and impose stricter work requirements that will make food assistance more difficult to access.

Threats to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program must reconcile with the research on the program’s impressive record of results. SNAP benefits lift millions of families with children out of poverty every year. Moreover, researchers have demonstrated again and again using the most rigorous causal methods that SNAP benefits reduce “food insecurity,” or the inability to meet routine food expenses, while stimulating economic growth. Recent research estimates that every $1 in additional SNAP spending can increase the GDP by $1.54 during economic slowdowns.

These short-term benefits are striking on their own, but the reach of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program into families’ and children’s well-being extends much farther.

Because household resources during childhood have profound, causal, and long-term impacts on children, researchers find that SNAP benefits increase children’s education in adulthood, reduce the likelihood of becoming incarcerated, improve health, and even lead to longer lifespans. Mothers and young children who participate in the program wind up healthier during a crucial period of development. And when families’ food costs are supported by SNAP benefits, they’re able to reallocate their spending to other purposes that might benefit their children. These benefits redound to their children well into adulthood.

Given these established effects, one major unknown is whether the program also has the power to disrupt the cycle of poverty, and long-standing disparities by race in the link between childhood poverty and poverty in adulthood. In our new working paper, “The Effectiveness of the Food Stamp Program at Reducing Racial Differences in the Intergenerational Persistence of Poverty,” with the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, we tackle this question head on.

We use long-term intergenerational data from the University of Michigan’s Panel Study of Income Dynamics to assess whether early exposure to the Food Stamp Program (the precursor to today’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) causally leads to a disruption in the persistence of poverty across generations. And given long-standing disparities in poverty by race, how do these causal linkages result in reductions in racial differences in the intergenerational persistence of poverty?

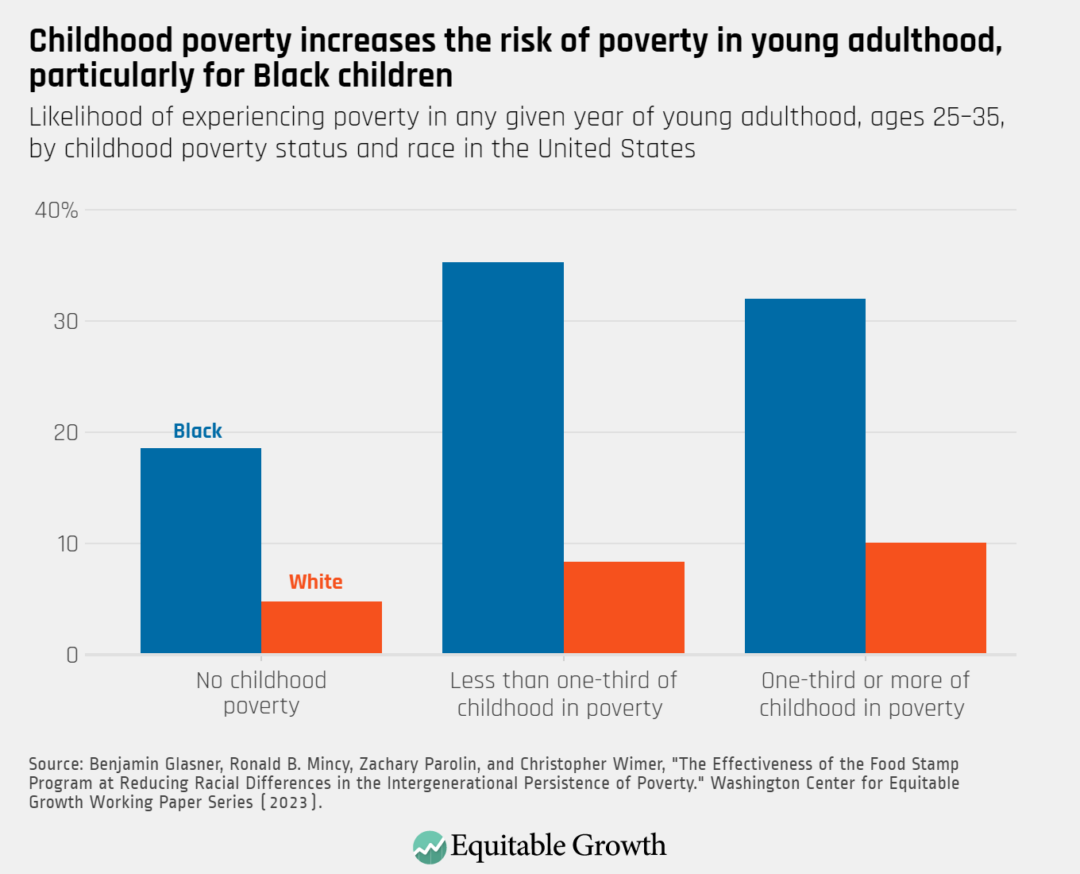

Research previously shows that experiencing poverty as a young child significantly increases the risk of poverty by the time one reaches young adulthood. And in addition to planting the seeds for poverty later in life, childhood poverty appears to exacerbate already deep racial inequities. Black children who experience childhood poverty are three times as likely to be poor in young adulthood relative to comparable White children. (See figure 1.)

Figure 1

Using the latest advances in causal inference based on the county-by-county rollout of the Food Stamp Program in the 1960s and 1970s, our paper finds that exposure to food stamps in early childhood reduces the likelihood of poverty for all adults by 5 percentage points, and that these reductions are strongest for Black individuals whose parents did not finish high school—a proxy for childhood poverty. Among these respondents, childhood exposure to food stamps led to a 7 percentage point reduction in adult poverty.

In addition to reducing the likelihood of overall poverty in adulthood, the Food Stamp Program also reduced the depth of poverty individuals experienced as adults. For Black adults exposed to food stamps as children, we saw an 8.6 percentage point reduction in deep poverty in young adulthood (income less than half the poverty line).

The takeaway is clear: income support from food stamps in early childhood not only has long-reaching effects into adulthood, but also holds power for reducing racial inequality in the cycle of poverty. As policymakers debate the future of policies such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, it is critical to understand this program does more than just reduce hunger and food insecurity. It also contributes to our nation’s widely-shared goal of promoting equality of opportunity. This program’s role in promoting opportunity and mobility promotes both short-term stability as well as long-term economic growth.