Factsheet: How strong unions can restore workers’ bargaining power

Overview

Unions in the United States have long been one of the most powerful institutions through which workers achieved higher pay and better working conditions. In the middle decades of the 20th century, a strong labor movement empowered workers and helped them secure many of the rights and protections that now are also part of many nonunionized workers’ nonwage benefits, including the expansion of healthcare, access to family leave, the minimum wage, and work-free weekends, just to name a few.

Download FileHow strong unions can restore workers’ bargaining power

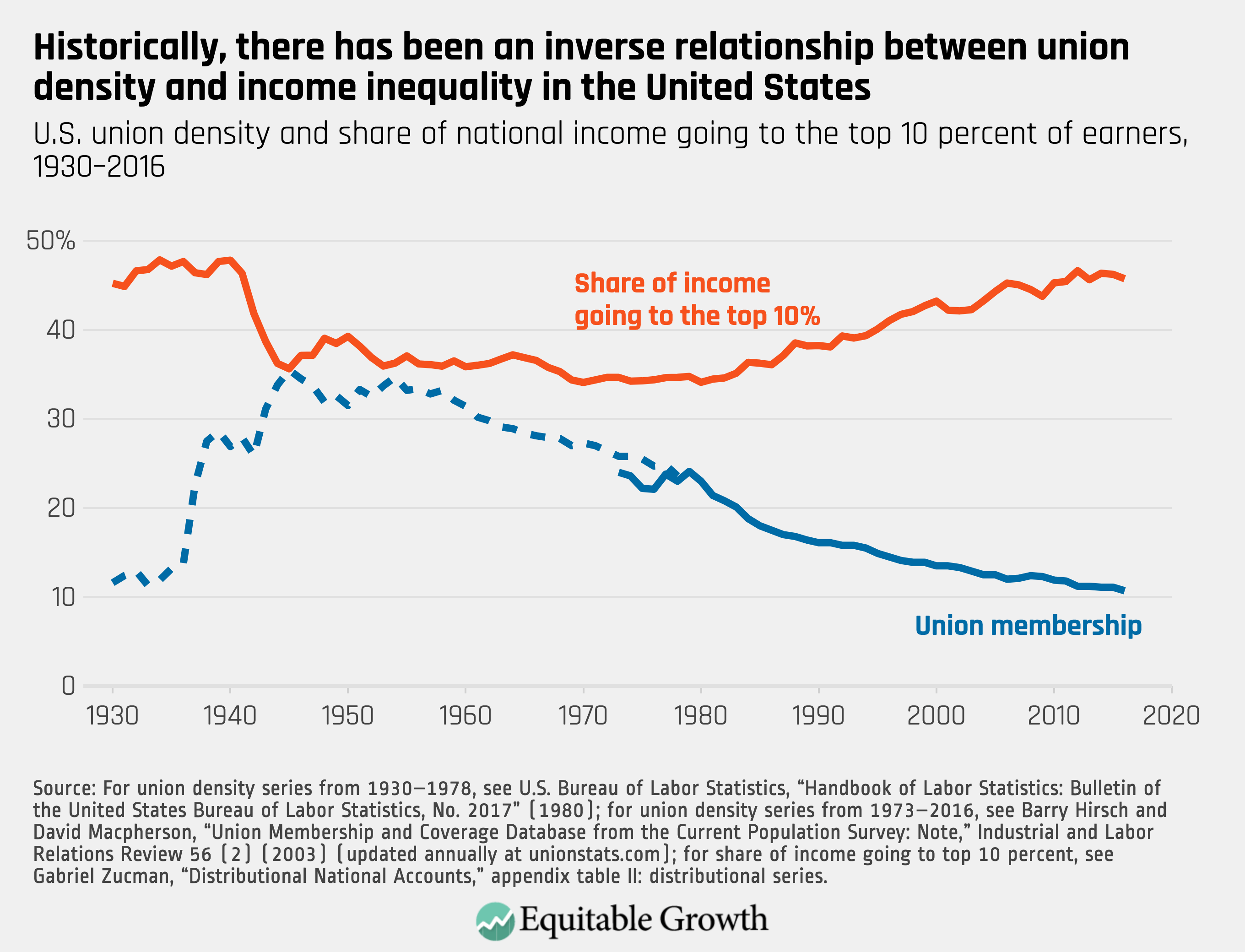

But a decades-long decline of unions has weakened workers’ ability to fight for a fairer workplace. About 10 percent workers are union members today, compared to 35 percent of the U.S. workforce in the mid-1950s. Over the past 40 years, the power of organized labor has declined alongside a steep rise in income inequality, the erosion of labor standards, and employers’ ability to dictate and suppress wages.

Yet unions still play an important role in shaping U.S. labor market outcomes, helping both union and nonunion members share in the economic value they create. This factsheet details those outcomes, including:

- Strong unions benefit both union and nonunion members.

- A small share of workers are part of a union today, but many want to belong to one.

- Strong unions can counteract employers’ wage-setting power.

- Strikes remain a powerful way for workers to achieve fair wages and better working conditions.

Before examining each of these in turn, however, it’s important to look briefly at how the steady decline in the power of unions since the 1970s is one of the most important causes behind the rise of income inequality in the United States.

Rising U.S. income inequality amid declining union membership

At least since 1936, there has been a strong inverse relationship between union membership and income inequality. More than just a story of correlation, research shows that from 1940 to 1970—the decades when U.S. union density was at its highest—organized labor represented a greater share of workers of color and workers with lower levels of education, raising their wages and narrowing the gap between incomes at the top and the bottom of the income ladder. As membership rates declined and the composition of unions changed, however, the equalizing effect of organized labor became less powerful. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

This research on declining union membership challenges an influential explanation of why income inequality has risen sharply since the 1970s. The theory of skills-biased technological change proposes that workplace innovations raised employers’ demand for workers with higher levels of education, leaving behind those without a college degree. According to this theory, highly skilled workers’ improved labor market standing drives them to exit unions because they can obtain higher wages without collective bargaining.

Yet the opposite happened. Unions now represent workers with higher levels of education, and in the past two decades, income inequality has grown most between workers with the same level of education, with women and black workers with higher education degrees experiencing greater pay gaps.

Strong unions benefit all workers

The first set of facts about the importance of unions is that they benefit all workers. Union members have higher wages than their nonunionized peers—what researchers call the union wage premium—but organized labor helps create conditions that make all workers better off. By leveraging the possibility of unionizing, workers overall are in a better bargaining position to negotiate for higher pay and better working conditions.

More generally, strong unions are able to set job-quality standards that nonunion businesses have to meet in order to compete for workers. Known as the spillover effect, this mechanism helps explain why:

- Low- and middle-waged workers experienced important pay and benefits gains during the height of the labor movement in the middle of the 20th century.

- Residents of states with greater unionization rates are more likely to have access to health insurance.

- Average nonunion wages are higher in highly unionized industries.

Strong unions also allow organized labor to institutionalize norms of equity and fair pay. Even though the majority of union members were white and male during the height of the labor movement, organized labor strongly supported redistributive public policies that contributed to narrowing racial and gender pay gaps. Research shows, for example, that collective bargaining’s positive effect on earnings is particularly strong for black and Hispanic workers, helping reduce wage inequality. Likewise, women who are part of a union experience smaller gender wage gaps than their nonunionized peers.

A small share of workers are part of a union today, but many want to belong to one

The second set of facts show that workers are eager to join unions. U.S. labor law and a business environment antagonistic to organized labor prevent many workers from joining a union, yet public attitudes toward the U.S. labor movement have become increasingly positive over the past 30 years. A 2018 study found, for example, that 48 percent of nonunion workers would vote to join a union if they had the opportunity to do so. This number represents an important increase with respect to similar surveys conducted in 1977 and 1995, when only a third of respondents answered they would.

This research also shows that the ability to bargain collectively is very important to workers. Respondents to surveys asking why they wanted to become part of a union answered that the legal right to negotiate wages, benefits, and working conditions would significantly raise the likelihood of them joining a union. Workers were also enthusiastic about the prospect of joining labor organizations that allowed them to access unemployment benefits, as well as portable health insurance and retirement savings coverage.

Strong unions can counteract employers’ wage-setting power

The third set of facts demonstrates why unions can offset employers’ wage-setting power. The decades-long decline in union density has limited workers’ ability to push back against what economists call monopsony power: firms’ ability to use their market power to dictate and suppress earnings. Challenging traditional economic thinking on the wage-setting process, new sources of data have enabled researchers to show that labor markets are often uncompetitive, with wide-ranging factors such as corporate concentration, the widespread use of noncompete agreements, and the declining value of the federal minimum wage making it more difficult to move easily between jobs and, in turn, increasing employers’ power vis-à-vis workers.

Through an exhaustive analysis of the existing literature, researchers find evidence that monopsonistic labor markets are widespread, leading to important markdowns in wages for many workers. Using data from the hiring website CareerBuilder.com, for example, empirical research shows that going from a more competitive local labor market to a more concentrated one was associated with a 17 percent decline in the wages that employers posted on the website.

Unions can counteract monopsony power by limiting firms’ ability to extract “rents” from workers, where rents are defined as employers’ capacity to pay workers less than the value of what they produce. To do so, however, unions need the support of legislation that protects the right to organize, enforcement of regulation that prevents workplace abuses, and policies that allow collective action such as strikes.

Strikes remain a powerful way for workers to achieve fair wages and better working conditions

The fourth set of facts shows why the right to strike remains important. By striking, workers are able to use their labor as leverage and demand higher pay, better working conditions, and protest unfair practices by employers. That strikes are now much less frequent, successful, and popular than during the height of the labor movement has therefore weakened unions’ ability to counterbalance the power of employers.

Yet strikes keep playing an important role in workers’ struggle for a fairer workplace. There has been a significant rise in work stoppages since 2018, and the evidence shows that strikes can continue to be successful tools for the U.S. labor movement, particularly when organizers are able to build up goodwill though political education.

When studying the large-scale walkouts by public schools in 2018, for example, economists found that parents who had firsthand exposure to these strikes were more likely to support and join organized labor. The researchers found that strikes improved attitudes toward unions because educators were able to both leverage school staffing shortages and effectively communicate the worthiness of their demands, convincing parents of the public goods that collective action generates for their children and communities.

How to restore workers’ bargaining power

Unions remain important to all workers, as our sets of facts above detail, but in order to foster broadly shared economic growth, both unions and existing labor law need to adapt to the changing nature of work. During the past 40 years, the erosion of U.S. labor standards and changes in the way firms structure their businesses has made it harder for workers to join unions and bargain collectively.

Rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court have limited the ability of public-sector unions to collect dues, as well as made it more difficult for workers overall to band together and sue their employers for workplace misconduct. Likewise, businesses’ shift away from directly employing workers and toward contracting—a phenomenon researchers call the fissuring of the workplace—hurt workers’ career-advancement opportunities and earnings, as well as unions’ ability to counteract the power of employers.

Because of these new challenges, unions need to advocate for an updated vision for U.S. labor policy. Through their “Clean Slate Agenda,” Sharon Block and Benjamin Sachs of Harvard Law School developed such a framework, creating a series of proposals for structural legal changes that would protect workers and give them the ability to countervail employers’ power. Their recommendations include:

- Sectoral collective bargaining that enables unions to negotiate with industries rather than individual firms, increasing organized labor’s power to lift wages, set industrywide standards, and reach agreements that benefit a greater number of workers

- Laws that expand and protect workers’ right to engage in collective action, including the creation of funds that allow workers to engage in strikes or walkouts without jeopardizing their financial security

- An inclusive labor law reform that places the need to address gender, racial, and ethnic inequities at its center by extending protections to domestic, incarcerated, and undocumented workers, as well as expanding rights and protections for independent contractors

Other proposals include:

- The creation of labor market institutions such as wage boards, which set minimum pay standards by industry and occupation, and lead to wage gains for those at the bottom and middle of the income distribution

- Passing legislation such as the PRO Act, which would make it easier for workers to organize into unions, and would also curtail employers’ ability to misclassify workers as independent contractors, who do not have the right to unionize under federal U.S. law

These measures would expand workers’ rights and allow unions to balance power in the labor market, ensuring that the economic gains they create are broadly shared.