Extensive nonstandard work hours among U.S. low-income mothers hinder their kids’ enrollment in center-based childcare

Significant income-based disparities in kids’ enrollment in center-based early childcare and education persist in the United States. Two well-documented reasons are the high costs of this kind of care and the limited availability of childcare slots. Now, a group of researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison find there is a third factor that explains these disparities—low-income parents are more likely to work nonstandard schedules, including early morning, evening, overnight, and weekend hours, than their higher-income peers, which particularly constrains their ability to make arrangements for center-based early childcare and education.

Alejandra Ros Pilarz, Ying-Chun Lin, and Katherine A. Magnuson delve into this issue in their new study published in Social Service Review. They specifically examined whether mothers’ work hours and schedules explain income-based disparities in enrollment in center-based care between low- and high-income families. Using data from the National Survey of Early Care and Education, they find that the number of hours a mother works and whether she has a standard schedule are predictive of the childcare arrangements she uses. What’s more, they find that significant portions of the disparity in enrollment in center-based care between low- and high-income families can be explained by low-income mothers working fewer total hours and more nonstandard hours.

Concerns over disparities in center-based care and education are twofold. First, there is increasing evidence that when children attend center-based care, they enter school academically and socially ahead of their peers who did not attend, especially among low-income children. Secondly, research shows that center-based childcare better supports parents and the U.S. economy. The reason: Home-based care is both less reliable and more temporary than center-based care. Unexpected unavailability is more likely to come from a grandmother’s hospitalization, for example, than cancelation from a licensed day care center. Consequently, studies show that greater work absences caused by unstable home-based childcare are associated with mothers eventually leaving their jobs. So, it’s not surprising that center-based early childcare and education programs improve parents’ productivity, prospects for professional advancement, and ability to provide economic security, compared to home-based care.

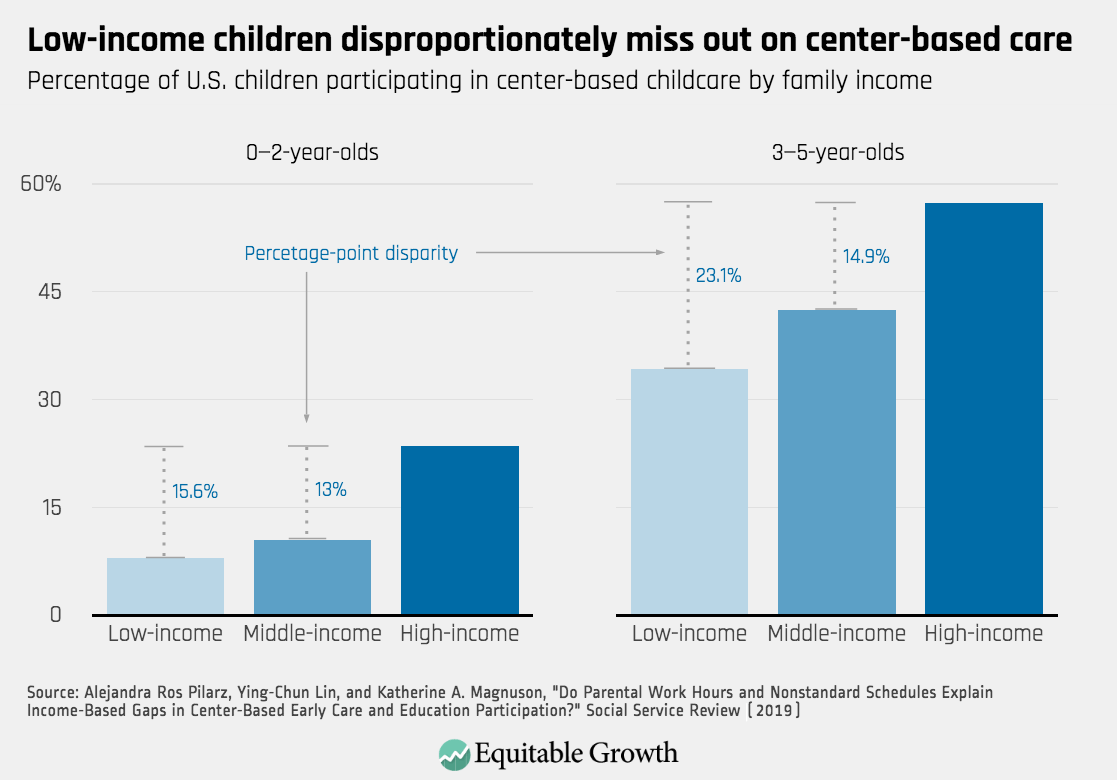

Unfortunately, while center-based early childcare and education is important to all children, many miss out on its benefits. In their research, Pilarz, Lin, and Magnuson find that high-income households with children ages 0 to 2 are 15.6 percentage points more likely to enroll in center-based care than comparable low-income families. The gap is even larger for families with children ages 3 to 5: 23.1 percentage points. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

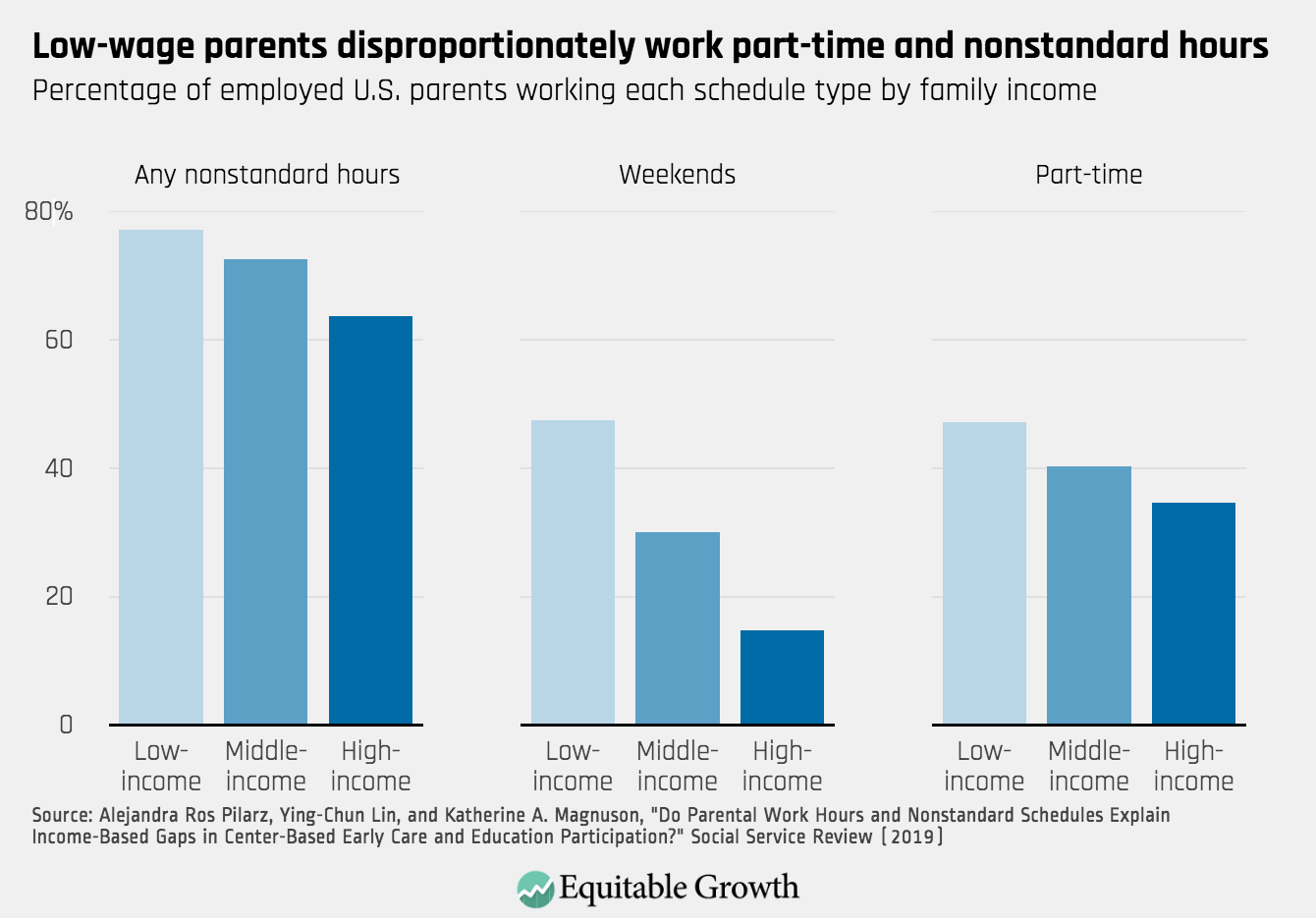

At the same time, low-wage parents are more likely to work nonstandard hours and fewer hours than they would like. Past research shows that low-wage workers are also significantly less likely to have control over their work schedules. Together, the research indicates that low-wage workers are forced to accept difficult and demanding schedules due to economic need. In line with the results of previous studies, the three University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers find significant differences in mothers’ work schedules by family income. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

These disparities raise a question: Do nonstandard work schedules limit low-income parents’ ability to enroll their children in center-based early childcare and education programs? If so, it may be the case that while these parents suffer from difficult work weeks, their children suffer from lower-quality care. In this way, economic hardships faced by low-income parents limit opportunities for younger generations within families, exacerbating income-based disparities in well-being and intergenerational mobility.

Currently, the existing literature suggests that several variables, including family demographics, household composition, and neighborhood characteristics, as well as childcare costs and availability, are strong predictors of childcare arrangements. Controlling for these factors, Pilarz, Lin, and Magnuson examine whether mothers’ work hours and schedules are predictive of childcare decisions and explain income-based disparities in enrollment in center-based care and education programs.

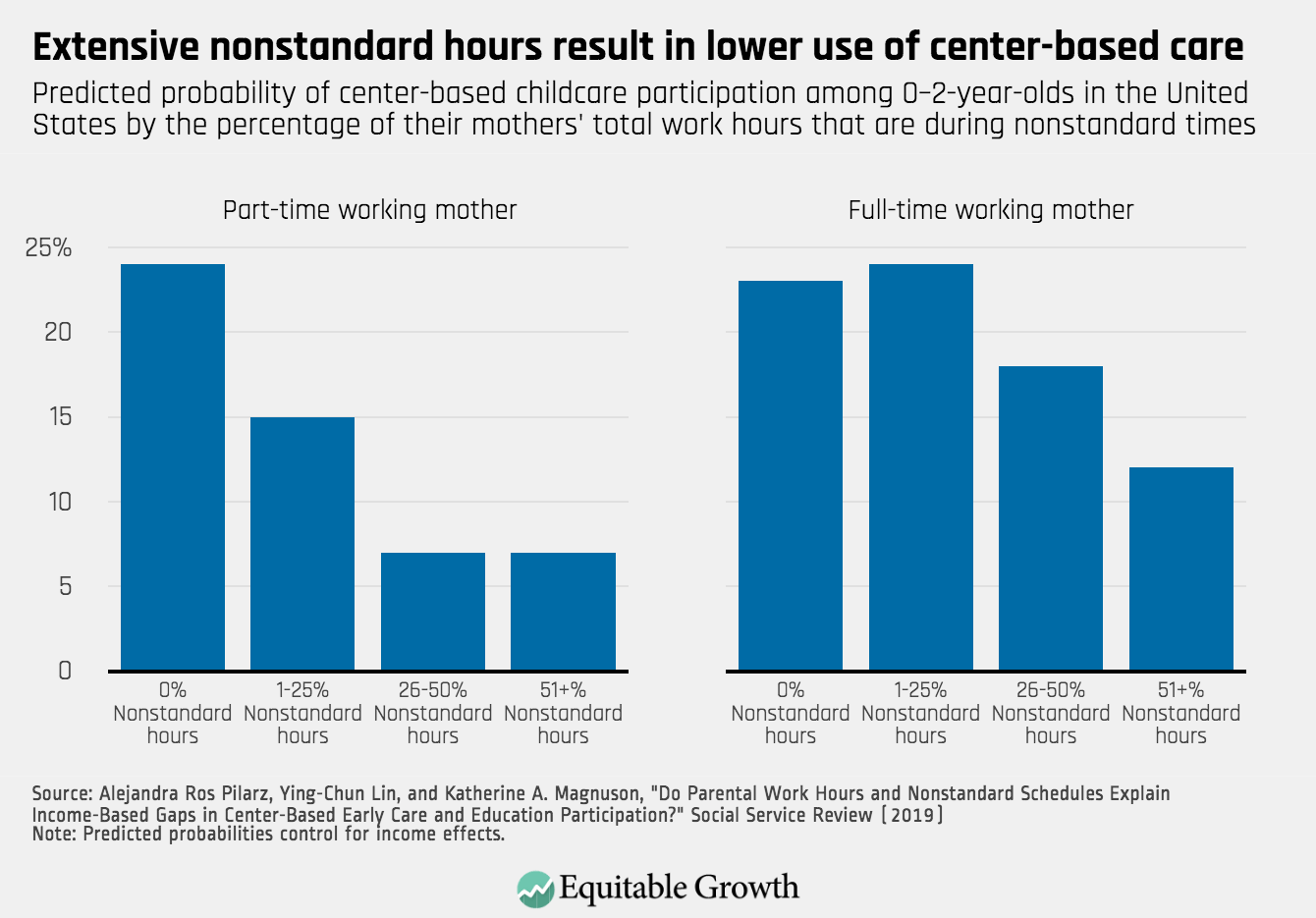

Perhaps their most compelling findings relate to children ages 0 to 2. Center-based care arrangements for children in this age range are comparatively scarce, and the research base on care arrangements for infants and toddlers is thin. Accordingly, looking at the mothers of infants and toddlers, the University of Wisconsin-Madison research team finds that even after accounting for income, mothers who work fewer total hours, more nonstandard hours, and/or a greater extent of their total hours during nonstandard times have significantly lower predicted probabilities of using center-based care. This means that while low-income mothers as a whole are disproportionately left out of center-based care simply due to financial constraints, those who work nonstandard schedules are even further disadvantaged. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Nearly one-quarter of mothers who are part-time workers but do not work any nonstandard hours (the bar labeled 0 percent in Figure 3) place their children who are younger than 2 in center-based care. Part-time working mothers who work between 1 percent and 25 percent of their total hours during nonstandard times are less likely to place their children in center-based care—only 15 percent do so, and the proportion plummets further for part-time working mothers who work more than one-quarter of their hours during nonstandard times. For full-time workers, a similar declining trend emerges once mothers work more than one-quarter of their hours during nonstandard times.

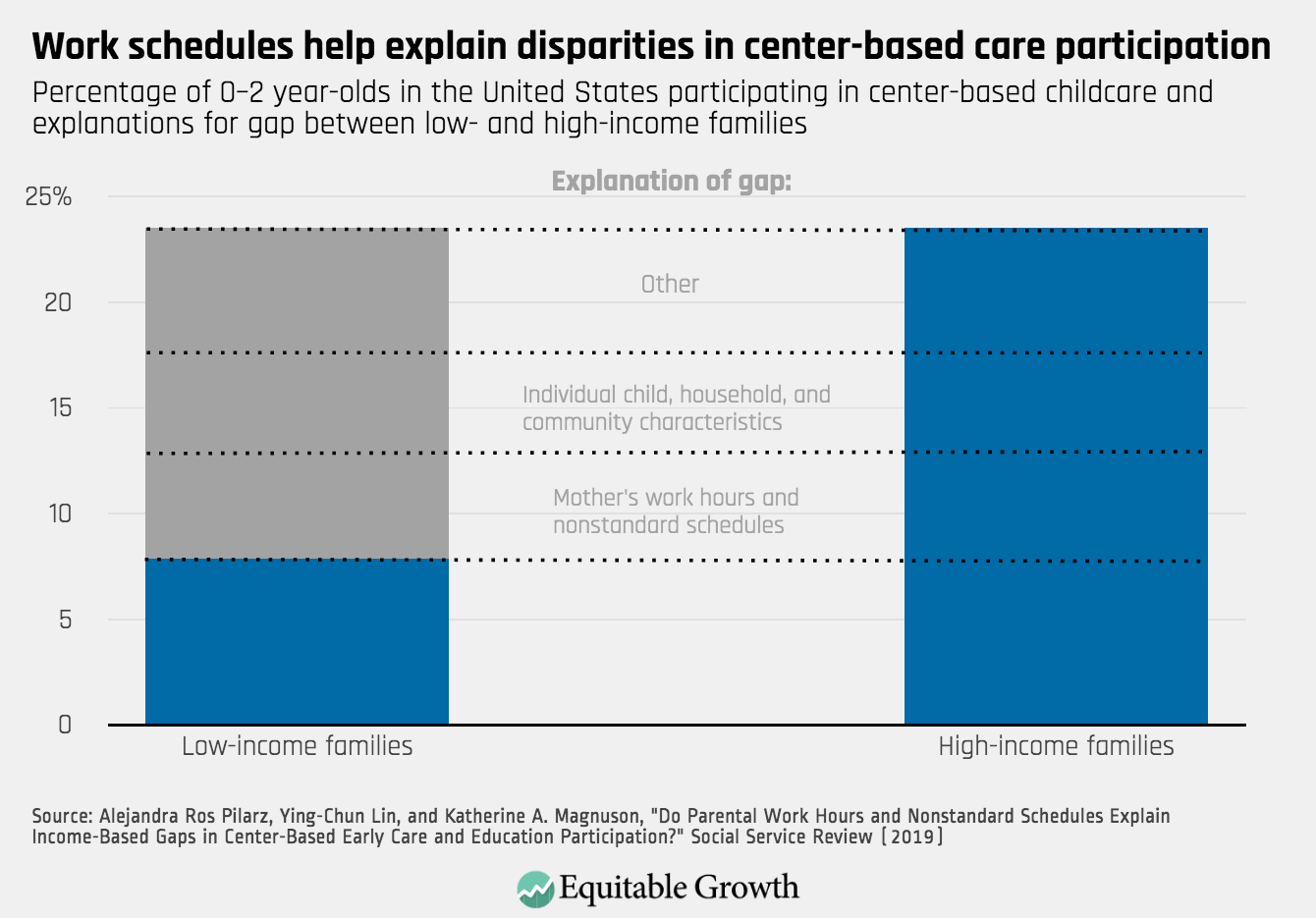

Pilarz and her co-authors conclude that mothers’ work hours and schedules explain about one-third of the 15.6 percentage-point gap in center-based early childcare and education enrollment between low- and high-income families with children ages 0 to 2. For comparison, another one-third of the disparity can be explained by the combination of all of the controls used in the study. This means that mother’s work schedules explain as much about the disparity in access to center-based childcare as children’s personal and demographic characteristics, parent’s education and professional training, household size and employment, geographic location, and neighborhood poverty concentration combined. (See Figure 4).

Figure 4

The clear implication of these findings is that addressing income-based disparities in work schedules could increase the rate of enrollment in center-based early childcare and education among low-income families. This can be done by implementing fair work scheduling laws that strengthen low-wage workers’ control over their work hours and schedules. Such an approach would expand parents’ ability to access center-based childcare programs by minimizing underemployment and increasing the proportion of hours worked during standard times.

Specifically, so-called access-to-hours provisions can increase total hours worked and incomes by requiring employers to offer additional available hours to part-time workers before hiring additional employees. Furthermore, “right-to-request” provisions can reduce the percentage of hours worked during nonstandard times by protecting employees who request specific schedule arrangements from employer retaliation. The new research by Pilarz, Lin, and Magnuson suggests that these provisions, which empower working parents and incentivize low-wage employers to accommodate their employees’ family needs, could reduce disparities in center-based childcare enrollment between low- and high-income families.

States and localities have increasingly adopted such provisions. But despite progress in this policy area, the high consumer demand for a 24/7 service economy will most likely persist. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that low-wage parents will continue to work early morning, evening, overnight, and weekend hours, limiting their ability to enroll in current center-based care programs. Therefore, it may be just as important to increase support for low-income families in which parents work insufficient or nonstandard hours as it is to reduce the prevalence of such schedules.

One way to do this would be to increase access to center-based care during nonstandard hours. The Child Care for Working Families Act addresses this issue. The proposed legislation would incentivize and fund childcare during nontraditional hours of operation, in essence, expanding access to childcare for families who need it outside of the traditional 9:00 a.m.–5:00 p.m. workday. In this way, families who continue to work lower-quality schedules can still benefit from higher-quality childcare.

Future research by these and other researchers, much of which will likely employ more detailed data and precise variables on work-schedule quality, will enable further nuanced and specific interpretations of the effects of nonstandard, unstable, and unpredictable work schedules. Nevertheless, there is substantial evidence now for policymakers to act. Current income-based disparities in work schedules and childcare arrangements are limiting economic security for parents, development for children, and growth for the U.S. economy as a whole. State and local governments throughout the country are already leading the way, using research to inform evidence-based policy solutions. The federal government should follow suit.