Equitable Growth scholars highlight the need for broad investment in U.S. social infrastructure

Our nation’s social infrastructure is composed of the economic and social investments that are necessary for U.S. workers and families to be able to take care of their loved ones and remain productive members of the U.S. workforce. Social infrastructure is an essential support system for workers in the United States that enables the rest of the economy to function. Yet the nation has long underinvested in it. This policy choice leaves workers to fend for themselves in times of health or economic crises. They face impossible choices between their loved ones and their livelihoods, which ripple out to affect the broader economy.

As the debate continues on the size and scope of social infrastructure investments to include in the Build Back Better Act now under negotiation in Congress, Equitable Growth today released a new essay on the need for policymakers on Capitol Hill to boost investments in social infrastructure. The essays, penned by two of the nation’s leading experts on social and economic policy—Liz Ananat of Barnard College and Anna Gassman-Pines of Duke University—is the latest in a series of pieces by Equitable Growth scholars making the case for robust social infrastructure in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

Highlighting an extensive body of research on the benefits of social infrastructure programs for workers and the overall economy, these scholars make a compelling case: For the United States to emerge from the pandemic in a stronger economic position than it entered it, policymakers must make substantial investments in the nation’s social infrastructure. This includes income support for families, U.S. child care and early education systems, home- and community-based services and supports for older adults and people with disabilities, and a comprehensive paid leave program.

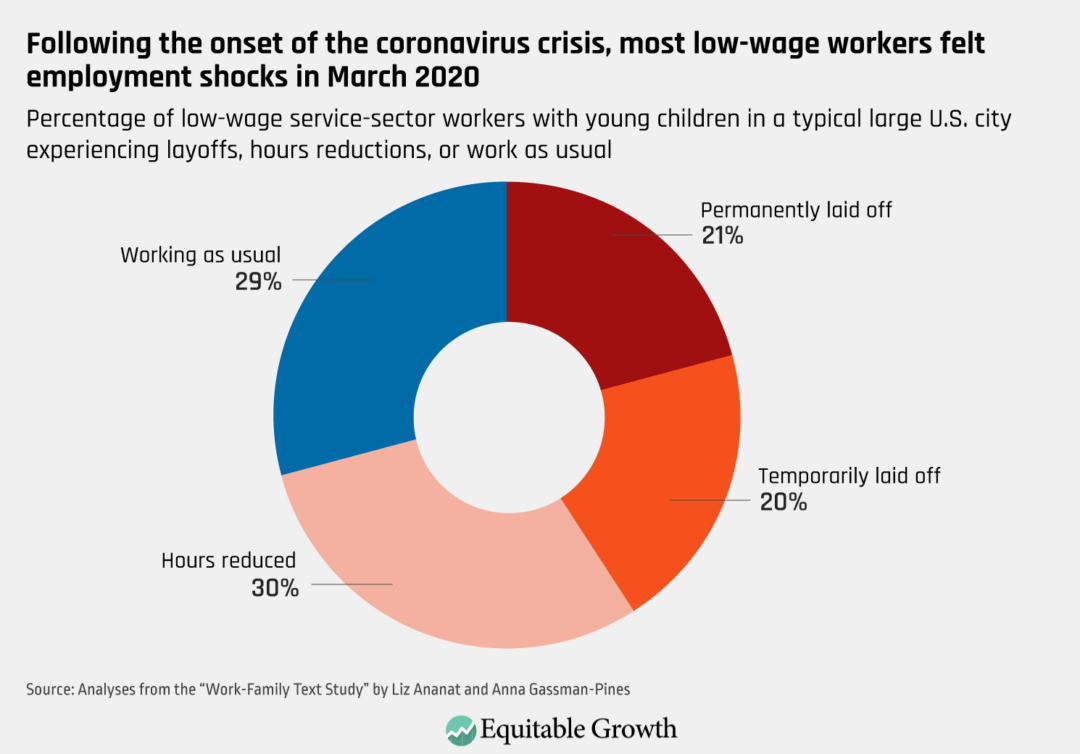

In May 2020, Ananat and Gassman-Pines authored a New York Times op-ed that shared results from their Work-Family Text Study, launched in February 2020. The study collected daily surveys administered by text messages to 1,000 service-sector workers in Pennsylvania who have young children to look at the effects of a stable scheduling ordinance on their well-being. Their results paint a picture of severe employment disruption in March, and “by the end of April,” they wrote, “only 20 percent were working as usual.” (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

In their new Equitable Growth essay, they pick up where they left off, describing the struggles many of these workers reported facing between their work responsibilities and caring for their families. These challenges were especially pervasive amid care disruptions and school and care center closures resulting from the pandemic. Indeed, they write, “1 in 7 of our respondents are responsible for an elderly or disabled loved one, and nearly a quarter of those lost the help they had to care for them,” while 77 percent of respondents had to reshuffle work schedules to care for their children.

Ananat and Gassman-Pines’ work highlights the twin roles of people as workers and as caregivers for family members both old and young. They note that “our economy will be stronger and our families will be more secure tomorrow if we invest in care today,” and also point to an existing policy success to build on: After Congress enhanced the Child Tax Credit earlier this year, food security was cut in half among receiving families.

Our economy will be stronger and our families will be more secure tomorrow if we invest in care today.

Liz Ananat and Anna Gassman-Pines

Investment in child care and early education is a crucial piece of investment in care as well. In an op-ed piece in New Hampshire’s Union Leader, Dartmouth College’s Kristin Smith notes that“child care providers are among the lowest-paid workers in the United States. Individuals in paid care jobs earn less than other workers with similar credentials, characteristics, and demographics.” Yet this work makes so much other work possible. Smith writes that “when 860,000 women left the labor force in September 2020, the essential role that teachers and child care providers play in supporting women’s labor force participation became indisputable.”

It’s not just U.S. child care infrastructure that needs investment. As economist Yulya Truskinovsky at Wayne State University notes in her June 2021 Detroit News op-ed, caregiving arrangements for older adults and people with disabilities “were precarious even before the pandemic. Turnover among direct care professionals was high due to low wages and poor job conditions, including high rates of workplace injury.”

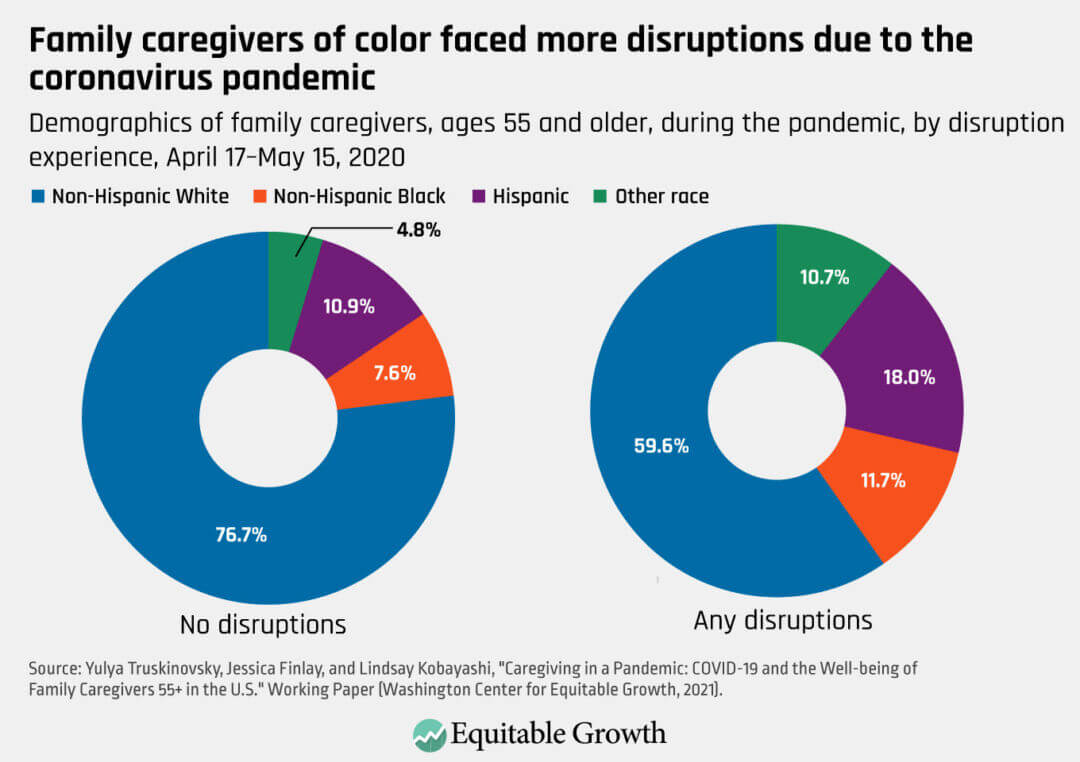

In a related Equitable Growth column summarizing her working paper with Jessica Finlay and Lindsay Koyabashi of the University of Michigan, Truskinovsky notes that disruptions to fragile caregiving arrangements were prevalent during the pandemic and that “those caregivers who provided more care because of the pandemic—disproportionately women and people of color—were almost 19 percentage points more likely than noncaregivers to report an impact on their employment.” (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Truskinovsky calls for a federal paid leave program, which would provide up to 12 weeks of paid leave for workers who need time off to care for a loved one with a serious medical condition. She also proposes improvements in improving pay and working conditions for professional caregivers, who provide community-based services and supports to people with serious medical needs year round. Both are essential to ensure that older adults and people with disabilities get the support they need and that their loved ones can fully participate in the paid labor force.

Three other Equitable Growth scholars have also weighed in on the importance of paid leave in the pages of U.S. newspapers. In her op-ed in the Union Leader, Dartmouth College’s Smith writes, “My research shows that nearly 80 percent of New Hampshire residents support a paid family and medical leave insurance program, though such a program does not exist—yet.”

In the pages of the Portland News, Julia Goodman of Portland State University and Danny Schneider of Harvard University describe their fall 2020 survey of 8,500 workers at 125 of the largest service-sector firms in the nation, writing that “Thirteen percent of workers reported they had needed to care for someone else with a serious medical condition. And 4 percent of workers told us they welcomed a new child in the past year. Yet two-thirds of these workers, and nearly 1 in 5 front-line service-sector workers, told us they couldn’t take the leave they needed.” They quote one worker, who explains simply that “We don’t make money if we don’t work. To survive we must work sick!”

Over the past 18 months, it has become ever more clear that U.S. social infrastructure policies form an economic backbone that is just as powerful as the one provided by roads and bridges. But just as there are many components necessary to make physical infrastructure function, social infrastructure cannot work in isolation.

A new parent needs paid leave and child care to stay in the labor force and a monthly payment from the fully refundable Child Tax Credit to keep their children in diapers. A worker whose sibling experiences a traumatic brain injury needs paid leave to make arrangements after the injury occurs and community-based services and supports for their sibling when they return to work. To become a productive participant in the economy, a child needs care in the first years of life, preschool to prepare them for Kindergarten, and funds from the monthly fully refundable Child Tax Credit to ensure that they have the school supplies they need through their teenage years.

Since the early days of the pandemic—and indeed long before the pandemic occurred—these leading scholars have been conducting rigorous research that uncovers the need for a serious investment in the many crucial facets of the nation’s social infrastructure. They provide the evidence that makes the urgency of this moment impossible to ignore.

Though the research they do and the policies they discuss differ, one theme shines through them all: To emerge from this pandemic stronger, the United States needs substantial and bold investment in the people—the workers, families, and caregivers—that drive the U.S. economy.