Coronavirus recession deepens U.S. job losses in April especially among low-wage workers and women

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly Employment Situation Summary for April released today provides new data on the speed and magnitude with which the coronavirus recession is sending ripples through the U.S. labor market. The report shows that the economic shock is affecting every sector of the economy, but workers in low-wage industries, women, and those with a high school degree and some college are experiencing the largest upticks in unemployment.

The coronavirus pandemic and ensuing recession caused the sharpest month-to-month drop in employment since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began collecting data on unemployment in 1948, with the loss of 20.5 million nonfarm payroll jobs from mid-March to mid-April. Over two months, the unemployment rate surged from a 50-year low of 3.5 percent in February to 14.7 percent in April— 4.7 percentage points higher than during the worst months of the Great Recession of 2007-2009. As of April just over half of the U.S. population—51.3 percent—has a job, the lowest share on record.

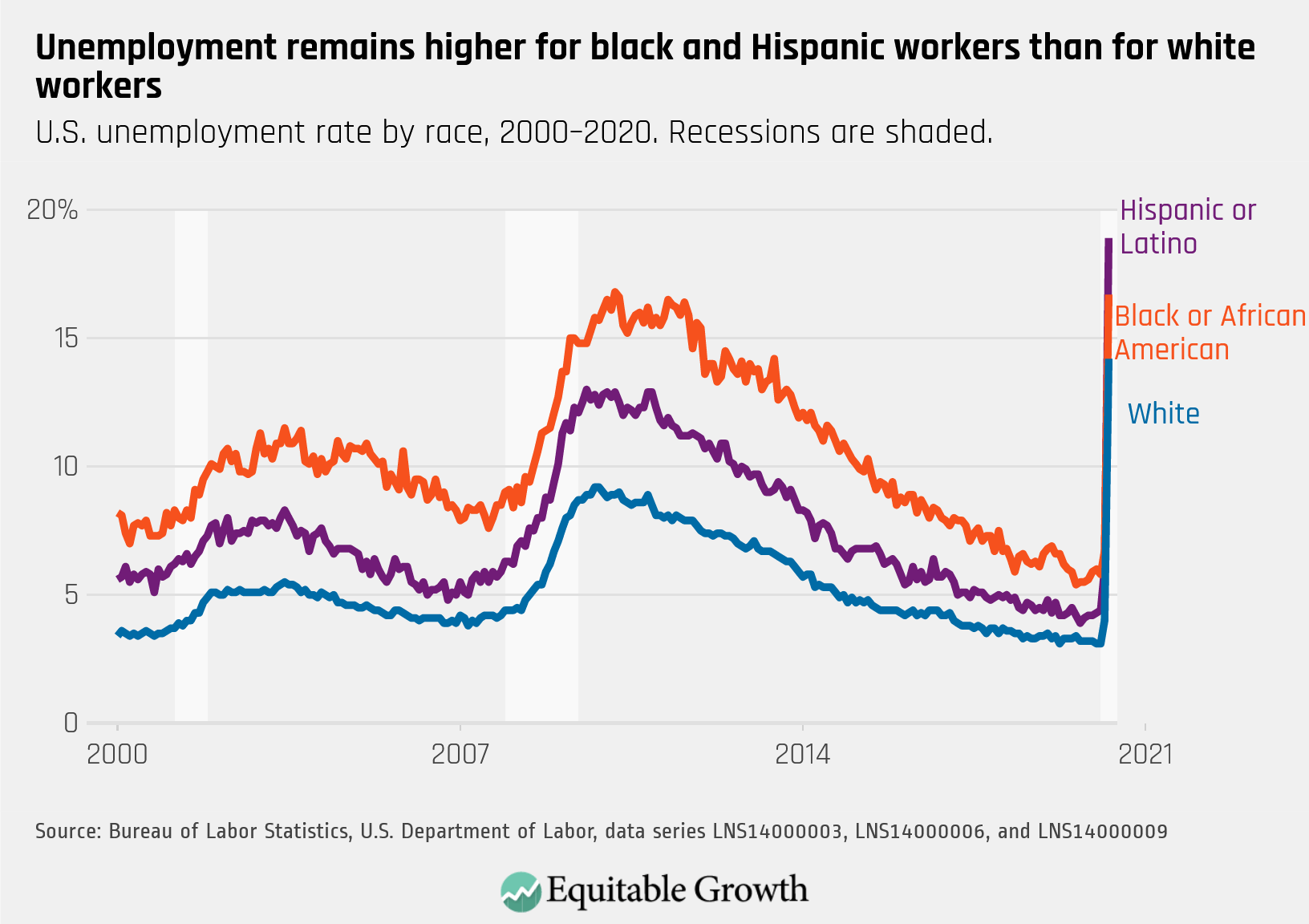

The unemployment rate of Hispanic workers surged to 18.9 percent, an all-time high, while black unemployment rose to a massive 16.7 percent, though this was not a high. Indeed, the usual gap between white and black workers—with blacks typically having an unemployment rate twice that of whites—shrank as many black workers remain employed in essential jobs (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Women also have been disproportionately affected. Compared to the so-called “Mancession,” where male-dominated sectors such as construction were the first to suffer job losses during the early months of the Great Recession, this downturn hit service-sector workers first, leading to a sharp uptick in the unemployment rate for women. The joblessness rate of women workers over the age of 16 increased 268 percent, from 4.4 percent in March to 16.2 percent in April, compared to men’s increasing 206 percent, from 4.4 percent to 13.5 percent.

As the coronavirus pandemic led many businesses to close their doors and caused demand for certain services to plummet, workers’ ability to work from home emerged as an important first line of defense against both economic insecurity and health risks. Mining and utilities lost the fewest jobs, in no small part due to the essential nature of those jobs. Second in terms of fewer job losses, however, were the information and financial services industries—which have some of the highest paying jobs in the U.S. economy and where the greatest share of workers can typically work from home.

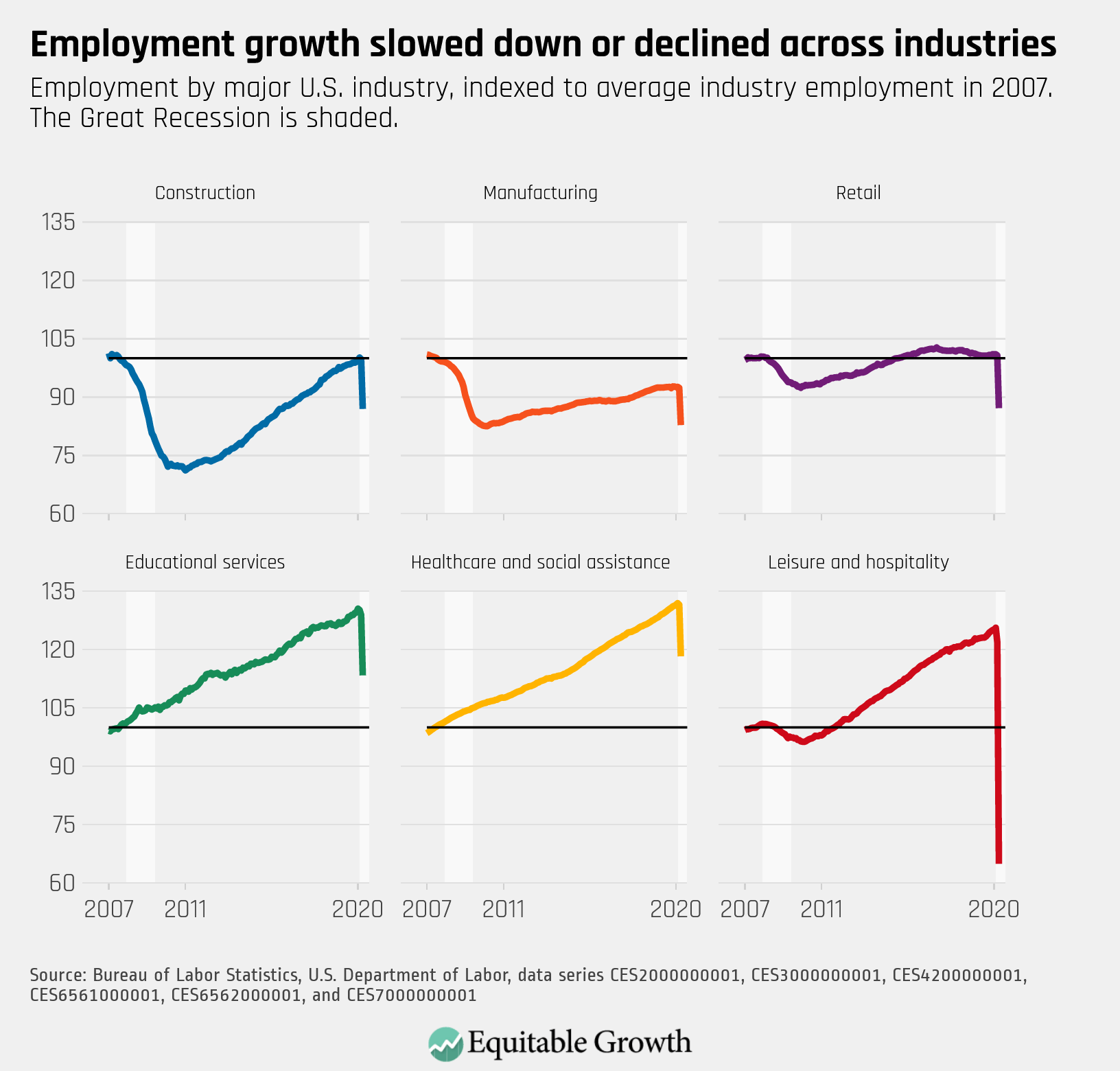

In contrast, many of the workers most affected by the swift economic downturn hold jobs that are not classified as essential and cannot be done from home. This month about 90 percent of job losses happened in sectors where less than one in five workers reported in a survey conducted between 2017 and 2018 that they have the option to telecommute. It is likely that this measure somewhat misrepresents the number of workers who have been able to work from home since the onset of the pandemic. Even so, with 7.7 million jobs lost in the leisure and hospitality industry alone, which makes up nearly half of all the jobs in that sector, jobs where workers previously rarely had the option to telecommute accounted for more than a third of this last month’s economy-wide decline in employment.

The same survey reports that 29 percent of workers said they have the option to telecommute, yet only 8.8 percent of leisure and hospitality workers—cooks, musicians, housekeepers, restaurant staff and managers—have the ability to do so. The next hardest-hit industries were education and health services and retail, with the loss of 2.5 million and 2.1 million jobs, respectively. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Disparities in workers’ ability to telecommute are both reflecting and exacerbating existing inequities in the U.S. economy. Higher-wage workers, those with higher levels of education, and white and Asian workers are more likely to hold jobs that allow them to work from home. In tandem with low-wage industries currently experiencing the greatest losses in employment, this means that the workers most likely to lose their jobs or have their pay cut are also the least likely to have the financial cushion to withstand a loss of income. This is evident in the data on weekly earnings, which shows a sharp uptick, indicating that the composition of the U.S. labor force has shifted toward workers with higher pay as those with less pay were disproportionately let go.

With average hourly earnings of $18.00 and $21.20, respectively, the hospitality and retail industries are the lowest paying industries in the United States. They also tend to be particularly precarious jobs, falling behind most sectors in terms of access to worker protections such as paid sick and family leave.

But the effects of the current recession are not limited to low-wage service sectors, and workers with the ability to telecommute are not immune to unemployment. Even as states and cities start to relax social-distancing measures, restaurants, hotels, and stores will not be operating at full-capacity in the immediate future. While not as massive as the job losses in hospitality and leisure, professional and business services—a relatively high-wage sector where more than 50 percent of workers can telecommute—lost 2.1 million jobs between mid-March and mid-April.

The current unemployment crisis already has either wiped out or led to the furloughing of the equivalent of the total number of jobs created over the past decade. The eventual economic recovery from this recession will be both quicker and more complete if policymakers act swiftly to protect the most vulnerable workers.

To do so, they should expand access to the additional $600 of unemployment insurance benefits beyond July 31, the timeline currently stipulated under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES Act. Similarly, short-time compensation, or work-sharing programs, would help but the breaks on job losses and make an economic recovery easier on both workers and employers.

The coronavirus recession lays bare the ways in which the prevalence of low-wage jobs with little access to benefits has made our labor market fragile in the face of downturns. Essential positions in healthcare, grocery store and food production, and delivery and warehousing, are all critical to maintaining our well-being. These jobs should receive so-called heroes pay, where a separate fund bolsters wages for essential workers. Workers also should get a say in their own workplace safety standards through the institution of workplace councils. Unions, too, should play a role in supplementing the enforcement of mandated safety protocols. These measures protect workers who are not able to work remotely so that all of society can cope with the dual public health and economic crises.