Coronavirus disruptions in family caregiving highlight the importance of investments in U.S. care infrastructure and paid leave

Most workers in the United States at some point over the course of their lives will take on multiple unpaid caregiving responsibilities, be it caring for a child, an elderly parent, or an ailing relative. This can be highly rewarding and meaningful work, but it also can be incredibly challenging, particularly for those trying to balance these responsibilities with paid work.

The coronavirus pandemic highlights anew some of these work-life challenges, particularly as relates to working parents, especially mothers, who have had to piece together child care arrangements in the midst of school and day care closures or leave the labor force altogether. But much less is known about how the pandemic affects other family care arrangements or the consequences of these disruptions on caregivers’ mental health and employment status.

A working paper I co-authored earlier this year with Jessica Finlay and Lindsay Kobayashi of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor explores this less-studied area of caregiving amid the pandemic. We look at how family caregivers ages 55 and older dealt with sudden disruptions in caregiving arrangements due to the coronavirus and COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus, in the in the spring of 2020.

Family caregivers are those people who provide care for a spouse, elderly parent, or other relative with a long-term illness or disability, as well as grandparents who care for their grandchildren and those providing unpaid care to recipients without a formal kinship relationship, such as a friend or a neighbor. Family caregiving typically does not include parents caring for their own children. We decided to study those ages 55 and up because this group typically provides family caregiving while also facing age-based elevated risks for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.

Using data collected between April 17 and May 15, 2020 from the COVID-19 Coping Survey, an online questionnaire, our study measures the mental health and employment outcomes for a national sample of around 2,500 respondents, of whom 535—or more than 1 in 5—were family caregivers. We find that the coronavirus pandemic disrupted more than half of family caregiving arrangements, with more than 30 percent of caregivers reporting additional or new care responsibilities as a result of the crisis. Another 20 percent of caregivers reported that they were providing less care than usual, likely due to social distancing measures and concerns about their health or the health of their loved ones.

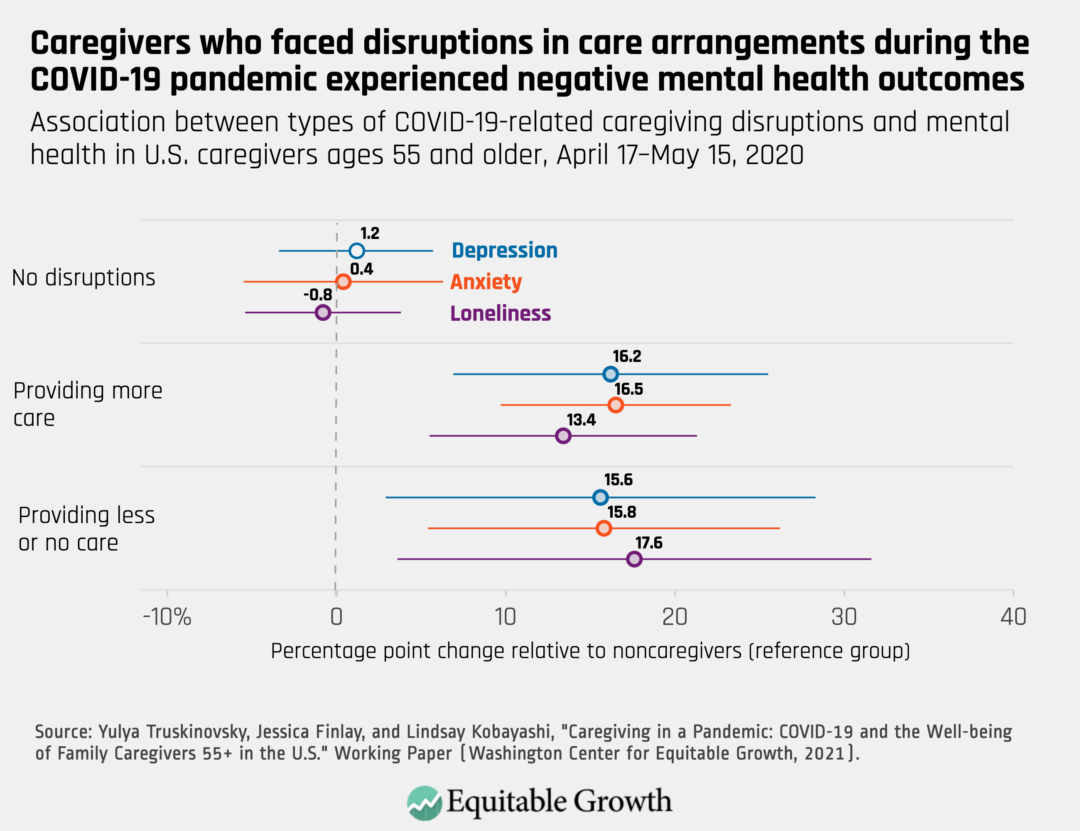

Troublingly, we also find that these disruptions were associated with negative mental health outcomes, such as increased depression, anxiety, and loneliness. Those respondents whose care arrangements were disrupted were 18.1 percentage points more likely to screen positive for depression, 19.5 percentage points more likely to screen positive for anxiety, and 16.1 percentage points more likely to screen positive for loneliness than either noncaregivers or those caregivers who did not face similar disruptions. Notably, mental health outcomes vary only slightly depending on whether disruptions resulted in caregivers providing more care than usual, or no care or less care than usual. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Caregivers who experienced disruptions due to COVID-19 were not only more likely to report negative mental health effects but also 13.9 percentage points more likely to report employment disruptions. And those caregivers who provided more care because of the pandemic—disproportionately women and people of color—were almost 19 percentage points more likely than noncaregivers to report an impact on their employment, typically in the form of a job loss, furlough, or transition to working from home.

These findings confirm research that highlights the importance of investments in care infrastructure, not just for caregivers and their loved ones but also for the broader U.S. economy. Our research also emphasizes the need for policymakers to finally enact a nationwide paid leave program.

Turnover in the professional caregiving industry has long been high due to low wages and poor working conditions, a trend that the coronavirus pandemic has not curbed. These workers—whose daily efforts make it possible for the rest of us to do our jobs effectively and for our loved ones to live with dignity and grace—should be compensated at a level that is commensurate with the contributions they make to the economy.

Investing in the care economy to make these jobs attractive and well-paid would help workers who have left the labor force due to caregiving responsibilities over the course of the pandemic go back to work and would boost worker productivity. These actions would reverberate across the U.S. economy, bolstering the economic and labor market recovery from the coronavirus recession.

But more must be done. Given the piecemeal structure of the U.S. long-term care system, caregiving routines will always be subject to disruptions, meaning working family members are likely to require time off from their jobs to cover their loved ones’ care needs as new arrangements are made. A nationwide paid leave policy would ensure that workers do not have to make the impossible choice between caring for their ill family members and paying their bills or putting food on the table. As of now, only six states and the District of Columbia have paid leave policies for workers needing to care for ailing family members. These policies must be extended nationally to cover all family caregiving needs and situations.

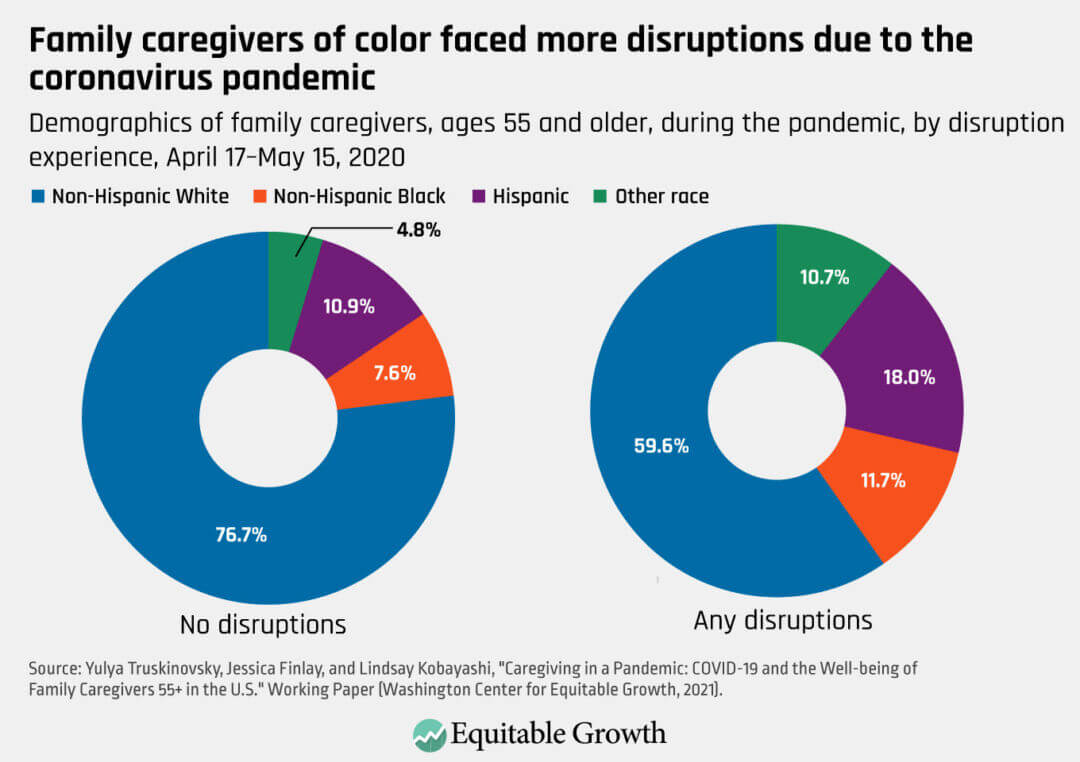

Expanding paid leave also would work to address some of the racial and gender inequalities that arise as a result of caregiving responsibilities. Our study shows that caregivers who were more vulnerable to disruptions were disproportionately female, Black, and Hispanic, and that those who experienced disruptions were more likely to report negative mental health and employment outcomes. These trends were not brought about by the pandemic but have nevertheless been exacerbated in its wake. Policymakers cannot allow these inequalities to fester or worsen. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

As the U.S. population ages, family caregivers will increasingly play a central role in the national healthcare system. And while it is still too early to know for sure, the chaos and heartbreaking scenes of sickness and death in nursing homes over the past year may induce even more families to choose home- and community-based care for their loved ones.

These trends mean that good working conditions for professional caregivers and programs such as paid leave for all workers are all the more essential. Now is the time for policymakers to ensure these vital players in the U.S. economy and labor market have the support and infrastructure they need to take care of themselves and balance their caregiving responsibilities with their jobs. The benefits will extend beyond those directly impacted to the broader economy.