Congress needs distribution analyses to make informed, equitable policy choices, and the CBO FAIR Scoring Act would deliver it

Before voting on legislation, members of Congress usually receive a cost estimate, or score, for that legislation from the Congressional Budget Office. This score provides nonpartisan CBO analysts’ best estimate of how the legislation will affect the federal budget deficit.

A cost estimate is useful information for legislators, but it represents only one side of the equation. Costs are incurred to deliver benefits, yet members of Congress rarely receive analysis to assess who will benefit from bills and by how much. Currently, without any requirement for this type of analysis, members of Congress all too often must vote on legislation with formal analysis of the costs but with only informal or no analysis of the benefits.

Today, Reps. Ro Khanna (D-CA) and Dean Phillips (D-MN) in the U.S. House of Representatives and Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) in the Senate introduced the CBO FAIR Scoring Act. The proposed law would represent a major step forward for the legislative process by directing the Congressional Budget Office to prepare distribution analyses by race and income for all legislation with substantial budgetary effects. In short, these analyses would provide members of Congress with CBO analysts’ best estimate of how the legislation would affect different groups of people—critical information for evaluating who would benefit. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

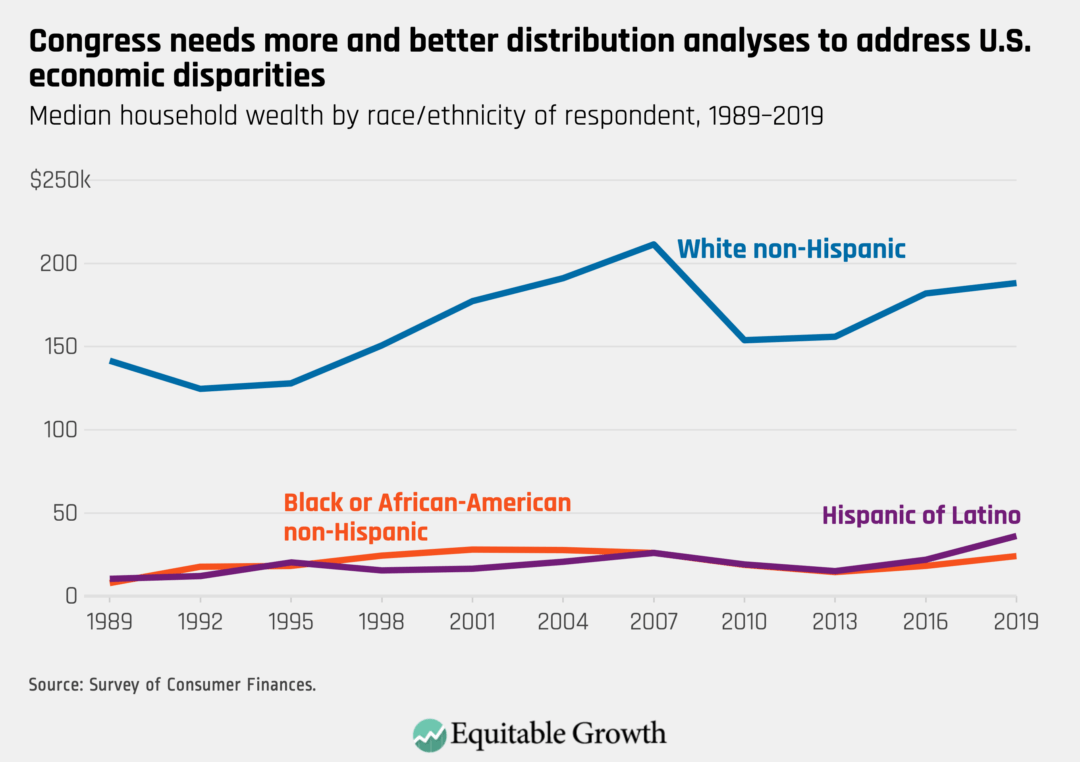

The need for a better understanding of how legislation would affect different groups of people is apparent in the high levels of inequality in the United States. In 2019, prior to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the median wealth of White families was $188,200, while the median wealth of Black families was only $24,100 and the median wealth of Hispanic families only $36,100. Families in the top 1 percent of the income distribution accounted for 20 percent of income, and families in the top 1 percent of the wealth distribution accounted for 33 percent of all wealth.

The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated, and was itself exacerbated by, these disparities. Job losses, for example, were concentrated among lower-wage workers. Unemployment rates for Black workers and for Hispanic workers remain consistently higher than unemployment rates for White workers since the onset of the pandemic more than a year ago.

If enacted, the CBO FAIR Scoring Act would ensure that members of Congress receive the distribution analyses they need to make informed policy choices in light of these economic disparities. It would clarify which bills would reduce economic disparities and which bills would increase them. And it would serve as an independent check on policymakers’ sometimes-inaccurate claims about who their policies would benefit.

Specific instances where distribution analysis would be useful in legislation

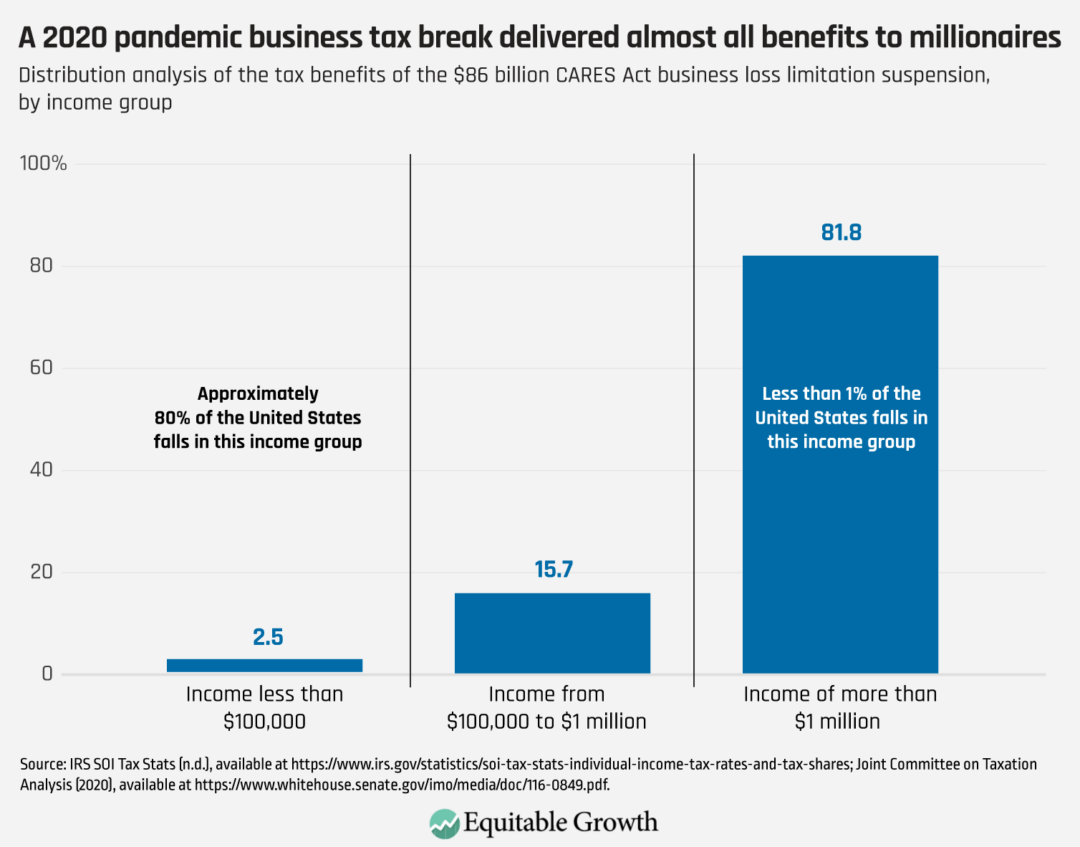

The laws that Congress already passed in response to the ongoing pandemic highlight the importance of this requirement. When the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES, Act, passed in March 2020, the Congressional Budget Office estimated its cost at $1.7 trillion and produced subsequent reports of the detailed breakdowns of those costs by program. But where did the money go? Who benefited from this legislation? The Congressional Budget Office has not answered that question in a comprehensive fashion.

In a notable exception, however, the Joint Committee on Taxation produced a distribution analysis of a single provision of the law—a relaxation of limits on the tax deductibility of certain business losses. The analysis’ finding that this provision delivered significant financial benefits almost exclusively to the richest Americans drew substantial attention and confirmed the interest in distribution analysis among legislators and the public. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Congress frequently revises legislation because of CBO cost estimates or designs bills to fit certain spending goals with CBO estimates in mind. With more frequent distribution analyses, Congress could also fine-tune legislation in response to the distribution analyses. Congress may want to revise a bill if an official CBO analysis shows that it would widen racial income gaps, or if almost all benefits accrue to the rich, as in the above example.

For instance, President Joe Biden and Senate Democrats are currently proposing a bill that will include massive investments in the U.S. economy, but media coverage of the bill overwhelmingly focuses on its costs, rather than its contents and benefits. The bill will include an extension of the recently enacted Child Tax Credit expansion, or child allowance, which delivers monthly checks of $250 to $300 per child to most families in the United States. Outside analyses show this will lower child poverty by nearly 50 percent, but Congress’ official scorekeeper may only analyze the costs of the bill, not its benefits, depriving Congress of crucial information before they vote.

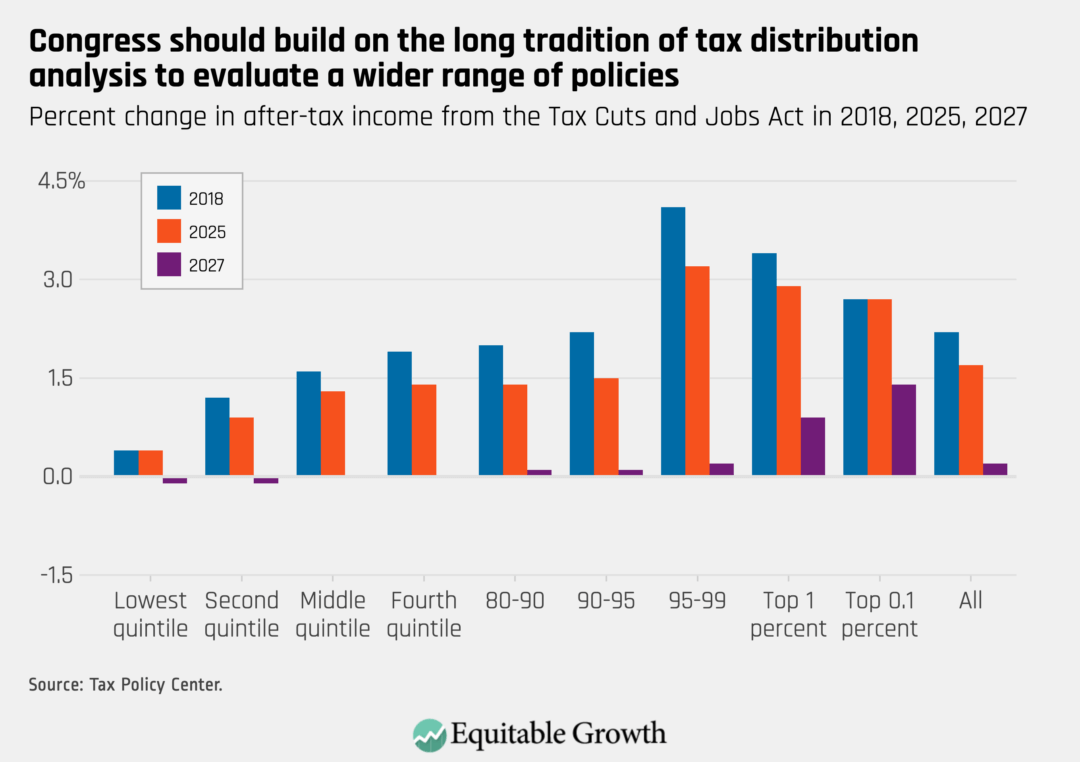

A requirement that the Congressional Budget Office conduct distribution analyses of all legislation with substantial budgetary effects would build on existing informal practice. Currently, distribution analyses are conducted only on a discretionary basis by the Congressional Budget Office and the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. The most common application is for tax legislation. Indeed, the JCT provided Congress with a set of distribution analyses by income during consideration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017, and think tanks such as the Tax Policy Center regularly produce distribution analyses for tax proposals. (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Yet there is no requirement that distribution analyses be provided—and the lack of such a requirement is apparent in the inconsistency with which they are produced. The Congressional Budget Office prepared revised cost estimates for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in April 2018, for example, but it did not prepare revised distribution analyses when it did so.

Moreover, there is no tradition of providing distribution analyses by race by either the Congressional Budget Office or the Joint Committee on Taxation. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, together with Prosperity Now, produced a distribution analysis by race for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, but no similar analysis has been produced by official scorekeepers.

Distribution analysis in academia

There is a long tradition of conducting distribution analysis in the tax context, yet it is underused in other contexts. Application of a distributional logic to these programs is on the rise in academic work, however. Recent research by economists Nathan Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser at Harvard University applied the same economic logic that underlies tax distribution analyses to a range of spending programs, from education and training programs to Unemployment Insurance—exactly the kinds of areas that rarely benefit from this lens in the policy process.

This recent academic research not only uses the techniques of distribution analysis to examine policy impacts for a wider array of programs, but also further clarifies why such analyses should be centered in the consideration of public policies.

The impact of legislation on the federal budget deficit can be measured in dollars and cents, but there is no single measure that captures the impact on all people affected. This academic work by Hendren and Sprung-Keyser highlights that the direct impact on people and families is an accurate measure of how it affects their well-being. Hendren’s prior work lays out in detail why these direct impacts answer this question. And Greg Leiserson, formerly of Equitable Growth, has formalized a similar logic in the specific case of the distribution analysis of tax legislation.

With policy impacts on people and families in hand, analysts must make choices about how to group and compare those impacts to illustrate what the legislation does in a more accessible way. And it is in that step where the need for a distributional perspective comes in.

The distribution analyses produced by the Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation in the past focused on different impacts by income, but the CBO FAIR Scoring Act requires distribution analyses both by income and by race. Thus, the analyses will not just report how legislation affects those at different income levels, but also how it affects Black families and families of Hispanic origin.

This aspect of the legislative proposal builds on prior research by Mehrsa Baradaran, a professor at University of California, Irvine School of Law, that proposes directing the Congressional Budget Office to assess how proposals would affect the racial wealth gap. And recent commentary from Andre Perry at The Brookings Institution and Darrick Hamilton, the director of the Institute for the Study of Race, Stratification and Political Economy at the New School, similarly argues that the White House Office of Management and Budget should develop a means for scoring proposals for racial equity.

Better information will deliver better results

Many inequalities in the United States are the result of policy choices. Just as we need to track who benefits from economic growth economywide—a measure Equitable Growth calls GDP 2.0—lawmakers need to be able to track who benefits from specific legislation they pass.

Public policies can exacerbate economic inequality, and they can reduce it, too. If members of Congress are to enact policies that foster broad-based growth rather than policies that deliver increased poverty and unequal growth, then it is essential that they receive analysis of the distributional impact of policies during the legislative process when it can inform their decision-making. Reps. Khanna and Phillips’ and Sens. Warren and Bennet’s CBO FAIR Scoring Act would require exactly that and would thus represent a dramatic improvement in the legislative process.