Competitive Edge: The states’ view of vertical merger guidelines in U.S. antitrust enforcement

Antitrust and competition issues are receiving renewed interest, and for good reason. So far, the discussion has occurred at a high level of generality. To address important specific antitrust enforcement and competition issues, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has launched this blog, which we call “Competitive Edge.” This series features leading experts in antitrust enforcement on a broad range of topics: potential areas for antitrust enforcement, concerns about existing doctrine, practical realities enforcers face, proposals for reform, and broader policies to promote competition. Phil Weiser has authored this contribution.

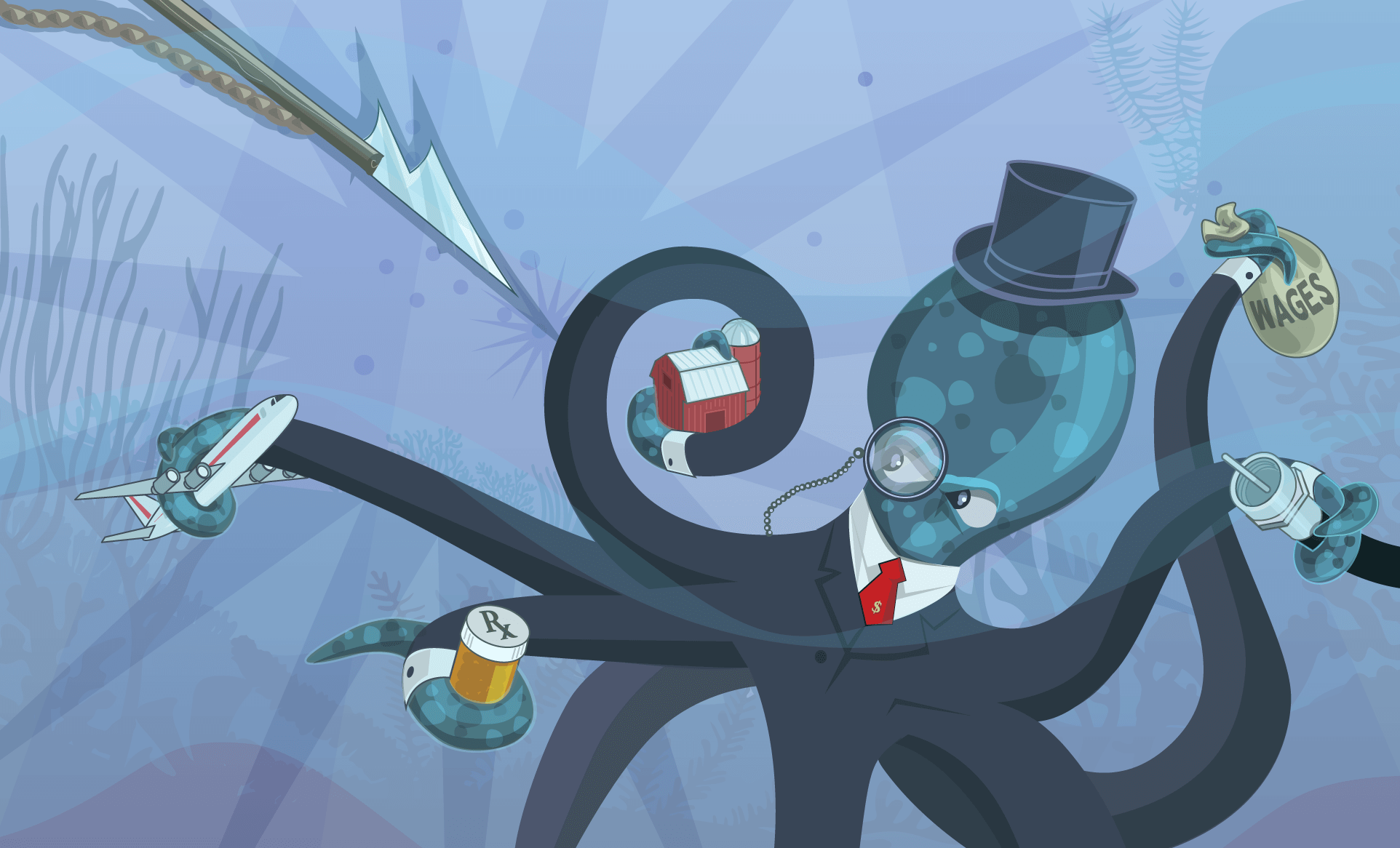

The octopus image, above, updates an iconic editorial cartoon first published in 1904 in the magazine Puck to portray the Standard Oil monopoly. Please note the harpoon. Our goal for Competitive Edge is to promote the development of sharp and effective tools to increase competition in the United States economy.

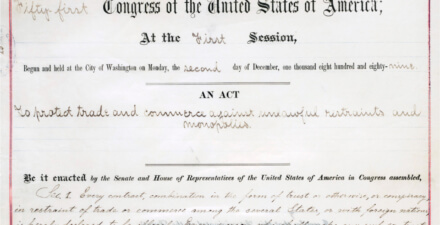

Colorado and 26 other states filed comments today with the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission on their proposed Vertical Merger Guidelines. These two federal antitrust enforcement agencies are commendably working to update an outdated set of guidelines from 1984 that downplay the risks posed by vertical mergers—mergers between companies at different levels of the chain or production, distribution, or marketing of products or services. In our comments, we highlight areas of competitive harm that warrant attention, areas for improvement in these guidelines, and a suggested added focus on remedies.

In so doing, as I have written about previously, we emphasize that vertical integration is not always benign and indeed has the potential to create significant anticompetitive harms. In this post, I summarize and highlight some of the points made in our comments.

First off, it is important to understand that vertical mergers of, say, a wholesale distributor and a retail outlet, have the potential to harm competition and hurt consumers just like horizontal mergers—mergers between two rivals—do. Indeed, in some cases, a vertical merger may remove the most likely potential rival to an incumbent firm.

Consider, for example, the case of Live Nation Entertainment Inc.’s merger with Ticketmaster in 2010. In that case, Live Nation’s concert promotion and venue business prepared Live Nation to enter into the ticketing platform business, but the merger with Ticketmaster undermined that nascent competition. Indeed, Live Nation had already begun that entry before the merger. This is why a vertically related firm in one market (say, wholesale distribution) might be the natural entity to sponsor entry against a dominant firm in a related market (say, retail sales), and that potential sponsorship could be undermined on account of the merger between the dominant firm and the vertically related one. That is particularly true in evolving or fast-growing sectors such as technology markets.

Second, it is important to recognize how vertical mergers, once completed, can be used to undermine existing rivals or raise entry barriers that make future entry materially more difficult. Colorado, like other states, has addressed such dangers. In June 2019, Colorado took action to prevent anticompetitive harms from occurring as a result of the merger of DaVita Inc. and UnitedHealth Group Inc. In that case, UnitedHealth, a health insurer, was facing an upstart rival, Humana Inc., which undermined UnitedHealth’s once-dominant position in the market, leading it to drop from around 75 percent to around 50 percent of the Colorado Springs Medicare Advantage market. Humana’s growth in this market reflected, on its account, its strong relationship with DaVita’s physician clinics in the area.

The acquisition raised the threat of customer foreclosure by limiting access to the relevant patient population. UnitedHealth already had an exclusive arrangement with Centura Health, another clinical network. This acquisition would give UnitedHealth control over DaVita. As a result of this merger, UnitedHealth would have the incentive and ability to increase costs for DaVita’s services to UnitedHealth’s rival insurers, or even to withhold such services altogether, leading Medicare Advantage rates to go up and/or quality to decrease. To prevent this harm, our state office required that the DaVita contract be extended and that UnitedHealth end its exclusive contractual arrangement with Centura Health. By doing so, the remedy protected Humana’s access to doctors who can enable access to Medicare Advantage customers.

The DaVita/UnitedHealth case is one of many examples of how vertical mergers can be consummated for the purpose and effect of excluding rivals or raising their costs. In some cases, such as this one, the impact relates to access to customers. In other cases, the merger impacts access to critical inputs (termed by economists as “input foreclosure”). Consider, for example, the merger of Comcast Corp. with NBCUniversal, in which the Department of Justice in 2011 was rightly concerned that Comcast’s control of NBCU would lead Comcast to limit the ability of rival upstart online distribution platform companies to access NBC content, a critical input into their own offerings.

Similarly, the proposed 1998 merger between Ingram, a leading book distributor, and Barnes & Noble, then the dominant book retailer, threated to entrench Barnes & Noble’s dominant position. At the time of the merger, Ingram was Amazon.com Inc.’s leading supplier, filling more than 58 percent of its orders. With respect to the merger, Amazon.com and independent booksellers raised a series of concerns as to how the merger could harm competition in retail books sales, including on issues such as “credit, speed of delivery, and access to popular titles.” In the face of opposition by the Federal Trade Commission, the merger was abandoned.

In addition to highlighting the prospect of competitive harms on account of vertical mergers and discussing the types of evidence that could be collected to challenge such mergers, the comments submitted today to the two federal antitrust enforcement agencies by the state attorneys general also discussed the use of merger remedies. Many vertical mergers offer the opportunity to impose a conduct remedy that can allow the merger to go forward while blocking anticompetitive outcomes.

In the UnitedHealth/DaVita merger, for example, Colorado’s remedy did just that, extending an existing contract and banning an exclusive contracting arrangement that bolstered UnitedHealth’s market position. In other cases, however, such remedies may well be impractical or difficult to administer in practice. Where monitoring and administration of a decree may be difficult, the better course is to simply prevent the merger from taking place—as happened in the blocked merger of Barnes & Noble/Ingram—rather than attempting to implement a conduct remedy that is prone to abuse and may well prove ineffective.

As captured in our comments, State Attorneys General play an important role in protecting their citizens from anticompetitive consolidation. By sharing our experience, we are doing our part to help ensure that the federal merger guidelines are effective in protecting competition.

—Phil Weiser is Colorado Attorney General, sworn in as the State’s 39th Attorney General on January 8, 2019.