“Equitable Growth in Conversation” is a recurring series where we talk with economists and other social scientists to help us better understand whether and how economic inequality affects economic growth and stability. In this installment, Equitable Growth’s Executive Director and Chief Economist Heather Boushey talks to David Weil, currently the Peter and Deborah Wexler professor of management at Boston University’s Questrom School of Business. Weil will become the dean of the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University in the fall. They talk about Weil’s research on the “fissured workplace,” the influence of monopsony power, the rise of interfirm inequality, and his experience in government.

Heather Boushey: Thank you so much for taking the time to do this interview. Your research and writing on the fissured workplace has been so important for understanding what’s happening to the U.S. labor market over the past several decades. I want to run through your ideas, but I also want to tap into your experience as a policymaker. You just spent three years working for the Obama administration, putting your ideas into action, and I’d like to hear a little bit about that.

We can come back to that in the end, though.

I had the pleasure of co-editing “After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality,” which of course is a volume you contributed to. And your chapter was on the fissured workplace. I’d like to start off this conversation by asking you to explain what you mean by that. Not everyone who’s listening to this or reading this will have heard your argument. What does a fissured labor market look like?

David Weil: The whole idea of the fissured workplace grew out of thinking about a bunch of phenomena that had been happening to the labor market, with business organizations outsourcing, subcontracting, and third-party management. I had been studying in various projects the changes in business organizations and thinking about some of their impacts on compliance with workplace standards and other labor market outcomes. And at a certain point, it started to strike me that there were common elements about these different activities.

First of all, public and private capital markets were pushing businesses throughout the 1980s to talk about what’s their core competencies and to kind of focus increasingly on what were they delivering to their customers? And what were they delivering to investors in terms of the value they’re creating. Living in a business school has made this sort of something I hear a lot as well. And as you know in economics, there’s nothing inherently wrong with specialization. It has been a driver in so much of economic history and business development. But the pressure over the past decade seemed to be at an almost laser focus.

So you started to have companies really shedding anything that wasn’t core to their definition of value creation. And that led to the second element you see in fissuring, which is this desire to shed anything that doesn’t contribute to the perceived core competency. If you look at different businesses and industries, the process of shedding plays out somewhat differently, but the basic evolution is they start by shedding things like payroll, accounting, information technology, publications, things that they can find other players to provide, usually at a lower cost.

But then you start seeing that the activities they’re shedding continues. It’s like businesses started to say, “Hey, this is actually kind of cool. I can get this stuff done, and instead of paying, let’s say a wage, to a person to do something, I am paying a price to get the same activity.” And so that shedding starts moving inward to more and more activities that are pretty central to what that business does.

So, for example, in the hotel industry in the 1980s, the branded hotel industry got out of the business of actually owning properties. Instead, they came to define their core competency as managing portfolios of brands. And so you married a strategy of franchising the property to a strategy of simply owning the brand and making sure that the brand was being delivered by these properties. The property owners would pay you revenue for the use of the brand name or the brand affiliation through royalties, advertising, and licensing fees. The franchise owners get the benefits of the brand recognition but now face the problem of managing the property and hiring the workforce. We can talk about any number of industries where this process also started to happen. The pathways differ, but in each case, they’re shedding activities as almost a complement to pursuit of the chosen core competency.

But the third piece, which is really important in my mind to understand both the fissuring phenomenon and its public policy implications, is that companies needed some kind of glue to hold the first two elements together—like the hotel brand’s standards in the above example. Why? Because if I’m trying to maximize the value of my core competency but I’m shedding activities to other players, those businesses can undermine my core competency. So the third piece is creating some kind of organizational glue to make sure those other entities don’t stray, that they keep to task, that their incentives are aligned with the main company’s in a way that you still have the product delivered to quality or technical or time specifications, or all of the above.

This is why I think franchising started to spread to lots of sectors. It’s a form of business organization that allows you to shed and yet control. That’s the nature of a franchise agreement.

I think information technology facilitated this because you have lower-cost mechanisms to monitor subsidiary organizations or the networks of organizations that make up a fissured workplace. I think Uber is an example of exactly this, in probably the most technologically advanced form out there. But years ago I had studied the evolution of the supply chain in the retail industry, and the standards that came with those business arrangements are also about the glue. So you can find this glue manifesting itself in different places. That’s the key third element.

The idea of fissuring is really the combination of those three things applied in different settings that has the net effect of breaking apart the employee-employer relationship. Take the hotel example. Once the property was franchised, the owners of the property had limited knowledge about running a hotel. So you’ve got third-party managers running the hotel owned by a different entity under the specifications of the brand. And those third-party managers typically started hiring staffing agencies. They didn’t want to be the employers either. And so you have this deepening of the fissures. Subcontracting begets subcontracting.

Fissures like this also spread. They spread to other industries. They spread to other parts of the occupational distribution of a given industry. And the end result is you have broken apart the employment relationships. Sometimes this reflects employers trying to avoid their own liability under workplace laws and regulations. And that’s an important part of it.

But I think another part of the phenomenon that I’ve always been trying to emphasize is that it goes beyond avoidance of liability. Because if you think this is just about employers trying to weasel out of their responsibilities, you miss this more fundamental change, in my mind, that’s happening in business organization. And if you’re trying to ultimately deal with the consequences of that, then you’re underestimating the difficulty of unwinding that behavior or changing that behavior in some way to deal with the consequences in the labor market.

Boushey: So part of what firms got rid of are the management problems with all the subcontracting because managing humans is difficult, and nobody wants that piece, and so they want to separate that from all of the actually profitable parts of the enterprise. But they’re paying a price rather than a wage, right, which of course is what Uber does. Yet there are all these rules, which means the company is still in control. Traditionally, we’d have this distinction between a contract and being an employee. But it seems like you’re suggesting that there’s something more to the management problem than just the responsibility.

Weil: No, I think you’re exactly right about both elements. Managing people is messy. And businesses, if they can push that to someone else who can do that problem for them more effectively, they’re going to do it.

There’s a really interesting guy in capital markets. You’ve probably met this guy, in the financial services industry, Steven Berkenfeld, who’s at Barclays Bank. Steve has been thinking a lot about the future of work, and I’ve appeared in some of these future-work seminars with him. He likes to quote Henry Ford, who asked why he had to get the rest of the worker when all he wanted was his hands. Steve has talked about this insight in the financial services industry after the financial collapse, when there was a scrambling to cut costs as much as possible. Some of that was accomplished by companies shifting work out of financial services industries to contractors.

This vignette from that industry, which I think is suggestive of what you’re talking about, is once they did it, they suddenly said, “Oh my gosh, so much better. We don’t have to deal with messy humans. We can just pay for this other company to deal with it. And we don’t have to look into that box anymore.”

But I think this is a public policy fallacy because they are still setting so many of the terms about what that box does. In terms of how we think about this in terms of public policies, what I sometimes call the lead company is still dictating outcomes, performance goals, and very specific things that they want those entities to do. In so many ways, their hands are still all over matters that are still about the employment relationship. But they have created this market distinction between their activities and those of the subsidiary.

I think the management piece is a big part of it, but again, with the caveat that they have created a glue to make sure they follow what is required to achieve core outcomes for the lead business.

But another critical impact of fissuring that you noted is its impact on the setting of wages. This is what I wrote about in my chapter for “After Piketty” that you edited. The wage-setting process is transformed by shifting out work. Why is it that companies set single wages for a job? Why do they set standard wages rather than be a price discriminator and set a wage so that each worker gets only their marginal product of labor? It’s because people are working within the four walls of the same entity. We are social animals, and equity norms come up. And people compare their wages, whether they are allowed to or not.

Boushey: Yes, they do.

Weil: People know. People know. They are very aware. And because people are aware, employers are aware. And so you have more uniform wage policies. You have standard wages.

There was a big literature in the 1990s about why did large firms pay more to certain workers than otherwise equal workers in smaller firms? And the answer, to me the most compelling answer, is things like fairness and equity. That if you’re in the structure, if you are a janitor working at a GM facility, you know what the people on the assembly line are earning. And that tends to pull up your pay.

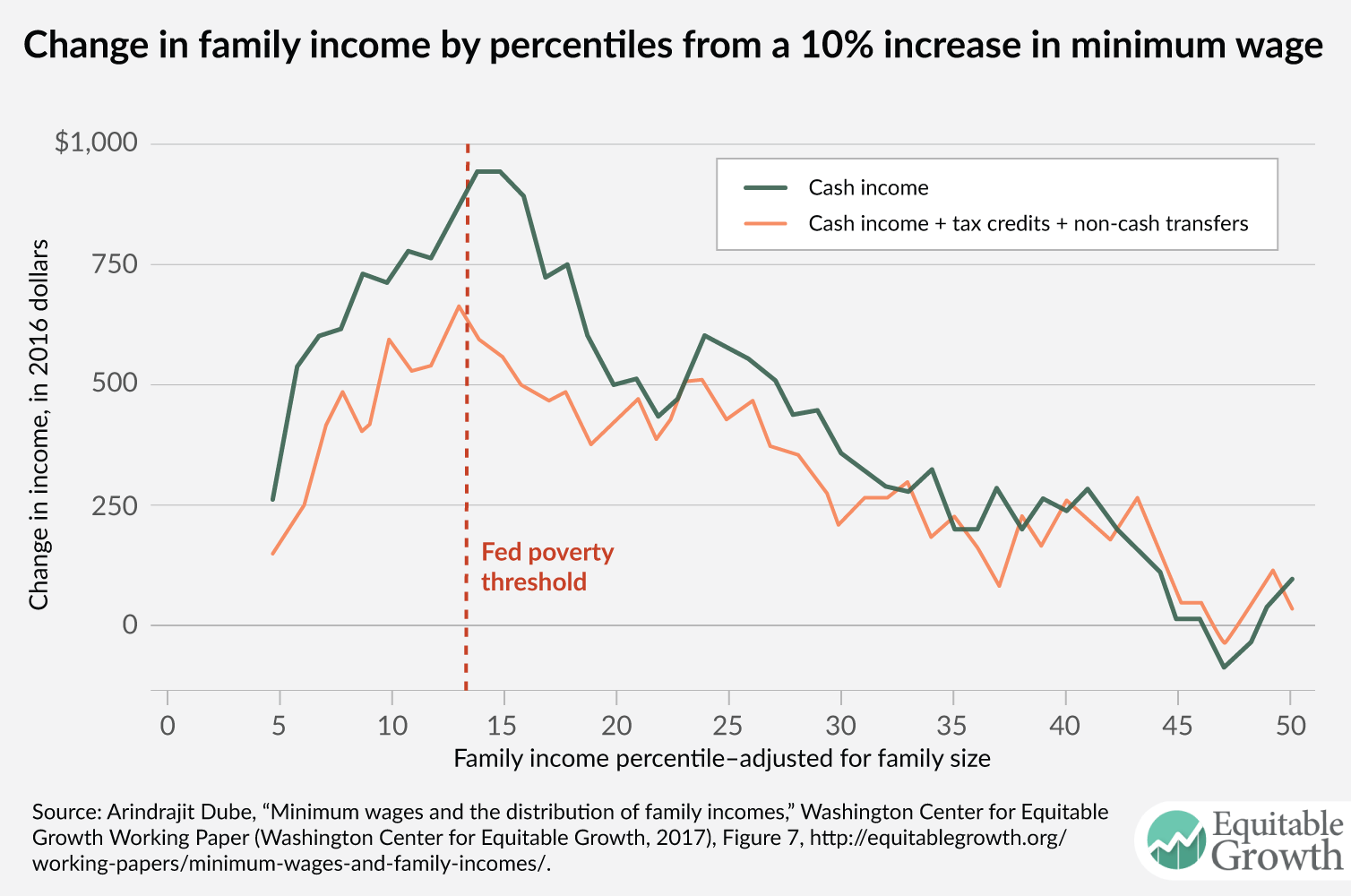

And we know from the work of [University of Massachusetts-Amherst economist] Arindrajit Dube and [Boston University economist] Johannes Schmieder that there is a premium for being in-house versus broken away from the mothership. Once work is being paid for by a price as opposed to a wage, then it’s no longer a wage-setting problem, and so a lot of those equity norms change.

From an employer’s point of view, they can breathe a sigh of relief. They don’t have to deal with that anymore. They don’t have to deal with the fact that it’s complicated to think about “What should I be paying the folks who are doing the landscaping because they’re no longer my employees? They’re just this thing I outsource.”

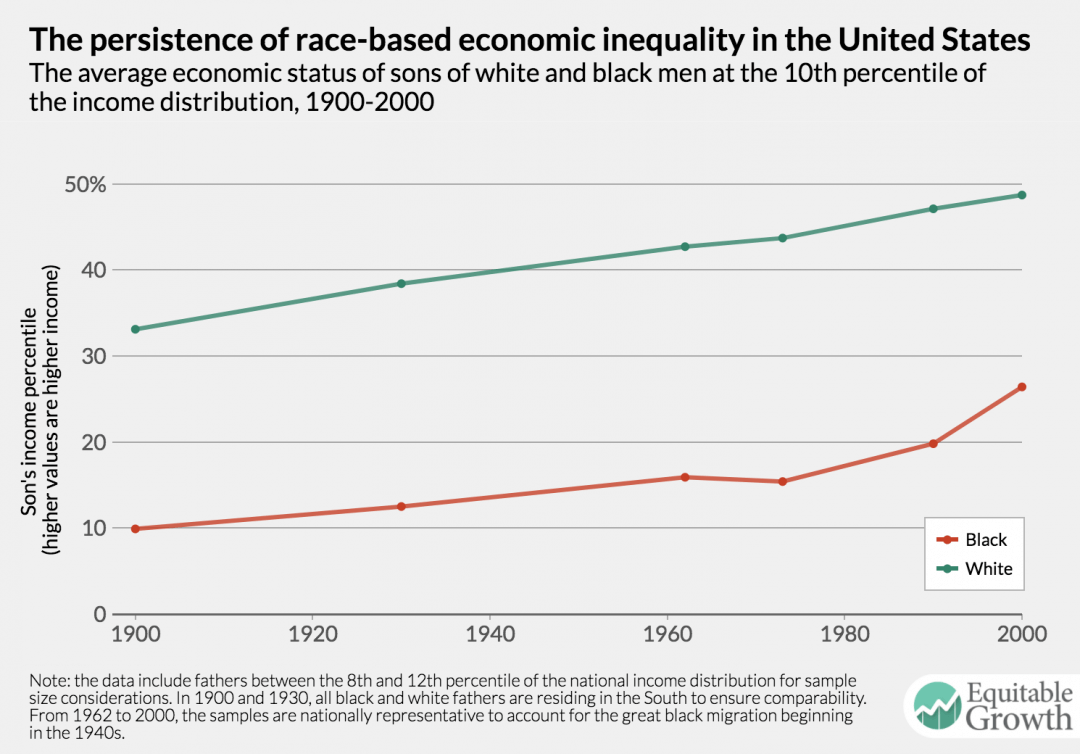

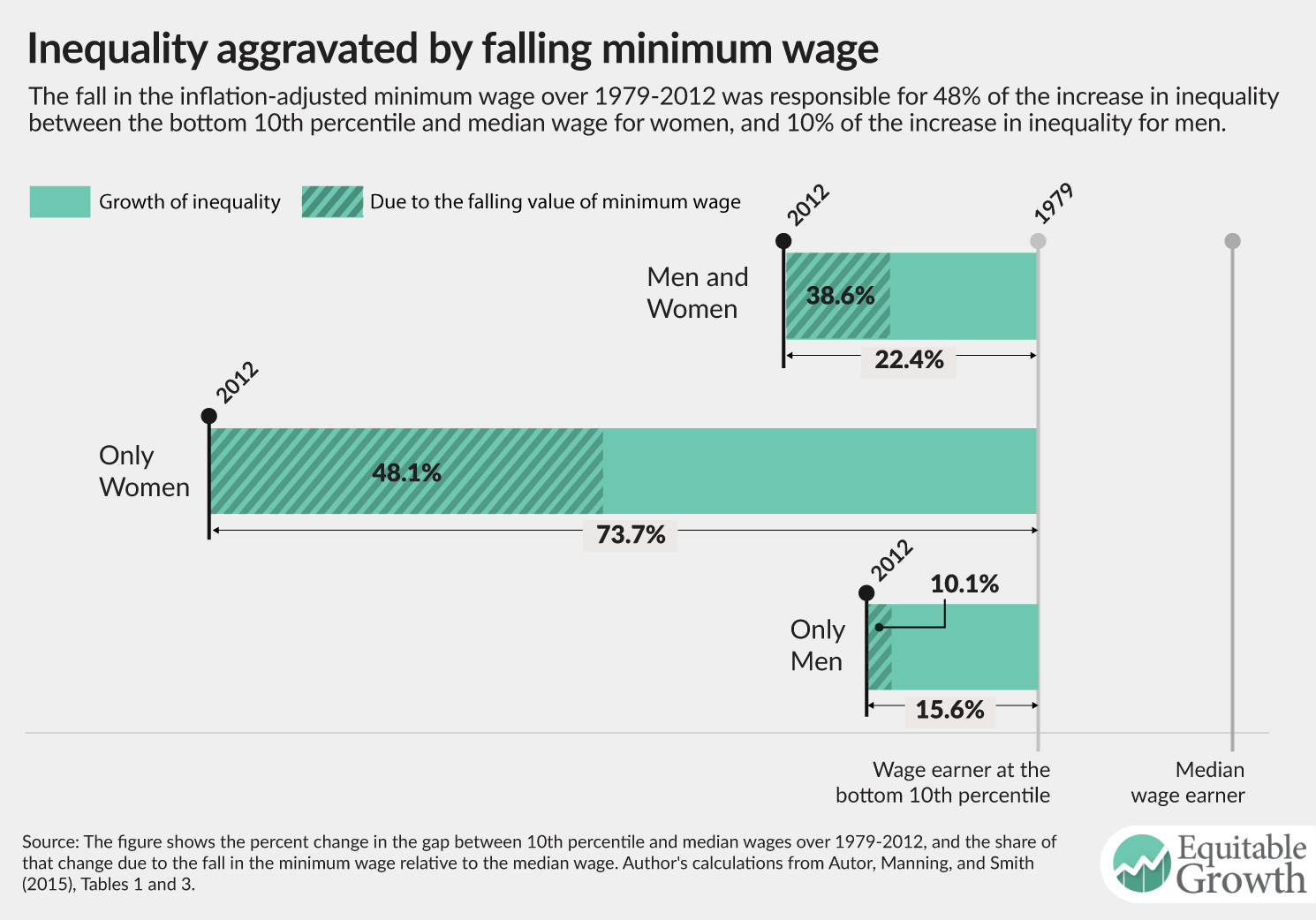

I think that has consequences. What’s driving inequality, to me, comes back to the fissured workplace. It comes from the consequence of shifting the wage-setting problem to all these other entities and kind of getting out of that fairness bind that employers otherwise have to deal with differently.

Boushey: Exactly. Saying that a janitor is going to be paid a higher wage in a larger firm means that labor markets aren’t perfectly competitive, right? So one of the questions we’ve become a little obsessed with at Equitable Growth is market structure and competition and monopoly and monopsonies. Talk to us for a little bit about the role of monopsony in the fissuring of the workplace.

Weil: Part of the way I view fissuring is as a way to deal with the problem of setting monopsony wages. It’s hard to do that if they’re your employees. It’s much easier to do if I am setting prices for a bunch of janitorial firms in different facilities. Then I have a bunch of prices and I put it out to competition. And if the janitor in Facility A is being paid differently than the janitor in Facility B, that’s not my problem. I’ve just hired two different firms. And once you break out of the problem of having a single price, what do you do? You do price discrimination.

In my mind, by fissuring, you are able to do essentially wage discrimination without having to set wages. You’re doing it through the pricing mechanism. I think this has had a big effect, in particular, on lower-wage work. You are pushing that kind of work to a set of firms who are in higher levels of competition with each other. Studying the labor market from my perspective would certainly lead me to believe that labor markets are far from perfect, but I think companies are pushing wages closer and closer to what we would think of as marginal productivity. And some of the rents that used to be collected by workers because they were inside a firm, even a nonunion firm and certainly in a unionized setting, are now going back to the companies because the companies are playing close to what they actually need to pay to entice people to do that work.

At the same time, you have these firms that are shedding activities but also are rapidly moving up. So if you are lucky enough to be in the Google mothership, you soar up with that wage structure. You’re moving up because your company is moving up. And wherever you are, whether you’re an engineer or an executive, the whole pay structure’s moving up. And then you have these businesses in the shedded parts of the economy where those pay structures are being pushed downward, closer to the marginal productivity of labor. And even the executives in those businesses who are providing these services for the lead companies in the economy are not doing nearly as well because they’ve been separated from the same kind of mothership relationship. I think we really need to better understand how a wage is determined in those enterprises.

Boushey: So this leads to the issue around who captures the rents. There’s a body of research showing that the distribution between the amount of national income going to labor versus going to capital has been changing over time. Increasingly, it seems like one of the big research questions out there is “What is the connection between the two?” Where do you think some of the research questions are that you think are most pressing for us to start investigating?

Weil: There’s this paper right now that [Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist David] Autor and [Harvard University economist Lawrence] Katz and [MIT economist John] Van Reenan have about the diminishing labor share tied to essentially increased concentration of firms, or those industries with higher concentration ratios on the product market side are also ones where you see diminished share of income going to labor. I think that is a phenomenon very consistent with what I’m talking about, about the separation and the rushing apart of businesses from those that are still able to capture the value and capture the rents. And at the end of the day, they might have a lower labor share because of the part of the work they’re doing.

If you are a major hotel chain right now, a hotel brand, a big part of what you do has to do with creating and sustaining brands. It’s not employing people who are cleaning rooms anymore. That’s going to other entities. This is the mechanism that actually allows or enables that separation to exist. And what I think we don’t know enough about is whether the wage-setting policies in both the entities are moving down in the distribution of businesses and the entities that are quickly moving up the distribution.

You know, I think in one sense the entities that—and here I’m thinking about this interesting experimental literature that I associate with people like Ernst Fehr, who has studied equity norms and fairness norms inside businesses, inside firms. I think a lot of that probably still holds. That you still are very cognizant of pay differentials.

You were joking before about everyone in firms knowing what other people are being paid, and therefore employers want to keep everyone happy because they don’t want to lose people. But I think we need to know more about the moment when employers say, “You know what, wouldn’t it be nicer if we shifted them out?”

I don’t think the shifting out has stopped. I am fascinated and concerned by the increasing number of higher-education jobs that are being shifted out. And I think that again becomes the operative question. It isn’t so much “How do I set salaries of all of those in the mothership?” It’s “Who am I deciding to jettison next?” And if you look at the structure of law firms, they’ve been transformed too. More and more of the mundane, day-to-day legal work has been shifted out to contract kinds of operations in the legal field. And you’ve had this separation of earnings. If you are a lawyer but no longer in one of these decreasingly common big law firms, then your returns as a lawyer have gone down substantially.

I’ve always found it very interesting when I talk about some of these things with journalists. They quickly say, “Oh yes, you’ve just described my life.” You know, “I would have been a full-time reporter.”

Boushey: Now they’re doing freelance.

Weil: Yes. Everyone’s freelance. A lot of the underlying logic of the fissured workplace I think has now spread to lead companies and caused them to think more and more about “Who else can I shed?” That, to me, is part of what the research agenda needs to continue to look at. What are noncompete agreements about? Why are noncompete agreements becoming so common? There’s the absurd noncompete agreement that Jimmy John’s hourly employees had to sign. It would not surprise me a bit that we’re going to see more and more of that work of people with higher educations also being affected by these trends.

Boushey: Are there any other research questions that you think are really pressing? And I ask in part because Equitable Growth is a grantmaking entity. We are looking for scholarship to support, and we’re trying to entice people to ask research questions that are really important to policymakers. Your advice would be super helpful.

Weil: I think we don’t understand enough about wage norms. I’m primarily now thinking about those labor markets where people are more subjected to the brutal pressure of the market. We still don’t know enough about where referent wages are and how you can affect those, and what people look to, and how that might vary. How important are social networks to the propagation of wage norms? How do they work out? How geographically focused are they? How do they play out in labor markets where ethnicity is important?

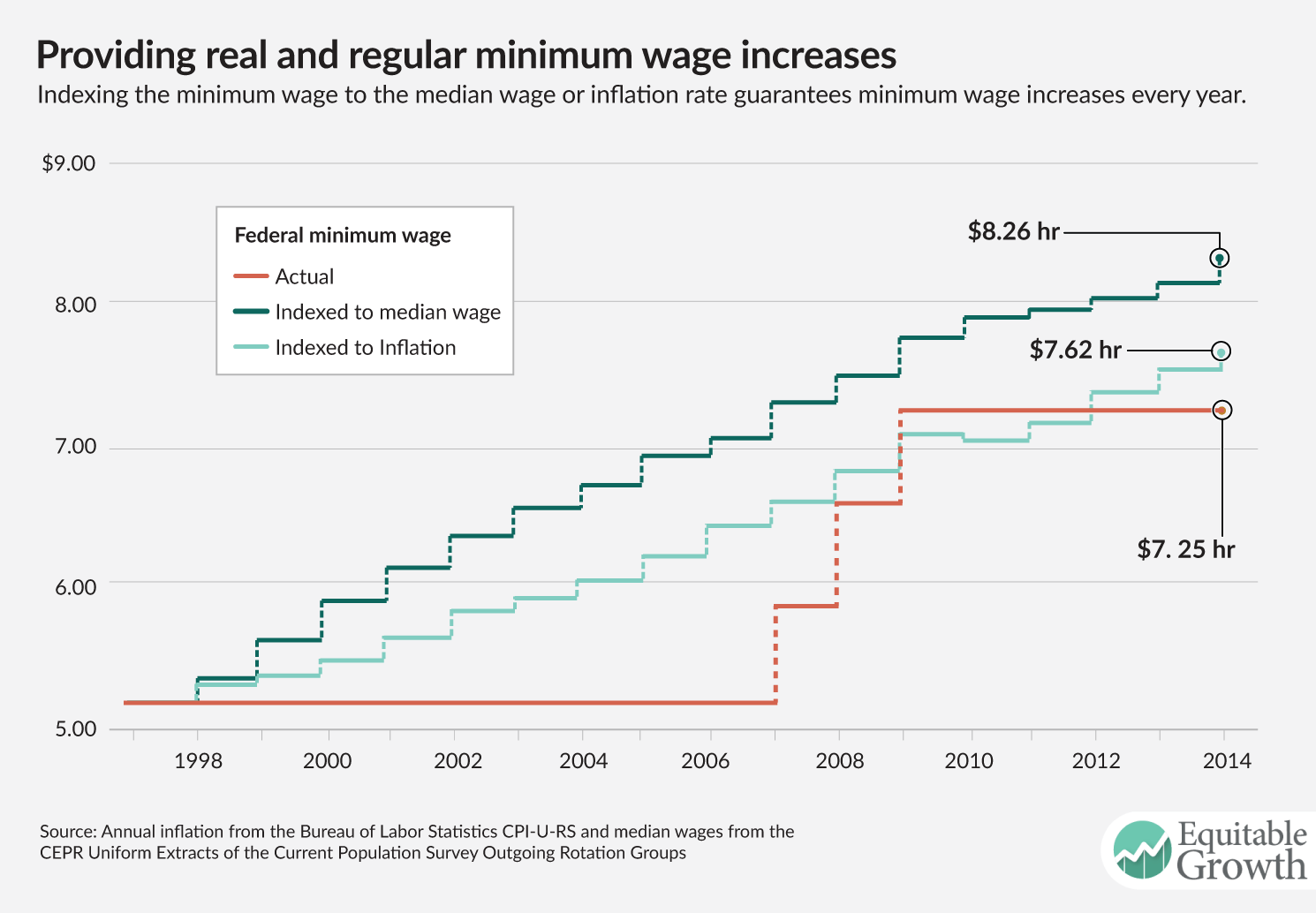

I think all this is important for its own sake in understanding the dynamics of this increasingly fissured workplace. But I also think from a public policy point of view, our policies don’t pay enough attention to how wage norms are set and then as a matter of policy to how to move those upward. I would offer as an anecdote the “Fight for $15,” which I would cast as a really successful social movement. By trying to affect the wage norm, that $15 becomes salient. I think it’d be fascinating to know where you have labor markets that feed, let’s say the fast food industry, where you’ve seen that change in the reservation wage because of the impact of that social movement.

Boushey: In an era where so few workers are unionized, to what extent does that become the marker of a good firm? A personal anecdote before you answer the question. I’m working with someone, and we’re looking for a venue for an event. But it’s in a place where there are no unionized hotels. And so one question we have is “Could we use $15 as the demarcation that takes into account some sort of labor standards?”

Weil: Right. Right. Right. Yes, and I think that’s a great example. I think I’ve always been somewhat of a skeptic of corporate codes of conduct and things like that. I think I’ve been more skeptical because I find often that people who are promoting those codes don’t seem to have an understanding of some of the issues of wage norms and how what they’re trying to do might fit into that. That being said, I think if we did have a better understanding, you could see how the decisions of private players and other innovative forms might be able to ultimately affect things that we care about in a public policy consequence.

Right now, in a world where we don’t know what the federal government’s going to be doing in terms of protecting basic labor standards, it seems to me that’s even more important because you need to then act on those wage norms, to try to do what we would normally do through minimum wage or basic labor standards policies.

Boushey: Well, so let’s use that as a segue to you just coming out of surveying for three years in [the U.S. Labor Department’s] Wage and Hour [Division], making decisions around policy. Is there an example of something where your research influenced what you and other policymakers did?

Is there a good example of something where you were studying something and then made something happen or tried to make it happen?

Weil: I came into Wage and Hour having had the wonderful opportunity of advising it for a number of years. I was lucky enough to think about some of these issues before coming into it. I think one of the hardest things walking into an agency like that is if you don’t have an agenda, the day-to-day problems that come across the desk can completely swamp you. And if you don’t have a vision about what you’re trying to do as an agency, or as a leader in an agency, it’s very difficult to chart a course.

I came in very much with having had an opportunity already to think about and, in some sense, engage with the department on what kind of changes you needed to make to deal with the fissured workplace. I really thought about my job in terms of two huge external pressures.

One was the fissured workplace and the complexities it creates for a labor standards agency. Who’s the employer and who should we be worried about compliance is a very complicated thing to deal with. That problem overlays on a long-standing problem, which is a resources allocation problem. The Wage and Hour Division oversees laws that cover 135 million workers in 7.3 million workplaces. President Barack Obama had increased the size of our investigation force from its all-time low to 1,000 investigators. So we had 1,000 investigators to oversee 7.3 million workplaces. And those workplaces were increasingly fissured.

My obsession was how do we move more and more of our resources to a proactive approach on enforcement where you’re explicitly trying really to change behavior. Not just to recover back wages for workers. That’s obviously really important. But in my view, given those two forces, what you really have to be thinking about is changing the behavior of organizations so they comply in the future. And using every tool you have available to you, which starts with enforcement.

We had not historically used all of our enforcement tools. We had tools in the tool chest we had neglected to use. So we started to aggressively recover liquidated damages along with back wages. We started to use civil monetary penalties much more aggressively. We started to dust off what the law gave us and use those tools more effectively. We changed the relationship with our solicitor’s office so that our investigators were often thinking about “What or how can this translate into something that will really have greater effect through a litigation-based strategy?” Those are all tools of trying to use your enforcement tools to greater effect.

Secondly, we shifted away from being an agency where 75 percent of our investigations came out of complaints, which is typical for most enforcement agencies. Our view was that if you do that, you’re inherently reactive. And even more so, we wanted to focus on low-wage, vulnerable workers, who are obviously the ones most affected by violations. If you just follow complaints, you’re kind of thinking that the people who complain are those people, and they’re not. And so we had a lot of statistical analysis done.

And this was one of the projects I’d worked on years before, to show that industries with the highest levels of problems, objectively measured, were some of the ones with the lowest complaint rates. So you have to move an agency away from a complaint-driven culture toward one that’s using more of its resources for proactive, essentially agency-initiated investigations.

And by the time I left, almost 50 percent of our investigations were directed proactive ones. And the 50 percent that remained, complaints, we had changed the mechanism used for triaging. We were triaging incoming complaints so that it was no longer first in, first out but rather evaluating the incoming complaint and asking questions like “Does this complaint suggest a bigger problem? Is this a complaint that maps onto our larger proactive initiatives?”

And then another major element we focused on, and this goes to the fissured workplace, is where the back wages are owed because those workers are usually living on the bottom of some fissured structure, such as at the subcontractor level. And if you think about it, that subcontractor’s CEO, so-called CEO, is probably a small-time operator who’s got a very thin margin because the price they’re being paid is being set by someone up the chain, and so on. We really took a lot of heat from saying, “Well, the statute says there’s joint employer responsibility.” But we had a major initiative on joint employment so that we could make sure that pressure was applied to all relevant parties that contributed to the violation.

We put a lot of energy into misclassification of workers because, again, I think that misclassifying someone as an independent contractor rather than an employee is often something that happens at the bottom of a fissured structure. We wanted to say, “Look, you can’t just call people independent contractors because you don’t want to have to bother with all of the things associated with an employment relationship.”

Whether through the mechanism of joint employment, or simply the mechanism of saying “Look, you might not be the employer of record but if you are sitting as a key player in this whole structure, then you are setting standards. You are hiring staffing agencies. And therefore, we want you at the table.” And we did a lot of different initiatives to pursue this broader approach to enforcement and outreach.

One of the best examples, I think, is in the summer of 2016, when I signed an agreement with president and CEO Suzanne Greco of Subway sandwiches to create a voluntary compliance arrangement across that company’s franchise system. Subway understood and acknowledged their interest in improving compliance among their 13,000 franchised outlets and the tens of thousands of employees who worked for them. The company had a history of years and years of problems and violations. The agreement was built on my agency’s and the company’s mutual interest in addressing those problems in a more systemic fashion. That was the kind of agreement I was happy to sign partly because I wanted to see if that kind of thing could also work and partly because it was another way of bringing in a higher level of a fissured structure to the table and figuring out “How can you move compliance in that way?”

All of those ways and many other efforts were the long game we were trying to play. And I think we really did move the needle in a lot of those areas.

Boushey: Well, it also just shows the importance of government spending if you’re asking resource questions that are important in the real world, and thinking about how we’re going to apply them so that when you have that opportunity, you’re really able to take that depth of knowledge and make it into something real. It’s very impressive.

Thank you so much for the interview. But mostly, thank you for your service and all the work you’ve done to make workplaces better for millions of Americans.

Weil: Thank you.