I recently wrote a critique of the Tax Foundation’s macroeconomic model in the context of the organization’s score of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act as introduced by House Committee on Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady. In that critique, I identified two flaws in the Tax Foundation model. First, the interaction between federal and state corporate income taxes in the model was—at the time the critique was published—incorrect. Second, the organization’s approach to modeling the estate tax is incorrect and, moreover, inconsistent with other assumptions made in its modeling.

The Tax Foundation subsequently acknowledged the first error. However, the organization also published a response in which the authors assert that the organization’s approach to modeling the estate tax is reasonable. In this note, I evaluate the Tax Foundation’s response to my critique and conclude that it does not justify the organization’s current modeling approach. There appear to be important flaws in the Tax Foundation’s treatment of the estate tax that affect every dynamic score the organization has produced for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

As noted in the original piece, I am unable to offer a complete assessment of the Tax Foundation model, which would require information about the equations that make up the model that is not publicly available. I continue to have substantial concerns about the Tax Foundation model beyond those described in the original piece or this update. These concerns are not merely about the appropriateness of the individual assumptions the Tax Foundation relies on in its modeling, but also about whether the seemingly ad hoc collection of equations that make up the Tax Foundation model form a coherent whole. The Tax Foundation’s response to my concerns about its modeling of the estate tax highlights the importance of this second concern.

The Tax Foundation’s assertion that the marginal investor is subject to U.S. taxes on savings likely cannot be reconciled with its small open economy assumption

The most striking element of the Tax Foundation’s response regarding the estate tax is its assertion that the marginal investor in the U.S. capital stock is a domestic investor and thus subject to U.S. taxes on saving. That assumption is consistent with a closed economy, or one in which there are no international capital flows or trade. In a closed economy, domestic investment is necessarily financed entirely by domestic savings.

Yet the Tax Foundation has repeatedly endorsed the idea that the United States is appropriately modeled as a small open economy. In a small open economy model, there is no necessary relationship between domestic investment and domestic savings, as any required funds can be obtained from investors abroad. The classic small open economy model is thus one in which the marginal investor is foreign. As a result, the rate of return on investment (after accounting for taxes imposed at the business level) is determined by global capital markets and is unrelated to the particular circumstances of the domestic economy. There is an obvious tension between the assumption that the marginal investor is domestic and the assumption that the United States is a small open economy.

The Tax Foundation justifies this inconsistency on the grounds that the marginal business investment is higher risk and foreign investors are relatively more risk averse. Thus, even though foreign investors could invest in U.S. business assets, they choose not to do so. The Tax Foundation further asserts that in response to a reduction in the tax rate on capital income foreign investors increase their holdings of low-risk U.S. assets, such as government debt, and domestic investors shift into higher risk assets, such as corporate stock. As a result, the Tax Foundation explains, “the United States can have strong financial inflows while the marginal investor remains a domestic investor.”

Notably, this justification for the assumption that the marginal investor is domestic even as the rate of return is fixed—because the United States is appropriately modeled as a small open economy—appears to exist entirely outside its model. As best I can determine from the information publicly available, the Tax Foundation model itself appears to include no explicit model of markets in government debt (or other low-risk assets), the composition of savers’ portfolios, and the allocation of assets between domestic and foreign investors. Thus, while the Tax Foundation asserts that a difference in risk tolerance between domestic and foreign investors justifies its modeling assumptions, it is simply impossible to consider these issues rigorously in the organization’s macroeconomic model.

Notwithstanding the impossibility of a direct assessment of these issues in the Tax Foundation’s model, a model that seriously grapples with these issues would likely work quite differently from what the Tax Foundation suggests, for at least two key reasons:

- If the marginal investor is domestic then the supply of capital is likely to be far less elastic that the Tax Foundation assumes. If domestic savers are the sole source of funds for business investment at the margin, then reference to the global supply of savings is not sufficient to justify a fixed after-tax return on that investment—the cornerstone of the Tax Foundation’s modeling approach. Instead, the relevant question is whether domestic investors are willing to provide the necessary capital and at what return. Moreover, if business investment is riskier than other types of investment, then it suggests that domestic investors would require a higher return to compensate them for taking on that risk as they increase their investment in these relatively higher-risk assets. (A precise evaluation of the latter issue would require a model of the supply of savings in which the potential impact of changes in wealth on risk aversion and other issues could be weighed against the effect of an increased exposure to higher-risk assets.)

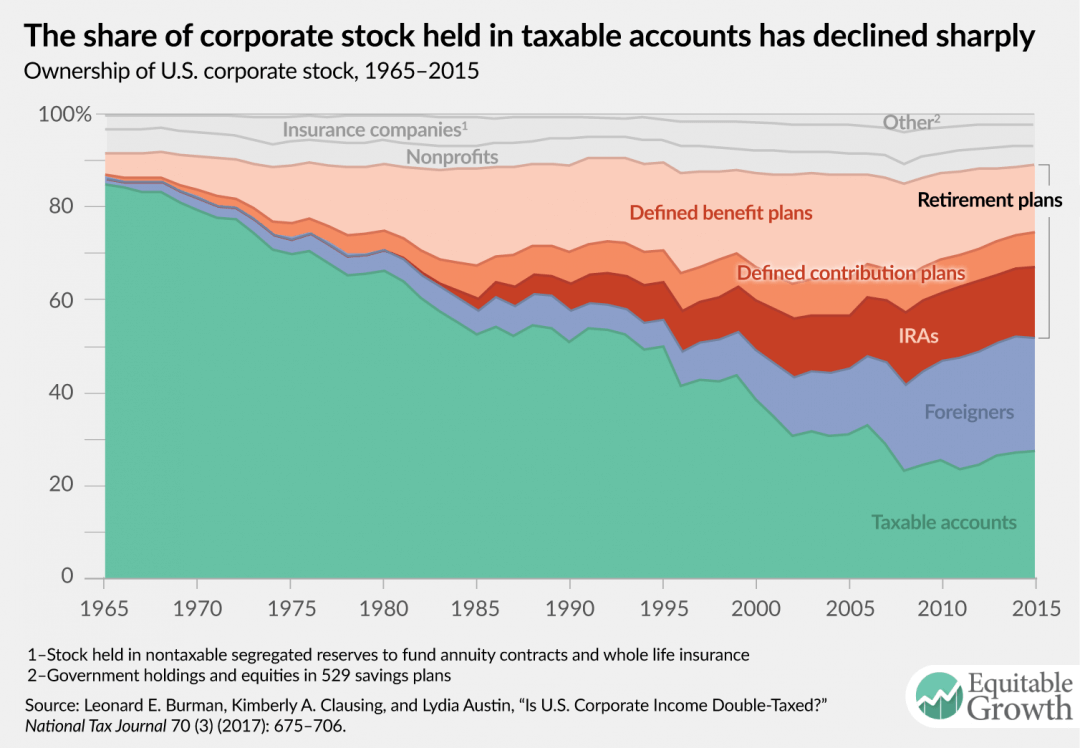

- The claim that foreign investors are never marginal for business investment decisions is empirically untenable. The assumption that foreign investors are unwilling to invest in relatively higher-risk assets regardless of the differential between the U.S. return on investment and the foreign return is difficult to justify. In the Tax Foundation’s model, this differential appears to be large and determined solely by the parameters of the U.S. tax code. Yet recent empirical analysis suggests not only that foreigners own U.S. corporate equity, but also that the share of corporate equity owned by foreigners has grown markedly in recent years. In addition, the U.S. corporate sector includes foreign-parented firms. The implicit assumption that foreign-parented firms are unable to access capital abroad is likewise difficult to justify.

In short, the Tax Foundation assumes a fixed after-tax return consistent with a small open economy model, assumes an effective marginal tax rate consistent with a closed economy model, and explains the inconsistency between these two assumptions by reference to an argument about risk and ownership that appears to exist only outside its model and that suffers from at least two major weaknesses.

The Tax Foundation’s response thus raises the question of whether a rigorous justification for the apparently ad hoc collection of equations that make up the model has been—or even can be—constructed.1

The Tax Foundation’s response does not justify its assumption that the estate tax affects the marginal investor

The Tax Foundation model features homogeneous capital. In other words, there is nothing unique about assets held by one business relative to those held by others or about the capital provided by one investor relative to another. If capital is homogeneous, then there is no reason the marginal supplier of capital is necessarily subject to the estate tax. This is particularly true if the marginal investor is foreign, as would be the case in a small open economy model. But it can also be the case if the marginal investor is domestic, as in a closed economy model or as the Tax Foundation suggests.

Suppose all individuals discount future consumption at the same rate (an assumption broadly consistent with the style of modeling the Tax Foundation adopts), the supply of savings is infinitely elastic (as the Tax Foundation would likely need to assume to justify its other results), and only a small minority of the population with wealth far above average is affected by the estate tax (as is the case in practice). Then the estate tax would likely not be marginal to the supply of capital even in a closed economy model. In such a model, the estate tax would cause some households to reduce their savings, but other households would be willing to increase their savings to exactly offset this reduction, leaving the overall supply of savings and the return to the marginal investment unchanged on net. The marginal investment, therefore, would be financed by an investor who is not subject to the estate tax.

The Tax Foundation’s response on this point ignores the fundamental issue. The Tax Foundation explains how the estate tax can affect financial incentives for a hypothetical household and, therefore, may affect that household’s savings decisions. Yet the issue I raised—and the one that matters for the effect of the estate tax on the economy—is whether and how changes in behavior by households translate into a change in the equilibrium rate of return, the return that generally prevails in financial markets. As the example above illustrates, the mere fact that the estate tax affects the incentives of a given household does not necessarily imply that the estate tax has any effect on the equilibrium return.

Thus, when the Tax Foundation incorporates an average estate tax rate into its cost-of-capital formula, it is making implicit assumptions about the distribution of the increase in domestic savings that would finance an increase in the capital stock and whether those assets are held at death (probabilistically). These are the assumptions in question. The Tax Foundation’s response does not discuss these assumptions and is thus inadequate to address the issue I raised.

The weakness of the response may reflect that (as noted above) the Tax Foundation appears not to explicitly model the sources of savings in any way. If this is the case, then the Tax Foundation cannot justify its assertions about the source of savings as they relate to the relevance of the estate tax in its model because the model does not address these issues.

The Tax Foundation’s justification for treating the estate tax as a nondeductible property tax paid by businesses is incorrect

Finally, there is the issue of treating the estate tax as a nondeductible property tax paid by businesses. As I discussed in my original critique, this treatment can generate spurious interactions between the statutory corporate tax rate and the estate tax rate that could cause the Tax Foundation to overstate the growth that would result from a reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate.

In response, the Tax Foundation argues that because the estate tax is akin to a property tax and because the estate tax is not deductible against income taxes, it is appropriate to model it as a property tax paid by businesses that is not deductible against the corporate income tax. This argument is incorrect because it ignores the distinction between a property tax paid by individuals and a property tax paid by businesses.

If, as the Tax Foundation asserts, it is appropriate to model the estate tax as a property tax paid by individuals, then the estate tax would increase the equilibrium rate of return required by investors in financial markets. The estate tax would thus have a negative impact on the capital stock, but would not interact with the statutory corporate tax rate in the manner that it currently does in the Tax Foundation model. A modeling approach that treats the estate tax as a property tax paid by individuals would not generate the spurious interaction I identified in my critique because decisionmakers within a firm would not analyze potential investments under the assumption that the firm itself pays the estate tax.2

The Tax Foundation itself acknowledges this issue elsewhere in its response to my critique. The Tax Foundation states that as “estate taxes are not paid by the firm, they only affect the discount rate of the individual.” In contrast, in their modeling, the Tax Foundation treats the estate tax as having no effect on individual discount rates and a direct effect on the investment decisions made by firms that behave as if they pay the estate tax. These two approaches are not equivalent.

Conclusion

A complete assessment of the Tax Foundation model is not possible given the limited information about the model available. Nevertheless, my original critique identified two flaws in the model. The Tax Foundation has acknowledged the first while arguing that the second is not actually a flaw. This analysis evaluates the Tax Foundation’s response to my critique and finds it lacking.

Moreover, the Tax Foundation’s response raises further questions about the organization’s macroeconomic model, including whether a rigorous justification for the seemingly ad hoc collection of equations that make up the model has been—or even can be—constructed. As noted in my original piece, these issues with the Tax Foundation’s model raise questions about the reliability of the organization’s estimates of economic growth and suggest that policymakers and the press should be skeptical of the results.