The federal minimum wage today stands at $7.25 an hour, unchanged since 2009 despite rising prices and rising nominal wages for other workers. Without legislative action by Congress every year—a very difficult policy endeavor—the minimum wage for the nation will continue to stagnate. New legislation now before Congress seeks to overcome that perennial policy hurdle by proposing to index the minimum wage to the median wage—the exact middle point in the overall distribution of wages in the U.S. economy—after first raising it to $12 an hour in 2020.

Indexing the minimum wage to the median wage would automatically increase the minimum wage so that it keeps pace with the typical worker’s wage. Currently, 15 states and the District of Columbia index or have future plans to index the minimum wage to the annual rate of inflation, so that when prices rise each year the minimum wage rises accordingly. Indexing the minimum wage instead to the median is different because it links the minimum wage to overall conditions in the labor market rather than to the general level of prices. In this way, those earning the minimum wage experience annual wage gains according to overall demand for labor in the market rather than a less-direct measure of prices. Moreover, wage indexing improves the ability of the minimum wage to reduce inequality.

Indexing the minimum wage to the median is preferable to indexing it to the average wage. Raising the minimum wage would affect average wages, whereas pegging the minimum wage to the median wage would not. This issue brief explains all of these economic reasons for indexing the minimum wage to the median or typical worker’s wage, and shows what an indexed minimum wage would like over time.

View full PDF here alongside all endnotes

Indexing the minimum to median wage is good economics

Indexing the minimum wage to prevailing wage levels accomplishes two goals. First, indexing to wage levels increases the efficacy of the minimum wage as a policy tool to reduce wage inequality. In particular, wage indexing ensures those earning the minimum wage will not increasingly fall behind the typical worker.

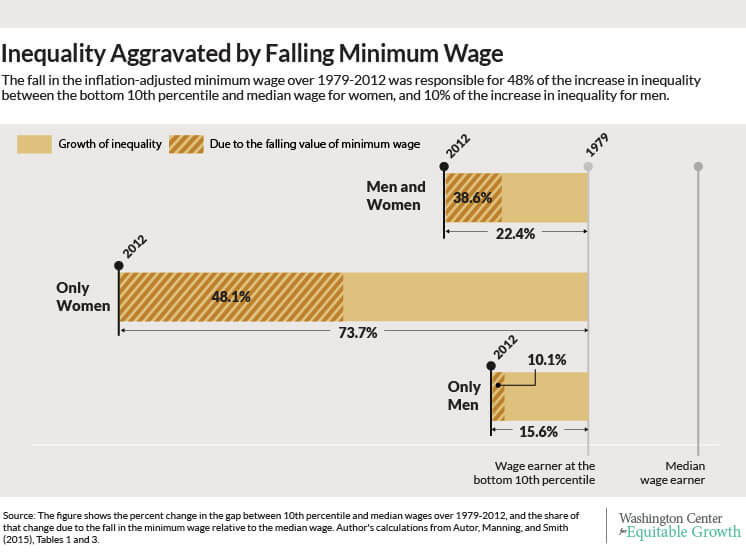

Economic research on the minimum wage shows that between 1979 and 2012, more than 38 percent of the rise in inequality between the wage paid to the 10th percentile wage (the bottom ten percent of U.S. workers earn this wage or less) and the median wage is due to the minimum wage failing to keep up with the median wage. By indexing the minimum wage to the median wage, policymakers will help prevent widening disparities between those at the bottom and the middle of the wage distribution.

Second, wage indexing allows the minimum wage to rise in ways that the labor market can easily accommodate. Indexing the minimum wage to the general wage level means that roughly the same proportion of workers will earn the minimum wage year after year when the minimum wage rises. As long as underlying wage inequality does not change too much, fixing the distance between the minimum and median wage will keep constant the share of workers earning at or near the minimum wage.

What’s more, because a minimum wage increase will not alter the share of workers earning the minimum, employers will more easily adjust to regular increases in the minimum wage based on wage-indexing—as opposed to the irregular and larger increases typical of the current federal procedure, and many of the state and local procedures, for setting the minimum wage. Indexing to the median wage would require employers to raise wages for roughly the same proportion of their employees each year, whereas failing to index typically results in employers being required to raise wages for a much larger share of their workforces on less predictable basis.

What an indexed minimum wage would look like

Examining how the minimum wage would change over time if it were indexed to other measures of economic activity, such as prices or wages, is fairly straightforward. Immediately after the increase in the federal minimum wage back in 1996 and 1997, Congress could have indexed the new federal minimum wage of $5.15 an hour. Figure 1 shows how the minimum wage would have risen had it been indexed to the median wage or inflation from 1998 to 2014.

Figure 1

Because Congress did not index the minimum to either prices or wages, the federal minimum remained unchanged for a decade before increasing in three successive increases in 2007, 2008, and 2009, to a level in between where it would have been if it had followed the path traced out by either indexing policy. The same figure also illustrates that the federal minimum wage has remained flat now for six years since the 2009 increase.

The median-wage indexed minimum wage is higher today than the minimum wage indexed to the Consumer Price Index because during the late 1990s and early 2000s nominal wages grew faster than inflation, resulting in real wage growth (after accounting for inflation). As a result, the median-index minimum wage would have been more than $8.25 in 2014. The inflation-indexed minimum wage would have been just over $7.60. Either way, the current federal minimum wage is lower than both indexed minimum-wage levels, standing at $7.25 an hour.

View full PDF here alongside all endnotes

We can also consider what the minimum wage would be had we indexed it to the median wage in 1968, which was the high point of the minimum wage relative to the median wage. In 1968, the minimum wage was more than 52 percent of the median wage of full-time workers, whereas in 2014 the minimum wage is about 37 percent of the full-time median wage. If Congress had indexed the minimum wage to the median wage starting in 1968 than the minimum wage in 2014 would have been $10.21—more than 40 percent higher than the current minimum of $7.25.

Indexing the minimum to the median wage in 1998 or 1968 would have obtained substantially different minimum wages in 2014. The $10.21 minimum wage resulting from an increase in 1968 would have been almost 24 percent larger than the $8.26 that would have resulted from an increase in 1998. This underscores the importance of setting the appropriate level of the minimum wage before indexing it to the median wage. The minimum wage will only help a small portion of the workforce if it is set at a low fraction of the median wage and subsequently indexed. Wage indexing only maintains the position of the minimum wage relative to the typical wage, but indexing does not help set the initial level of the minimum wage.

By linking the minimum wage to the median wage, wage indexing keeps the minimum from falling to levels that many consider to be unfairly low or out of step with broader wage growth in the labor market. In addition, economists and political scientists alike recognize that economic fairness—and specifically the relationship between the minimum wage and the overall distribution of wages in the U.S. economy—is a major determinant of what the American public thinks is appropriate minimum wage policy.

There are precedents for wage indexing the minimum wage

Using the median wage as an index is natural to economists because they typically compare the minimum wage to the median wage in order to gauge the strength of the minimum wage. Where the minimum wage lies in the overall distribution of wages across the economy is central to contemporary economic theory. Academic research on so-called wage-spillover effects relies on comparisons of the minimum to the median wage. And when assessing the strength of minimum-wage policies across countries and across time periods, economists contrast national minimum-to-median wage ratios.

Keeping the minimum from slipping away from the typical wage also has policy precedents. In the run-up to increase minimum wages in the late 1980s and early 1990s, congressional bills included provisions to index the minimum wage to 50 percent of the average wage. And in the United Kingdom today there is an independent body called the Low Pay Commission, which advises the government on the appropriate annual minimum wage increase by factoring in the distance of the minimum wage to the to the median wage.

The median wage is the best wage to use as an index

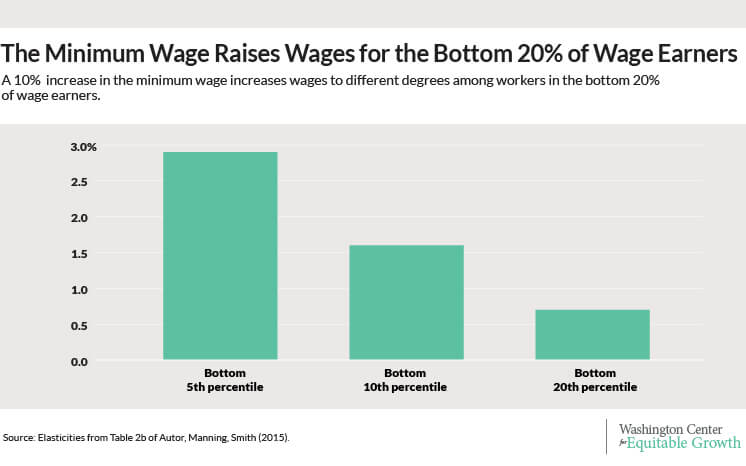

To index the minimum wage to the general wage level, policymakers should use the median hourly wage instead of the average wage. The median wage is a good index because it is unaffected by the minimum wage. Minimum wages in the United States today cover less than ten percent of the workforce. When the minimum wage rises, it directly increases the wages of these low-paid workers. It also indirectly increases the wages of many of the workers who earn above minimum wage but still fall within the bottom 25 percent of wage earners, leaving the middle or median of the wage distribution unaffected.

This approach is better than using the average wage, or mean wage, as the peg for the index. If the minimum is indexed to the mean wage, when minimum-wage workers receive a raise, the average wage rises, which then increases minimum wages, and so on. Over time this process increases the share of the workforce earning the minimum wage, compelling employers to bear continually larger increases in labor costs.

In contrast, if the minimum is increased in line with the median wage, then the share of the workforce earning the minimum wage will remain roughly constant over time. This is because the median wage moves independently of the minimum wage. The benefit of keeping the minimum wage constant as a share of overall wages is that workers competing for low-wage jobs would find demand for their labor among employers equally constant.

In practice, the potential feedback effects from indexing to the average wage are small in a given year, but they may accumulate to economically meaningful sizes over time. Similar feedback effects would also be present in initiatives to index the minimum wage to the Consumer Price Index. If employers pass minimum wage increases onto their customers as price increases, then the minimum wage would indirectly affect the rate of inflation. These inflationary feedback effects, however, would be much smaller than feedback effects of indexing the minimum wage to the average wage because labor costs comprise only a part of the total costs of the production of goods and services.

The lack of any feedback effects from indexing the minimum wage to the median wage is yet another point in favor of this method of raising the minimum wage on an annual basis. Policymakers in Congress should seriously consider such legislation now in order to institute this new way of raising the minimum wage beginning in 2020.