Thanks in large part to the ground-breaking work of Paris School of Economics professor Thomas Piketty, and his co-authors, including University of California-Berkley economics professor Emmanuel Saez, we know that we are living in an era of widening inequality. The share of post-tax-and-transfer income going to the top 1 percent of earners increased from nearly 8 percent in 1979 to about 17 percent in 2007. Over the course of the current economic recovery, the top 1 percent has received 95 percent of all pre-tax income gains—seeing a 31 percent increase in their incomes—while the bottom 99 percent saw a meager 0.4 percent increase.

Economists hypothesize several reasons for this sharp increase in income inequality, among them rising pay for chief executives and other senior executives, increasing returns to superstar workers, the rise of the financial industry, and the decline in top-income tax rates.But this debate is far from over. And the issue is not just income inequality. Economic inequality is on the rise across a variety of dimensions, including wealth. According to research by Saez and Gabriel Zucman, assistant professor of economics at the London School of Economics, the share of wealth owned by the top 0.01 percent has increased 4-fold over in the past 35 years.

Piketty’s data makes the case that the steady accumulation of wealth at the top of the income spectrum is one of the most important ways that income inequality affects our economy. While there may be a theoretical argument for why higher incomes provide greater incentives for individual effort or inventing the next “big thing,” it may also be that, beyond a certain point, income and wealth inequality dampens incentives as the wealthy increasingly seek to preserve their wealth rather than risk it in potentially productive endeavors while the non-wealthy are locked out due to “opportunity hoarding” by those at the top.

One fundamental issue that Piketty’s book, “Capital in the 21st Century,” compels us to consider is the interaction between the flow of income and the stock of wealth. Does today’s flow of income to the very top of the economic ladder calcify into tomorrow’s wealth inequality? After all, the very high incomes that some people earn will allow them to build larger and larger stocks of capital over time.

Do we need to address rising income or wealth inequality in order to save our capitalist economy? How can we do so without hurting the vibrancy of today’s economy? The three essays in this section of our conference report—by UC-Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez, Michael Ettlinger, founding director of the University of New Hampshire Carsey School of Public Policy, and Northwestern University sociology PhD candidate Fiona Chin—discuss the state of top incomes, the consequences of their rise, and possible policies to promote more widely shared economic growth. —Heather Boushey

The Explosion of U.S. Income and Wealth Inequality

by Emmanuel Saez

In the United States today, the share of total pre-tax income accruing to the top 1 percent has more than doubled over the past five decades. The wealthy among us (families with incomes above $400,000) pulled in 22 percent of pre-tax income in 2012, the last year for which complete data are available, compared to less than 10 percent in the 1970s. What’s more, by 2012 the top 1 percent income earners had regained almost all the ground lost during the Great Recession of 2007-2009. In contrast, the remaining 99 percent experienced stagnated real income growth—after factoring in inflation—after the Great Recession.

Another less documented but equally alarming trend has been the surge in wealth inequality in the United States since the 1970s. In a new working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Gabriel Zucman at the London School of Economics and I examined information on capital income from individual tax return data to construct measures of U.S. wealth concentration since 1913. We find that the share of total household wealth accrued by the top 1 percent of families— those with wealth of more than $4 million in 2012—increased to almost 42 percent in 2012 from less than 25 percent in the late 1970s. Almost all of this increase is due to gains among the top 0 .1 percent of families with wealth of more than $20 million in 2012. The wealth of these families surged to 22 percent of total household wealth in the United States in 2012 from around 7.5 percent in the late 1970s.

The flip side of such rising wealth concentration is the stagnation in middle-class wealth. Although average wealth per family grew by about 60 percent between 1986 and 2012, the average wealth of families in the bottom 90 percent essentially stagnated. In particular, the Great Recession reduced their average family wealth to $85,000 in 2009 from $130,000 in 2006. By 2012, average family wealth for the bottom 90 percent was still only $83,000. In contrast, wealth among the top 1 percent increased substantially over the same period, regaining most of the wealth lost during the Great Recession.

For both wealth and income, then, there is a very uneven recovery from the losses of the Great Recession, with almost no gains for the bottom 90 percent, and all the gains concentrated among the top 10 percent, and especially the top 1 percent. How can we explain such large increases in income and wealth concentration in the United States and what should be done about it?

Contrary to the widely held view, we cannot blame everything on globalization and new technologies. While large increases in income concentration occurred in other English-speaking countries such as the United Kingdom or Canada, other developed-nation members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, such as those in continental Europe or Japan, experienced far smaller increases in income concentration. At the same time, income tax rates on upper income earners have declined significantly since the 1970s in many OECD countries, particularly in English-speaking ones. Case in point: Top marginal income tax rates in the United States and the United Kingdom were above 70 percent in the 1970s before President Ronald Reagan’s administration and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s government drastically cut them by 40 percentage points within a decade.

New research I published this year with Paris School of Economics professor Thomas Piketty and Stefanie Stantcheva at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology shows that, across 18 OECD countries with sufficient data, there is indeed a strong correlation between reductions in top tax rates and increases in the top 1 percent’s share of pre-tax income from the 1960s to the present. Our research shows that the United States experienced a 35-percentage point reduction in its top income tax rate and a ten-percentage point increase in the share of pre-tax income earned by the top 1 percent. In contrast, France and Germany saw very little change in their top tax rates and the share of pre-tax income accrued by the top 1 percent over the same period.

The evolution of top tax rates is a good predictor of changes in pre-tax income concentration. There are three scenarios to explain the strong response of top pre-tax incomes to top tax rates. They have very different policy implications and can be tested in the data.

First, higher top tax rates may discourage work effort and business creation among the most talented—the so-called supply-side effect of higher taxes. In this scenario, lower top tax rates would lead to more economic activity by the rich and hence more economic growth. Yet the overwhelming evidence shows that there is no correlation between cuts in top tax rates and average annual real (inflation-adjusted) GDP-per-capita growth since the 1960s. Countries that made large cuts in top tax rates, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, have not grown significantly faster than countries that did not, such as Germany and Denmark.

Second, higher top tax rates could increase tax avoidance. In that scenario, increasing top rates in a tax system riddled with loopholes and tax avoidance opportunities is not productive. A better policy would be first to close loopholes in order to eliminate most opportunities for tax avoidance and only then increase top tax rates. Conservative commentators argue that the surge in pre-tax incomes discussed above could be indicative of tax avoidance in the 1970s, when top earners were presumably hiding a large fraction of their income amid high taxes.

If this tax avoidance scenario were true, then charitable giving among top earners should have decreased once top tax rates were cut. After all, charitable giving is tax deductible and thus is more advantageous precisely when top tax rates are high. In fact, charitable giving among the rich surged pretty much in the same proportion as their reported incomes over the past several decades. If the rich are able to give so much more today than in the 1970s, it must be the case that they are truly richer.

Third, while standard economic models assume that pay reflects productivity, there are strong reasons to be skeptical, especially at the top of the income ladder where the actual economic contribution of managers working in complex organizations is particularly difficult to measure. In this scenario, top earners might be able partly to set their own pay by bargaining harder or influencing executive compensation committees. Naturally, the incentives for such “rent-seeking” are much stronger when top tax rates are low.

In this scenario, cuts in top tax rates can still increase the share of total household income going to the top 1 percent at the expense of the remaining 99 percent. In other words, tax cuts for the wealthiest stimulate rent-seeking at the top but not overall economic growth—the key difference from the supply-side scenario that justified tax cuts for high income earners in the first place.

Up until the 1970s, policymakers and public opinion probably considered—rightly or wrongly—that at the very top of the income ladder pay increases reflected mostly greed or other socially wasteful activities rather than productive work. This is why policymakers were able to set marginal tax rates as high as 80 percent in the United States and the United Kingdom. The Reagan-Thatcher supply side revolutions succeeded in making such top tax rate levels unthinkable, yet after decades of increasing income concentration alongside mediocre economic growth since the 1970s followed by the Great Recession, a rethinking of that supply side narrative is now underway.

Zucman and I show in our new working paper that the surge in wealth concentration and the erosion of middle class wealth can be explained by two factors. First, differences in the ability to save by the middle class and the wealthy means that more income inequality will translate into more inequality in savings. Upper earners will naturally save relatively more and accumulate more wealth as income inequality widens.

Second, the saving rate among the middle class has plummeted since the 1980s, in large part due to a surge in debt, in particular mortgage debt and student loans. With such low savings rates, middle class wealth formation is bound to stall. In contrast, the savings rate of the rich has remained substantial.

If such trends of growing income inequality and growing disparity in savings rates between the middle class and rich persist, then U.S. wealth inequality will continue to increase. The rich will be able to leave large estates to their heirs and the United States could find itself becoming a patrimonial society where inheritors dominate the top of the income and wealth distribution as famously pointed out by Piketty in his new book “Capital in the 21st Century.”

What should be done about the rise of income and wealth concentration in the United States? More progressive taxation would help on several fronts. Increasing the tax rate as incomes rise helps curb excessive and wasteful compensation of top income earners. Progressive taxation of capital income also reduces the rate of return on wealth, making it more difficult for large family fortunes to perpetuate themselves over generations. Progressive estate taxation is the most natural tool to prevent self-made wealth from becoming inherited wealth. At the same time, complementary policies are needed to encourage middle class wealth formation. Recent work in behavioral economics by Richard Thaler at the University of Chicago and Cass Sunstein at Harvard University shows that it is possible to encourage savings and wealth formation through well-designed programs that nudge people into savings. –Emmanuel Saez is a professor of economics and Director of the Center for Equitable Growth at the University of California-Berkeley

Addressing Economic Inequality Requires a Broad Set of Policies and Cooperation

by Michael Ettlinger

There are any number of policies suggested by policymakers, academics and commentators for addressing economic inequality. A representative sample would include tax redistribution, improving education, raising the minimum wage, direct government job creation, employer hiring incentives, subsidized child care, better retirement security, a stronger social safety net, direct middle- and low-income subsidies, ending the socialization of environmental degradation, aggressive financial market regulation, stronger trade unions, more investment in public goods (paid for by the better off), socially responsible trade policy, immigration reform, corporate governance changes, and campaign finance reform.

That’s certainly a formidable list, but interestingly most analysts and advocates who care about economic inequality focus on just one or two of these—typically offering a concise, but ultimately unsatisfying recipe. Given the rapidly rising levels of inequality, when one reads the typical, short, policy agenda, it’s hard not to have a feeling of ennui—a sense that the solution offered falls well short of what’s needed to solve the problem or is completely impractical.

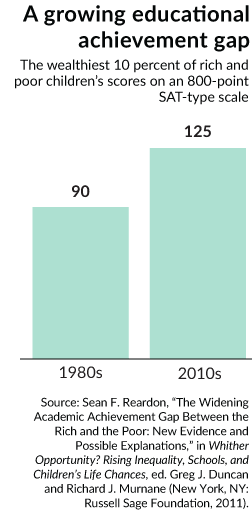

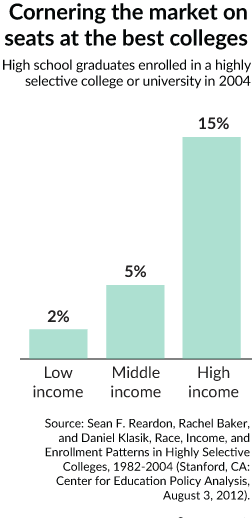

It is, for example, hard to believe that better educational opportunities is the complete answer. Improving education has huge virtue in terms of economic advancement at the individual level, creating opportunity, personal fulfillment, and overall economic growth. But, aside from anything else, at the rate we’re going, we’ll have again doubled our level of inequality by the time substantial numbers of people are likely to benefit from improved education. And it’s not like we’ve licked how exactly to improve education or that it’s clear that improved education solves the problem.

After all, if the result of boosting educational attainment is simply more competition for a slowly increasing number of jobs that require further education, then the effect might primarily be that different people are on the winning and losing ends of inequality, not a lessening of inequality itself—at least from a global perspective. And the historical record is not encouraging. So, we should improve education, but we shouldn’t count on it as the silver bullet for addressing inequality.

There are other policies, of course, that are blunter instruments and clearly could fundamentally change the distribution of income and wealth. Taxes are the most clear cut example. If we take a sizable portion of the income of the wealthy and, one-way-or-another, distribute it to everyone else, inequality would, unequivocally, be reduced (call this the Sherwood Forest approach). But redistribution on that scale is unlikely and, at truly the scale that would be needed to reduce the levels inequality to what it was even a few years ago, would probably be damaging to the overall economy. While there is ample evidence that the moderately higher levels of income tax on the well off are not the economic disaster sometimes claimed, addressing extreme economic inequality exclusively through the income tax could get us to the point at which higher taxes do cause harm. As with education, raising income taxes on the wealthy is not, alone, the answer.

“Wealth” or “capital” taxes on the assets of the better off, another favored approach, face a number of practical limitations. One problem in the United States is that a federal wealth tax would almost certainly require an amendment to the constitution. But even aside from that “technicality,” there is a limit to what one could reasonably expect to accomplish with a wealth tax.

One of the virtues of an income tax is that it taxes money going between two parties who both are typically required to inform the tax authorities of the transaction—so to outright cheat on taxes requires the complicity of at least two people. It happens, but the requirement of trust limits it. Wealth, in contrast, can be held without active engagement of another party.

Another virtue of an income tax is that if the transaction is honest then the dollar amount involved is usually clear-cut. That is less true for a tax on wealth. Assets held in publicly traded corporations or real estate in areas where there are frequent land deals are relatively easy. But the valuation of closely held corporations, let alone art and obscure intellectual property rights, can be extremely difficult—and one can count on more wealth ending up in those forms if a substantial wealth tax were put in place. A very small wealth tax would not necessarily spark this sort of tax avoidance. A substantial one would.

I can make similar arguments for almost the entire list I started with. Even if one believes that the minimum wage is too low, most everyone would agree that it can be too high. Even if one believes that our trade regimes are a factor in increasing inequality and that reforms are needed, overly restrictive policies would be counterproductive. Even if you believe that the outsized incomes from Wall Street are a consequence of power and influence—not genuine contributions to our overall prosperity—the national economy would surely be hurt if we tried to address economic inequality purely through restraints on the financial sector.

If you didn’t have ennui when you started reading this you probably do now. But the point isn’t that it’s impossible to address income inequality. The point is that it’s going to take a range of approaches. And, arguably, a range of approaches is easier to accomplish than trying to put all of one’s eggs in a single basket. If the whole solution doesn’t depend on a confiscatory tax on the wealthy, or vastly increasing educational attainment, or world-wide consensus on a socially responsible, equitable, trade agreement—but instead on incremental change in range of areas—that is a much less daunting task.

There are agreements to be had in many of these areas. None of those individual policies will be at the scale needed to address inequality in a meaningful way, but together they can add up to make a difference.

There are reasons to do this. Extreme inequality leaves many people having harder lives than is necessary while, at the other end of the spectrum, personal wealth can reach a point where its growth does little to improve the lives of its beneficiaries—with the overall result being a net reduction in the aggregate quality of life. And there are real dangers to our society of such severe stratification. It’s an issue that is going to require a broad range of effort and cooperation around the world to address. But it’s achievable if we don’t try to accomplish it with just one or two highly contested policies. — Michael Ettlinger is the founding director of the Carsey School of Public Policy at the University of new Hampshire

What the Wealthy Know and Believe About Economic Inequality

by Fiona Chin

The wealthiest one percent among us in the United States are pulling away from everyone else, a trend documented by numerous economists and highlighted often by the media. Despite all this attention on inequality, there is a dearth of empirical research on what the wealthy know and believe to be true about this trend.

Recent research on social stratification and mobility in our country examines the beliefs of ordinary Americans about the growing wealth and income gaps, but few academics are talking directly to the wealthiest Americans about their own perceptions. It is notoriously difficult to interview wealthy subjects. It is hard to find them, given their scarcity in the population. Once you identify possible subjects, it is hard to gain their cooperation, particularly when discussing topics they find uncomfortable, such as income and wealth inequality.

How the very affluent view economic inequality is important because what they know and think influences how they interact with our political leaders responsible for translating these views into public policies. If policymakers respond disproportionately to the affluent and the majority of the wealthy do not favor government programs to ameliorate inequality then it is especially important for scholars and policy experts to learn what ideas and preferences the wealthy embrace. In contrast, if the majority of the very affluent favor steps to rectify the wealth and income gaps, then policymakers can consider enacting programs that are favored more by the general public.

I study wealthy Americans to find out what they believe about income and wealth inequality.1 My data come from two sources. The first is the Survey of Economically Successful Americans and the Common Good, or SESA, which was pioneered by Northwestern University political science professor Benjamin Page and Vanderbilt University political science professor Larry Bartels and funded by the Russell Sage Foundation.2 NORC at the University of Chicago conducted the survey in 2011. Respondents had an average of $14 million in household wealth (median of $7.5 million), making the sample representative of the wealthiest one-to-two percent of Chicago-area residents.

Most national surveys with representative samples capture very few respondents from the top of the wealth distribution. While it targets the Chicago metropolitan area, SESA is among the very few data sets on the wealthy and includes questions on a variety of topics, from economic mobility to taxes, retirement, philanthropic and charitable volunteering and giving, and other areas. As a survey, however, SESA was limited in the depth to which respondents could answer any particular question.

Upon reviewing the original survey sheets with interviewer notations in the margins, I found that the wealthy were eager to express more nuance than closed-ended survey responses provided. To complement the survey data with more detail, I am compiling a second source of information by conducting in-depth interviews with economically successful Americans from across the country. These interviews focus much more specifically on subjects’ beliefs about economic inequality and mobility, politics, and public policy.

As of August 2014, I have conducted 89 interviews ranging from 45 minutes to three hours in length. I spoke with top income earners and top wealth holders, who I recruited based on the chain-referral method. Although my sample is not statistically representative, this methodology has allowed me to collect data on the beliefs of wealthy Americans from different geographic regions and backgrounds. Interview respondents had an average of $8.2 million in household wealth (median of $4.7 million). The interview sample was not as wealthy as the SESA sample overall, but more than half of my interviewees were within the top one percent of the income or wealth distributions. Interview subjects were from 18 different metropolitan areas across 15 states and the District of Columbia and worked in a variety of occupations and industries.

Despite the methodological differences, the interview questions that duplicated SESA questions yielded very similar patterns of answers. My research is on-going, but I have some preliminary results to share, with the important caveat that I am continuing to analyze my data and hope to conduct approximately ten more interviews.

The wealthy are aware of economic inequality and recognize that it has grown in recent decades. In the SESA data and my own in-depth interviews, the vast majority of respondents knew that income inequality is larger today than it was 20 years ago. They also tended to express a desire for a lower level of income inequality. Approximately two-thirds of respondents believed that income differences in our society are too large.

The wealthy also recognize that the distribution of wealth across society is very skewed. In fact, they tend to overestimate the proportion of wealth held by the top one percent. Based on the SESA data and my preliminary interviews, the median perception of the respondents so far was that the top one percent hold approximately half of all U.S. wealth. (According to New York University economist Edward Wolff, the wealthiest one percent held a 35 percent share of the country’s household net worth, as of 2007.3) In my interviews, I also probe subjects about how large a share the wealthiest one percent “ought” to hold. Only about two-fifths of interview respondents believed that the wealthiest one percent ought to hold less.

In short, both survey and interview respondents tended to agree that income inequality is too high. But my interview data show that the wealthy did not necessarily believe that there should be less wealth inequality.

As much as the wealthy appear to be aware of growing economic inequality, they did not necessarily favor any kind of public intervention to remedy or ameliorate the trend. In fact, the wealthiest SESA respondents favored cutting back federal government programs such as Social Security, job programs, health care, and food stamps. Only 17 percent of SESA respondents thought that the government should “redistribute wealth by heavy taxes on the rich.”

Among my interviewees, very few were in favor of raising taxes to redress economic disparities, although a minority supported public intervention in the form of job training and other programs aimed at increasing economic opportunity. In general, many interview subjects were very pessimistic about the future of inequality trends and did not foresee any slow down in the growing bifurcation between the wealthy and the rest of society.

As a group, then, the wealthy are well informed about current events and public affairs, according to my preliminary interviews and the SESA data. They pay attention to the news and are very politically active, so understanding and considering their preferences are important. My preliminary findings indicate two emerging patterns: The wealthy know that economic inequality is rising, but they do not agree that anything should or can be done to reverse the trend. My analysis is at an early stage, and much more research must be done in this arena in order to inform a productive dialogue between scholars and policymakers. –Fiona Chin is Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Northwestern University and a graduate research assistant at the Institute for Policy Research