Kevin Warsh and Michael Spence attack Ben Bernanke and his policy of quantitative easing, which they claim “has hurt business investment.”

I score this for Bernanke: 6-0, 6-0, 6-0.

In fact, I do not even think that Spence and Warsh understand that one is supposed to have a racket in hand when one tries to play tennis. As I see it, the Fed’s open-market operations have produced more spending–hence higher capacity utilization–and lower interest rates–has more advantageous costs of finance–and we are supposed to believe that its policies “have hurt business investment”?!?!

Michael Spence and Kevin Warsh: The Fed Has Hurt Business Investment: “Bernanke[‘s view]… may well be true according to economic textbooks…

…But textbooks presume the normal conduct of policy and that the prices of financial assets like stocks and bonds are broadly consistent with expectations for the real economy. Nothing could be further from the truth in the current recovery…. Earnings of the S&P 500 have grown about 6.9% annually… pales in comparison to prior economic expansions… half of the profit improvement… from… share buybacks. So the quality of earnings is as deficient as its quantity…. Extremely accommodative monetary policy… $3 trillion in… QE pushed down long-term yields and boosted the value of risk-assets…. Business investment in the real economy is weak. While U.S. gross domestic product rose 8.7% from late 2007 through 2014, gross private investment was a mere 4.3% higher. Growth in nonresidential fixed investment remains substantially lower than the last six postrecession expansions….

As I have said before and say again, weakness in overall investment is 100% due to weakness in housing investment. Is there an argument here that QE has reduced housing investment? No. Is nonresidential fixed investment below where one would expect it to be given that the overall recovery has been disappointing and capacity utilization is not high? No. The U.S. looks to have an elevated level of exports, and depressed levels of government purchases and residential investment. Given that background, one would not be surprised that business investment is merely normal–and one would not go looking for causes of a weak economy in structural factors retarding business investment. One would say, in fact, that business investment is a relatively bright spot.

Yes, businesses have been buying back shares. How would the higher interest rates and higher risk spreads in the absence of QE retard that? They wouldn’t. Yes, earnings growth from business operations over the past five years has been slower than in earlier expansions. How has QE dragged on earnings growth. It hasn’t.

Efforts by the Fed to fill near-term shortfalls in demand… have shown limited and diminishing signs of success. And policy makers refuse to tackle structural, supply-side impediments to investment growth, including fundamental tax reform.

And the Federal Reserve’s undertaking of QE has hampered efforts to engage in “fundamental tax reform” how, exactly? Is an argument given here? No, it is not.

We believe that QE has redirected capital from the real domestic economy to financial assets…. How has monetary policy created such a divergence between real and financial assets?

OK: Now there is a promise that there will be some meat in the argument.

How do Spence and Warsh say QE has reduced corporate investment? Let’s look:

First, corporate decision-makers can’t be certain about the consequences of QE’s unwinding on the real economy… [that] translates into a corporate preference for shorter-term commitments–that is, for financial assets….

Let’s see: when QE is unwound, asset prices are likely to fall. The period of QE may have boosted the economy and created a virtuous circle–in which case unwinding QE will still leave asset prices higher than they would have been in its absence. Unwinding QE may return asset supplies and demands to where they would have been if it had never been undertaken–in which asset prices will be what they would have been in its absence. Is there a story by which first winding and then unwinding QE leaves asset prices afterwards lower than in QE’s absence? Is there? Anyone? Anyone? Bueller?

Without an argument that the round-trip will leave lower asset prices than the absence of QE, this “uncertainty” argument is incoherent. No such argument is offered.

And I cannot envision what such an argument would be.

The financial crisis taught an important lesson…. Illiquidity can be fatal….

So in the absence of QE people would have forgotten about the financial crisis and would be eager to get illiquid–no, wait a minute! This is not an argument that QE has depressed business investment.

QE reduces volatility in the financial markets, not the real economy…. Much like 2007, actual macroeconomic risk may be highest when market measures of volatility are lowest…

QE reduces volatility in financial markets by making some of the risk tolerance that was otherwise soaked up bearing duration risk free to bear other kinds of risk. That is what it is supposed to do. With more risk tolerance available, more risky real activities will be undertaken–and so microeconomic risk will grow. A higher level of activity with more risky enterprises being undertaken is the point of QE. To say that it pushes up macroeconomic risk is to say that it is doing its job, isn’t it? If that isn’t its job, then there needs to be an argument to that effect, doesn’t there? I do not see one.

QE’s efficacy in bolstering asset prices may arise less from the policy’s actual operations than its signaling effect…

The originator of the idea of signaling equilibrium thinks that such a thing is bad? If QE has effects because it is an informative signal, then it is a good thing as long as its dissipative costs are not large. Is an argument offered that its dissipative costs are large? No. Is there reason to think that its dissipative costs are large? No.

We recommend a change in course. Increased investment in real assets is essential to make the economic expansion durable.

And unwinding QE more rapidly accomplishes this how, exactly? In the absence of QE increased investment in real assets would be higher why, exactly?

If you set out to take Vienna, take Vienna. If you are going to argue that QE has reduced real business investment, argue that QE has reduced real business investment. I see no such argument anywhere in the column.

So Warsh and Spence should not be surprised at my reaction: “Huh!?!?!” and “WTF!?!?!?!?”

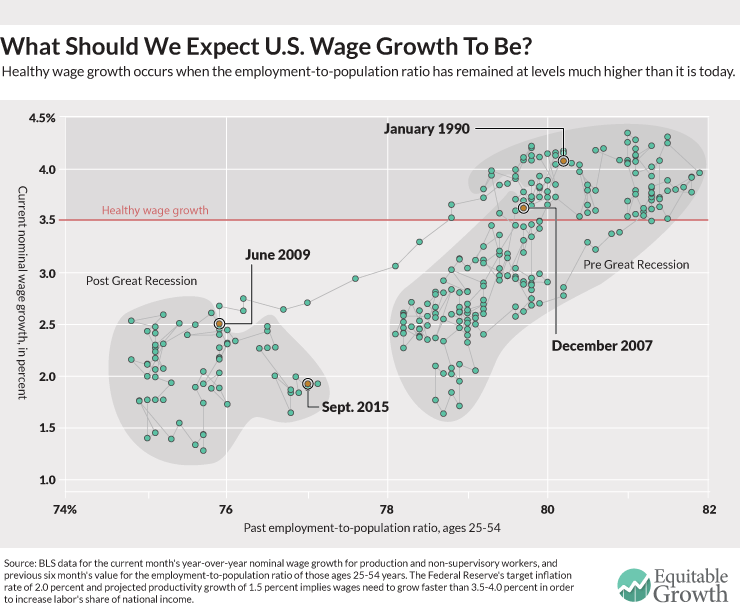

The graph shows the relationship between wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers, and the employment rate for prime-age workers six months prior. It clearly shows that when the labor market is tighter (when the employment rate is higher), wage growth is stronger.

The graph shows the relationship between wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers, and the employment rate for prime-age workers six months prior. It clearly shows that when the labor market is tighter (when the employment rate is higher), wage growth is stronger.