- : Five Simple Formulas

- : The Fear Factor in Global Markets

- : More on the Political Trilemma of the Global Economy

- : Machinations of Wicked Men

- : The Enduring Employment Impact of Your Great Recession

- : Interest, Capital, MRScc=(1+r)=1+(MPK/MRTci)+(dMRTci/dt)/MRTci

Category: Equitablog

Must-read: Jared Bernstein: “Five Simple Formulas”

Must-Read: : Five Simple Formulas: “Here are five useful, simple… inequalities…

…Each one tells you something important about the big economic problems we face today or, for the last two formulas, what we should do about them. And when I say ‘simple,’ I mean it…. r>g… that if the return on wealth, or r, is greater than the economy’s growth rate, g, then wealth will continue to become ever more concentrated….

S>I… Bernanke’s imbalance…. Larry Summers’ ‘secular stagnation’ concerns offer a similar, though somewhat more narrow, version. For the record, I think this one is really serious (I mean, they’re all really serious, but relative to r>g, S>I is underappreciated)…. In theory, there are key mechanisms in the economy that should automatically kick in and repair the disequilibrium…. Central bankers, like Bernanke and Yellen, tend to discuss S>I and the jammed mechanisms just noted, as ‘temporary headwinds’ that will eventually dissipate (Summers disagrees). But while it has jumped around the globe—S>I is more a German thing right now than a China thing (Germany’s trade surplus is 8 percent of GDP!)—the S>I problem has lasted too long to warrant a ‘temporary’ label….

u>u… Baker/Bernstein’s slack attack…. For most of the past few decades—about 70 percent of the time, to be precise—u has been > than mainstream estimates of u, meaning the job market has been slack…. From the 1940s to the late 1970s, u*>u only 30 percent of the time, meaning the job market was mostly at full employment….

g>t… [Richard] Kogan’s cushion…. For most of the years that our country has existed (he’s got data back to 1792!), the economy’s growth rate (g again) has been greater than the rate the government has to pay to service its debt, which I call t. Kogan calls it r since it’s a rate of return, but it’s not the same r as in Piketty (which is why I’m calling it t)….

0.05>h… the DeLong/Summers low-cost lunch…. When the private economy is weak, government spending can be a very low-cost way to lift not just current jobs and incomes, but future growth as well…. The ‘h’ stands for hysteresis, which describes the long-term damage to the economy’s growth potential when policy neglect allows depressed economies to persist over time…. As an increase in current output by a dollar raises future output by at least a nickel, the extra spending will be easily affordable. But how do we know if 0.05>h? In a follow-up paper for CBPP’s full-employment project, D&S, along with economist Larry Ball, back out a recent number for h that amounts to 0.24, multiples of the 0.05 threshold, and evidence that, at least recently, h>0.05…

Must-read: Ken Rogoff: “The Fear Factor in Global Markets”

Must-Read: This, by the very-sharp Ken Rogoff, seems to me to be simply wrong. If “the supply side, not lack of demand, is the real constraint in advanced economies” then we would live in a world in which inflation would be on a relatively-rapid upswing right now. Instead, we live in a world in which Global North central banks are persistently and continually failing to meet their rather-modest targets for inflation. If a fear of supply disruptions or supply lack were ruling markets, then people in markets would be heavily betting on an upsurge of inflation and we would see that. But we don’t. What am I missing here?

: The Fear Factor in Global Markets: “There are some parallels between today’s unease and market sentiment in the decade after World War II…

…In both cases, there was outsize demand for safe assets. (Of course, financial repression also played a big role after the war, with governments stuffing debt down private investors’ throats at below-market interest rates.)… People today need no reminding about how far and how fast equity markets can fall…. The idea is that investors become so worried about a recession, and that stocks drop so far, that bearish sentiment feeds back into the real economy through much lower spending, bringing on the feared downturn. They might be right, even if the markets overrate their own influence on the real economy. On the other hand, the fact that the US has managed to move forward despite global headwinds suggests that domestic demand is robust. But this doesn’t seem to impress markets….

The most convincing explanation… is… that markets are afraid that when external risks do emerge, politicians and policymakers will be ineffective in confronting them. Of all the weaknesses revealed by the financial crisis, policy paralysis has been the most profound. Some say that governments did not do enough to stoke demand. Although that is true, it is not the whole story. The biggest problem burdening the world today is most countries’ abject failure to implement structural reforms. With productivity growth at least temporarily stuck in low gear, and global population in long-term decline, the supply side, not lack of demand, is the real constraint in advanced economies…

Must-read: Dani Rodrik: “More on the Political Trilemma of the Global Economy”

Must-Read: I find myself more on Martin Sandbu’s side than that of the very-sharp Dani Rodrik in this debate. This is largely, I think, because Dani remains at too abstract a level. The commitment of foreign trading partners to “openness”, whatever that turns out to mean in practice, enlarges domestic political and economic opportunities in some directions. But one’s own government’s reciprocal commitment to “openness”, whatever that turns out to mean in practice, restricts domestic political and economic opportunities in different directions. How much should a government and a people value the gains in the first set of directions? How much should a government and a people regret the loss in the second set?

These are questions that must be answered pragmatically. The devil is in the details. And ideologies–either Friedmanesque rants that globalization is always good or Trumpist rants that “we” are always outmaneuvred in trade deals by shifty foreigners–seem to me profoundly unhelpful here. And so the word “globalization” becomes an obstacle rather than an aid to thought…

: More on the Political Trilemma of the Global Economy: “Here are [Martin] Sandbu’s main points and my take on them…

…”if economic integration limits a national democracy’s room for manoeuvre, does it limit a national dictatorship’s opportunities any less?” I think Sandbu’s point is true for some dictatorships, but not all. Today the prevailing worry of progressives is that an oligarchy of financiers, investors, and skilled professionals has captured the polity and is using globalization as a way of imposing its policy priorities. What globalization does for these groups is actually to expand their political opportunities, rather than constrain them…. [In] a democracy… the electorate can decide on their own path… even when it may conflict what a narrowly based, internationally mobile elite want–and that is what hyper-globalization restricts….

“We should beware of conflating economic integration with technocracy.”… In practice, globalization is used to impose a particular technocratic set of rules serving the interests of particular groups. That it need not do so is a valid point for globalization in general, as long as don’t take it as far as hyper-globalization….

“Is [there] necessarily a loss of democracy when the rules are set internationally while most democratic institutions remain nationally rooted[?]… Negotiating rules together is an exercise of national self-determination, not its abrogation.”… As long as we are not trying to eliminate every transaction cost to international trade and investment, there are multiple models of globalization… leaving plenty of space for countries to devise their own social and economic arrangements….

The fact that an international rule is negotiated and accepted by a democratically elected government does not inherently make that rule democratically legitimate…. There are many ways in which globalization actually harms rather than enhances the quality of democratic deliberation. For example, preferential or multilateral trade agreements are often simply voted up or down in national parliaments with little discussion, simply because they are international agreements. Globalization-enhancing global rules and democracy-enhancing global rules may have some overlap; but they are not one and the same thing…. International commitments can be used to tie the hands of governments in both democratically legitimate and illegitimate ways…. The constraints really bind in the presence of a hyper-globalization/deep-integration model (a la Eurozone)…

Must-read: Jonathan Kirshner: “Machinations of Wicked Men”

Must-Read: May I say that I do not understand what the entire point of labeling Henry Kissinger an “idealist” would be?

Of course, I also do not understand what the point of the idealist-realist divide is. Everyone has hopes for a better world, and reaches for them. Everyone has to grapple with the world as it is.

The true divisions among international relations specialists are, I think, twofold:

- The division between those who are being smart and those who are being stupid.

-

The division between (i) those who believe that international relations is non-cooperative zero sum and that one’s purpose is to advance the interests or one’s own nation-state or ethnolinguistic grouping; and (ii) those who believe that international relations is cooperative and positive-sum and that trust via favors with the hope of their subsequent return via gift-exchange is worth building.

Smart vs. stupid; and nationalist vs. cosmopolitan.

Kissinger is, I think, an often- (as in his Nuclear Weapons and American Foreign Policy) but not always-stupid nationalist.

: Machinations of Wicked Men: “[Niall Ferguson’s] central claim—Kissinger the idealist—is… wrong. Simply, plainly, fundamentally, and exactly wrong…

…Do we really need nearly a thousand new pages on Kissinger, and on that part of his life before he joined the Nixon White House?… Much of it is drudgery, as the book also has the tiresome habit of abandoning the narrative thread to introduce ad hominem attacks and petty, provocative asides…. Even for a commissioned biography, the rose-tinted presentation of Kissinger presents a new standard…. Ferguson acknowledges that Kissinger was ‘reputed to be arrogant,’ but chooses to emphasize instead, at length, Henry’s devotion to his dog. The book reads as if no slight against Kissinger, real or imagined, might go unanswered….

Classical realism… sees international politics as characterized by the clash of interests… is properly associated with a brooding, deeply pessimistic streak based on assumptions about humanity’s enduring potential for barbarism, the looming danger of war, and other hazards smoldering just below a thin crust of civilization…. With Morgenthau, Kissinger dissents from the ‘can-do’ idea that science, progress, and problem solving can overcome the perennial and intractable clashes of international politics. Alongside Kennan, Kissinger bemoans the foreign policy practice of democracies and especially of the United States, with its tendency to swing wildly between under-attentive naïveté and overzealous crusading. Both are perceived as dangerous, and neither well suited to advance the national interest. This is classical realism….

Kissinger betrayed the trust of Humphrey’s men, passing on information to Nixon’s camp about the Paris peace talks between Washington and Hanoi. Nixon was concerned that a breakthrough at the talks might be an ‘October surprise’ that would cost him the close election, and evidence shows that Nixon indeed attempted to undermine those talks. Ken Hughes’s Chasing Shadows (2014) is the best account of this sordid affair. Ferguson addresses this affair with a diversion, arguing vociferously that the information Kissinger passed along didn’t amount to much. But these claims are irrelevant in taking the measure of the man. Kissinger proved his value to Nixon by taking such outrageous, and, it must be said, shameful risks…. He named Kissinger his national security advisor, and Rocky handed him a $50,000 check (equivalent to $325,000 today) as a parting gift….

Isaacson records that… ‘at least thirteen close relatives of Kissinger were sent to the gas chambers or died in concentration camps,’ including his father’s three sisters. Ferguson describes in detail how as a young American GI, Kissinger arrived at the Ahlem concentration camp: ‘Wherever they turned, the incredulous soldiers encountered new horrors.’ About thirty years later, discussing with Nixon the treatment of Jews in the Soviet Union, Kissinger volunteered, ‘If they put Jews into gas chambers in the Soviet Union, it is not an American concern. Maybe a humanitarian concern.’ Maybe.

Must-read: Danny Yagan: “The Enduring Employment Impact of Your Great Recession”

Must-Read: : The Enduring Employment Impact of Your Great Recession: “In the cross section, employment rates diverged across U.S. local areas 2007-2009…

…and–in contrast to history–have barely converged [since]…. I… use administrative data to compare two million workers with very similar pre-2007 human capital: those who in 2006 earned the same amount from the same retail firm, at establishments located in different local areas. I find that, conditional on 2006 firm-x-wages fixed effects, living in 2007 in a below-median 2007-2009-fluctuation area caused those workers to have a 1.3%-lower 2014 employment rate…. Location has affected long-term employment and exacerbated within-skill income inequality. The enduring employment impact is not explained by more layoffs, more disability insurance enrollment, or reduced migration. Instead, the employment outcomes of cross-area movers are consistent with severe-fluctuation areas continuing to depress their residents’ employment. Impacts are correlated with housing busts but not manufacturing busts, possibly reconciling current experience with history. If recent trends continue, employment rates are estimated to converge in the 2020s–adding up to a relative lost decade for half the country.

Must-read: Nick Rowe: “Capital Theory and the Distribution of Income”

Must-Read: Nick Rowe provides a very brief masterclass in “capital theory”, which is really the theory of the price system not just at a point in time but over time. (Cf. (1975): Capital Theory and the Distribution of Income.) Needless to say, there is no presumption that there is only one equilibrium vector for the intertemporal price system. And there is no presumption that problems of aggregation for commodities called “capital” is any easier than problems of aggregation for commodities called “labor” or “services” or “nondurable goods”. (The question of whether the problems of aggregation for commodities called “capital” is any more difficult than for any other not-completely-unreasonable grouping is left as an exercise):

: Interest, Capital, MRScc=(1+r)=1+(MPK/MRTci)+(dMRTci/dt)/MRTci: “The slope of the indifference curve [is] the Marginal Rate of Intertemporal Substitution…

…between consumption this year and consumption next year. Call it MRScc…. The slope of the PPF [is] the Marginal Rate of Intertemporal Transformation, between consumption this year and consumption next year. Call it MRTcc. The equilibrium condition is: MRScc = (1+r) = MRTcc…. We don’t need ‘capital’, or its marginal product, to determine the rate of interest…. Where is ‘capital’ in this model? And where is the Marginal Product of Kapital? Does MPK determine r? Does MPK=r? ‘No’, is the answer to both those questions.

The equilibrium condition is MRScc=(1+r)=MRTcc. MPK is one of the things, but not the only thing, that affects MRTcc. And MRTcc is equal to (1+r), but it does not determine (1+r)…. MPK is defined as the extra apples produced per extra existing machine, holding technology and other resources constant, and holding the production of new machines constant. If we move along the PPF between consumption and investment this year, we will have a bigger stock of capital goods next year, which will shift out next year’s PPF. MPK tells us how much it shifts out, per extra machine….

If capital exists, the real rate of interest is equal to, but not determined by, the Marginal Product of Kapital divided by the real price of the machine, plus the capital gains from appreciation of the real price of machines…. Rather than saying ‘MPK determines r’, it would be more true to say ‘MRScc determines r, which determines the prices of capital goods’. And the only thing wrong with saying that is that is that MRScc… depends on the expected growth rate of consumption, which in turn depends on our ability to divert resources to producing extra capital goods instead of consumption goods, and the productivity of those extra capital goods…

Weekend reading: “Appreciating anniversaries” edition

This is a weekly post we publish on Fridays with links to articles that touch on economic inequality and growth. The first section is a round-up of what Equitable Growth has published this week and the second is work we’re highlighting from elsewhere. We won’t be the first to share these articles, but we hope by taking a look back at the whole week, we can put them in context.

Equitable Growth round-up

There’s been quite a bit of theorizing that higher levels of inequality may cause lower levels of economic mobility. Up until now, there hasn’t been much evidence of a causal relationship. But a new paper finds a connection between higher levels of income inequality and higher high school dropout rates.

The effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policy in responding to the Great Recession has been one of the great economic debates of the past few years. But those debates overlook federal credit programs, which may have had a significant impact in countering the recession.

Earlier this week, Equitable Growth hosted economists David Card and Alan Krueger to discuss the impact of their book “Myth and Measurement” on our understanding of the minimum wage. In the 20 years since the book was published, the economics profession has changed its tune when it comes to the minimum wage.

Speaking of challenging the conventional wisdom, a new paper by Julien Lafortune and Jesse Rothstein of the University of California, Berkeley and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach of Northwestern University argues that school finance reforms can boost student achievement. Their brief for Equitable Growth dives into their results.

Bridget Ansel takes their results and argues that our current education policy debate could be improved by considering these findings. “Rather than ‘throwing money at the problem,’” she writes, “no-strings-attached funds may actually make a difference for the country’s most disadvantaged school districts.”

Links from around the web

If you listen to the hype about technology companies, you’ll probably hear the word “disruption” quite often. New tech companies, in this telling, will upend old established companies. But Noah Smith floats the possibility that technology could help facilitate market concentration. [bloomberg view]

Since the end of the Great Recession, wage growth and productivity growth have been quite weak in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Are wages low because of low productivity? Or is productivity low because of low wages? Ryan Avent says yes. [the economist]

As I mentioned above, Equitable Growth hosted David Card earlier this week—an economist who has made a number of important contributions to the field of labor economics. Peter J. Walker profiles this “challenger” of conventional wisdom. [imf]

The U.S. labor force participation rate, after years of declining in the wake of the Great Recession, has ticked up in recent months. Whether or not this trend will continue is uncertain, but what’s behind this movement? Ernie Tedeschi digs into the numbers. [medium]

Free-floating fiat currencies are supposed to help countries avoid financial crises provoked by borrowing too much from abroad. But that really only works when a country’s currency is widely accepted by its trading partners. Otherwise, old problems can still arise according to Frances Coppola. [coppola comment]

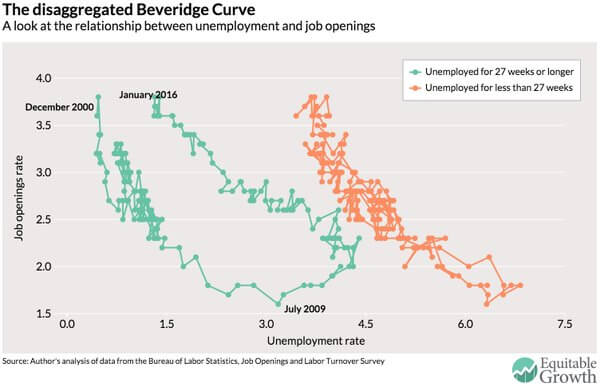

Friday figure

Figure created by Nick Bunker

Must-reads: March 18, 2016

Must-read: Martin Sandbu: “Manufacturing didn’t leave; it left workers behind”

Must-Read: : Manufacturing didn’t leave; it left workers behind: “America’s blue-collar aristocracy fell on hard times long ago…

…but its ghost remains influential in politics. That much is clear from Hillary Clinton’s vow to ‘bring manufacturing back’ and Donald Trump’s railing against the ‘mortal threat to American manufacturing’ (presumably any number of foreign countries with which the US trades, but in this case the target was the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement). One problem with this rhetoric, politically potent though it may be, is that manufacturing has never left the US. As the chart below shows, manufacturing output has grown at a steady pace for decades, only temporarily thrown off course by recessions before returning to its previous trend. American factories today produce as much as they ever have.

Of course the number of jobs in manufacturing has fallen deeply — US manufacturing employment peaked in the 1970s — with particularly steep slides in the recessions of the 2000s. And this is what drives the rhetoric, and makes the Trans-Pacific Partnership a particularly delicate issue, in the current US political campaign. Mark Muro and Siddharth Kulkarni are quite right to refer to the blue line above as a one-chart explanation of why voters are angry. That’s understandable even though, as Jeffrey Rothfeder points out, job numbers in US manufacturing have been on a steady increase since 2010. However, the fact that output has kept going up while employment has sunk like a stone means that the political narrative of manufacturing activity ‘stolen’, or whisked away to other countries, doesn’t quite add up. What the numbers show is, by definition, that manufacturing has become more productive as well as increasing in total output. In other words, what has been happening — since the 1970s — is a productivity-boosting restructuring, not a shrinkage…