Black economists are missing from the Federal Reserve and the U.S. economics profession

More than 40 years ago, Congress made the Federal Reserve responsible for fighting racial discrimination in the U.S. economy. The Fed’s maximum employment mandate arose directly from the civil rights movement, and the Community Reinvestment Act was a response to discriminatory practices at banks.

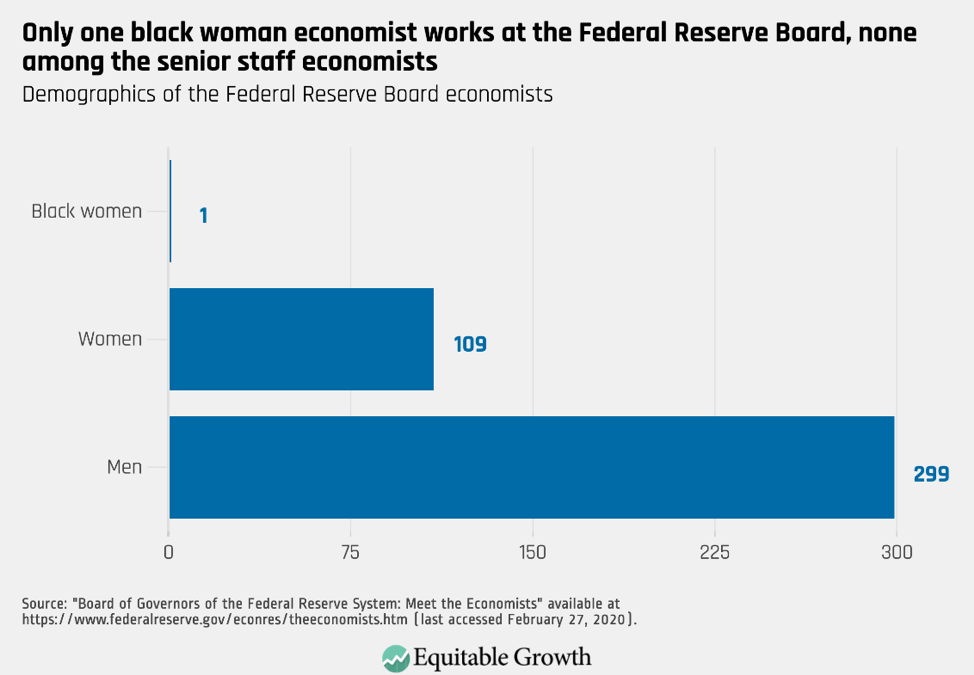

So, of course, the Fed would extend a similar mandate and responsibility in hiring its staff economists, including people of color, and encouraging them to work hard on those important responsibilities, right? Wrong. Among the 408 economists at the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, only one is a black woman. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1

Few other women of color or minority men work for the Federal Reserve Board. Moreover, only a small fraction of the staff’s research and economic analysis focus on race. People of any background could study race, yet in real life, our lived experiences often guide the questions we ask. Economists are no different.

Economists of color missing from the Fed means that race has largely been missing from its policy deliberations. Narayana Kocherlakota, the former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, pointed out that Fed actions have outsized effects on racial minorities. In the Great Recession, the black unemployment rate climbed to more than 16 percent. Any conversation at the Fed about full employment should have include the hardest-hit groups. It did not.

Today, the Federal Reserve is finally talking some about race—both in its evaluation of the economy and among its ranks. The Board has started many efforts to make its staff more diverse and its work environment more inclusive. But is the answer simply to hire more economists who are people of color? Wrong, again. Black economists are not only missing from the Fed, but also from the entire U.S. economics profession.

In 2017, only seven black women received a Ph.D. in economics in the United States. One year later, it was only four. Those abysmal numbers are out of the more than 1,000 individuals who receive a doctoral degree in economics each year. The Fed only hires its economists with doctoral degrees.

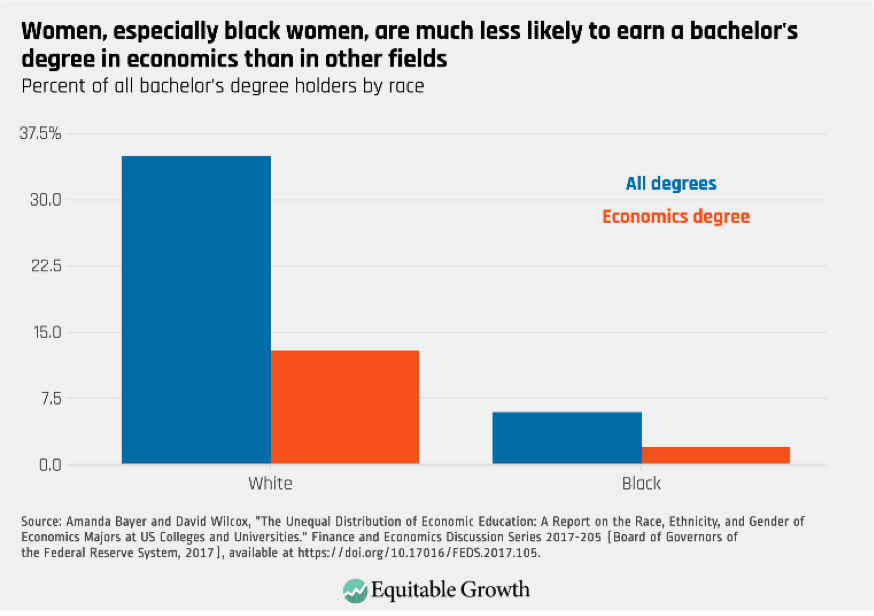

To make matters worse, the low numbers of black women in economics also occur at the undergraduate level. White women comprise 35 percent of all bachelor’s degrees, but only 13 percent of bachelor’s degrees in economics. Only 2 percent of economics undergrad degrees go to black women. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2

We need diverse viewpoints among economists, but the pipeline of talent is broken—yet not beyond repair. Since 2017, the economics profession in the United States has had a long-overdue awakening about gender and race. The leadership of the American Economics Association now recognizes the problem and is taking steps to combat discrimination and harassment. Even so, it is individuals who are up and coming in the economics profession from underrepresented groups who are demanding change and making it happen.

Last week, the Sadie Collective held its second annual conference for young black women interested in economics. Black women, from high school students to recent Ph.D.s, gathered to share their research, support each other, and learn from women who blazed a trail in the profession. They heard from Bridget Terry Long, the first black woman dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Susan Collins, the acting provost at the University of Michigan, and many other black woman economists.

I was spellbound to sit in the room with more than 270 young black women interested in economics. The energy, ambition, and talent were striking and heartening. These women have a strong voice, and it is a voice that economics and the Federal Reserve need to hear.

Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen also spoke to these black women. She underscored that diversity is crucial for the quality of economics and the quality of policy advice. She promised, as the current president of the American Economics Association, to push forward to make the profession better. The leaders of the Sadie Collective standing with her was a joy to witness.

In 1921, Sadie Tanner Mosell Alexander was the first African-American to receive a Ph.D. in economics and is the namesake of the Sadie Collective. After Alexander received her Ph.D., discrimination stood in the way of her economics career. Undaunted, she received a J.D. and went on to practice law. Alexander’s legacy ties back the Federal Reserve as well. She spoke extensively about the moral and economic case for full employment. The young black women at the Sadie Collective are honoring and carrying forward her work.